Ithra Exhibit Explains Hijrah's Importance in World History

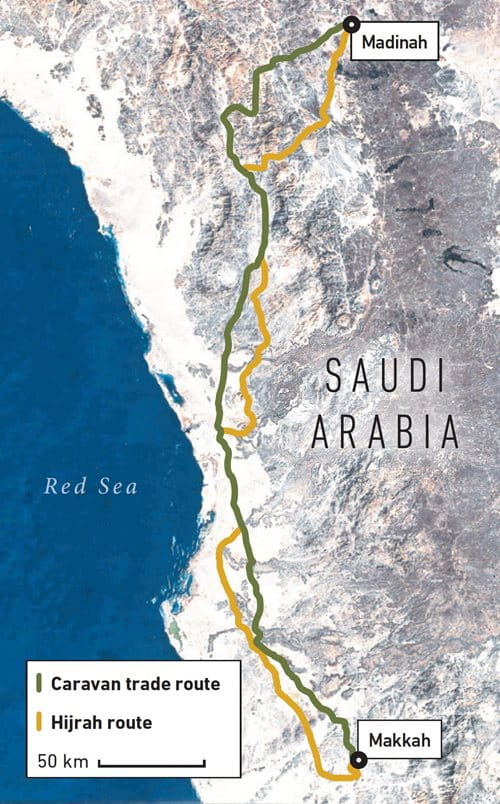

Avoiding main roads due to threats to his life, in 622 CE the Prophet Muhammad and his followers escaped north from Makkah to Madinah by riding through the rugged western Arabian Peninsula along path whose precise contours have been traced only recently. Known as the Hijrah, or migration, their eight-day journey became the beginning of the Islamic calendar, and this spring, the exhibition "Hijrah: In the Footsteps of the Prophet," at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, explored the journey itself and its memories-as-story to expand understandings of what the Hijrah has meant both for Muslims and the rest of a the world. "This is a story that addresses universal human themes," says co-curator Idries Trevathan.

10 min

Written by Peter Harrigan Photographs courtesy of Ithra

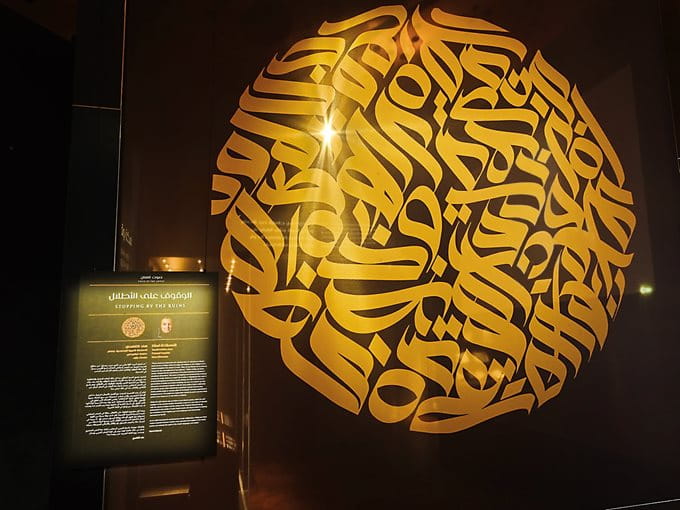

Qifa.

(Stop.)

The word appears in flowing strokes of gold Arabic verse arranged in a circle on black fabric four meters square by contemporary artist Hind Alghamdi. Despite the liquid complexity of her calligraphy, the piece feels spare, even meditative. Idries Trevathan, Ph.D., curator of Islamic art at the Ithra Museum in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, admits it is an incongruous word to hang at the entrance of an exhibition about a journey. All the moreso when the journey is one as epochal as this: the Hijrah of the Prophet Muhammad 1401 years ago from Makkah to Madinah in what is now western Saudi Arabia.

While this emphasizes the Hijrah as a bridge from pre-Islamic Arabia, the word works also to invite those not familiar with the tradition to pause to consider the relevance of the Hijrah to the wider world. Ithra Director Abdullah Al Rashid notes that the Ithra exhibition, “Hijrah: In the Footsteps of the Prophet,” is comprised of 14 zones spread over 1,500 square meters with installations, calligraphy, artifacts, manuscripts, cinematic productions, photography and even song assembled to bridge space, time and cultures.

