early 13 years ago, under the heat of a summer sun, archeologists were working in a trench excavated in a mound on the outskirts of the ancient town of Thaj, in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. So far, they had unearthed only pottery fragments and ashes. Prospects seemed dim.

early 13 years ago, under the heat of a summer sun, archeologists were working in a trench excavated in a mound on the outskirts of the ancient town of Thaj, in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. So far, they had unearthed only pottery fragments and ashes. Prospects seemed dim.

Suddenly, a few more scrapes with the trowel opened a hole. Burrowing further, Abdulhameed Al-Hashash and his crew from the Dammam Museum uncovered a burial chamber. A few days later, they found the grave goods: a small mask, a glove, a belt and several necklaces—all of pure gold—as well as other exquisite jewelry that adorned the crumbled remains of what turned out to be a six-year-old girl buried nearly 2000 years ago.

Delicately crafted in repoussé to show a tight mouth, long nose and slitted eyes, the “Thaj mask” is reminiscent of the so-called Mask of Agamemnon, discovered in 1876 at the second millennium bce site of Mycenae. The Thaj mask and its companion objects are just a few of the remarkable displays in the exhibition “Roads of Arabia,” which showed at the Louvre in Paris from July to September of last year.

What is perhaps most remarkable of all, however, is that “Roads of Arabia: Archaeology and History of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia” is the first-ever comprehensive international exhibition of Saudi Arabia’s historical artifacts. With 320 objects ambitiously spanning more than a million years, from the Paleolithic to the 1932 birth of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, it turns out to be a veritable parade of virtually unknown treasures, each one a fragment of a tale from the civilizations that, over millennia, interwove their arts and their trade far more extensively than even scholars had previously believed.

|

| héléne david / musée du louvre |

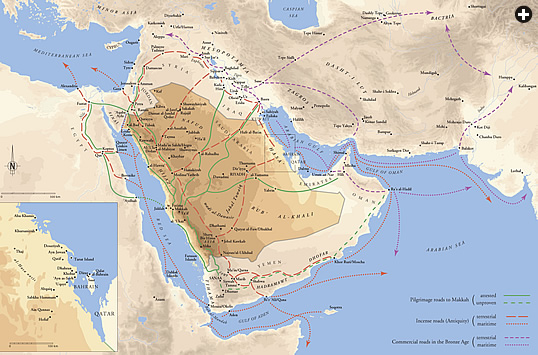

his historic assemblage, which was exhibited in Barcelona through February and will visit St. Petersburg, Berlin and Chicago through 2013, situates the Arabian Peninsula not on the periphery of the ancient world, but squarely within a far-reaching network of trade and pilgrimage routes linking India and China to the Mediterranean and Egypt, Yemen and East Africa to Syria, Iran and Mesopotamia. It makes clear that while absorbing influences from surrounding empires and kingdoms, the early Arabians crafted their own, often regionally distinctive, ceramics, jewelry, painting and sculpture.

his historic assemblage, which was exhibited in Barcelona through February and will visit St. Petersburg, Berlin and Chicago through 2013, situates the Arabian Peninsula not on the periphery of the ancient world, but squarely within a far-reaching network of trade and pilgrimage routes linking India and China to the Mediterranean and Egypt, Yemen and East Africa to Syria, Iran and Mesopotamia. It makes clear that while absorbing influences from surrounding empires and kingdoms, the early Arabians crafted their own, often regionally distinctive, ceramics, jewelry, painting and sculpture.

Beyond the Thaj gold, some of the most eye-catching and culturally significant works include a trio of male statues, each slightly larger than life-size, dating from the fourth to third centuries bce and representing monarchs from the little-known north Arabian kingdom of Lihyan. There are also remarkably well-preserved wall paintings, luminous alabaster heads and Hellenistic bronzes from Qaryat al-Faw at the edge of the Rub’ al-Khali (Empty Quarter). From eastern Arabia there are soapstone vessels found on Tarut Island that depict entwined snakes and figures. There are stone monuments with writing in Aramaic, South Arabian, North

Arabian and Arabic—the earliest known use of that language.

The most elegant writing appears near the exhibition’s end

and comes from Makkah, carved on an evocative series of tombstones that offer vignettes of the lives of individual pilgrims from all over the Muslim world between the ninth and 16th centuries ce.

