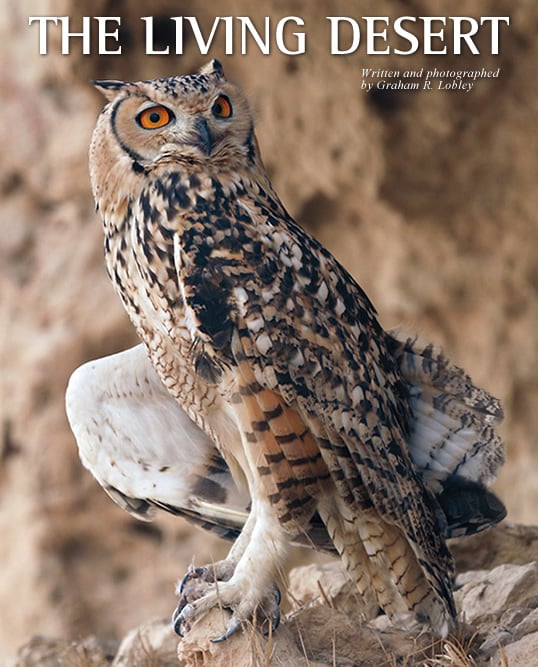

Pharaoh eagle owl

This large, impressive owl reveals beautifully marked plumage when viewed close-up. Recently recognized as a full species and named Bubo ascalaphus, it is a well-known desert creature, even figuring on the stamps of Yemen and some other countries. These owls are normally found in remote, rocky areas, where they feed primarily on small rodents and are sometimes active into the early morning. Their flight is completely silent, so they are the ultimate stealth raptors. They have also adapted to living in close quarters with humans. For example, eagle owls on the outskirts of Hurghada, Egypt, on the northwest coast of the Red Sea, have become opportunistic feeders, eating urban rodents such as rats and mice. |

But a closer look reveals an intriguing range of hardy plants, animals and insects, each with specialized strategies for surviving an extremely arid climate. The stark beauty of the desert landscape and the remarkable resilience of its wildlife characterize an environment that is both extremely challenging and exciting.

|

Eastern imperial eagle

The eastern imperial eagle (Aquila heliaca) is a large, majestic bird with a wingspan of up to 2.1 meters (6'10"). Considered globally vulnerable, its estimated population is around 15,000 worldwide. It is a regular winter visitor across the Peninsula, albeit in relatively low numbers—perhaps 500 to 1000 birds. These eagles mature in six to seven years, and this bird is a juvenile, less than a year old. In Saudi Arabia, adults and subadults (birds four to five years old) are found along with younger birds, but youngsters predominate farther south in Oman, indicating that adults stay closer to their breeding ranges in Eurasia. Adults sport a distinctive golden-yellow crown and nape that recalls the golden eagle, hence the specific name heliaca, from the Greek heliakos, meaning “of the sun.” |

|

Hoopoe

The hoopoe (Upupa epops) is unmistakable. It has distinctive pinkish-brown plumage with black and white wings. It raises its long crest momentarily when excited or alarmed. In 1998, I confirmed the hoopoe as an addition to the breeding avifauna of Dhahran, where it nests under the eaves of homes and in holes in the limestone hills. In the Mediterranean, nest sites include holes in old olive trees and even stone walls. In Dhahran, it is easy to observe when it is feeding on lawns and sandy patches, where it uses its long curved bill to probe for bugs and grubs, often tossing the latter into the air before swallowing them. |

A desert can be defined as a region that receives less than 25 cm (10") of rainfall a year. The amount of precipitation in most of Saudi Arabia falls below this figure, although violent rainstorms—such as the one that struck Jiddah, in the Hijaz area of western Saudi Arabia, last November—can cause severe flooding. In the east, the region with which I am most familiar, annual rainfall averages under 10 cm (4"), but can occasionally be double that. In the vast sand sea of the Rub’ al-Khali, or Empty Quarter, in the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula, rain may not fall for years. In the summer, temperatures there and elsewhere can climb to 50 degrees Celsius (122°F).

Consequently, many desert animals are nocturnal, with breeding cycles that culminate during the cooler spring months. Resident birds have wider ranges than many of their counterparts in more clement environments. Although some are nocturnal or crepuscular—active at dusk—many are also nomadic, moving to locations where erratic rains have promoted vegetation. One year, the beautiful cream-colored courser nests in an area with suitable vegetation in eastern Saudi Arabia, but is completely absent the next, when conditions are better elsewhere.

Plants form the first link in the desert ecosystem and food chain. Seeds of the annuals germinate after spring rains, producing an ephemeral greening of the desert. Seed germination is often triggered after several showers rather than just one, increasing the chances of successful growth, although a single soaking rain can have the same result. This vegetation, including unusual plants like the parasitic desert hyacinth, or desert candle, nurtures and shelters insects. These, in turn, provide sustenance for other creatures, such as birds.