“As befits the Hijrah’s significance in world history,” he says, the exhibit is “one of the most detailed studies ever of the history and topography of the journey.” Taking advantage of new studies and research, he adds, “we have deliberately taken a cross-disciplinary approach which looks at the history and legacy of the event from different perspectives, including science, history, theology, [and even] art and cultural memory.”

To artist Alghamdi, the first verse of the qasida is more than historical. It also evokes themes that today are finding new life with Arab creatives across media, she says. “As an artist interested in contemporary Arabic calligraphy, writing out these verses is special because I believe they represent the height of Arabic poetry and embody the spirit of the Arabic language even today,” says Alghamdi.

“Most Muslims know about the Prophet’s migration from Makkah to Madinah in a religious context, but few know about the journey of eight days that marked the beginning of the Islamic calendar and reshaped the Arabian Peninsula socially and politically,” says Laila Alfaddagh, director of the National Museum in Riyadh, which will host the exhibition later this year.

“This is a story that addresses universal human themes of courage, duty, loss, companionship, persecution, migration, community and freedom.”

—Idries Trevathan

The Arabic word hijrah translates in English best as migration or departure. Last year marked the 1,400-year anniversary of what was, in the moment, an uncertain, clandestine and potentially fatal flight of the 53-year-old Prophet Muhammad from his birthplace in Makkah north to the oasis town then known as Yathrib (now Madinah). It is one of the world’s great quest stories, standing among those of others such as Gilgamesh, Noah, Odysseus, Abraham, Moses, Buddha and Jesus.

In 638 CE, Muhammad’s second successor as head of the community of Muslims, Umar Ibn al-Khattab al-Faruq, considered the Hijrah so important that he established it as the inaugural moment of the Islamic, or Hijri, calendar.

Much about the Hijrah is considered well-documented, handed down through hadith (words and deeds of the Prophet as recounted by his companions) as well as early biographical accounts known as Sirah. We know the background story, some of the episodes that occurred along the way and what ensued after his welcome in Yathrib, which was soon renamed Madinah as the first city to be identified as Islamic. But there has, says Al Rashid, “always been substantial debate about parts of the route, as well as certain aspects of tradition which seemed difficult to square with the facts on the ground.”

Some of these gaps have now been filled by the exhibition’s research. “We have collected, salvaged and created new accounts in cooperation with more than 70 researchers and artists from over 20 countries,” says Trevathan. For example, he points out that one of the exhibit’s centerpieces is a contemporary tent of goat and camel hair woven by Amazigh artisans in Morocco to represent the tent of Umm Ma’bad, the site of a crucial encounter on the second day of the Hijrah. Similarly, he adds, the museum worked with artists and artisans from more than a dozen countries and sought guidance from half a dozen universities and institutions.

Trevathan reflects on the challenge of how to present the Hijrah in a way that went beyond the literal, canonical or prosaic and extended to the archetypal and experiential. That was where contemporary art came in: “Some of the spirit of the journey is best captured and expressed by way of the poetry, art and culture of what people have created of the story,” he says.

Entering the exhibition, past Alghamdi’s calligraphy, the visitor walks into an interpretation of the city of Makkah during the half century of Muhammad’s life leading up to the Hijrah in 622 CE. Here artifacts associated with the city’s rituals and practices point to the polytheism that prevailed there alongside the presence of monotheistic Jews and Christians as well as the small but growing number of Muslims. On loan from the National Museum are clay and stone findings from archeological excavations at sites in the western Arabian Peninsula such as Qaryat al-Faw, Mada’in Salih, Tayma and al-Rabadhah that include statues, anthropomorphic stelae and altars for offerings and sacrifice. An incense burner with astral symbols and a clay figurine of a camel carrying jars are also typical artifacts that reflect the time.

The exhibition’s co-curator, Kumail Almusaly, Ph.D., who is responsible for traveling exhibitions at Ithra, observes that in those times, life in Makkah was mostly “harsh, unjust and dictated by reckless and extreme behavior.” The powerful mercantile Quraysh tribe dominated the city and “capitalized on Makkah’s ancient reputation as a place of pilgrimage by encouraging visiting tribes to use the Ka’aba as a shrine for their idols, thus turning the city into a center of both trade and idol worship.” Muhammad sought to end such practices and turn Arabia to a monotheistic path.

The Hijrah was a journey that “represents an isthmus separating two historical worlds.”