Drawing principally from collections in the National Museum in Riyadh, “Roads” is supplemented with key pieces from the kingdom’s regional and university museums, libraries and foundations. There are also textiles from the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, ceramic plaques depicting Makkah and Madinah from the Louvre and 18th-century engravings of the Holy Cities from the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. A rarely seen map of the Hijaz railway, which was built by the Ottoman Turks in the early 20th century, is on loan from the Royal Geographic Society in London.

Critics have greeted the show with unabashed wonder. Writing in the Parisian daily Le Figaro, Eric Biétry-Rivierre marveled at the discovery of “a brilliant and prosperous past, almost completely unknown in our latitudes.” International Herald Tribune art critic Souren Melikian remarked that “the revelations to be found in hundreds

of artifacts never before seen outside Saudi Arabia are startling.”

Experts have been equally effusive. “It is fantastic to show the world what a wealth of archeological treasures exists in the kingdom,” commented Daniel Potts, professor of Middle Eastern archeology at the University of Sydney. He is one of more than three dozen scholars to contribute articles to the exhibition’s 600-page catalogue. “Saudi Arabia remains the least explored and obviously the largest piece of the puzzle that is ancient Arabia,” he continued. “This exhibition should do a great deal to encourage scholars to look more seriously at

the region.”

Experts have been equally effusive. “It is fantastic to show the world what a wealth of archeological treasures exists in the kingdom,” commented Daniel Potts, professor of Middle Eastern archeology at the University of Sydney. He is one of more than three dozen scholars to contribute articles to the exhibition’s 600-page catalogue. “Saudi Arabia remains the least explored and obviously the largest piece of the puzzle that is ancient Arabia,” he continued. “This exhibition should do a great deal to encourage scholars to look more seriously at

the region.”

he genesis of this museological coup dates back to April 2004, when the Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities (scta) signed a cooperation agreement with the Louvre. The first fruit of the exchange was the survey exhibition of 150 items entitled “Masterpieces from the Louvre’s Islamic Arts Collection” that opened in the Saudi National Museum in the spring of 2006. (In a separate venture, the Louvre is constructing, with multinational financing, its own new wing devoted to Islamic art, slated to open in 2012.)

he genesis of this museological coup dates back to April 2004, when the Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities (scta) signed a cooperation agreement with the Louvre. The first fruit of the exchange was the survey exhibition of 150 items entitled “Masterpieces from the Louvre’s Islamic Arts Collection” that opened in the Saudi National Museum in the spring of 2006. (In a separate venture, the Louvre is constructing, with multinational financing, its own new wing devoted to Islamic art, slated to open in 2012.)

Ali Al-Ghabban, vice president of antiquities and museums at the scta and co-curator of “Roads,” explains that the reciprocal show is “part of our long-term strategy to use antiquities to promote the country and build tourism. It will also help the Saudis to be proud of their heritage.”

The show’s catalogue, he continues, was published in French, English and Arabic. “It’s more than an exhibition catalogue,” contends Al-Ghabban. “It’s a scientific document that details how numerous civilizations have contributed to Saudi Arabia’s history.”

The affable archeologist, a professor at Riyadh’s King Saud University who earned his doctorate at the University of Aix-en-Provence, is a veteran of archeological surveys and key discoveries over more than three decades. He took time out from a day of meetings at the Louvre to be my guide through the show and later discuss it over a Moroccan fish couscous in the food court adjoining the museum.

“Most westerners believe that Saudi Arabia is only a desert land with oil wells,” he explained with an indulgent smile. “They don’t know that the country was a bridge between the East and the West. We played this role in the fourth millennium bce, and we continue to play it. In the outside world, we should correct the wrong image of our country. And within Saudi Arabia, too, we need to educate people about their heritage. We would like to show everyone—both foreigners and Saudis—how we have participated in the history of humanity, not only in the Islamic period, but even before Islam.”

At the Louvre, for Béatrice André-Salvini, co-curator of the show with Al-Ghabban and director of the Louvre’s Ancient Near East department, “Roads” has been “a highlight of my career,” she says. “The whole process of putting together the exhibition has been something very passionate for me.” With Al-Ghabban and others, she says, the curators sought to balance beauty to modern eyes with “pieces that demonstrate turning points.”

