|

|

|

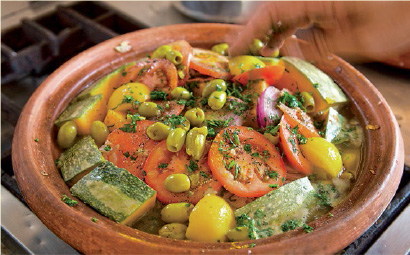

| Freshly harvested Crocus sativus blossoms are ready to have their trio of precious stigmas removed. They are saffron, which is used widely in such typical Moroccan dishes as this vegetable tagine. |

|

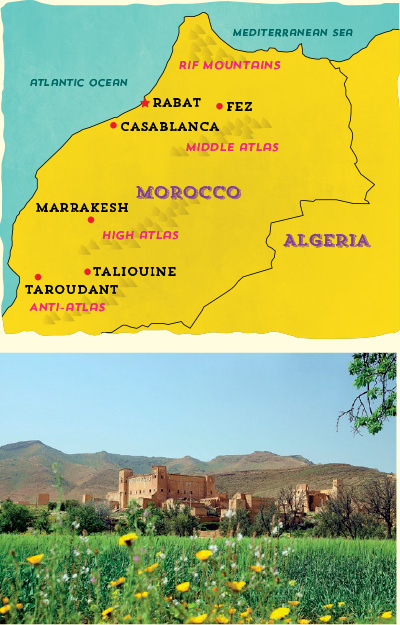

The village of Taliouine sits along a rock-strewn dry riverbed on the arid Souktana Plateau of Morocco’s Anti-Atlas range, about an hour and a half east of the majestic walled city of Taroudant. It’s a treeless, undulating landscape jagged with eroded, mineral-rich hills etched in geological whorls like fingerprints. Here and there in the distance, a white minaret juts up from a compact village and, on certain ridgelines, the crumbled ruins of an old citadel can be spotted. In autumn, the sun falls early behind the hills and, at some 1200 meters (4000') altitude, the late afternoon quickly turns chilly. The sporadic patchwork of fields in the hills around town looks tilled but unplanted in the fading light.

et for a few short weeks each year, morning reveals an altogether different scene. Scattered on the brown, hoed fields are lilac-colored Crocus sativus flowers that have bloomed—mysteriously, miraculously—during the night. Tucked within the delicate petals of each of these solitary flowers are three precious, thread-like red stigmas: saffron!

et for a few short weeks each year, morning reveals an altogether different scene. Scattered on the brown, hoed fields are lilac-colored Crocus sativus flowers that have bloomed—mysteriously, miraculously—during the night. Tucked within the delicate petals of each of these solitary flowers are three precious, thread-like red stigmas: saffron!

Each of those mornings, in the first hours of the day, workers—women mostly—pick the flowers before the petals can open and expose the precious threads to the sun, which wilts them and diminishes their color and aroma.

The short, intense harvest around Taliouine begins at the end of October some 15 miles east of the town and another 1500 meters (5000') up the mountain, and gradually works its way down to Taliouine proper, where the fields are the last to flower. The entire harvest lasts about one month, though only 10 days to two weeks in any particularly field. (Sometimes, in years when the climate is uncooperative, it is even shorter.)

Two thousand years ago, Pliny the Elder wrote in his Natural History, “There is nothing so much adulterated as saffron.” The same is true today. Saffron remains the most tampered-with or falsified spice in the market, cut or replaced with everything from safflower petals and dyed coconut fibers to turmeric, in the case of the ground version. The most important element in purchasing saffron is to buy from a trusted source. I recommend threads rather than ground saffron because they are more difficult to adulterate. Look for ones that are bright red to reddish-purple, long, and unbroken. |

In the last decade, saffron production has spread to other areas in Morocco: the Ourika Valley on the western slopes of the High Atlas not far from Marrakesh; Sefrou and Imouzzer Kandar in an apple-rich region of the Middle Atlas south of Fez; Chefchaouen in the Rif Mountains; and Debdou in the northeast. These disparate locations use bulbs from Taliouine and account for just a couple percent of the country’s total crop.