—Ashraf Faqih

As Muslims in Makkah increased in number, the Quraysh began subjecting the Prophet and his followers to “social isolation, economic boycotts, persecution and torture,” says Almusaly. Some had already migrated across the Red Sea to Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). The Quraysh feared that if Muhammad left Makkah, he could set up a new rival base elsewhere, most likely in Yathrib.

Pressed to resolve this threat, the Quraysh nobles gathered in the Dar al-Nadwa (town hall) and agreed on an assassination plot. The exhibition screens a two-part cinematic reconstruction of this plan, which involved the recruitment of a dozen assassins from various clans and tribes in order to spread the responsibility. But the attempt failed, and it led the Prophet to risk an escape from Makkah that became the first steps of the eight-day Hijrah.

Professor Abdullah Alkadi has spent four decades in field studies, research and study of the Prophet’s journey. He is the first researcher to personally walk its entire length, collecting data, identifying landmarks and looking to literature, historic documents, folk memories as well as geospatial technologies to fill out the story of the precise route and locations of events along the way. His research proved crucial to the accuracy of the Hijrah story from this point on.

After the attempted assassination, Almusaly says, Muhammad left Makkah in secret together with his close friend Abu Bakr al-Siddiq, who later became the first caliph, or successor as head of the Muslim polity. Reckoning their persecutors would assume they were heading north to Yathrib, the pair instead headed south and hid for three days in a cave on the peak of Mount Thawr.

