|

|

| Taking its name from al-qasbah (the fort) that overlooked the harbor, today the Casbah is home to some 80,000 people amid the 3.5 million who live throughout greater Algiers, the capital of Algeria. |

The Casbah of Algiers, spilling down the hillside to the Mediterranean coast, has been compared to Noah’s ark—teeming with life—and with the seeds in a pinecone—tightly enclosed. A nostalgic English sailor imprisoned within the walls of the whitewashed district 300 years ago recalled, “From the sea, it looks just like the topsail of a ship.” The 16th-century traveler Leo Africanus noted its many bakeries, while 600 years earlier the geographer Ibn Hawkal praised the limpid water pouring from its many fountains.

he site was inhabited as early as the sixth century bce by Phoenician traders, followed by Carthaginians who traded on the islands just offshore; then “various Berber tribes, Romans, Byzantines and Arabs (beginning in the seventh century ce) took turns coveting and ultimately taking the city,” notes the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (unesco). Periods of Spanish and Turkish authority followed, capped by 13 decades of French rule, beginning in 1830.

he site was inhabited as early as the sixth century bce by Phoenician traders, followed by Carthaginians who traded on the islands just offshore; then “various Berber tribes, Romans, Byzantines and Arabs (beginning in the seventh century ce) took turns coveting and ultimately taking the city,” notes the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (unesco). Periods of Spanish and Turkish authority followed, capped by 13 decades of French rule, beginning in 1830.

|

|

TOP: dea / a. dagli orti / getty images;

ABOVE: roger viollet / getty images |

| Above: Viewed from the sea in an engraving dated four years after the 1682 end of the last war between Algiers and England, the dense, trapezoidal, hillside Casbah could indeed appear “just like the topsail of a ship.” By 1880, top, the French had cut boulevards in what is known as the lower Casbah. |

The fort—al-qasaba—overlooking the quarter lends the area its name, even though it was once a place of gardens and palaces and now contains mostly the tumbledown homes of ordinary citizens. The French cut wide boulevards through the Casbah’s lower half after they arrived, and named its streets after their own people and places: Charlemagne, Chartres and the like. Meanwhile, Algiers expanded along the bay and a new European district filled up the territory next to the old town.

The Casbah thus forms the right ventricle of the city’s beating heart, through which flows the blood of the nation, and where—during the Algerian War of Independence—much of it was shed. Always a small and contested space at the center of Algeria’s history, it comprises some 60 hectares (150 ac) of densely built houses, laced through with 350 winding rues (streets), ruelles (alleys) and impasses (dead ends), which, if laid end to end, would add up to a 15-kilometer-long (9.3-mi) opportunity for getting terribly lost.

The Casbah’s population is reckoned at a tightly packed 80,000, within a city of more than 3.5 million residents.

Perhaps the most grandiose appraisal of the Casbah comes from the Englishman Samuel Purchas, who published travel accounts from around the world in the early 17th century. He called it “a Whirlepoole of these Seas, the Throne of Pyracie, the Sinke of Trade and the Stinke of Slavery … the Receptacle of Renegadoes of God and Traytors to their Country.”

|

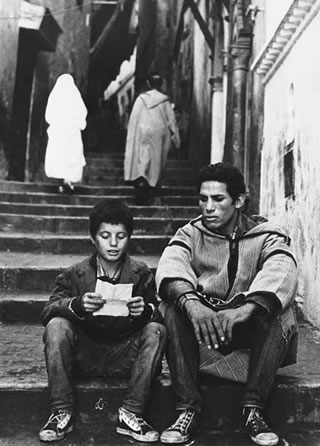

| “Too many people live here now with no memory of what came before, neither its culture nor its history,” says Zubir Mamou, 78. A resident of the Casbah nearly all his life, he often speaks to groups of visiting students. |

In a nutshell, it was a safe harbor on the shore of a turbulent sea; the home port of a corsair fleet, where Europeans, including Miguel de Cervantes—who made the remark about Noah’s ark—were imprisoned and held for ransom, but rarely enslaved and sold; and a place where some Christians “turned Turks,” as Shakespeare put it in Othello, and many fought against their own countrymen.

