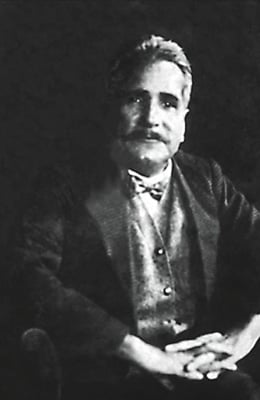

uhammad Iqbal was born on November 9, 1877 in the Punjab city of Sialkot in British-ruled India. His father was a pious Muslim tailor, and his mother a wise and generous woman who quietly gave financial help to the poor and arbitrated neighbors’ disputes. Their home in the lane of the bangle-makers teemed with caring relatives. Muhammad was a happy child who excelled early at learning the Qur’an by heart. When he was four, a teacher and social reformer impressed by the boy’s intellect persuaded his father to enroll him in a local Scottish mission school.

uhammad Iqbal was born on November 9, 1877 in the Punjab city of Sialkot in British-ruled India. His father was a pious Muslim tailor, and his mother a wise and generous woman who quietly gave financial help to the poor and arbitrated neighbors’ disputes. Their home in the lane of the bangle-makers teemed with caring relatives. Muhammad was a happy child who excelled early at learning the Qur’an by heart. When he was four, a teacher and social reformer impressed by the boy’s intellect persuaded his father to enroll him in a local Scottish mission school.

| Muhammad Iqbal was a poet-philosopher whose vision of a homeland for India’s Muslims makes him the spiritual father of Pakistan, the nation created in the partition of British India nine years after his death. Pakistan celebrates Iqbal’s birthday as a national holiday, and India also reveres him. His Song of India has become India’s unofficial national anthem, recited in space by India’s first astronaut as he orbited over the subcontinent in 1984. In Afghanistan, Iqbal is quoted by everyone from the Taliban to feminists and democracy activists. In Iran he is known as “Iqbal of Lahore” and acclaimed for the beauty of his poetry and his love for the Persian language. All through South Asia, the well educated quote Iqbal as Americans might quote Walt Whitman or Robert Frost. So who was this man, and how did he become universally acclaimed, even among people often at each other’s throats? |

|

|

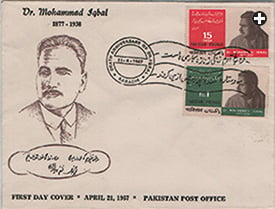

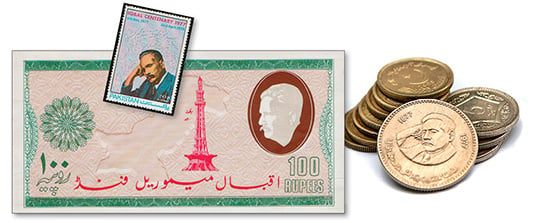

| allama iqbal stamps society |

Young Muhammad was drawn to music and poetry. He delighted in bringing home popular ballads from the marketplace, which he then parodied in impromptu shows. In high school, he mastered the classical skills of the craft of poetry, such as arooz (the science of meter) and abjad (numerology of verses). He wrote chronograms (specific letters stand for a particular date when rearranged), composed ghazals (rhyming couplets) and learned to play the sitar.

At 18, he moved to Lahore to study philosophy, English literature and Arabic at Government College. Lahore at the time was a multicultural city of Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims. Its elegant and extravagant imperial mélange of Mughal and Victorian architecture made it a city full of atmosphere and surprise. Then as now, Lahore was a center of music, poetry and the arts. Mushairas (open poetry readings), held at Bhati Gate, attracted budding poets and poetry lovers of all descriptions, even those who couldn’t read or write. This was where Iqbal first gained a following. He wrote in Urdu, an Indic language, mutually intelligible with Hindi, that developed centuries ago as a lingua franca between the Turkic and Persian invaders of India and those they conquered.

One poem in particular made him famous throughout India: the patriotic Song of India, with its message of communal harmony:

Better than all the world is our India.

We are its nightingales and this is our garden.

That mountain most high, neighbor to the skies,

It is our sentinel; it is our protector.

A thousand rivers play in its lap,

Gardens they sustain, the envy of the heavens is ours.

Faith does not teach us to harbor grudges between us.