Because many westerners imagine the Peninsula as little more than endless sand, the exhibit emphasizes the diversity of Arabian geography with wall-sized black-and-white panoramas by Brazilian photographer Humberto da Silveira, who has spent years in the kingdom. “Before each section, we want visitors to understand that people live in oases and mountainous regions, and that there were important urban centers,” the curator observes. “We want to change perceptions of the country.”

Even though she is an expert, André-Salvini admits that she too was staggered by the variety and the wealth of the finds. “The history of Saudi Arabia is made from contact with surrounding civilizations,” she explains. “But in spite of these foreign influences, everything from outside was absorbed and reinterpreted in an unmistakably original fashion.”

Just how original becomes evident in the first gallery as the ancient meets modernity: Three sublime anthropomorphic sandstone grave markers look as if they might have been crafted by an abstract sculptor of the 20th century—yet they are more than 5000 years old. Among them, a diminutive torso with seemingly doleful eyes and a hand poignantly held over its heart stands out for its extraordinary expressiveness, achieved with a few sparely etched lines that adroitly captured the collarbone, hands and arms, quizzical mouth and odd, knob-like ears.

“I dubbed him 'the suffering man,’” André-Salvini recalls with a laugh, and the name stuck. The enigmatic character soon became a star of the show, singled out as the literal “poster boy” of the event to become a ubiquitous visual presence on banners inside the museum and on the front cover of the French edition of the catalogue.

Found near Ha’il in the north-central region of the country, the statue had been erected in an open-air sanctuary, according to André-Salvini. Based on similarities to other stelae excavated in Yemen with skeletal human remains carbon-dated between 3500 and 3100 bce, she concludes that the “suffering man” was produced in the same era.

By the middle of the third millennium bce—around 4500 years ago—as the Arabian Peninsula’s climate grew hotter and drier, trade emerged in the Gulf region. The exhibition showcases an abundance of objects from this period that were uncovered in 1966 on Tarut Island, on the Peninsula’s east coast, during the construction of the causeway that today links Tarut to the mainland. The hoard includes gray and black soapstone jars, bowls and fragments, many carved with snakes, leopard-like cats, lion-headed eagles and other mythic figures. In a catalogue essay, archeologist Potts contends that Tarut was the main port—and probably the capital—of the early Dilmun civilization, and that only later, around 2200 bce, did Dilmun move south and east to the island that is today Bahrain.

By the middle of the third millennium bce—around 4500 years ago—as the Arabian Peninsula’s climate grew hotter and drier, trade emerged in the Gulf region. The exhibition showcases an abundance of objects from this period that were uncovered in 1966 on Tarut Island, on the Peninsula’s east coast, during the construction of the causeway that today links Tarut to the mainland. The hoard includes gray and black soapstone jars, bowls and fragments, many carved with snakes, leopard-like cats, lion-headed eagles and other mythic figures. In a catalogue essay, archeologist Potts contends that Tarut was the main port—and probably the capital—of the early Dilmun civilization, and that only later, around 2200 bce, did Dilmun move south and east to the island that is today Bahrain.

Similar soapstone vessels, in what archeologists call the intercultural style, were widely traded from the Levant to Central Asia. They turn up in Syria, Mesopotamia, Iran and as far east as the Ferghana Valley in present-day Uzbekistan. Although Al-Ghabban believes that the show’s particular objects were fashioned on Tarut using local stone, other scholars, including Potts and André-Salvini, lean toward origins in southeastern Iran.

