|

| Photocuisine / Alamy |

| Though handmade pastas remain a boutique food craft, since the 19th century most pasta has been made by the mechanized extrusion of dough through perforated discs, after which it is sliced, dried and conveniently packaged. |

Local legend has it that when the Arab conqueror of Sicily, Asad ibn al-Furat, landed with his fleet on the southern shore of the island in 827, one of his first orders of business was to muster up food for his troops. Quickly surveying the local resources, Asad’s cooks caught sardines in the harbor, harvested wild fennel, currants and pine nuts from the surrounding hills, and combined them all with an ingredient then unknown in Europe, which the invading Arabs had brought with them in the holds of their ships: pasta.

Today, pasta con sarde, or pasta with sardines, is one of Sicily’s signature dishes. Yet as legends go, this version of how pasta became a staple of Italian cuisine is far less familiar than the tale of Marco Polo’s supposed discovery of noodles in China in the 13th century—a tale that has been subject to more spin than a forkful of spaghetti.

In the first place, Polo actually wrote in his account of his travels that the noodles he ate in the Orient were “as good as the ones I have tasted many times in Italy,” and likened them to vermicelli and lasagna. Second, there are commercial documents recording pasta shipments and production in Italy long before Polo’s journey. Most convincingly, scholars have pointed out that the whole story was a deliberate fabrication published in the late 1920’s by editors of The Macaroni Journal, a trade publication of North American pasta manufacturers.

|

| British Library |

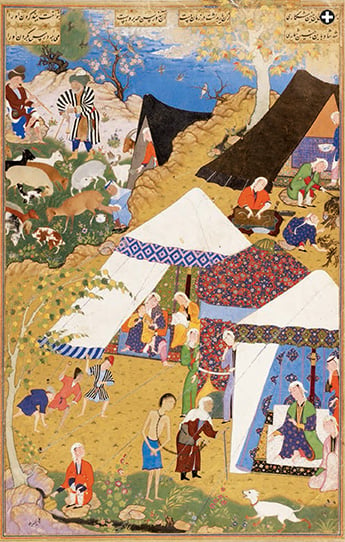

| This painting comes from the Khamsa of Nizami, a book of masterpiece illustrations produced in mid-16th-century Tabriz. It depicts an episode in the 12th-century Persian epic tale of Majnun—shown here in chains—and Layla, who awaits his arrival at her tent. In the background, at upper right, artist Mir Sayyid Ali included four cooks: One holds meat over a fire tend- ed by another; one brings a bowl, and one woman uses both hands to roll what is likely reshteh, a Persian word for pasta. |

While the Asad ibn al-Furat tale may be no less fanciful, there is evidence to suggest that pasta may have come from the Middle East. Still, the story of the humble noodle’s journey from east to west has as many twists and turns as a strand of fusili, and is often as slippery.

No matter what its shape (Italian food writer Oretta Zanini De Vita’s scholarly Encyclopedia of Pasta identifies more than 300 shapes) or its flavor (from pumpkin to squid ink), pasta is, essentially, flour and water mixed into dough that is rolled out, cut and cooked by boiling in liquid. This last step is one way pasta is distinguished from bread, which is baked or fried. Another distinction comes with the type of wheat used in the flour.

Pasta is generally made from hard durum wheat (Triticum turgidum var. durum), which is loaded with the gluten that helps pasta maintain its shape both during manufacture and later in boiling water. With some 30 percent more gluten than common wheat (Triticum vulgare), and with a naturally lower moisture content, durum flour mixed with water dries into a hard but reconstitutable foodstuff—pasta secca in Italian. Therein lies another crucial distinction.

Pasta fresca, as its name implies, is fresh pasta. Soft and pliable, pasta fresca is meant to be cooked promptly. While it can be made with durum, most cooks find all-purpose flour from common wheat, sometimes enriched with eggs, easier to work, especially by hand. Pasta secca, on the other hand—the kind of pasta commonly found on grocery-store shelves—can be made only with durum flour, because durum’s unique properties permit its nearly indefinite preservation. Writing in the 14th century, the Mamluk civil servant Al-Umari cited a government report that claimed that the durum wheat of North Africa “could be stored for 80 years in silos,” and, in the 11th century, Andalusian geographer Al-Bakri boasted that one of the characteristics of Toledo is that “its wheat never changes or goes bad over the years.”

|

Aside from pasta, durum wheat is most widely used in North African Arab cuisine for couscous, which is made of coarsely ground dried semolina dough. A staple of the North African diet, couscous is also popular in southern Europe, especially in Sicily, where the dish appears rou- tinely on the menus of trattorias throughout Palermo and is regarded as a staple by many modern Sicilians. Meanwhile, whole-grain durum wheat is also popular throughout the Middle East as bulgur or burghul—an Arabic word that comes from the Persian for “bruised grain”— which is durum that is steamed or parboiled, then dried and crushed. It is a basic ingredient in such dishes as tabbouli, kibbe and pilafs. In Tunisia, it is called borghol; in Saudi Arabia, it is jarish, popular especially in Najd and the Al-Hasa Oasis of the Eastern Province. In Jordan, bulgur sometimes replaces rice in that country’s nation- al lamb dish, mansaf, while in Egypt and Syria, roasted grains of unripe durum, called frikah (or farik), add body and a nutty flavor to pilafs and soups.

|

The key to tracking down pasta’s origins, therefore, lies in finding a common answer to three questions: Who cultivated durum wheat, or at least had access to a regular supply of it? Who first processed durum flour into dough, shaped it and dried it? And then, who pioneered the method of cooking those preserved shapes in boiling liquid?