We are all Indians and India is our homeland.

y the time Iqbal obtained his bachelor’s degree, he knew six languages—Punjabi, Urdu, Persian, Arabic, English and Sanskrit—three of them well enough to write world-class literature in. He had also read deeply in the libraries of Lahore on philosophy, literature, history and economics, and had mastered Indian and Persian classical music.

y the time Iqbal obtained his bachelor’s degree, he knew six languages—Punjabi, Urdu, Persian, Arabic, English and Sanskrit—three of them well enough to write world-class literature in. He had also read deeply in the libraries of Lahore on philosophy, literature, history and economics, and had mastered Indian and Persian classical music.

|

| suchit nanda / majority world |

| In downtown Lahore, capital of Pakistan, the “Pakistan Tower” (Minar-e-Pakistan) stands at the center of Iqbal Park. |

In 1905, Iqbal left India for England to study modern philosophy at Trinity College Cambridge and law at Lincoln’s Inn in London. At Cambridge, he worked under John McTaggart, a follower of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Europe’s most influential philosopher. To study Hegel in the original German, Iqbal went to Heidelberg in 1907, where he fell in love with the romantic university town. He also fell in love with his beautiful young German teacher, Emma Wegenast. Their relationship was chaste, but from the many letters they exchanged over three decades, there is no doubt that he cared about her deeply. In one letter he wrote: “It is impossible for me to forget your beautiful country where I learned so much. I wish I could see you once more at Heidelberg and from there we would make a pilgrimage together to the sacred grave of the great master Goethe.” The two never made that trip, but Iqbal’s admiration for Goethe never lessened.

The 28-year-old Iqbal was astounded by the riches in the libraries and museums of Europe. He read rare manuscripts of classical Muslim thought, which inspired him to write his dissertation on the development of metaphysics in Persia. It traced the logical continuity of Persian thought from the time of Zoroaster to the founder of the Baha’i faith in the 19th century, and earned him a doctorate from Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich.

In 1908, he returned to Lahore and began teaching philosophy and English literature at Government College and practicing law at the High Court. From then on, he earned his living by the practice of law and his fame from his philosophy and poetry.

|

| from left: allama iqbal stamps society (2), fotosearch |

| In 1977, stamps, a 100-rupee banknote and a coin helped Pakistan commemorate the centennial of Iqbal's birth. |

His mother died in 1914. In grief, he wrote this elegy for her, which resonated with all Indians:

Who would wait for me anxiously in my native place?

Who would display restlessness if my letter fails to arrive?

I will visit thy grave with this complaint:

Who will now think of me in midnight prayers?

All thy life thy love served me with devotion;

When I became fit to serve thee, thou hast departed.

n Europe, Iqbal had begun writing his philosophical works in Persian to gain a wider audience. He continued with The Secrets of the Self (1915) and The Mysteries of Selflessness (1918), which combine Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the superman with the poetry and philosophy of Jalal al-Din Rumi. In these works, he formulated his concept of the self, the divine spark present in every human being since Adam. Man’s legitimate goal, he believed, is to strengthen the self; any behavior that makes for the debasement and perversion of human personality weakens the self. Success does not come from invading the space of others; it comes from growing stronger in oneself. The two works earned him a knighthood in 1923, but the honorific that most attaches to Iqbal’s name in our day is not “Sir” but allama, literally “great scholar.”

n Europe, Iqbal had begun writing his philosophical works in Persian to gain a wider audience. He continued with The Secrets of the Self (1915) and The Mysteries of Selflessness (1918), which combine Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the superman with the poetry and philosophy of Jalal al-Din Rumi. In these works, he formulated his concept of the self, the divine spark present in every human being since Adam. Man’s legitimate goal, he believed, is to strengthen the self; any behavior that makes for the debasement and perversion of human personality weakens the self. Success does not come from invading the space of others; it comes from growing stronger in oneself. The two works earned him a knighthood in 1923, but the honorific that most attaches to Iqbal’s name in our day is not “Sir” but allama, literally “great scholar.”