Taliouine (population 5000) remains the capital and heart of Morocco’s saffron industry. The rich volcanic soil here has excellent drainage, which is important for the health of the bulbs, and an ideal climate—dry, with brutally hot summers and cold winters—to give the saffron its potency, color and exceptional aroma. Saffron is deeply embedded in the local Berber culture, and centuries of honed agricultural skills have given locals the know-how to produce some of the world’s finest threads.

There are nearly three dozen cooperatives in the area, with the oldest and largest in Taliouine itself, the Cooperative Souktana du Safran. Founded in 1979, its 154 members own some 1098 hectares of land (2712 acres), with 275 hectares (680 acres) dedicated to saffron. (Local farmers also cultivate almonds, olives, vegetables and aromatic herbs.) During the 2012 harvest, these fields produced 300 kilograms (660 lbs) of dried saffron, according to the cooperative’s Zahra Tafraoui. Overall, she says, Taliouine produced 4000 kilos, or 98 percent of Morocco’s total. While the year was not considered a good one—it rained during the harvest—that amount still makes Morocco the fourth-largest producer of saffron in the world. Perhaps surprisingly, Taliouine now produces more than three times the amount of Spain.

ow did saffron come to this isolated place? “We have many legends,” Tafraoui tells me with a smile, “but few verifiable details.” The first written reference to saffron in Taliouine goes back only about 240 years, when zaafrane is mentioned three times in a contract dated 1776. But local historians say that saffron was being stored in a large, clifftop agadir (granary) less than 16 kilometers (10 mi) from Taliouine some 500 years ago, along with barley, oil and sugar.

ow did saffron come to this isolated place? “We have many legends,” Tafraoui tells me with a smile, “but few verifiable details.” The first written reference to saffron in Taliouine goes back only about 240 years, when zaafrane is mentioned three times in a contract dated 1776. But local historians say that saffron was being stored in a large, clifftop agadir (granary) less than 16 kilometers (10 mi) from Taliouine some 500 years ago, along with barley, oil and sugar.

Saffron most likely arrived in Morocco well before that, though, at least as far back as the ninth century, brought in stages on its long journey from Greece or Asia Minor, where it originated.

|

| tomas stankiewicz / look die bildagentur der fotografen gmbh / alamy |

| The old citadel of Taliouine, population 5000 and center of Morocco’s saffron industry, rises over a planted field. |

Ancient civilizations like the Egyptians and Sumerians appreciated saffron. It appears in the Old Testament of the Bible among the most sought-after aromas. “Spikenard and saffron; calamus and cinnamon, with all trees of frankincense; myrrh and aloes, with all the chief spices,” hymns a love verse in the Song of Solomon. Cleopatra supposedly washed her face with a saffron infusion to enhance her beauty and prevent blemishes, and to make herself more attractive. The ancient Greeks and Romans used it to dye hair and fingernails, as a perfume and to sprinkle around theaters for its fine, refreshing scent. In Natural History, a 37-volume work published around 77 ce, Pliny the Elder writes that the most esteemed saffron came from Cilicia, the kingdom located on today’s southeastern Turkish coast, and speaks of blending it with sweet wine. In his recipe collection De Re Coquinaria, the Roman cookery writer Apicius likewise adds it to wine, and uses it in sauces for boar, offal and various fish dishes.

Arab traders introduced saffron to Spain around 900 ce, according to Ian Hemphill’s 500-page Spice Notes, and Crusaders returning from Asia Minor with bulbs perhaps brought it to Italy, France and Germany in the 13th century. A century later, it was being cultivated in the English region of Essex. During the reign of Henry viii (1509–1547), it brought great wealth to parts of the country, including the well-known saffron-producing town of Chypping Walden, whose name Henry changed to Saffron Walden in 1514. During Henry’s rule, those who adulterated the spice could be put to death. (In Germany, they were burned at the stake.) Cultivation in England lasted 400 years before fading away.