The questions go back millennia. One of the world’s oldest domesticated grains, durum emerged as early as 7000 bce as a natural mutation or hybridization of emmer wheat, a wild grass native to the Fertile Crescent and one of the first cereal grains cultivated there roughly 10,000 years ago. (Today emmer wheat is also known as spelt; in Italy it is farro.) In addition to its long shelf life, another advantage of durum, people found, is that it is a so-called naked wheat. This means that the hulls encasing the grain kernels easily break away as chaff during threshing. Its disadvantage is that, when milled, its flour—also known as semolina—is hard and granular rather than the soft and powdery “all-purpose” flour that comes from soft wheat. These characteristics were apparent to the world’s first bakers, whoever and wherever they were: Soft wheat produced the better bread, while durum was better suited to porridges, whole-grain concoctions and, eventually, pasta.

From its origins in the Middle East (most likely the Fertile Crescent), durum—with its intrinsic pasta-making potential—spread far and wide, though just how far and when are questions historians and paleobotanists debate. The Chinese are often credited with the invention of noodles, and it is true that by 2500 bce they were growing wheat—but not durum. It was common wheat, and anthropologists generally agree that the grain, and possibly the technique of milling it, were introduced to China by West Asian merchants via the Silk Roads. Linguists have found that, in China, many non-Chinese food terms “have Near Eastern names, borrowed from Arabic or Persian,” according to the late Herbert Franke, a founder of the University of Munich’s Sinological Section and an author of the Cambridge History of China.

|

| Giorgios Psakis / Alamy |

| This illustration showing five varieties of durum wheat was produced in the united States in 1900. The group was called “Macaroni wheats” because the high gluten content of durum wheat helps pasta hold its shape. |

“It should be noted that the words for ‘noodles’, ‘Ravioli’ and similar flour-made dishes are all Turcic [sic],” Franke wrote. “This points to the fact that the dishes themselves were originally non-Chinese and may have been introduced into China from the Near East.... This would mean that even such dishes as chiao-tzu [dumplings], which have become a staple and household feature in Chinese cuisine, might have come to China from the ‘Western barbarians.’”

We know that, by the Han Dynasty in the late third century bce, the Chinese were making mein (noodles), but the evidence suggests that early Chinese noodles were pasta fresca, not pasta secca. As late as the 12th century, the Chinese traveler Chau Ju-kua noted with wonder that the wheat in Muslim Spain was “kept in silos for tens of years without spoiling”—an unlikely remark to make if he had known durum wheat back home. East Asians also relied on flour from other sources, such as rice, to make noodles. In fact, Polo’s surprise at encountering noodles on the Indonesian island of Sumatra was that they were made with “farina di alberi” (“flour from trees”), that is, the starchy pith of either the sago palm or the breadfruit tree. It was samples of those “exotic” noodles—not pasta secca—that Polo brought back to Italy.

|

| TOP: Fotosearch / Feldman & Associates. Lower: Imagebroker / Alamy |

| Triticum turgidum var. durum has been known and cultivated by humans for at least eight thousand years. |

Looking west to Greece and Rome, there are numerous references to what is believed to be durum wheat scattered throughout classical sources, as well as archeological evidence supporting the early presence of that grain in the Greco-Roman world. Many of the references come from medical writers. The second-century Greek physician Galen compared durum’s taste to that of barley, but cautioned readers to lay off the semidalis, a word derived from samid or semidu, the Mesopotamian word for semolina.

Most writers, however, praised durum’s fiber-rich goodness, much as nutritionists do today. The first-century Roman agronomist Columella, who served as a tribune in Syria, reported that durum wheat thrived best in dry climates, like those of North Africa and Sicily, where modern agronomist Renzo Landi of Florence’s Academia dei Georgofili points out that locally minted Roman coins depict sheaves of durum, distinguishable by its long awns. Such coins, says Landi, “confirm the presence of durum wheat very exactly to the time of the Roman republic.”

|

Italians were eating pasta long before they had a collective noun for it. Pasta is a word that comes to us unchanged from the Latin one that meant “paste,” “dough” or “pastry cake.” It was itself a loan word from the Greek for a collation of grain and water that was sprinkled with salt—pastos—that itself comes from another Greek word, passein, “to sprinkle.” The earliest written use of the word pasta, in the modern sense, came in 1584, in a guide to organizing banquets written by Giovan Battista Rossetti, head steward of the Duchess of Urbino.

Prior to this, pasta was more commonly referred to by its particular shapes. Among the most popular—all made by hand—were gnocchi (dumplings, from noccio, “a knot of wood”); lasagne (“sheets”); vermicelli (“little worms”); tagliatelle (ribbon-shaped strips or “cuttings,” from tagliare, “to cut”); tortellini (“little pie”) and ravioli, whose derivation is uncertain, but which was referred to as early as 1100 as raviolo and described a century before that by Ibn Butlan as sambusaj, indicating possible culinary (if not lexical) origins in Persian dough-wrapped meats.

Nudel (“noodle”) is likely of 18th-century German origin, while the multitude of pasta shapes on modern grocery-store shelves are products of mostly 19th-century industrial extrusion technologies that pushed pasta dough through die-cast copper discs, each perforated with holes of various shapes, from circles and ribbon slits to wagon wheels and alphabet letters.

But of all the names for pasta, the most common is macaroni, or maccheroni in Italian. This catch-all term covers a wide range of types, from the specific (short, tubular, curved pasta) to the general (any type of pasta, long or short, tubular or flat, string-like or curled). Thus, while Maestro Martino’s macharoni alla siciliana were string-shaped and his macharoni alla romana (“in the Roman fashion”) were long and flat like fettuccine, early references to macharoni/maccheroni also indicated short, round, gnocchi-like pasta. This rounded shape helps explain how maccheroni could tumble down the fluffy, cheesy slopes of Boccacio’s fanciful Parmesan mountain. The word macharoni appeared, along with vermicelli, as early as the 13th century, in texts composed by Italian Jews.

|

| Samuel Hieronymous Grimm/V&A Museum/Bridgeman Art Library |

| When fashion is not enough: An 18th-century english gentleman, perhaps a member of the Macaroni club, strikes a pose. |

Yet despite its widespread use and familiarity, the origins of the word macaroni remain elusive. Many believe it derives from the Latin maccare, “to bruise, batter or crush,” a term which suggests the kneading of dough and which survives in the Italian ammaccare, meaning “to pulverize or squeeze together.” (In Sicily and Puglia, puréed fava beans, called macco, are a regional favorite.) A vestige of the same word survives in the Italian for rubble, macarie, and in the name of the ground-almond confection called “macaroon.”