In his collection of poetry The Call of the Marching Bell (1924), Iqbal stressed that God had created the universe for man, not the other way around. So, Iqbal reasoned, man should not be the slave of the universe, but its master. Therefore, the duty of a Muslim was to discover the laws of nature by observation and experiment, and to strive to understand all things on earth. Whatever knowledge the senses of man discovered about nature would certainly be fully compatible with the will of God. This led Iqbal to conclude that there was no conflict between European science and Islam.

|

| left: faseeh shams / drik, riGht: international iqbal society |

| Left: In 2003, Pakistan renamed the airport in Lahore after Iqbal. Right: This portrait of Iqbal with his son Javed probably dates from near 1920. He had two books of philosophy to his name, and he would enter politics a few years later. |

Iqbal’s writings frequently dwell on the past glories of Islamic civilization, but this theme never prevented him from considering the wisdom and ideas of other cultures and societies. No other Muslim thinker was as familiar with western writers and philosophers as he was. Iqbal displayed a remarkably international perspective when delineating the literary constellations to whom he was personally indebted:

I owe a great deal to Hegel, Goethe, Mirza Ghalib, Mirza Abdul Qadir Bedil and Wordsworth. The first two led me into the “inside” of things; the third and fourth taught me how to remain oriental in spirit and expression after having assimilated foreign ideals of poetry, and the last saved me from atheism in my student days.

In this pantheon, Goethe was at or near the top. “Only when I realized the infinitude of Goethe’s imagination,” wrote Iqbal, “did I discover the narrow breadth of my own.” And of Goethe’s works, none was more important to Iqbal than The West-Eastern Divan, a collection of lyrical poetry in the Persian style consisting of parables, historical allusions and religiously inclined poems that try to bring together orient and occident. Goethe bemoans that the West had become too materialistic and calls on the East to provide a message of hope to resuscitate spiritual values. Iqbal’s answer to Goethe was his Message of the East, Persian and Urdu poems published in 1923 and 1924.

|

| Yousaf Khan (3) |

| Left: On the wall outside what was his residence in Heidelberg, Germany, a plaque reads: “Mohammed Iqbal, 1877-1938, national philosopher, poet and intellectual father of Pakistan, lived here in 1907.” Right: Not far away, the boulevard bearing his name leads along Heidelberg's Neckar river. |

In one poem,“Dialogue between Man and God,” Iqbal argued that the universe is not complete, but a continuing process:

You created the night and I the lamp.

You created clay; I fashioned from it the wine cup.

You created deserts, mountains, wastelands.

I made them into orchards, gardens, flower-beds.

n another, “The Wisdom of the West,” Iqbal lashed out at the brutality shown by European powers in the First World War. A man who has died a clumsily painful death complains to God, asking Him to retrain the Angel of Death:

n another, “The Wisdom of the West,” Iqbal lashed out at the brutality shown by European powers in the First World War. A man who has died a clumsily painful death complains to God, asking Him to retrain the Angel of Death:

The West develops wonderful new skills

In this as in many other fields.

Its submarines are crocodiles;

Its bombers rain destruction from the skies;

Its gasses so obscure the sky,

They blind the sun’s world-seeing eye.

Dispatch this Old Fool to the West

To learn the art of killing fast—and best.

|

| faseeh shams / drik |

Iqbal's last home in Lahore is now a museum that attracts visitors from throughout the country and South Asia. |

Following custom, at age 16 Iqbal had been wed to the daughter of a Gujarati physician. The marriage was unhappy and ended in divorce. In 1913, he remarried, and the union produced a son, Javed. Some of Iqbal’s best-loved works are addressed to his son, including the Javed Nama (The Book of Javed, 1932) and these couplets from Gabriel’s Wing:

Do not be beholden to the West’s artisans,

Seek thy sustenance in what thy land affords.

…

My way of life is poverty, not the pursuit of wealth;

Barter not thy Selfhood; win a name in adversity.

aved followed his father’s advice, becoming a noted Pakistani lawyer and judge. As to the first line of the second couplet, Javed had this to say about the family finances in his four-volume biography of his father:

aved followed his father’s advice, becoming a noted Pakistani lawyer and judge. As to the first line of the second couplet, Javed had this to say about the family finances in his four-volume biography of his father:

“We were always short of money. My mother wanted to buy a home instead of always renting so she wanted my father to take his law practice seriously. I can still recall my mother crying and complaining that while she was working like a servant, my father was lying on a couch and writing poetry. When upbraided like this, my father would laugh his embarrassed laugh.”

Iqbal became increasingly concerned about the status of the Muslim minority in a soon-to-be-independent India. He entered politics and was elected to the Punjab Legislative Council in 1926. In 1930, he became president of the All-India Muslim League at its session in Allahabad and outlined his vision for India’s Muslim-majority areas in his presidential address on December 29, 1930:

I would like to see the Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single state. Self-government within the British Empire, or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated Northwest Indian Muslim state appears to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of Northwest India.