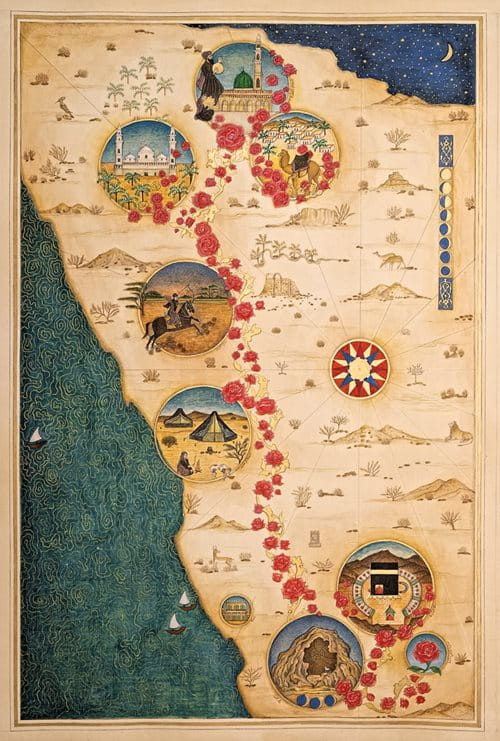

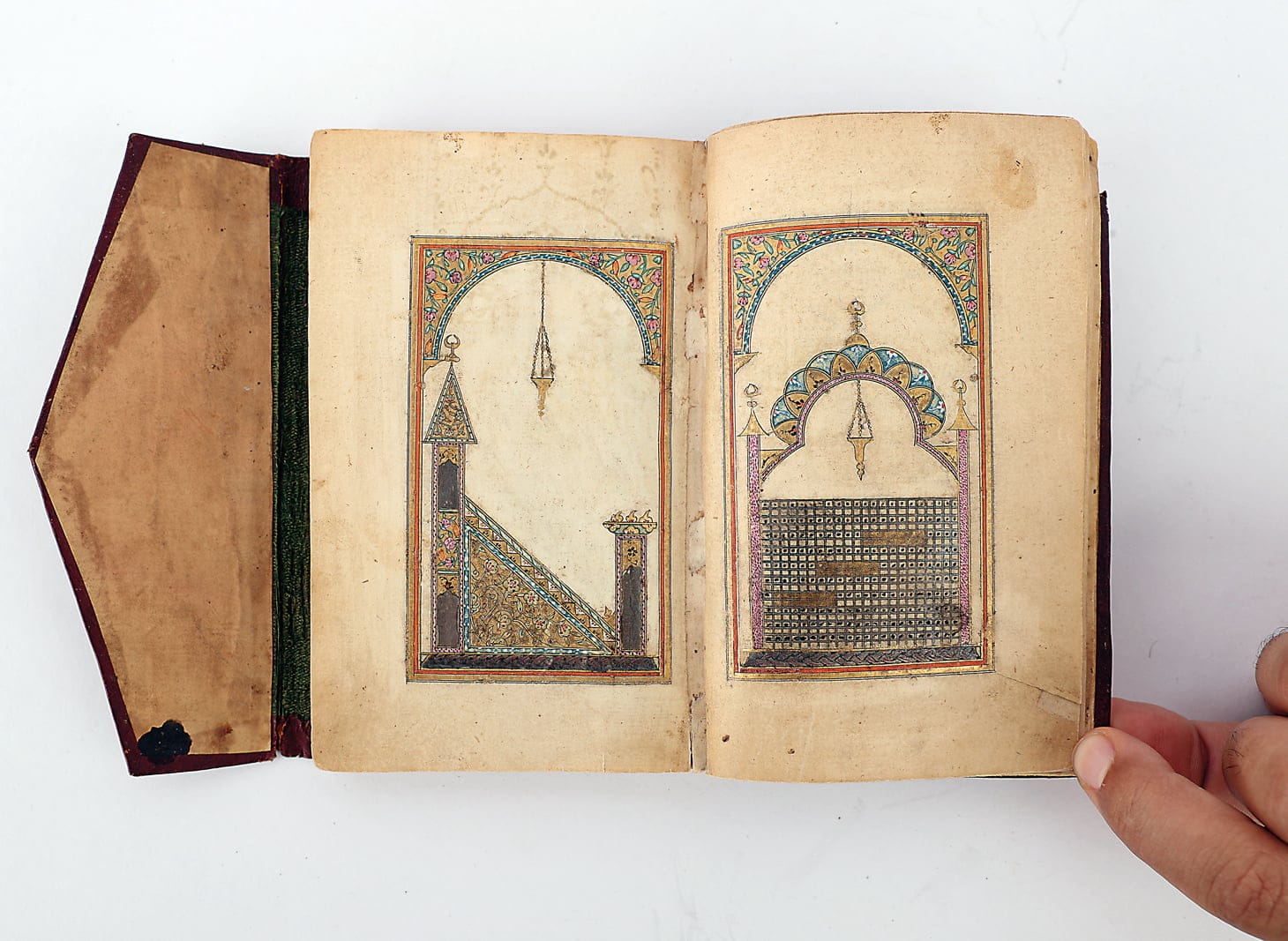

Artist Ayesha Amjad’s neotraditional “Hijrah Memory Map” right depicts the route of the Hijrah using roses, a symbol used for centuries in connection with the Prophet Muhammad. Left, this simple design, produced in 1901 in Morocco, represents one of the Prophet’s sandals, and it would have been carried by its owner as a symbol of protection.

After narrowly avoiding capture there, they set off west toward the Red Sea coast. Then, led by their guide Abdullah bin Urayqit, they turned north. “It’s important to remember that they did not use the main route between the two cities,” says Almusaly. “They took trails that meandered between mountains and along secluded valleys” in order to avoid being spotted.

Each day of the Hijrah is given a zone in the exhibition, each one incorporating large-scale panoramic projections of the territory they traversed: Most of it is rocky, rugged, shadeless and scant of water. The landscape films, along with three dramatic reconstructions and four mini-documentary films, are all by award-winning film director Ovidio Salazar. In the exhibition, he says, they can “act as aids to contemplation for those willing to give more than a cursory glance.”

“Some of the spirit of the journey is best captured and expressed by way of the poetry, art and culture of what people have created of the story.”

—Idries Trevathan

Important to the story of the Hijrah are Salazar’s landscapes. The film crew, he says, “literally followed in the Prophet’s footsteps, trying to imagine the journey he undertook 1,400 years ago and the circumstances surrounding it.” This included shots using near-infrared filtration to evoke the light of the waxing moon that lent itself to an enduring nasheed (Islamic song) marking the Prophet’s eventual arrival in Madinah, “tala’a al-badru ‘alayna” (“The Full Moon Rose over Us”). This nasheed has become so celebrated and ubiquitous that there are few Muslims who cannot sing its lines, and it is a testament to the Hijrah story’s endurance over generations. Legendary Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum recorded the most famous version in 1966, and 10 years later it was used as the score in the film The Message. Yusuf Islam (formerly Cat Stevens) sang it in 1995, and in 2015, 300 schoolchildren in Ottawa sang a version to welcome refugees fleeing war in Syria. In the “Hijrah” exhibition, visitors can use headsets to listen to eight versions.