|

| Though Taliouin’s saffron harvest often lasts about a month, beginning in late October, each field is picked within a period of a week to ten days. Inside the blossom, the three long, orange-red stigmas are saffron; the shorter, yellow pistils bear pollen—though the plant has been domesticated so long that it can no longer reproduce without human help. Harvesting and picking is most frequently done by women. |

Spain was for centuries the world’s leading producer. No longer. Today, Iran produces a dominant 96 percent of the global harvest. According to The Crocus Bank, a project supported by the European Commission, Spain had around 6000 hectares (15,000 acres) of saffron fields to Iran’s 3000 in the 1970’s; in 2005, there were just 83 hectares of saffron plantings, statistics from Spain’s Ministry of Agriculture show, though that number has approximately doubled in more recent years.

|

| Saffron can be removed only by hand, by pinching the bottom of the blossom and gently extracting the stigmas. Some 140,000 to 150,000 flowers are required to produce one kilogram (2.2 lbs) of saffron. Petals and pistils are discarded. |

Saffron cultivation in Iran, meanwhile, has skyrocketed to 50,000 hectares (123,500 acres). The Iranian Fars News Service reported in early 2013 that the country was producing 250 tons of the red gold annually and had set a goal of 500 tons by 2021. Iran exports to over 40 countries, including bulk quantities to Spain. It’s big business: According to Fars, saffron accounts for about 13.5 percent of Iran’s non-oil exports.

Making up the remaining global saffron production are the Kashmir region of India, the world’s second largest producer (mostly for domestic consumption), followed by the western Macedonian region of Greece, and then Morocco, Spain, Italy and Turkey. A handful of other countries also produce small amounts.

“The use of [saffron] ought to be moderate and reasonable, for when the dose is too large, it produces a heaviness of the head and sleepiness,” warns Culpeper’s 1649 Complete Herbal. “Some have fallen into an immoderate convulsive laughter which ended in death.” While I wouldn’t go that far, saffron’s potency does need to be respected while cooking. Only a pinch or two—10 to 20 threads—is required for most dishes.

Before adding, though, in order to fully maximize their flavor and color, the threads should be either dry-toasted and crushed, or else steeped in warm liquid.

To dry-toast, heat a small ungreased skillet over medium-low heat, add the saffron threads, and toast for 2 to 3 minutes, or until the threads have turned a shade darker in color and started to release their aroma. Place the toasted threads in a folded piece of paper and, with dry fingers, crumble them from the outside, and then shake the saffron from the paper into the dish. Alternatively, transfer the toasted threads from the skillet to a mortar, pound them into a powder, and add them to the dish. Swirl a touch of water around the mortar to get all of the crushed saffron.

To steep, place the threads in 120 ml / ½ cup hot water and infuse for 20 to 30 minutes. Incorporate the highly aromatic, brilliant golden liquid into the dish. Discard the threads or, if desired, use them in the dish. |

Prices are high. During the 2012 harvest, the Cooperative Souktana du Safran was selling 1 gram packages of saffron from their office for 32 Moroccan dirham (about $3), which translates to about $112 an ounce and $1800 per pound. Expensive, but a mere fraction of what consumers pay in Europe, the Middle East and North America—or even in the suqs of Marrakesh—for similar top-quality, unadulterated threads.

ultivating the world’s most expensive spice is laborious and time-consuming, and cannot be automated. According to local co-ops, about 90 percent of the production in Taliouine is done by small-hold farmers.

ultivating the world’s most expensive spice is laborious and time-consuming, and cannot be automated. According to local co-ops, about 90 percent of the production in Taliouine is done by small-hold farmers.

Planting takes place in Taliouine from the end of August through mid-September. Workers dig shallow furrows, place the onion-like bulbs (correctly called corms) about a short hand-span apart, and then cover them with earth. At the end of October, purple blossoms begin shooting up through the soil.

Just after dawn, women begin moving swiftly across the fields. Bent over at the waist and wrapped in colorful woolen scarves against the morning chill, they pinch blooms off at the base and place them in the wicker basket hooked over their other arm.

Once the baskets of blooms have been carried back to the family home and dumped out on a large table, the truly laborious and repetitive work begins.