This speech is seen as the birth of the idea of Pakistan, though Iqbal did not demand an independent Muslim state, only a self-governing one:

The principle of European democracy cannot be applied to India without recognising the fact of communal groups. The Muslim demand for the creation of a Muslim India within India is, therefore, perfectly justified, ... inspired by the noble ideal of a harmonious whole which, instead of stifling the respective individualities of its components, ... affords them chances of fully working out the possibilities that may be latent in them.... For India, it means security and peace resulting from an internal balance of power; for Islam, an opportunity to ... mobilise its law, its education, its culture, and to bring them into closer contact with its own original spirit and with the spirit of modern times.

|

| left: international iqbal society, Right: alexander lunde (2) |

| An undated portrait of Iqbal in his later years. In what became a widely quoted political aphorism, he said, “Nations are born in the hearts of poets; they prosper and die in the hands of politicians.” Right: Along Portugal Place in Cambridge, a plaque commemorates his university residence in 1905-1906. |

In 1931 and 1932, Iqbal represented Indian Muslims at the London Anglo-Indian Round Table Conferences on the political future of India. One of his most quoted political sayings was: “Nations are born in the hearts of poets; they prosper and die in the hands of politicians.” On these as on other trips to England, he usually found time to go up to Cambridge to address Trinity College students.

After leaving England in 1932, he went on to Spain to pray at the former Great Mosque of Córdoba and to Afghanistan to attend meetings marking the establishment of Kabul University. Upon his return home, he began suffering from a mysterious throat ailment. By the mid-1930’s, his health had deteriorated so much that he had to decline to give a series of Rhodes lectures at Oxford.

But still he did not put down his pen, composing these lines a few days before his death:

The departed melody may return, or not!

The zephyr from Hijaz may blow again, or not!

The days of this Faqir [poor man] have come to an end;

Another seer may come—or not!

qbal died in Lahore in the early hours of April 21, 1938, prompting an outpouring of grief throughout the subcontinent. Within hours, Indians of all faiths swarmed to his house. A gravesite was quickly identified for him on hallowed ground between the Mughal-era Imperial Mosque and Lahore Fort. That afternoon, newspaper supplements about his life began to appear. In the evening, a funeral procession of 20,000 people snaked through the streets of Lahore. As it passed an orphanage, the children lowered black flags they held in their hands as a sign of respect: The Cry of the Orphan had been Iqbal’s first successful long poem, written nearly 40 years before. At 9:45 p.m., 50,000 people stood in silence as his body was lowered into the grave.

qbal died in Lahore in the early hours of April 21, 1938, prompting an outpouring of grief throughout the subcontinent. Within hours, Indians of all faiths swarmed to his house. A gravesite was quickly identified for him on hallowed ground between the Mughal-era Imperial Mosque and Lahore Fort. That afternoon, newspaper supplements about his life began to appear. In the evening, a funeral procession of 20,000 people snaked through the streets of Lahore. As it passed an orphanage, the children lowered black flags they held in their hands as a sign of respect: The Cry of the Orphan had been Iqbal’s first successful long poem, written nearly 40 years before. At 9:45 p.m., 50,000 people stood in silence as his body was lowered into the grave.

At the centennial of his birth, in 1977, flower-decked processions marched throughout the country, and his portrait and his best-loved verses hung from public buildings. Iqbal’s last home in Lahore is now a museum, attracting visitors from all over South Asia and beyond. Historical markers grace the places where he lived in Cambridge and Heidelberg. Both homes are close to their respective rivers, the Cam and the Neckar, along which he loved to take long, contemplative walks. The road along the Neckar now bears his name: Iqbal-Ufer, or Iqbal Bank. And his evocative poem “An Evening on the Banks of the River Neckar” is carved on a memorial stone near the river:

The caravan of stars

Proceeds without a whisper or a sound;

Mountain, forest, river,

All in lull;

Nature seems lost in contemplation.

O heart, you too be still.

Hold thy grief to thy bosom, and sleep!

|

Gerald Zarr ([email protected]) is a writer, lecturer and development consultant. As a us Foreign Service officer, he lived and worked for more than 20 years in Pakistan, Tunisia, Ghana, Egypt, Haiti and Bulgaria. He is the author of Culture

Smart! Tunisia: A Quick Guide to Customs and Etiquette (Kuperard, 2009).

|