The exhibition’s silent projections use 15 screens to emphasize aerial sequences that range over the daunting landscapes, each screen nearly the size of those in commercial cinemas. To Salazar, these “encourage the viewer to participate in the narrative on its own terms,” evoking not just the beauty of the terrain “but allowing the mind to wander, contemplating what the experience of the migration might have entailed.”

The projections also help amplify the theme evoked by Alghamdi’s calligraphic installation, known generically as atlal, the ruins motif. Trevathan explains that this expresses a larger and more complex vision of how pre-modern Muslims imagined and engaged with land by “embracing notions of melancholy, desolation, loss, sorrow and seeing in the landscape a reminder of a longed-for past.” This makes the atlal motif “both empty and replete,” says Trevathan, or, as it was described by American scholar of myth Joseph Campbell in his 1949 classic The Hero with a Thousand Faces, “an unadorned vacuum into which the imagination of the beholder can pour.”

In its reappropriation of the atlal, says Trevathan, the exhibit aims to connect the role of memory as a device for structuring the experience of the Hijrah-as-story through landscape. “Nowhere is this remembering more powerfully invoked, and the memory of Prophet Muhammad more strongly bound up with natural landscape, than along the Hijrah migration route. The story of this journey has a special place in the collective memory of the Muslim world and connects a sacred landscape with one of the most significant episodes of the Prophet’s life and a foundational narrative in Islam.”

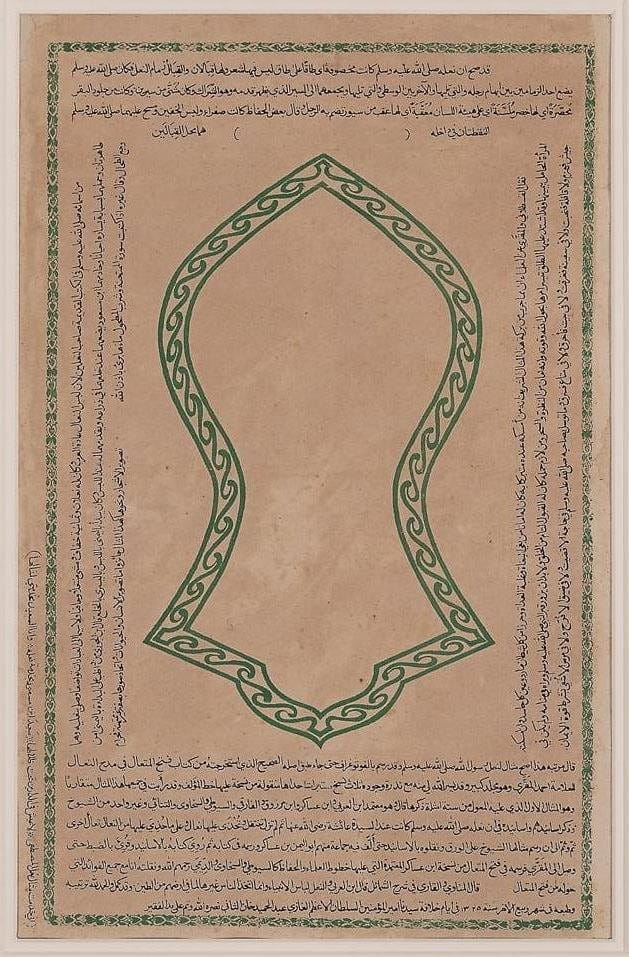

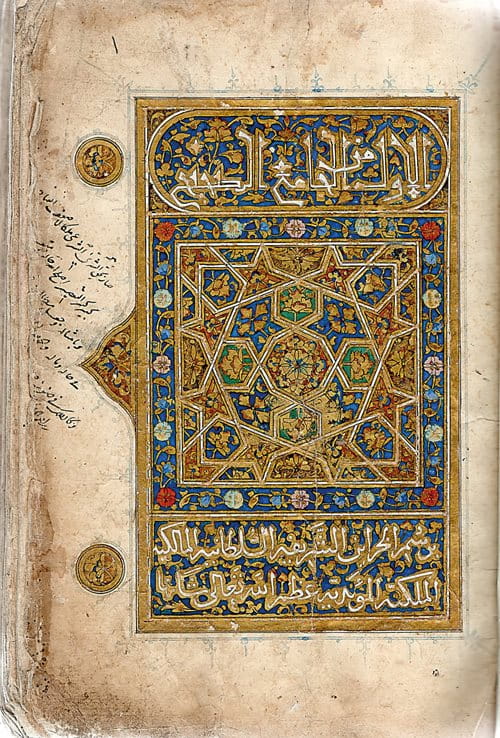

Trevathan stresses that as well as remembering and celebrating the landscapes of the Hijrah, the exhibition remains anchored by collections, works of artists, master artisans, poets and sound recordings as well as historical objects. One particularly intriguing example is the calligraphic art form of hilye. Since figurative representations of the Prophet remain prohibited in Islam, portrait-by-narrative—hilye—described the Prophet’s appearance and personality in ornately written and illuminated panels.