|

Rüppell’s sand fox

This elegant little fox (Vulpes ruepelli) has large ears and a bushy tail, and is mainly nocturnal. Its short fur and large ears may keep it cool, helping it survive in high temperatures. Several foxes can emerge from a single den near dusk and remain active until after sunrise. The sand fox’s diet consists mainly of small mammals, lizards and insects, but it can also take birds up to the size of doves. It is distributed sparingly across the deserts of North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula and east into Afghanistan. |

|

Spiny-tailed lizard

The spiny-tailed lizard (Uromastix microlepsis) is a large, impressive reptile fairly common in the eastern scrub desert of Saudi Arabia, especially in its northern reaches, up to and including the Dibdibah alluvial plains near Hafr al-Batin. Called dhub in Arabic, it is gray when cold, but turns beige-yellow basking by its hole in the morning sun. This lizard is mainly a vegetarian and may go its whole life without drinking, instead taking moisture from what it eats. Although agile and fast—it can run at speeds exceeding 25 kilometers per hour (15 mph)—it is definitely on the menu of raptors such as buzzards and even eagles, and is also a Bedouin dish. It uses its underground burrow, up to three meters (10') long and 1.5 meters deep, as a refuge from both the midday heat and predators. |

|

Blue-throated agamid

Agamid lizards are thought to be related to iguanas. Dominant males can turn their throats bright blue and tails orange. These striking creatures warm up on rocks or outcrops early in the morning. They eat mainly insects. |

Among the most visible insects are butterflies like the painted lady, a migrant, and the desert white, a full-time resident. The striped hawkmoth is another remarkable winged migrant. In wetter years, large numbers of these moths migrate north in spring, and their colorful caterpillars are soon feasting on the desert vegetation, including on Rumex, a sorrel. Successive generations of hawkmoth may range as far north as Scandinavia in a good breeding season.

But the best-known migrants, of course, are birds. Indeed, the spectacle of birds crossing the Peninsula every spring and fall has captured the imagination of humankind since ancient times. As many as three billion birds of more than 200 different species transit annually, traveling between their African winter quarters and their breeding ranges in Europe and western Asia, and a number stop in the eastern Gulf region to rest and refuel before continuing their long journeys. The stunning, harlequin-colored bee-eaters are among the most vividly feathered of these temporary visitors.

The hoopoe, with its jaunty crest, is a typical migrant across the Arabian Peninsula, although there is a resident population in the more temperate Hijaz mountain region. Called hudhud in Arabic, this iconic bird is mentioned in the Qur’an as a messenger of the prophet Suleyman (King Solomon). Its principal breeding range is around the Mediterranean, extending into Turkey, Iraq and Iran. Remarkably, since 1998 it has also become a regular breeding bird in Dhahran, Saudi Aramco’s headquarters town near the kingdom’s east coast, reflecting the increasingly attractive habitat formed by this well-vegetated, man-made oasis.

|

Carmine darter dragonfly

The striking carmine darter dragonfly (Crocothemis erythraea) is the most widespread in the Arabian Peninsula. The male is a handsome carmine red, while the female is a significantly drabber yellow-buff color. It prefers a habitat of rocky wadis (normally dry watercourses) and desert pools, especially in western Saudi Arabia. It avoids true oases, where it is replaced by the closely similar scarlet darter (Crocothemis chaldaeorum) in the east, at al-Hasa and Qatif. This photo was taken in late afternoon at a patch of vegetation that had attracted many dragonflies and butterflies. |

To cope with torrid summer temperatures, some perennial plants become dormant in a process called estivation. However, a few, such as Calotropis procera (giant milkweed) and Ochradenus, an important food plant for the desert white butterfly, even flower during summer, providing vital continuity for insects over the hot season. Small mammals like the gerbil, jird and jerboa retire into their burrows and survive on food stored in the spring. At the top of the food chain are predators, including owls, raptors and foxes. The large and impressive pharaoh eagle owl is a full-time resident, but several largely Asian eagle species winter in the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula.

|

|

|

|

|

Striped hawkmoth caterpillar

The striped hawkmoth (Hyles livornica) is common in the desert, where the nectar of blue Lycium flowers is the adult’s preferred food. In wetter years, it breeds rapidly, and its striking caterpillars can then be found everywhere feeding on sorrels and other favored plants. Noted for their mass northerly migrations, successive generations of hawkmoths may travel as far as Scandinavia in a good breeding season. |

|

Picris flowers

The 2006–2007 winter-spring season was relatively wet in eastern Saudi Arabia, so many different plants put on an excellent spring showing. These yellow Picris flowers were photographed with part of the Shedgum Escarpment in the background. Picris are common in eastern Saudi Arabia and sometimes form floral carpets on the Dibdibah gravel plains in the north around Hafr al-Batin. |

|

Desert hyacinth

Flowering in February, the widespread desert hyacinth (Cistanche tubulosa) adds a welcome splash of color to desert areas with its bright yellow spike of flowers. Called dhanun in Arabic and part of the broomrape family, this striking parasitic plant lacks chlorophyll and uses a long, threadlike root to tap nutrients from its host plant. It is an annual, and hundreds of tiny seeds are dispersed from an ovoid fruit capsule in the spring. This picture was taken on the seashore north of al-Khobar in eastern Saudi Arabia. |

During my 18 years working in Saudi Arabia, I became ever more fascinated by its deserts. The springtime flower displays that pop up almost overnight, and seem to disappear just as quickly, may be enjoyed by all, as can a variety of other typical desert wildlife shown here.

|

Graham R. Lobley is a metallurgical engineer, as well as an avid naturalist and wildlife photographer who has written extensively on the flora and fauna of Saudi Arabia. He retired from Saudi Aramco in January after an 18-year career in the kingdom and now works in London. |