One of the more unusual captivity stories is that of the 15th-century Florentine painter Fra Filippo Lippi, who earned his freedom by painting his captor’s portrait. “One day, seeing that he was thrown much into contact with his master,” wrote Giorgio Vasari, the biographer of Italian artists, “there came the opportunity and the whim to make a portrait of him; whereupon, taking a piece of dead coal from the fire, with this he portrayed him at full length on a white wall in his Moorish costume. When this was reported to the master (for it appeared a miracle to them all, since drawing and painting were not known in these parts), it brought about his liberation from the chains in which he had been held for so long.”

For any given year throughout the 17th century, there were hundreds of European captives being held in Algiers, many kidnapped directly from their own coasts by corsairs. Historian Linda Colley suggests that the English Civil War of 1642 was partly caused by the unhappiness of the populace with the Stuart kings for not protecting Britain’s seaside. The dey of Algiers scolded Charles ii in 1672 for not buying his countrymen’s freedom, as the Spanish kings ransomed theirs. The final war between England and Algiers, between 1677 and 1682, resulted in 3000 hostages taken from 500 English ships.

For any given year throughout the 17th century, there were hundreds of European captives being held in Algiers, many kidnapped directly from their own coasts by corsairs. Historian Linda Colley suggests that the English Civil War of 1642 was partly caused by the unhappiness of the populace with the Stuart kings for not protecting Britain’s seaside. The dey of Algiers scolded Charles ii in 1672 for not buying his countrymen’s freedom, as the Spanish kings ransomed theirs. The final war between England and Algiers, between 1677 and 1682, resulted in 3000 hostages taken from 500 English ships.

Not the least of these was a Genoan sea captain named Piccinini, who converted to Islam in 1622, took the name Ali Bitchnine, married the daughter of a Berber sultan, became admiral of the corsair fleet and sponsored the construction of a mosque. Calling such a story a “whirlepoole” is scarcely an exaggeration.

|

| Using painted goal nets, boys play in a small plaza as a woman descends one of the stone-paved streets in the upper Casbah, where the steepest street has 472 steps. |

Troubles between Algiers and European powers—as well as America—over the predations of the privateers based there lasted into the early 1800’s. In 1816, an Anglo–Dutch fleet bombarded the city and extracted a pledge from the dey to rein in the privateers.

The construction of the Casbah’s perimeter walls and gates, including the western Bab al-Oued and the eastern Bab Azzoun, began in the early 16th century when Baba Aruj (“old man Aruj”) and his brother Khayr al-Din, Turkish pirates from the Aegean island of Lesbos, were invited by the amir of Algiers to evict his Spanish occupiers. When the one-armed Baba Aruj died in battle in 1518, Khayr al-Din took control, putting both the city and its corsair fleet at least nominally under the Ottoman aegis.

Khayr al-Din later became the top admiral of the Ottoman navy and the scourge of European sailors, who had misheard the name Baba Aruj and dubbed both him and his brother “Barbarousse” in French and “Barbarossa” in Italian—or “Red Beard” in English. Khayr al-Din’s statue, standing just outside the Casbah walls near a notorious French prison that used to bear his name, is now the butt of misplaced mockery: It shows him with both arms, but to Casbah residents, just as to the French, one Barbarousse is much like another, so they say he has one arm too many.

|

|

| Left: To architect Houria Bouhired—whose first name means freedom, and whose family was instrumental in the Algerian war for independence from 1954 to 1962—the Casbah itself “represented freedom, a place I could play on the terraces, hide in the alleyways and learn to be myself. And, I thought, if a town plan can make me feel that way, then of course I want to be an urban planner.” Right: Inside her house, false walls and this air vent connect to a hiding place used by liberation leader Ali la Pointe. |

oday, when architect Houria Bouhired leads a tour through the streets of the quarter where she grew up, she often starts in the Haute Casbah and descends the 472 steps of the Rue de la Casbah, which drops straight from top to bottom. Houria means “freedom” in Arabic, and her name was not a random choice, for she comes from a family of great Casbah patriots who defied the French during the early years of the war for independence (1954-1962).