Each flower has three bright-orange to reddish-purple stigmas—the female parts of the flowers—that are connected at the base of the bloom. Around 25 mm (1") in length, the stigmas are sharply pointed on the bottom end while the other flares out slightly. (There are also three short, yellow pollen-bearing stamens.)

|

| To make the most of saffron’s flavor, after extraction from the blossoms the threads are put out in the sun—or, less commonly in Morroco, on top of a low-heat oven—to dry to about 20 percent of their original moisture content. |

To remove the precious stigmas, pluckers pinch the bottom of the blossom and then nimbly extract the threads from the folds of the petals. The threads are set into a dish on the table while the petals and stamens are dropped to the floor. They pile up around the legs of the chairs, giving the room a heady floral, tropical aroma.

Like picking, the removing of the threads is mostly, though not exclusively, done by women. They spend the remainder of the long day (and often late into the night) around the table doing this easy but tedious work. Among the Ouhsoo family in the village of Ighri, where I experienced this past harvest, the hours pass in chatting, munching on local toasted almonds and sipping sweet, fragrant saffron tea.

To accentuate the flavor and aroma of saffron, the stigmas need to be dried, their moisture content reduced by about 80 percent. It takes around 140,000 to 150,000 flowers to make 1 kilo (2.2 lbs) of threads. In Morocco, drying is traditionally done by spreading out the saffron in the sun or inside a room, while Spanish producers put the stigmas in a drum sieve set on a stove. Open-air drying tends to give a spicier, stronger flavor to the threads while toasting over heat can bring out a deeper aroma. Recently, some Moroccan farmers have begun switching to the Spanish method. “But no more than one in 20,” Tafraoui tells me. For the moment at least, nearly all are sticking with the old way.

s befits its vagabond history and celebrated properties, saffron is the defining ingredient in a number of popular, even iconic, dishes across the globe. Saffron lends its golden hue and sweet-woody aromas to bouillabaisse in Marseille, saffron buns for St. Lucia’s Day in Sweden, saffron cakes around Cornwall and Pennsylvania Dutch chicken pot pie. It laces Indian ice cream and sweets, and, in Saudi Arabia, authentic Arab coffee is flavored with cardamom and often also saffron. But if saffron is queen of the spice-box, then rice is her most gallant consort: Northern Italian risotto alla milanese (Milan-style risotto with saffron), Spanish paella, Moghul biryani and Iranian polo all demand it.

s befits its vagabond history and celebrated properties, saffron is the defining ingredient in a number of popular, even iconic, dishes across the globe. Saffron lends its golden hue and sweet-woody aromas to bouillabaisse in Marseille, saffron buns for St. Lucia’s Day in Sweden, saffron cakes around Cornwall and Pennsylvania Dutch chicken pot pie. It laces Indian ice cream and sweets, and, in Saudi Arabia, authentic Arab coffee is flavored with cardamom and often also saffron. But if saffron is queen of the spice-box, then rice is her most gallant consort: Northern Italian risotto alla milanese (Milan-style risotto with saffron), Spanish paella, Moghul biryani and Iranian polo all demand it.

|

| Near Taliouine, a sign advertises saffron. Some 90 percent of the region’s saffron farms are small and family-owned. Much of the area’s marketing is done by some three dozen local cooperatives. |

In Morocco, cooks add a pinch of saffron to marinades and ground-meat kefta (meatballs), blend it with other spices in lamb, beef and chicken tagines (stews), and add it to cakes, especially during Ramadan. The country’s iconic spice blend, ras el hanout, always includes it.

It’s no surprise that saffron makes an even more frequent appearance in kitchens around Taliouine. Sometimes it’s as simple and unexpected as adding a pinch of crushed threads to a bowl of chopped fruit salad for dessert. For me, it reigns supreme in the unique local saffron tea, a winter favorite to prepare for guests.