There’s no dispute, however, that the limestone statue of a man, who is probably shown praying, was sculpted on Tarut. With his clasped hands, round head, protuberant eyes and triple-belted waistband, he resembles Sumerian models from the same period around 2500 bce. But his squarish legs and knobby knees are similar to Indus Valley effigies, too. More curiously still, at nearly a meter (39") tall, he is the largest Mesopotamian-style statue discovered to date, notes André-Salvini—considerably larger than any unearthed in the Tigris-Euphrates region itself. The sculptor appears to have drawn from both Mesopotamian and Indus Valley examples to create his own esthetic, she says.

round 1200 to 1000 bce, the rise of camel transport revolutionized Arabian commerce. With the accompanying emergence of sprawling caravanserais, the oasis at Tayma, in the northwest of today’s Saudi Arabia, became an early, vibrant crossroads on the frankincense route from Yemen north to Mesopotamia and the Levant. Thousands of merchants, joined on the caravans by scribes and armed guards, flocked to this vast palm grove, parts of which were enclosed by a six-meter-high (19') wall.

round 1200 to 1000 bce, the rise of camel transport revolutionized Arabian commerce. With the accompanying emergence of sprawling caravanserais, the oasis at Tayma, in the northwest of today’s Saudi Arabia, became an early, vibrant crossroads on the frankincense route from Yemen north to Mesopotamia and the Levant. Thousands of merchants, joined on the caravans by scribes and armed guards, flocked to this vast palm grove, parts of which were enclosed by a six-meter-high (19') wall.

As a whole, Arabia grew rich on this trade. “Each station on the caravan route was like an oil well nowadays,” quips Al-Ghabban, noting that merchants paid the caravanserai owners handsomely for accommodation and food, grazing for their animals, and security. Tayma, and also Dedan (now al-'Ula, 120 kilometers [75 mi] south and west), are mentioned several times in the Bible’s Old Testament.

Tayma’s prosperity attracted the covetous eyes of Babylonian rulers. In the sixth century bce, King Nabonidus went so far as to leave his capital city, Babylon, and occupy Tayma to control the traffic in incense, myrrh, spices, metals and precious stones. He brought his gods with him: A weather-beaten sandstone stele shows faint depictions of the king and Babylonian deities with a cuneiform inscription about a temple dedication.

A more vivid illustration of Tayma’s patchwork of assimilated cultures is epitomized by another sculpture, the so-called “al-Hamra cube,” named for the sanctuary where it was found, and chiseled around a century after Nabonidus, in the fifth or fourth century bce. André-Salvini ticks off its syncretic elements: a “thoroughly Babylonian” priest standing before an altar to the Egyptian bull-god Apis, set against a background of winged emblems and an eight-pointed star that is probably derived from Anatolian civilization. “Despite borrowing imagery from other cultures, the art is totally unique,” she explains. “It possesses a seminal Arabic identity that’s neither Mesopotamian nor Egyptian nor Syrian.”

Around the same time that Nabonidus was occupying Tayma, Dedan was emerging in the fertile al-'Ula valley of fruit orchards, irrigated crops and pastures as the capital of one of the Peninsula’s least-known major ancient powers: Lihyan. Although the city’s ruins were partially excavated in the early 20th century by the French priests Antonin Jaussen and Raphaël Savignac, it is only in the past six years that archeologists from King Saud University have uncovered the full extent of a site that extends some 300 meters (960') long and 200 meters (640') wide across a rocky plain, according to Said Al-Said, the dean of the university’s faculty of tourism and archeology.

Lihyan, declares Al-Ghabban, “was just as big and important as the [later] Nabataean kingdom, even though we know far less about it.” The first-century Roman historian Pliny the Elder makes only a brief reference to it when he calls the Gulf of Aqaba the “Gulf of Lihyan.”

But Lihyan covered much the same territory that was later ruled by the Nabataeans—and more, Al-Ghabban points out: from Aqaba south to present-day Madinah. For some 400 years, until their territory was conquered by the Nabataeans in the second century bce, the Lihyanites controlled the trade routes from China, India and Yemen to Mesopotamia, Syria and Egypt.

Among the spectacular Lihyanite finds of the King Saud University team are three colossal red sandstone statues, unearthed in 2007 near the Kuraybah temple sanctuary north of al-'Ula. Depicting kings, each of the statues in the “Roads” exhibition stands more than two meters (6'5") tall. With stiff arms held close to their sides, the figures strike heiratic poses that hark back to Egyptian models. But the naturalistic depiction of their muscular torsos points to Greek influence. While inventing their own hybrid school of art, the Lihyanite sculptors drew inspiration from their Egyptian and Greek predecessors.