Greek origins are also suggested. Makaria means “food made from barley and water” in late Greek, the patois of the eastern Mediterranean from the third to the eighth centuries—broadly, the time frame within which pasta secca came to the West. The term also translates as “food of the blessed,” from the Homeric Greek macarios, “blessed.” In southern Italy, when it was part of the classical Greek world, a thin noodle soup served at funerals was called macaria or macaria-aionia, “eternal food of the blessed.” As late as 1548, Ortensio Lando, a medical doctor from Modena, paid homage to macaroni’s possible Greco-Sicilian roots in his Commentario della Piu Notabili et Mostruose Cose d’Italia (A Guide to the Most Notable and Monstrous Things of Italy) by enviously remarking to a friend that “in a month, if the winds do not fail you, you will reach the rich island of Sicily, and you will eat those macheroni, which have taken their name from the beatifying.”

Macaroni may also hint at a connection between the culinary and theatrical arts. In the Atellan Farce, a collection of bawdy and buffoonish skits performed for the lower classes in ancient Rome, the name of the clown was Maccus. To medieval Italians, any stupid, bumbling figure whose antics recalled those of Maccus was thus a maccherone. Maccus went on to inspire the roguish character of Pulchinella in the commedia dell’arte, a masked, improvisational street theater popular during the Italian Renaissance. Pulchinella’s pointy-nosed, black-and-white mask was called a macco, and his distinguishing props included a heaping plate of macaroni and large wooden spoon. The pasta symbolized gluttony, while the spoon served the dual purpose of accommodating Pulchinella’s voracity and clobbering anyone who attempted to curb it. By the 17th century, Pulchinella was also known as Punchinello, and he traveled north to become the puppet character Punch of “Punch and Judy” fame who, having ditched the macaroni, yet retained the spoon, the better to whack at his equally pugnacious co-star.

This association of macaroni with fools crossed the Atlantic and appeared in the familiar American Revolutionary War jingle “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” In Elizabethan England, Italian fashion, cuisine and customs were de rigueur for those wishing to put on worldly airs. Some took this to extremes, and by the 18th century, the derisive epithet for an overdressed, often foppish poseur of Italian mannerisms was “macaroni.” In London, undeterred by their critics, the city’s “macaronis” in 1760 formed The Macaroni Club, and it was their outlandish hairstyles that inspired 19th-century English sailors to nickname a colorfully crested Antarctic species the macaroni penguin. Similarly, when the American Revolution broke out in 1775, “macaroni” was equated with the hairstyle, and it was to mock such pretense that the homespun, irreverent Yankee Doodle “stuck a feather in his cap and called it ‘macaroni.’”

No less intriguing, and no less intricate, is the theory that macaroni is a word rooted in Arabic. Duwayda (“inchworm”) is the Arabic name of an early, Tunisian form of vermicelli, in which the pasta is broken into short pieces. (See sidebar, page 21.) Linking the two ends of fresh duwayda yields little rings, called qaran, which comes from the Arabic qarana, “to join.” Once joined, they are—to use the Arabic past participle—ma-qrun or maq-runa. Not a long leap from there to macaroni.

While food writer Clifford Wright is guarded in citing this theory in A Mediterranean Feast, food historian and cookbook author Nawal Nasrallah, in Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine, is more direct: “In Iraq up until the [nineteen-]fifties, pasta in southern regions was called maqarna,” Nasrallah noted, while “in more cosmopolitan areas such as Baghdad, that word was already passé. They replaced it with the classier Italicized ma’karoni.”

Maqarna and itriyya aside, pasta has been known by a host of names throughout the Middle East. In addition to the Akkadian connection between semidu and semolina, a 3700-year-old Babylonian recipe for “spleen broth,” found among the cuneiform tablets of the Yale Babylonian Collection, calls for adding “bits of roasted qaiatu-dough.” Nasrallah suggests that this ingredient could be interpreted as fine, thin noodles.

“The Akkadian qatanu, from which qaiatu was possibly derived, means ‘to become thin and fine,’” she explains. “The Arabic qitan, with its plural, qaiateen, is ultimately derived from this Akkadian qatanu, which means ‘strings’ or ‘cords.’ Therefore, there is the possibility that the qaiatu-dough was flattened thin and cut into strips like qatanu—strips or cords.” The fact that they are toasted before going into the pot—still a common technique in many pasta-based soups and pilafs—also suggests it was not just any dough but a sturdy sort—such as dried pasta.

Toasted noodles are still sold in the markets of Iraq, Nasrallah noted. There they are known as rishta, a Persian word that translates as “thread.” Recipes for rishta appear after the 13th century in Arabic cookbooks, replacing an earlier term for noodles, lakhsha, which is Persian for “slippery.” Renowned food historian Charles Perry theorized that the shift in terminology was for the sake of clarification: Lakhsha were noodles used exclusively in the wild-ass soup that possibly went out of vogue by the 13th century. (The word lived on, however, in other languages and cultures: Today, laksa is a spicy Chinese-Malay noodle soup, and in regions once part of or bordering the Ottoman Empire, it survives as laska in Hungary, lapsa in Russia, lokshina in Ukraine, lakstiniai in Lithuania, lakhchak in Afghanistan and lokshen in Yiddish.)