Historically, though, saffron was valued foremost for purposes other than culinary ones. In Taliouine, women used saffron’s coloring agent like kohl to encircle their eyes. According to the displays at the Maison du Safran, an information center, laboratory and shop in Taliouine, this type of cosmetic use enhanced beauty as well as protected against evil. During weddings, designs were drawn on the faces of brides. Local artisans used it to dye wool for making carpets. In some southern towns, they used it to stain the cedar-wood ceilings.

Perhaps its most important use was in medicine, where it was used to treat ailments as varied as menopausal problems, depression and chronic diarrhea, and as an antidote for poison. In his authoritative Les plantes médicinales du Maroc (Medicinal Plants of Morocco), Abdelhaï Sijelmassi writes of saffron’s use as a stimulant, tonic and sedative. It whets the appetite, he reports, and can be a pain reliever for the mouth when ground into powder, mixed with honey and gently massaged into sore gums. Jamal Bellakhdar has similar advice in his Plantes médicinales au Maghreb et soins de base (Medicinal Plants of the Maghreb and Basic Care) and offers a saffron-syrup recipe for teething infants.

For centuries, Spain was the world’s largest and most reputed producer, with La Mancha, on the country’s high central plateau, producing what many cooks considered the best saffron in the world. But today little of it is actually Spanish. Spain’s El País newspaper reported that the country exported 190,000 kilos (418,000 lbs) in 2010, yet Spanish fields that year yielded just 1500 kilos (3300 lbs). This means that less than one percent of “Spanish” saffron sold was actually grown in Spain. The country imports the rest from Iran, Morocco and Greece, repackages it and then re-exports it.

True Spanish saffron is, of course, available. Read the fine print on the packaging or look for the official Denominación de Origen logo, a pen and ink drawing of Don Quixote on his horse in front of a lilac-colored flower rimmed on one side in red and yellow. The seal is a guarantee of authenticity—and quality. |

While Europe accounts for a shrinking fraction of global production, its saffron has prestige as well as legal protection. The European Union has awarded “appellation of origin” status to Greek “red saffron” called “Krokos Kozanis,” Italian “Zafferano dell’Aquila” and, most famously, “Azafrán de la Mancha” in Spain.

Recently, Taliouine has begun to actively promote its most famous product beyond Morocco’s borders. There is an autumn Saffron Festival, fair-trade certification and an alliance with Italian chefs. The Food and Agriculture Organization (fao) of the United Nations is working with groups such as Slow Food, as well as the local government, to give Taliouine’s saffron more geographic identity.

Tighter regulations mean a better guarantee of authenticity and thus quality. “The government of Morocco has developed its own legislation on appellation of origin and geographical indication,” Emilie Vandecandelaere of the fao explains, which “corresponds to the pdo [Protected Designation of Origin] in the European Union.” The 2008 law also introduced the slightly less stringent igp (Protected Geographic Indication) status as well. As of now, 25 of the 35 saffron cooperatives in Taliouine have been granted protected status.

|

| Spain, too, produces saffron, where it is a traditional ingredient in paella, the rice-based dish from Valencia, on the Mediterranean coast. Cooking paella over an open fire—carefully—toasts the rice at the bottom of the pan, lending the dish another of its essential flavors. |

The designation has helped push up the value of the local crop. In 2006, Taliouine’s saffron sold for just 8 dirhams per gram, compared to today’s 30 to 50. This is in part because of a global rise in prices but also partly a result of the pdo status, according to Lahcen Kenny, a professor at the Institut agronomique et vétérinaire Hassan ii in Agadir, Morocco. “But there was also a quite aggressive marketing strategy pushed forward by the grower associations and the regional council.”

The next step, says Vandecandelaere, “would be to request registration by the European Commission, so that their product could be also protected in the European Union member states.” This would give producers direct links to large distributors and retail stores, skipping the middlemen and keeping more profits locally. European-backed pdo would also be a powerful confirmation of the uniqueness of this product that is so deeply rooted in the land and traditions of Taliouine.

|

While mint tea is Morocco’s national drink, around Taliouine, saffron tea is a wintertime favorite, especially to serve to guests. It should be dark, sweet and aromatic. This method is that used by Mahfoud Mohiydine in one of the upstairs sitting rooms of Auberge du Safran on a late afternoon during the saffron harvest.