oday, when architect Houria Bouhired leads a tour through the streets of the quarter where she grew up, she often starts in the Haute Casbah and descends the 472 steps of the Rue de la Casbah, which drops straight from top to bottom. Houria means “freedom” in Arabic, and her name was not a random choice, for she comes from a family of great Casbah patriots who defied the French during the early years of the war for independence (1954-1962).

French soldiers killed her father, Mustafa, and dumped his body on the ruelle where she played. As a 20-year-old militant, her cousin Djemila was arrested and condemned to death in a trial that made news around the world, though she was finally released. In 1958, while Djemila was still in prison, Egyptian director Youssef Chahine made the biographical film Jamila the Algerian about her case, which became a rallying cry for anti-colonialism.

The desire for freedom ran deep in the family: After being beaten and imprisoned, Houria’s mother, Fatiha, won fame for coolly playing a double game: She posed as an informer while brazenly harboring Saadi Yacef, leader of the Algiers military wing of the fln (National Liberation Front), and Ali la Pointe, Yacef’s chief Casbah operative, in her house on Rue de Caton. La Pointe is the hero in Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo’s prizewinning 1966 film The Battle of Algiers.

In Yacef’s memoirs of the Battle of Algiers, he calls his 12-year-old nephew—who served as a lookout and who died at Ali’s side—not “Petit Omar,” as he is called both in the film and on the portrait wall at the Place des Martyrs, but rather simply très jeune, very young. Houria remembers Omar not only as a heroic child but also as an expert player of marbles and other street games.

“I became an architect for a simple reason—because of the Casbah of my childhood,” she says, in a similar vein. “It represented freedom, a place I could play on the terraces, hide in the alleyways and learn to be myself. And, I thought, if a town plan can make me feel that way, then of course I want to be an urban planner.”

|

|

| The Casbah “has a future because it has a past, and we must fight to hold onto our past simply in order to move forward,” says native son Belkacem Babaci (top), president of Fondation Casbah, which provides social services and repairs for homes, roads, plumbing and more. Above: On a street outside the Casbah’s old walls, across from what was once a French prison, stands a statue of Khayr al-Din, the Turkish pirate who, at the invitation of the amir of Algiers, drove out the Spanish in the early 16th century. |

Houria’s sense of physical freedom echoes in the words of Cervantes’s friend and fellow captive Antonio de Sosa, who likened the Casbah to a pinecone and wrote in his 1612 account, Topography of Algiers, that it was “so dense and the houses so close that … one could almost walk the whole city via the rooftops.” In the “Captive’s Tale” chapter of Don Quixote, based on Cervantes’s own memory of the place, he describes “the windows of the house of a rich and important Moor, which, as is usual in Moorish houses, were more like loopholes than windows, and even so were covered by thick and close lattices.”

The Bouhired family home fits that description, and has an interior patio—the wasat al-dar, or center of the house—surrounded by three upper galleries, all tile-encrusted and horseshoe-arched, and a flat roof. It is also something of a shrine. A sign at the front door says it all: “The House of Shahid [“martyr”] Mustafa Bouhired, Restored in Memory of the November 1954 Martyrs.” A false wall over the stairs gives access to Ali la Pointe’s hiding place. An air vent in the bedroom of Houria’s tenant Zubir Mamu, a jaunty 78-year-old who has lived in the Casbah nearly all his life, connects to it. “I cannot help but think of him whenever I look there,” he says.