By the first century ce, Mada’in Salih, 22 kilometers (35 mi) north of al-'Ula, became the southern outpost of the Nabataean kingdom and its center for domination of the Arabian caravan routes. The exhibition continues with photographs of elaborate Nabataean tombs cut into honey-hued cliffs and crags. The tomb façades show an eclectic mix of Egyptian cornices, Assyrian bas-relief crenellations and Greco-Roman triangular tympanums. The Romans occupied the region in the early second century, and a stone plaque, unearthed in 2003 by archeologist Daifallah Al-Talhi, attests to the restoration of the city’s ramparts during the reign of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. One of the rare Latin inscriptions found in the Arabian Peninsula, the text credits the local citizens for paying the Roman legionnaires ordered to carry out the construction.

ome 1000 kilometers (620 mi) south of Mada’in Salih, on the western edge of the Rub’ al-Khali (“Empty Quarter”) desert, there thrived another commercial hub, Qaryat al-Faw. For more than 600 years, from the third century bce to the fourth century of our era, it was an oasis of red-clay palaces, temples, markets, an extensive necropolis and at least 120 wells. It was a city of farmers and herders of sheep, cattle and camels that became “a staging point for travelers, merchants and pilgrims from the different kingdoms of Arabia,” according to Abdulrahman Al-Ansari, the veteran archeologist, in charge of excavations there from 1971 until 1995, who wrote about Qaryat al-Faw for the exhibition catalog. As the capital of the Kinda kingdom, Qaryat al-Faw was, he wrote, “an economic, religious, political and cultural center at the heart of the peninsula.”

ome 1000 kilometers (620 mi) south of Mada’in Salih, on the western edge of the Rub’ al-Khali (“Empty Quarter”) desert, there thrived another commercial hub, Qaryat al-Faw. For more than 600 years, from the third century bce to the fourth century of our era, it was an oasis of red-clay palaces, temples, markets, an extensive necropolis and at least 120 wells. It was a city of farmers and herders of sheep, cattle and camels that became “a staging point for travelers, merchants and pilgrims from the different kingdoms of Arabia,” according to Abdulrahman Al-Ansari, the veteran archeologist, in charge of excavations there from 1971 until 1995, who wrote about Qaryat al-Faw for the exhibition catalog. As the capital of the Kinda kingdom, Qaryat al-Faw was, he wrote, “an economic, religious, political and cultural center at the heart of the peninsula.”

The principal market of Qaryat al-Faw—the name means “village of the gap”—was erected using limestone blocks and bricks in three stories surrounded by seven storage towers. Three temples and a separate limestone altar are evidence of diversity in Qaryat al-Faw’s religious life.

Homes rose two stories, supported by stone walls nearly two meters (6') thick and boasting such amenities as water-supply systems and second-floor latrines. One eye-catching mural faintly depicts a multi-story tower house with figures in the windows: Its design resembles similar dwellings today in Yemen and southern Saudi Arabia.

In the exhibition, incense altars from Yemen, bronze statuettes of the Hellenistic god Harpocrates brought from Egypt (where he had once been worshipped as Horus), Roman-style wall paintings and Nabataean ceramics all dramatically illustrate the long reach of Qaryat al-Faw’s mercantile network.

There are personal touches, too. In a mural fragment dated to the first or second century ce, a man—likely the wealthy patron of the mural—resembles a South Arabian Dionysus, with his thick black curls, drooping pencil-thin mustache and wide eyes. He is depicted alongside his toga-clad servant amid vine tendrils and bunches of grapes in a scene that would not appear out of place in a Roman or Ptolemaic villa on the Mediterranean coast. Similarly, a life-size head, cast in bronze, sports the same coiffure of tight curls—a trendy Roman fashion statement adopted by a previously little-known Arabian elite. But according to André-Salvini, the piece was indeed made by an artisan in Qaryat al-Faw, where bronze manufacture was more developed than in Rome or Greece at the time.

Also from a local workshop is an exquisitely proportioned,

long-handled, silver and gilt ladle topped with a delicate ibex head.

Other crafts were mixtures of homegrown productions from glass ateliers and ceramic kilns, and luxury imports, like the blue-and-white ribbed bowl and matching beaker from Italy. Qaryat al-Faw may have grown up on the edge of one of the world’s most forbidding deserts, but its elite indulged refined tastes and embraced

Hellenistic vogues.