Rishta, now often transliterated reshteh, remains the central ingredient in many traditional Persian dishes, such as reshteh polow (rice with noodles) and ash-e reshteh (noodle soup). This latter dish is also called ash-e pushteh-pa, or “pilgrim’s soup,” traditionally served on the eve of a loved one’s departure on pilgrimage to Makkah, or on the occasion of a son leaving the house to make his way in the world.

“Dishes containing noodles are traditionally prepared at times of decision or change so that the ‘reins (of life) may be taken in hand,’” according to Margaret Shaida, author of The Legendary Cuisine of Persia. In pre-Islamic Iran, noodle soup was eaten at the beginning of each month, Shaida notes, a custom that survives in Iran today, where the soup may be served at the first prayer meeting of every month. Ash-e reshteh is also the food of religious pledges (nazr) invoking God’s intervention in family matters, such as the safe return of a loved one after a long journey or the recovery of a sick child. “Noodle soup is specially favored for pledges since the tangle of noodles is thought to resemble the tangle of paths in one’s life,” Shaida observes. |

But did the Greeks and Romans use their durum to make pasta? Yes and no. Greek laganon was a broad, flat sheet of baked or fried dough made with flour and oil. It is often cited as a pasta prototype, along with its Roman derivative, laganum. The fourth-century-bce Greek poet Archestratus of Gela frequently refers to laganon in his Life of Luxury, a sort of gourmet guide to the Mediterranean. In the Roman era, Athenaeus’s Deipnosophistae (Philosophers at Dinner), a how-to manual for hosting highbrow dinner parties, claimed to have cribbed a recipe for laganon from the first-century Greek writer Chrysippus of Tyana.

Roman cooks indeed cut laganum into strips called lagani or lagana, and layered them with other ingredients in a baking dish, thus producing the apparent culinary and lexical ancestor of lasagna. “Alternate the lagana with ladles of the filling,” read the instructions in De Re Coquinaria (On Cooking), a fourth-century compilation of recipes attributed to the legendary first-century gourmand Marcus Gavius Apicius, a man so devoted to fine dining that he supposedly took his own life when he realized he didn’t have enough money left to maintain his lavish lifestyle. The more abstemious statesman Cato the Elder, who lived from 234 to 149 bce, wrote a practical guide to farm management and husbandry called De Agricultura (On Agriculture), in which he recorded a recipe for a sort of cheesecake that blended farinae siligneae (common flour) with alicae primae (finest semolina) to form a tracta, a sort of pie crust. Later, between 68 and 65 bce, the Roman poet Horace wrote that he found nothing more comforting after a long day hobnobbing in the Forum than to come home to a warm tureen of leeks, chickpeas and lagani.

|

| Nicola ALbon / Alamy |

| Greek flatbread, called laganon or lagana, may be a predecessor both of pasta in the northern Mediterranean and—after romans layered it with fillings—lasagna. |

Yet for all their details, not one of these sources discusses drying or boiling the durum dough, which indicates that these foods were still not quite pasta secca. Baked laganum was probably closer to Jewish matzo, while the fried variety resembled fritters or beignets. Pasta-type foods are, in fact, “conspicuous in classical sources only by their absence,” according to Robert Sallares, author of The Ecology of the Ancient Greek World. This begs a further question: Considering both Greek and Roman inventiveness, as well as pasta’s relative simplicity, how is it possible that the idea of pasta secca never occurred to either the Greeks or the Romans?

Some scholars speculate that, given ancient milling technology, durum was too difficult to grind fine enough for pasta-making. Others believe that there was simply no place for pasta in the classical world’s hierarchy of carbohydrates.

“In the Mediterranean, from antiquity to the Middle Ages, gruels and breads were the two fundamental, cereal-based foods,” explains Françoise Sabban of the École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris. She is co-author, with her husband, Silvano Serventi, of the scholarly Pasta: The Story of a Universal Food. The distinctive methods of preparing bread and gruel, she suggests, kept them from cross-fertilizing each other. Like pasta, bread is made from kneaded dough, but unlike pasta, bread is baked in dry heat; gruels and porridges are boiled like pasta, but, unlike pasta, they are made from whole or crushed grains, not from flour. “In this context, pasta was unthinkable because it straddled both categories, and therefore belonged to neither,” says Sabban.

The earliest indication of these categories emerging in the West appeared in the seventh-century writings of Isidore of Seville, who described laganum as “a broad, flat bread, which [is cooked] first in water and then fried in oil.” A familiar approximation might be the crispy fried noodles that accompany chow mein or that serve as appetizers in many Chinese restaurants in the West.

Still, classical sources aren’t entirely devoid of hints that point in an easterly direction for pasta’s possible origins, as an etymological poke through the poet Horace’s simple supper reveals.

Horace hailed from Venusia (today Venosa), a Greek commercial city bordering Apuglia, the “heel” of Italy’s boot-shaped peninsula. It was a region occupied at various times by Byzantines, Lombards, Normans and, during the Middle Ages, Arabs. Yet through it all, and even to this day, Horace’s humble bowl of chickpeas, leeks and lagani remained a regional favorite, known as ciceri e tria or pasta e ceci, a classic dish of chickpeas (ceci) and wide, ribbon-shaped pasta, traditionally laganelle, a rustic form of tagliatelle. Aside from the obvious lexical connections between Horace’s lagani and laganelle (not to mention laganatura, a southern Italian term for “rolling pin”), that little four-letter word tria is another regionalism of even greater significance. The word derives from the Greek itrion, meaning a cake or thin, unleavened bread. Yet by the fifth century, its Latin cognate itria had come to mean something else entirely.