|

On the site where, in 1957, French paratroopers blew up the house on Rue de Caton, killing Ali la Pointe and more than a dozen companions, there now stands a memorial with the Algerian flag and memorabilia. |

|

| KOBAL / ART RESOURCE |

| Played by Brahim Haggiag in a scene from the 1966 classic film The Battle of Algiers, Ali la Pointe listens to the young cousin of rebel leader Saadi Yacef. |

Mamu’s own house on Rue de Lyon is now, as he sadly says, disparu (“disappeared”), and the Cinema Étoile of his youth is fermé (“closed”). On Rue Bleu he passes the former home, now abandoned, of the late Mostefa Lacheraf, author of the study of Algerian nationalism L’Algérie—Nation et Société, in which he called the Casbah a monde aboli, an “abolished world.” “The Casbah,” says Mamu, “is not as it once was. Too many people live here now with no memory of what came before, neither its culture nor its history, nor of what happened here at independence and during our struggle.”

The fact that Mamu calls the Casbah’s streets by their French names indicates a generational gap. When the French arrived, the streets were known simply by a nearby landmark like a well, gate or market, so they painted colored lines along the exterior walls to help them trace their way through its maze; Mamu knows the streets by their French color names. After independence, the streets were renamed in honor of Algerian heroes, many of them killed on those very walkways. Plaques mark those locations, such as the one on Rue Rachid Khabash where Abdel Rahman Arbaji was shot on the roof and fell to his death outside the door of number 39.

At Bir Djebah, “the well of the beekeeper,” one of the six public fountains still operating in the Casbah—there were once more than 150—a plaque commemorates four brothers in arms Touati Said, Radi Hmida, Rahal Boualem and Bellamine Mohamed. “Condemned to Death,” it reads with grave precision, “Guillotined at Dawn June 20, 1957 between 3:25 and 3:28 in the Morning at Barbarousse Prison.”

The prison has a special place in the memory of Lounis Aït Aoudia, president of a cultural-revitalization group called the Friends of the Rampe Louni Arezki. (Rampe is the French word for a steeply pitched street, and Louni Arezki is the name of another guillotined freedom fighter.) “As a child, my bedroom window was just below the prison walls,” remembers Aït Aoudia. “On days when an execution was to take place, I would wake up before dawn to the raised voices of the prisoners. They would sing our freedom anthem, ‘From our mountain, the voice of liberty is rising!’ My mother would cry, my father’s face would turn pale, and they would tell me to go back to sleep. But I heard that same song 90 times, for the 90 prisoners who were executed that year.”

Aït Aoudia recently brought another native son of the Casbah, Vienna-based economist Kader Benamara, author of the autobiography Éclats de soleil et d’amertume (Sparkles of Sun and Bitterness), back home for a book-reading. “Only 10 percent of the Casbah’s homes are occupied by their owners—all the other residents are squatters from the countryside,” says Benamara. “Our job is to teach them some history, teach them that the Casbah was a place of our nation’s new beginning, of its wealth and pride.”

Benamara was born in the cellar of 17 Rue Randon during the German aerial bombing of the joint American–British landing force of December 1942. Named for French general Jacques Louis Randon, who “pacified” Algeria’s mountainous Kabylie region on the coast in the 1850’s, it has since been renamed Rue Amar Ali, the real name of Ali la Pointe.

Benamara was born in the cellar of 17 Rue Randon during the German aerial bombing of the joint American–British landing force of December 1942. Named for French general Jacques Louis Randon, who “pacified” Algeria’s mountainous Kabylie region on the coast in the 1850’s, it has since been renamed Rue Amar Ali, the real name of Ali la Pointe.

“For a kid like me,” says Benamara, “the Casbah was a magical place day and night, a neighborhood of ordinary people, of flesh and bone, but also filled with the ghosts of everyone who had ever lived there. I can still see, as if I’m dreaming, the sweets seller pass through the streets, shouting loud enough to blow your head off: ‘My sweets will erase all your troubles!’ And we children would salivate as soon as we heard him.”