- Makes 1 pot; serves 4

- 10 saffron threads plus 1 or 2 more per glass for garnishing

- 1 Tbs loose-leaf gunpowder green tea

- 2 to 3 Tbs sugar

Crumble the 10 saffron threads into a heat-proof teapot or a saucepan and add 720 ml / 3 cups cold water. Bring the water to a boil, remove the pot from the heat, and let the saffron infuse and the water cool for 1 minute. Add the tea to the pot, place over low heat, and simmer for five minutes. Remove from the heat, and stir in the sugar.

Pour the tea back and forth between a glass and the teapot several times to blend. The color should be a dark, golden caramel color. Taste for sweetness and add more sugar if needed. Strain the tea into clear tea glasses, place a thread or two of saffron in each, and serve hot. |

|

This sophisticated tagine from La Maison Arabe in Marrakech, the city’s first boutique hotel and its finest kitchen, uses the trademark combination of sweet and savory, and draws on the riches of the citrus groves around Marrakech.

- Serves 4

- 1 tsp butter, softened

- 1 tsp ground ginger

- ½ tsp ras el hanout

- ½ tsp ground cinnamon

- ½ tsp turmeric

- ¼ tsp freshly ground white

pepper

- 1 generous pinch saffron

threads

- salt

- 2 Tbs olive oil

- 1 kg / 2 ¼ lb bone-in leg of lamb, cut into 8 or so pieces

- 1 small cinnamon stick, broken in half

- 1 medium red onion, finely chopped

- 2 Tbs fresh orange juice

- 1 tsp honey

- 1 Valencia orange, scrubbed

- 50 g / ¼ cup sugar

- 8 cloves

- 1 tsp toasted sesame seeds for garnishing

In a tagine, flameproof casserole, or large, heavy skillet, add the butter, ginger, ras el hanout, cinnamon, turmeric, white pepper and saffron. Season with salt. Moisten with the olive oil and blend well. One by one, place the pieces of lamb in the spice mixture and turn to coat. Add half of the cinnamon stick and scatter the onion across the top. Place the tagine over medium heat, cover and cook, turning the lamb from time to time, until the meat is browned and the onion is softened but not scorched, about 15 minutes. Add 240 ml / 1 cup water, loosely cover, and cook over medium-low heat for 45 minutes, stirring from time to time. Add 120 ml / ½ cup water and 1 Tbs of the orange juice and cook until the meat is tender, about 45 minutes. Add a bit more water if necessary to keep the sauce loose, or remove the lid to evaporate and thicken it. Stir in the honey and cook the lamb uncovered for a final 5 minutes.

Meanwhile, peel the orange, reserving the fruit. With a knife, scrape away some—but not all—of the white pith from the peel. Cut the peel into long, very thin strips about 3 mm / ⅛" wide. In a small pan, bring 120 ml / ½ cup water to a boil. Add the strips of peel and a pinch of salt, and simmer for 2 minutes. Drain, discard the liquid, and rinse out the pan. Return the strips to the pan, cover with 180 ml / ¾ cup water and bring to a boil. Stir in the sugar and add the remaining cinnamon stick and the cloves. Simmer until the liquid is syrupy and the strips of peel are tender but still al dente, about 20 minutes. Stir in the remaining 1 Tbs orange juice, remove from the heat and let cool.

With a sharp knife, cut away any white pith from the reserved orange. Carefully cut along the membranes separating the segments and remove them. Lay the segments in a shallow bowl, spoon the syrup from the pan over them, and let soak until ready to serve. To serve, divide the lamb among four plates, and top with the sauce, orange segments and strips of caramelized peel. Lightly sprinkle with the sesame seeds. |

|

Jeff Koehler (www.jeff-koehler.com) is a writer, traveler, photographer and cook. His work has appeared in many newspapers and magazines, and was selected for The Best Food Writing 2010. He is the author of four cookbooks, including Morocco: A Culinary Journey with Recipes. His new book is Spain: Recipes and Traditions. |