|

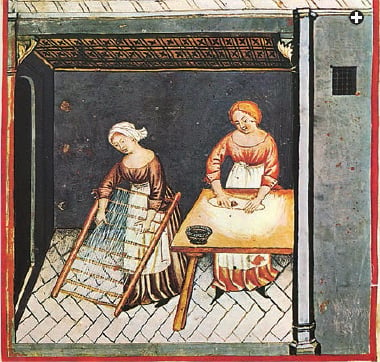

| TACUINUM SANITATIS |

| In the 14th century, book-makers in Lombardy published an illustrated Latin edition of the encyclopedic 11th-century health manual by Ibn butlan of baghdad. It included a recipe for pasta, called trij, and this illustration of women rolling and drying it. |

“As to making vermicelli [itria] on the festival, if it is for drying them, it is forbidden. If it is for the pot [cooking right away], it is permitted,” according to the Jerusalem Talmud, a collection of writings on Jewish law composed in the holy city during the late fourth and early fifth centuries. The passage concerns whether or not boiled dough qualifies as unleavened bread, but its importance goes far beyond a rabbinic debate. For here is the earliest written evidence that people in the Levant were not only boiling dough but, most importantly, were drying and preserving it in long strands, which they called itria. This word survives as itriot in Hebrew, itriyya in Arabic and as tria in southern Italy, all meaning the same thing: pasta.

“Tria is what they traditionally call pasta in Calabria, in Naples, and in many of the towns and villages in central Sicily,” says anthropologist and Sicilian native Franco La Cecla, author of Pasta and Pizza. Nibbling on an appetizer-sized square of the latter entrée in a quiet neighborhood trattoria in Palermo, La Cecla says there is no doubt among Sicilians as to who introduced the island to pasta and the technique of its manufacture: Arabs.

“The Arabs developed most of the irrigation and agricultural techniques in Sicily during the great waves of conquest in the ninth century,” says La Cecla. “It is commonly known here that they also brought with them the methods for making pasta.”

There is more to La Cecla’s claim than mere legend. Early Arab medical writers—like their Greek and Roman forebears—recognized the health benefits of wheat, and in their discussions of its various preparations, they included pasta. As early as the ninth century, the Syrian physician and lexicographer Ishu bar Ali referred to itriyya as dried strands of semolina dough that are boiled. One of the foremost medical authorities of the Middle Ages, Ishaq ibn Sulayman of Egypt, discoursed on the preparation of pasta in his 10th-century Kitab al-Aghdhiya wa’l-Adwiya (The Book of Foods and Cures, known in the West as The Book on Dietetics). Further east, the late-10th-century lexicographer al-Jawhari, who hailed from the Silk Road city of Otrar in southern Kazakhstan, defined itriyya as a food similar to hibriya, or “hairs” (possibly “flakes”) made from wheat.

The earliest written reference to pasta and pasta-making on Italian soil comes from none other than the renowned medieval Arab geographer al-Idrisi. Describing the coastal towns of northern Sicily in his Kitab Nuzhat al-Mushtaq fi Khtiraq al-‘Afaq (The Book of Pleasant Journeys into Faraway Lands), composed in 1154 for his Norman patron, the Arabophile King Roger ii of Sicily, al-Idrisi remarked on “a delightful settlement called Trabia,” some 30 kilometers (18 mi) east of Palermo, where “ever-flowing streams propel a number of mills. Here there are huge estates in the countryside where they make vast quantities of itriyya which is exported everywhere: to Calabria, to Muslim and Christian countries. Very many shiploads are sent.” (See sidebar, The Last Pasta-Maker of Trabia.)

|

The Sicilian coastal town of Trabia, which al-Idrisi so significantly described, still roosts on a hillside overlooking the Mediterranean, about a half-hour’s drive from Palermo. The “huge estates” of which he wrote are gone now, as are the mills that once ground acres of durum wheat into semolina. The location of the last mill, which disappeared around the middle of the last century, is now a car wash. Yet in the back room of an inauspicious little trattoria, about midway along Trabia’s main thoroughfare, the town’s last commercial pasta-maker still hand-makes a boutique supply of anellitti, tagliatelle and other favorites for a mostly local clientele.

“Making pasta was something my father taught me how to do,” says owner Matteo Barbera. “I only make it on Saturdays and Sundays. I use flour, eggs and water. That’s it.” The flour he buys from Tomasello, Sicily’s lone industrialized pasta manufacturer, a firm founded in 1910 in Casteldaccia, a few miles west. Yet even the flour is no longer local: It is shipped to the island from the United States and Russia.

Still, Barbera is proud of Trabia’s pasta heritage, which is promoted right alongside seafood and crabapple-like medlars in the town’s tourism literature.

“It is strange that I am the only one left in a town where pasta was born,” he says. “I suppose I am the last of the Arabs, even though I am Sicilian,” he smiles.

|

| Tom Verde |

| Matteo barbera’s café in Trabia, Sicily advertises its pasta fresca (fresh pasta made with egg) as a take-out item to cook at home. |

|

Al-Idrisi’s description indicates a thriving industry and an expansive trade network that, by the 14th century, stretched north to Genoa and beyond. The earliest known document in Italian that clearly mentions pasta is the will of a Genoese soldier, Ponzio Bastone, notarized in 1279, that lists among his possessions a “barixella una plena maccaronis” (“a chest full of macaroni”). This must have been pasta secca, as only dried pasta could be stored and preserved in a wooden chest. The 13th-century Andalusian author Ibn Razin al-Tujibi, in his book Fadalat al-Khiwan fi Tayyibat al-Ta‘am wa’l-Alwan (Delights of the Table and the Best Types of Dishes) describes various types of pasta used in the western part of the Islamic world, including a recipe for pasta fresca to be used in a pinch when the dried variety “is not available,” indicating a commodity more commonly purchased in the marketplace—hence imported.