Perhaps no one works harder at the Casbah’s urban revival than Belkacem Babaci, president of the Fondation Casbah, which provides social services to residents and advocates for the repair of its infrastructure. If a house is in danger of falling down, or neighbors cannot agree to fix a plumbing leak in a common wall, they come to him. Babaci was born in the sumptuous Palais des Raïs, the seat of the Algerian admiralty and, formerly, of the Barbary corsairs. “My grandfather was a captain,” he says, “which entitled us to living quarters there. So I know how beautiful the Casbah’s architecture once was.

![Seven medallions, framed by floral and shell motifs, decorate a carved and painted panel above a doorway. The medallions on the panels flanking it repeat “[there is] no victor but God.”](images/casbah/MG_4204_sm.jpg) |

Seven medallions, framed by floral and shell motifs, decorate a carved and painted panel above a doorway. The medallions on the panels flanking it repeat “[there is] no victor but God.” |

|

| Where once some 150 public water fountains could be found, today only six still flow. |

“In 1830, before the French came, you could say that the city of Algiers was the Casbah. Now the Casbah is simply part of the city, just a little piece, in fact. What was once the citadel has grown to encompass everything—from the residential quarter up high to the modern city down below, where the French cut through to the seaside with wide arcades and commercial streets. They knocked down the city’s walls and gates, from Bab Azzoun to the east to Bab al-Oued to the west, and converted mosques into churches. Palaces were knocked down to create public plazas or turned into museums. The most prominent park in the Casbah—Place des Martyrs, named for our war heroes—was once the most beautiful palace in all Algiers.”

The Dar Mustafa Pasha calligraphy museum and the Dar Khedaoudj museum of popular arts and traditions, both restored to the sparkling gems that most private homes in the Casbah once were, help to knit the quarter’s history together. Aziza Aïcha Amamra, director of Dar Khedaoudj, was born in her mother’s house on the jabal—the mountain, as she calls it—in the Haute Casbah. A trained folklorist, she remembers the songs of Ramadan, sung when those fasting were awaiting the cannon’s signal for their first meal of the day: “Call, call us to prayer, oh Shaykh! The cannon has sounded its ‘boom boom!’” So I’m ready to eat! Yum yum!”

Belkacem Babaci’s childhood memories are not always so benign. “I remember the terrible discrimination of the French,” he says. “Regardless of my grades in French language class, which were always ‘superior,’ I had to sit behind even the laziest French student. The teachers couldn’t accept that an indigène, or native, as they called us, could speak more perfectly than one of their own—even though Algeria was supposedly an integral part of France, and we were theoretically its full citizens.”

|

| Boys play below the ruins of Ali la Pointe’s house, part of which has been left unrestored as a memorial to the sacrifices of independence. Among the Casbah’s other houses, today only 10 percent are occupied by their owners, says Fondation Casbah director Belkacem Babaci. |

Babaci notes that the Casbah residents would mock their French colonizers with dry humor. “Donkeys were our delivery boys and garbage haulers,” he remembers, “and just like bus drivers, they knew every house. We gave them satirical names—like Isabella and Ferdinand, the Spanish sovereigns who drove many of the Casbah’s first residents from Iberia in 1492, or Charles v, whose 500-ship navy failed so disastrously to take Algiers in 1541. So the donkey drivers would holler: ‘Turn left, Isabella, turn right, Charles.’”

Babaci says that the Algerian revolution’s aftermath—when some 10,000 residents left—as well as the civil strife of the 1990’s, shredded the Casbah’s social fabric. With irony, he notes what was once a prison for Europeans, and later, during the war of independence, a concentration camp run by the French, has now become the dead end of squatters. Nonetheless, he firmly believes that the Casbah “has a future because it has a past, and we must fight to hold onto our past simply in order to move forward.”

|

| Clockwise, from left: A girl poses against a column at her home. Outside the horseshoe arch that leads to his home, Miraoui Smain wears a chechia, the close-fitting Algerian cap of an older nationalist generation. “Many do not even know what my cap means. I was part of our freedom struggle," he says. Boys pose in the upper Casbah. Brass-smith Hachemi Benmira is holding onto his business selling trays and coffeepots despite the scarcity of visitors to the upper Casbah. |