“There was a great freedom in the culture, drawing influences from everywhere,” Al-Ghabban explains. “As the exhibition demonstrates, this openness of the Arabian peoples is not a new thing. It has existed for centuries and centuries.”

uring the same period that Qaryat al-Faw prospered

in the west, in the east the kingdom of Gerrha

grew affluent from both maritime and caravan trade in incense, perfumes, pearls, spices, ivory and

Chinese silk.

uring the same period that Qaryat al-Faw prospered

in the west, in the east the kingdom of Gerrha

grew affluent from both maritime and caravan trade in incense, perfumes, pearls, spices, ivory and

Chinese silk.

“The people of Gerrha were masters of overland and sea transport due to their skill in shipbuilding and their knowledge of the seasonal winds,” notes 'Awad bin Ali Al-Sibali Al-Zahrani, Saudi Arabia’s director of museums. “They also reaped the benefits of the rich pearl harvests in this region of the Arabian Gulf and levied customs duties on goods transiting through their country,” he observes in his catalog essay about the kingdom.

Known across the ancient world, the Gerrhans occupied large residences decorated with ivory, pearls and precious stones, ate with gold and silver utensils and slept on gilt beds, according to first-century accounts by Pliny the Elder and the Greek geographer Strabo. But despite its history of more than 600 years, from roughly 300 bce to 300 ce, Gerrha then disappeared without a trace, becoming a kind of Atlantis of the sands whose location has tantalized and frustrated archeologists for years.

Known across the ancient world, the Gerrhans occupied large residences decorated with ivory, pearls and precious stones, ate with gold and silver utensils and slept on gilt beds, according to first-century accounts by Pliny the Elder and the Greek geographer Strabo. But despite its history of more than 600 years, from roughly 300 bce to 300 ce, Gerrha then disappeared without a trace, becoming a kind of Atlantis of the sands whose location has tantalized and frustrated archeologists for years.

Frustrated, that is, perhaps until the gold mask, the gem-studded gold necklaces with rubies, pearls and turquoises and the gold foil stamped with Hellenistic images of Zeus and Artemis were discovered in Thaj in 1998, says Al-Zahrani. Since then, palaces, houses and public buildings have been unearthed alongside an impressive wall 335 meters (1100') long and nearly five meters (16') thick. Based on the substantial mounds of ash and debris that have been detected, archeologists have concluded that Thaj was a major center for pottery-making—and ceramic figurines, incense burners and coins point to the likely existence of temples not yet located, Al-Zahrani adds. The evidence is leading scholars, including Al-Zahrani and Al-Ghabban, to believe the site is Gerrha’s capital.

little more than one-third of the exhibition is devoted to the Islamic period that began in the early seventh century ce, where the exhibit highlights the routes used by pilgrims to and from Makkah and Madinah over some 13 centuries. Throughout this better-known, more recent historic period, “Roads” offers no fewer surprises: For example, on the pilgrimage route from Egypt, Al-Ghabban personally uncovered a pristine 12th-century lintel at the Red Sea port of al-Hawra’. Its floral inscription, in Arabic, quotes part of the “Throne Verse” from the Qur’an, and the graceful letters suggest palm fronds or swans.

little more than one-third of the exhibition is devoted to the Islamic period that began in the early seventh century ce, where the exhibit highlights the routes used by pilgrims to and from Makkah and Madinah over some 13 centuries. Throughout this better-known, more recent historic period, “Roads” offers no fewer surprises: For example, on the pilgrimage route from Egypt, Al-Ghabban personally uncovered a pristine 12th-century lintel at the Red Sea port of al-Hawra’. Its floral inscription, in Arabic, quotes part of the “Throne Verse” from the Qur’an, and the graceful letters suggest palm fronds or swans.

The route to the Holy Cities from Iraq was known from the eighth century as the Darb Zubayda, in honor of the improvements to the road financed by the wife of Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid. Some 200 kilometers (125 mi) northeast of Madinah, the town of al-Rabadha was a major stop along the Darb Zubayda. A center of religious teaching, equipped with mosques, palaces, numerous wells and extensive pastures for grazing camels and horses, the city became a favorite resting spot for pilgrims, from commoners to caliphs—the latter including Al-Mansur, Al-Mahdi and Al-Rashid (who passed through it nine times). Not unlike Gerrha, al-Rabadha too was eclipsed into near-total obscurity when the pilgrimage route shifted in the 10th century. Its location was only confirmed through excavations that began in 1979.