Pasta was also by then a food of poetry and potentates. Tuscany’s Giovanni Boccacio, in his classic 14th-century allegorical poem The Decameron, described a fairy-tale landscape with a “mountain made entirely of grated Parmesan cheese,” inhabited by people “who do nothing else but make maccheroni and ravioli, cook them in capon broth, and then throw them down the slopes.”

In the kitchens of England’s King Richard ii, the master chefs took a more down-to-earth approach to pasta presentation, which nonetheless included plenty of grated cheese as the classic accompaniment. The anonymous English author of the 14th-century royal cookbook The Forme of Cury advised, “Take and make a thynne foyle [sheet] of dowh [dough], and kerve it in pieces, and cast [t]hem on boillyng water and seethe it wele. Take cheese and grate it, and butter, and cast bynethen [beneath], and above as losyns, and serve forth.” The “losyns” was essentially lasagna, and while the book’s recipe for losyns called for the use of bread flour as opposed to durum (and thus seems to indicate pasta fresca) it does state that an important step is to “drye it harde” before cooking—which can be done only with durum flour.

(Some scholars have attempted to link losyns, and thus lasgana, to the medieval Arab-Persian term lawzinaj, a sheet cake made with almonds, sugar and rose water using both hard and soft wheat. Like many Arab sweets, the cake was typically cut into diamond-shaped pieces. The late Orientalist Maxime Rodinson saw connections between these confections and the French word for the similarly shaped heraldic design losange, from which the English word lozenge is derived.)

These and other such references to pasta in medieval Europe indicate a commodity that was both valuable and expensive, something that was typically imported, not readily available locally.

|

| Museo di Storia della Fotografia Fratelli Alinari / Brigdeman Art Library |

| Pasta dries in the sun in this photo dating from 1900 in Naples, where pasta was often called tria, a term that may come from itria, the word for long strands of dried dough known in the Levant since the fifth century. |

“It was a product linked to ports and trade, not something that was produced internally,” according to Alberto Capatti, co-author of Italian Cuisine: A Cultural History and a faculty member at the University of Gastronomic Sciences south of Turin. In fact, Capatti points out, pasta production in the Italian peninsula was not really widespread until the 19th century and the onset of the industrial revolution. (Growing up in the northern Italian region of Lombardy, Capatti noted that risotto—rice—was standard fare at the dinner table, not pasta.) Up until then, pasta manufacturing and consumption were more commonly associated with southern Italy: Naples, Apuglia and, most famously, Sicily, which Capatti considers the likely birthplace of Italy’s pasta industry.

But were Arabs, in fact, its parents? When al-Idrisi wrote of Sicily’s thriving pasta industry, was he referring to one that existed before the Arabs arrived, or the one that, as legend has it, came ashore with Asad ibn al-Furat’s warships? Thumbing through the pages of some of the earliest cookbooks offers more clues.

Just as there was no mention of pasta secca on Italian soil prior to al-Idrisi, there was also nothing much resembling a cookbook in Europe between the time of Apicius and the 13th century. By contrast, cookbooks in the Arab world emerged in Abbasid Baghdad, during the 10th century, perhaps earlier. There are, in fact, “more cookbooks in Arabic from before 1400 than in the rest of the world’s languages put together,” claims food historian Lilia Zaouali, author of Medieval Cuisine of the Islamic World. Usually bearing the same generic title—kitab al-tibakh, or “book of dishes”—these books were more readily known by association with their authors, much like those by today’s celebrity cooks.

The earliest known Arab cookbook—and the first to mention pasta—was compiled in the 10th century by an Abbasid court scribe named Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq. Derived from earlier eighth- and ninth-century recipe collections of caliphs and court officials, the book features a chapter on pasta, which here was called lakhsha, from the Persian word for “slippery.” (See sidebar, Who Called it Macaroni) It featured a colorful story of pasta’s invention during the reign of the Persian king Khosrau, who died in 579 ce.

|

“Italy is so close to us that you can smell the pizza,” jokes Tunisian guide Hatem Bourial. Indeed, the proximity of the Italian peninsula and Sicily to Tunis and other ports of this North African coastal nation have fostered centuries of cross-cultural exchange—including a diet that includes pasta. Tunisians are, in fact, the world’s third-largest consumers of pasta products, behind only Italy and Venezuela, respectively, according to the International Pasta Organization in Rome.

|

| Cindy Hopkins / Alamy |

“I’m not surprised at these statistics, because Tunisians consume pasta almost daily. It is very popular,” says Marinette Pendola, author of The Italians of Tunisia: The Story of a Community. The presence of Italians in Tunisia dates back as far as the 10th century, she wrote. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many Italians fled south to escape fascism, wars and poverty, establishing their communities in various urban centers.

With their taste for pasta, these Italian immigrants found kindred souls among North African Arabs who likewise enjoyed a wide variety of pasta dishes, as catalogued by food writer Clifford Wright in his exhaustively researched A Mediterranean Feast. Among those still popular today are:

Rishta: This is egg fettucine, often mixed with beans and vege-tables as an entrée or as a soup (rishta jariyya). It is also made with lentils in Syria and Lebanon.

Duwayda: This is Tunisian Arabic for vermicelli broken into inch-long pieces. When formed into little rings, they are identical to anelletti, the signature pasta of Sicily, which strongly suggests a cross-cultural exchange.

Hlalim, tlitlu and qat’a: These are small, grain-shaped soup pastas of various sizes, sometimes steamed, like couscous.

Muhammas: These small balls of pasta, sometimes classified as a kind of couscous, carry a name derived from the same Arabic word as hummus (chickpea dip)—hummais—which means “small garbanzo beans,” even though muhammas are closer to peppercorn size. Toasted granules of muhammas are sold in the us as moghrebiyya—a name that reflects their roots in the Maghrib—North Africa.