Unesco calls the Casbah “a unique form of medina, or Islamic city,” highlighting its “considerable influence on town planning … in North Africa, Andalusia and sub-Saharan Africa” in the 16th and 17th centuries. In 1992, it placed the site on its World Heritage List, and in 2003 algeria designated the Casbah a protected sector, in light of what unesco calls the “continual need to forestall the deterioration of the urban fabric.” Lately, however, because of inattention, it has been threatened with decertification by the un body.

Zekagh Abdelwahab oversees the Algerian Ministry of Culture’s Plan to Protect the Casbah, which provides emergency repairs to houses in danger of collapse. Indeed, many structures today seem almost to be tent-pegged in an erect position, with jerry-rigged wooden timbers supporting leaning walls, cracked balconies overhanging the streets and sagging arches framing courtyard arcades.

Some 700 homes have already received Abdelwahab’s urgent attention. “The Casbah has been hit hard by many insults—everything from earthquake damage to stone foundations that dissolve because of leaking water pipes,” Abdelwahab says. “Most homes are occupied by tenants who refuse to leave during repair work, but our job is to work around them.” The consequences of neglect are ever-present: litter-strewn voids in the irregular urban grid where homes have collapsed—like empty sockets in a mouthful of crooked teeth.

Abdelwahab and his team of architects are especially chagrined by the almost haunting presence of the Centenary House in the Haute Casbah, a kind of artificial show house constructed by the French in 1930 from the bits and pieces of the many historic palaces and other homes that they had knocked down, or allowed to fall down, over the previous 100 years.

|

| Clockwise, from top left: Woodworker Khaled Mahiot’s lathe-turned, lattice window screens are so traditional they might feel familiar to Spanish author Miguel Cervantes, who was captive briefly in the Casbah in the 16th century. Along Rue Ben Chenab, the market street that divides the upper and lower Casbah, a young man sells oranges. Halim Ouaguenouni tends his family sweet shop that is adorned with decorative tiles and soccer-fan paraphernalia. A boy poses in front of a door that reflects the Casbah’s long history. |

It is not enough that woodworker Khaled Mahiout, who moved from the Basse Casbah to the Haute Casbah in search of lower rents, still ekes out a living by turning spindles on his lathe to make the same latticed window screens described by Cervantes, or that brass-smith Hashmi Benmira still holds onto his business of selling trays and coffeepots near the 11th-century minaret of Sidi Ramdane mosque. These upper precincts are not well trafficked, and certainly not by tourists.

Eighty-year-old Miraoui Smain stands outside his house on Rue Ben Chenab, which cuts east to west, separating the Haute Casbah from the Basse. He wears a chechia, the close-fitting Algerian cap of an older nationalist generation, a far cry from the T-shirts and backward-turned baseball caps of young people today. “What bothers me most about them is not that they are poor, but rather that they understand things poorly,” he says. “Many do not even know what my cap means. I was part of our freedom struggle; I was a witness to our attempt to rid the Casbah of its foreign vices. It is not a bad thing to go back to some things from the past.”

The Casbah’s steeply stepped view over the lower flank of Bouzaréah Hill, encircled by the remains of Ottoman-period walls and itself overlooked by a citadel that is similarly in need of repair, may not inspire confidence that our new century will be kind to this aging quarter. But what Antonio de Sosa wrote in 1612 is still true today: “Little by little this hill creeps upwards to the very top so that the houses keep rising on an uphill slope, the higher ones jutting over the lower...,”each one helping its neighbor remain standing, despite the downward pull of gravity and historical forgetfulness.

|

Louis Werner ([email protected]) is a writer and filmmaker living in New York City. |

|

Kevin Bubriski (www.kevinbubriski.com) is a documentary photographer and professor of photography at Green Mountain College in Poultney, Vermont. |