One of the most famous descriptions arose from the second day of the Hijrah, when the travellers stopped at the tent of a Bedouin family where a woman, Umm Ma’bad, offered hospitality. The description of the Prophet attributed to her is considered among the most eloquent and detailed that exist.

Inside the recreated goat- and camel-hair tent stands a stylized, cinematic triptych depicting Umm Ma’bad, played by actor Ghadeer Yamani, looking into the camera while a narrator recites her description as another panel shows film of the remnants of a desert encampment—a reference again to the atlal—and the third panel depicts calligrapher Nuria Garcia Masip creating a hilye with Umm Ma’bad’s words.

Almusaly notes that there was another portentous, now-famous incident on that same day, which is also represented prominently in the exhibit. According to the account of 14th-century scholar and historian Ibn Kathir, soon after leaving Umm Ma’bad’s tent, the travellers spotted a lone horseman bearing down on them: the bounty hunter Suraqah al-Kinani. Motivated by an offer from the Quraysh of 100 camels to capture or kill Muhammad, he tracked them down. But as he approached, his horse fell and then sank in the sand. He became frightened and, impressed that Muhammad was being protected by divine force, vowed no harm and rode off: Salazar turned the encounter into a short film styled along the lines of American Westerns.

After eight days the mujahirin (migrants) neared the oasis of Yathrib and the fields of sharp black lava and volcanic cones surrounding the city. Their arrival marked the founding of Islam’s second holy sanctuary after Makkah and the first city that entirely identified with Islam. Subsequently renamed Madinah with its epithet al-Munawarah, the Radiant, it also took the name of Dar al-Hijrah, or Abode of Emigration.

Accounts about this moment recorded from al-Bara’ bin ‘Azib tell how those people of Yathrib who welcomed and sheltered the Prophet and his followers, and were already Muslims or later embraced Islam, became known as ansar, the helpers. Ultimately it is the unity between muhajirin and ansar that is the defining feature of the Hijrah story, and it has contributed to the ethical principles relating to the treatment and protection of foreign and migrant communities ever since. The epic journey formed a historical rift between the time before the flight and the time after. Ashraf Faqih, former programs manager for Ithra and a popular author of contemporary science fiction and historical fiction, writes that the Hijrah was a journey that “represents an isthmus separating two historical worlds that are distinct and different in character, discourse and the language of obligation.” For these reasons he adds “the Hijrah has rightfully cemented itself as a pivotal moment.”

Speaking to the role of the ansar, eighth-century historian and biographer Ibn Ishaq of Madinah recorded that, eager to host the Prophet in their homes, some of the ansar tried to lead his camel, named Al-Qaswah. Reluctant to show favor to one person or another, the Prophet asked that Al-Qaswah be left to wander to choose a place to rest. She stopped and knelt at a place for drying dates, and there, Muhammad and his fellow muhajirin joined the ansar to use mud brick, palm wood and fronds to build a small structure: the Prophet’s mosque.

With that, the Hijrah was complete, an event in history that became one of the world’s most influential stories of revelation, separation, trial, refuge and transformation.

You may also be interested in...

AramcoWorld: 75 Years of Visual Storytelling Through Photography

Arts

History

Part 2 of our series celebrating AramcoWorld’s 75th anniversary this year highlights “visual vagabonding”—the magazine’s expanded use of vibrant images over the decades to fulfill the mission of cultural connection.

Ramadan Picnic Photograph by Zoshia Minto

Arts

On a warm June evening, people gathered at a park in Bethesda, Maryland, for a community potluck dinner welcoming the start of Ramadan.

"Duet": Senegalese Double Portrait

Arts

“Duet” comes from the Latin root word duo which means two. The Duet series focuses on double portraits, a tradition in West Africa.