Eddeoueida: This kind of vermicelli is used among the nomadic Tuaregs of the Algerian Sahara, where it is also called talia—short for “Italia.” |

While out hunting on a chilly day, so it goes, Khosrau commanded his cook to whip up a nice hot pot of wild-ass soup. As an afterthought, the king suggested cooking “pieces of dough” in the broth. The delighted monarch “found it so delicious that for three consecutive days he wanted nothing else but this dish.” While this account is certainly folklore, al-Warraq’s book includes practical recipes for pasta dishes. These include Nabataean chicken, which calls for adding to the pot “three handfuls of itriya” and letting it simmer until cooked—a step that clearly points to pasta secca. It is also likely that early Arab pasta was small and grain- or rice-shaped, “like a coriander seed,” as one 13th-century Hispano-Muslim cookbook described it.

“It was made to imitate grain, and mainly used in broth,” says Sabban, pointing out that this shape also made it more portable by maximizing its density when packed.

Throughout the Middle Ages, as European scholars translated Arabic texts, they encountered these and many other books on dietetics and cuisine. One such work was the exhaustive Taqwim al-Sihha (Maintenance of Health) by Ibn Butlan, an 11th-century Christian physician from Baghdad. The book was translated into Latin in Palermo, at the court of Manfred, king of Sicily from 1258 to 1266. Later, in the 14th century, under its Latin title Tacuinum Sanitatis, a lavishly illustrated edition was published in Lombardy. Among the recipes was one for trij, or pasta, accompanied by a detailed image of two women making pasta—rolling dough and draping the long strands on a rack to dry, a method that remained largely unchanged into the early 20th century. (Click here to see illustration.)

Arab cuisine also added distinctive flavor to the earliest European text devoted specifically to Italian cuisine, the late 13th century Liber de Coquina (Book of Cooking). In addition to lasagna, the inclusion of several dishes with names and recipes derived from Arabic indicate that the book’s anonymous author may well have been transcribing recipes from an earlier Arabic text. These include romania (from rummaniya, or chicken with pomegranates); sumachia (from summaqiya, chicken with sumac and almond); and limonia (from laymuniya, meat with lemon).

In the 15th century, detailed recipes for pasta and pasta preparation appeared in Il Libro de Arte Coquinaria (Book on the Art of Cookery) by Maestro Martino of Como, dubbed Italy’s “prince of cooks” by Vatican librarian and fellow Renaissance humanist Bartolomeo Sacchi. Yet even here, in what is generally considered to be the first modern Italian cookbook, the author indirectly acknowledged the Arab roots of pasta by referring to sheets of pasta cut lengthwise into strings as triti (i.e., tria). The book also included a recipe for “Sicilian macaroni” made with flour, egg whites and rose water, an ingredient found rarely in the West but used commonly in high-end Arab and Persian cuisine. The inclusion of this costly, perfumed ingredient was further evidence of pasta secca’s value: Rose water was more likely found in a royal kitchen than a village one. Martino goes on to instruct the reader to cut the dough into long strips “the size of your palm and as thin as hay” and let them cure “under an August moon” when the air is warm and dry.

As delightful as this homemade pasta may sound, however, the common Renaissance manner of cooking it was almost abusive: Martino’s recipe concludes that “these macaroni should be simmered for two hours.”(Bartolomeo Sacchi disagreed on that point: In his own wildly popular De Honesta Voluptate et Valetudine [Respectable Pleasure and Good Health], the world’s first printed cookbook, published in 1475, he recommended that some pasta need only be cooked as long as it takes to say three Our Fathers, demonstrating the early Italian taste for pasta cooked al dente, a term which means, literally, “to the teeth.”)

“So the English and German way of overcooking pasta is not a mistake, but really the old way, according to Martino,” chuckles Andrea Gagnesi, cooking-school chef at Tuscany’s Badia a Coltibuono, founded by Italian cookbook author and instructor Lorenza de’ Medici. Another of Martino’s innovations, says Gagnesi, was eating boiled pasta with a fork, as it was too hot to handle with bare hands.

|

| Robert Landau / Alamy |

| A 1970’s roadside advertisement in Los Angeles shows pasta in its most common modern form: the family-sized, cellophane-wrapped bundle of spaghetti. |

Whether they prefer it well done or al dente, modern Italian food fans may find their beloved pasta easier to swallow than the idea of its possible Middle Eastern origins. Still, there is considerable evidence to indicate that the peoples of the Arab world played an essential role in the dissemination of pasta and pasta-making techniques in the West. This evidence also offers compelling answers to the three questions posed earlier: Durum wheat, pasta’s essential grain, was a common crop throughout the Arab world, from Mesopotamia to Syria, Egypt, North Africa and Muslim Sicily. Arab cookbooks were the first to mention forming semolina dough into dried, preserved shapes. And it was scholars writing in Jerusalem who provided the earliest known reference to cooking those shapes in water.

How is it that pasta, today so deeply identified with Italy, may have origins so far from Italian soil? Some food historians have suggested that the earliest pasta was an innovation of desert-dwelling nomadic Arabs, who relied on it as a handily portable food source. Others have questioned this hypothesis, pointing out that a regular supply of durum wheat, and the apparatus required to mill it, was beyond the capacities of nomads. Food writer Clifford Wright poses a compromise: Pasta secca may have made its way west with medieval Arab armies on the march across North Africa. It was, after all, a convenient and filling foodstuff and one easily transported, whether on camelback or, no less plausibly, in the holds of ships—some of which dropped anchor along the coast of Sicily some 12 centuries ago.

|

|

|

Paprika, relished for the flavor and color it adds to a recipe, is made by grinding dried peppers—sweet, hot or a combination of both. Peppers were New World crops introduced to Europe and the Middle East during Ottoman times. Paprika, depending on the variety of peppers used and whether the seeds were included in the grind, can range from a mild, sweet variety to one that will leave your eyes watering and your nose running. Hot varieties—not recommended for this dish—are usually marked as such or will list hot peppers in the ingredient list. Don’t be troubled by the large amount of paprika below. Four Tbs. is correct. Serves 4 to 6.