Among the finest objects recovered from al-Rabadha is a large green Iraqi vase with well-preserved decorations. Alongside it are samples of fine lusterware bowls, also from Iraq. A ninth-century wall fragment bearing an inscription in black kufic script, set against a red and yellow-ochre background, resembles similar murals in Iraq, writes Louvre curator Carine Juvin, a scientific advisor with the museum’s Islamic department.

But the most dramatic impact of the Islamic section of “Roads” comes in the dim hall of funerary stelae. Illuminated by subdued spotlights and dating from the ninth to the 16th centuries, recovered from the al-Ma’la cemetery north of Makkah, a row of elegantly inscribed red, purple and gray basalt stones bear names, tribes, lands of origin and occasionally the professions of the dead—and, more exceptionally, the names of the craftsmen who carved the stones.

These are “historical and sociological documents that offer a mirror of Makkan society,” Juvin explains. In addition to the families of the Prophet and his Companions, the memorials commemorate pilgrims from all over the Muslim world, from Andalusia to Iran, Iraq, Syria, Central Asia and India.

Although the existence of more than 600 such stelae, most of which belong to the National Museum in Riyadh or the Qasr Khozam Museum in Jiddah, has been well-known, the first catalogue of them was published only in 2004, in Arabic. Juvin combed through the encyclopedic volume of all 600 inscriptions to select the 18

on display.

To trace the evolution of ornamental and calligraphic styles, she explains, she chose examples from successive eras. Early monuments were inscribed in angular kufic script, notes Juvin, but by the 12th century, a more supple form of writing, the cursive naskh characters, predominated.

Sifting through the inscriptions, Juvin encountered a trove of information about rich and poor, famous personalities and obscure pilgrims from distant lands. One modest, 10th-century stele cites a prestigious genealogy going back nine generations. Another marker from the ninth century pays homage to a slave woman as the mother of her master’s son. Incised with the image of a mosque lamp beneath a pointed dome, one pyramid-shaped monument was erected at the grave of a 12th-century imam from Meknes in Morocco. An unusual circular inscription memorializes a judge from the Caspian Sea region of Tabaristan; he migrated to Makkah in the 1170’s and founded a dynasty of celebrated judges. Most touching of all is perhaps the 12th-century stele dedicated to a father and his daughter who both died during their pilgrimage. According to Juvin, they probably came from Morocco.

Some stelae were re-used: One has a 10th- or 11th-century epitaph for “Ali, perfume-maker by profession,” on one side; on the reverse, framed so as to evoke the shape of a mihrab, or prayer niche, is a mournful elegy from the 12th century for an Andalusian youth. His parents grieve for their boy with a quotation from the 10th-century Spanish poet and mystic Ibn Abi-Zamanin:

Each day death unfurls its shroud

and yet we persist, heedless of what awaits us….

Where are the ones who were our comfort?

Death made them drink the impure cup

They have become captives under the heaped ground.

The final two galleries of objects are stunning: a resplendent, scarlet-red silk cloth and a monumental, hammered silver-and-gilt door, both donated by Ottoman sultans to adorn the Ka’bah; ceramic plaques and paintings of the Holy Cities; and a portrait photograph of King 'Abd al 'Aziz ibn Sa'ud, the founder of Saudi Arabia, along with his sword and cloak.

Nonetheless, I found that it was the funerary stelae that lingered most deeply in my memory. Though in a literal sense they marked the end of the road for those they commemorate, their texts and their artistry transcend their original purpose, making them poignant milestones along the much larger network of roads that not only connected the lands of a very busy ancient world, but also connect that world with our own.

|

Paris-based author Richard Covington writes about culture, history and science for Smithsonian, The International Herald Tribune, U.S. News & World Report and The Sunday Times of London. His e-mail is [email protected]. |

| |

The writer and editors thank Peter Harrigan ([email protected]) for his support in the production of this article. |