- ⅓ c. olive oil plus small amount to brush on serving dish

- 3 large onions, halved and sliced into thick slices

- 3 large cloves garlic, smashed and peeled

- Salt

- 4 Tbs. paprika

- 1 tsp. cumin

- 2 c. finely chopped canned tomatoes with juices, or 2 c. crushed tomatoes

- 12 oz. fettuccini or tagliatelle

- 1 c. unflavored yogurt at room temperature

Pour oil into a large sauté pan, add onions and garlic, season with salt, cover and cook over low heat for five minutes. Then uncover pan and continue to cook over low heat until onions are tender but resistant. Do not let them brown or caramelize. Lower the heat and quickly stir in paprika and cumin. Cook for a minute to release flavors. Keep the heat very low and stir constantly so paprika does not turn bitter. Pour in tomatoes, season with salt and simmer for 10 minutes.

Meanwhile, brush a serving dish with enough oil to coat the surface. Beat the yogurt with a pinch of salt. Cook pasta in boiling salted water until tender. Drain, transfer to serving dish, and pour the onions on the pasta. Toss in the yogurt or, alternatively, serve the yogurt separately.

|

|

|

Arab cooks once disdained eggplant for its bitterness. By the 10th century, they embraced a method, mentioned in Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq’s cookbook, of salting the vegetable before cooking, which draws out the bitter juices. This recipe reflects both the bounty of southern Italy—peppers, tomatoes, anchovies—and the culinary gifts the Arabs brought there: eggplant, spices and particularly the combination of sweet and savory flavors. Serves 6 to 8.

- 2 medium eggplants, washed and trimmed but not peeled

- ½ c. plus 3 Tbs. olive oil

- 3 large cloves garlic, chopped

- Salt

- 2 lbs. fresh tomatoes, peeled and chopped, or one 28-ounce can Italian plum tomatoes, drained and chopped

- 2 yellow or red peppers, cut into 1-inch squares

- ¼ to ½ tsp. red pepper flakes

- 1 tsp. cinnamon

- 6 to 8 anchovy fillets, rinsed if packed in salt, chopped

- ½ c. raisins

- 1 Tbs. capers, rinsed

- 1 lb. vermicelli

Cut eggplant into ½-inch cubes and layer in colander, salting each layer. Put a plate and a weight on top and let drain 1 hour. Rinse and squeeze gently with paper towels to dry.

Put ½ cup oil and garlic into a large sauté pan and cook over low heat until garlic is translucent. Add eggplant to pan and cook over medium-high heat until golden. Add remaining oil to the pan, and then stir in tomatoes and peppers. Season lightly with salt, add red pepper and cinnamon, cover and simmer for 15 minutes.

Stir in anchovies, capers and raisins, re-cover and simmer 15 minutes more.

Cook vermicelli in large amount of salted boiling water until tender, then drain and toss into pan with vegetables. |

|

|

Many people are familiar with pesto alla Genovese, but not so many realize that many other regions of Italy also have their own traditional recipes for pesto. Pesto alla Trapanese, a classic recipe from the western Sicilian port of Trapani, owes the introduction of almonds, replacing the pine nuts in the Genovese version, to Arab influence. The classic Trapanese recipe uses basil and tomatoes, but I like this modern variation, which also bows to Arab cuisine with the use of mint and cilantro. Serves 4 to 6.

- Sauce

- 1 c. packed fresh mint leaves

- ½ c. packed flat-leaf parsley, stems removed

- ¼ c. packed cilantro leaves

- ½ c. unsalted, blanched almonds

- 2 large cloves garlic, peeled and halved, with pale-green areas removed

- 1 tsp. ground coriander seed

- Salt

- 2 tsp. lemon juice

- ½ c. olive oil

- 12 oz. vermicelli or thin spaghetti (spaghettini)

- Topping

- 1 Tbs. olive oil

- ¼ c. shredded mint leaves

- ¼ c. raisins

- ¼ c. sliced almonds

- 3 Tbs. butter at room temperature

Wash mint and parsley and dry well. Put in the bowl of a food processor or blender and process until herbs are in small pieces. Add almonds, garlic, coriander and salt and process until almonds and herbs are very fine. With machine running, pour olive oil through the feed tube in a steady stream until well incorporated. Add the lemon juice. Transfer the sauce to a warm serving bowl.

Pour olive oil into small frying pan and, when it is hot, toss in the mint, al-monds and raisins. Cook, stirring and tossing constantly until almonds are lightly browned and raisins are plumped. Remove from heat and immediately swirl in the butter so it will melt.

Cook the pasta in boiling salted water until tender. Before draining, remove about 3 Tbs. of the boiling water and stir into the sauce. Drain and transfer pasta to serving bowl. Sprinkle on topping. |

|

|

Freelance writer Tom Verde, a frequent contributor to Saudi Aramco World, holds a master’s degree in Islamic studies and Christian-Muslim relations. Over the years, he and his sister, Nancy Verde Barr, have collaborated on many writing projects, not to mention homemade pasta dinners. |

|

Nancy Verde Barr is a culinary writer and has authored numerous books, including three award-winning cookbooks: We Called It Macaroni (Knopf, 1991), In Julia’s Kitchen with Master Chefs, with Julia Child (Knopf, 1995) and Make It Italian (Knopf, 2002). Barr has published numerous articles in Gourmet, Food and Wine, Bon Appétit, Cook’s Magazine and Fine Cooking. She is Tom Verde’s sister. |