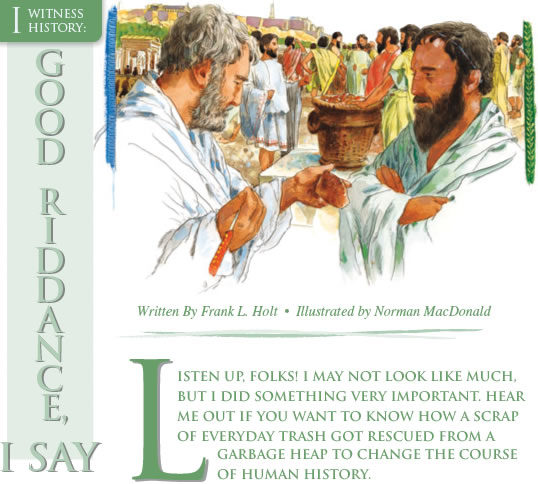

I come from what Greek folks call hoi polloi—the common people. Born in the potters’ quarter of Athens—still called Kerameikos (“Ceramicsville”) today—I grew up hard and fast. Only hours out of the kiln, I stood on a rough-hewn shelf, my mouth wide open in awe of my surroundings. Craftsmen of every description were spinning their creations. I listened to their colorful shoptalk and watched as their muddy fingers taught the clay to become fancy pots. Talented painters turned many of these into the masterpieces you see in museums today. Not me. I never got glazed or painted. Since nobody bothered to make me beautiful, I knew right away what to expect. I was the workaday ware of every kitchen and storeroom in bustling Athens, the kind that when broken, was mourned for a moment—but only because of what I spilled—and then immediately forgotten and replaced.

Shattered, I waited in the household trash for that last journey out to the bottom of some deep well or smelly garbage pile beyond the city. I passed my final days in idle trash-talk with other scraps of pottery. Some bits bragged of vases they had spotted in this fine shop; others put on airs about the jobs they had once had—preparing food for a wedding feast or funeral. Most of us, however, fantasized about one last chore before the grave. We wanted to become something called an ostracon, a piece of busted pot you could write on with something sharp. This was all the rage back then.

|

| Clay pots were in every ancient Greek kitchen—and the pieces of those that broke made a great jotting surface. |

Today, everyone uses paper, but in my day, paper (in the form of imported papyrus) was too pricey for the average Greek. In Athens, a grocery list on paper would have cost more than the groceries! That’s why Athenians sometimes fumbled through their trash to find shards of shattered crockery like me. On us, a Greek could scratch a useful line or two, just as you might do today on the back of an old envelope.

Scratched on me were only three and a half words, but those words saved what you folks now call Western Civilization. Think I’m joking? Let me finish my story.

You see, the Athenian house where I lived belonged to a registered citizen with the right to vote. He had no education, yet he attended the peoples’ assembly whenever he could. There he voted on everything having to do with how the government was run. Imagine that: a commoner in charge of war, strategy, finances, religion—you name it. He even helped make the laws! It seemed to me that he lived an exciting life where the people (actually, only the men) decided everything for themselves. He called it a democracy.

I remember moving into this man’s trash at a very scary time—not just for me, but for the whole city. Day after day my owner came home from the assembly and agora (the marketplace) with terrifying talk of a Persian invasion. Persia was the biggest power on Earth, and the Persians were unbelievably rich, powerful and angry—especially at Athens. They accused us of meddling in their affairs. Only eight years earlier, the Athenians had defeated the Persian army under King Darius at Marathon, but now, in the year you folks call 482 BC, we went on red alert. Darius’s son Xerxes was making plans to destroy Athens!

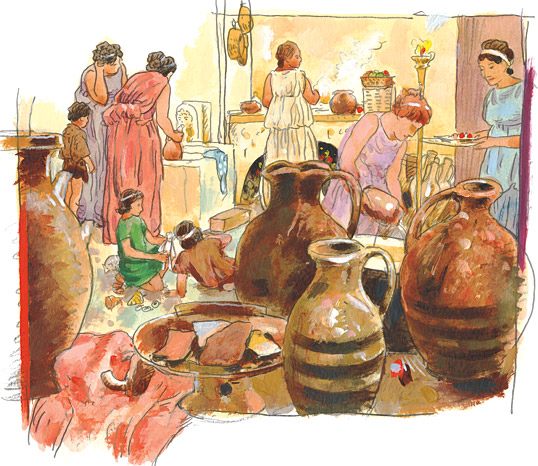

|

Aristeides wanted to divide the profits from the new silver finds among his fellow Athenians. |

But the news was not all bad. From my place in the kitchen trash, I overheard my owner crowing like a rooster that he was suddenly rich. Apparently, state workers had discovered a bonanza of pure silver. The find was worth a fortune. And a politician named Aristeides proposed that the city parcel out fair shares of the silver to every citizen. He was a Marathon hero and a leader so honest and wise that the people called him “Aristeides the Just.”

|

Themistocles wanted the silver money to go into the state treasury, to be used to build new warships. |

But this was democratic Athens, where even a no-brainer had to be debated. For days my owner fretted around the city, worried that some fool would come up with another scheme for the money. And sure enough, somebody did. A man named Themistocles proposed that, instead of keeping the money, the people should let him spend it on a bunch of warships. You should have heard my owner howl at the idea! Boats? Didn’t we already have a large fleet? And, if we did need more ships, didn’t our laws say that the wealthiest Athenians had to cover these expenses through special taxes?

Most citizens made fun of Themistocles, but the man simply would not keep quiet. My owner said it was “pure politics, nothing more.” Others dismissed his proposal as a sad outgrowth of the feud between Themistocles and Aristeides.

Then, one afternoon my owner came home wondering if Themistocles’s idea had merit. What if Athens could not defend itself with the ships it already had? How could even the rich cough up enough money to build hundreds more right away? Look at the big picture, my owner finally said. It was the patriotic duty of every good man to put aside self-interest and give up his share of the mining revenues for his country. Yes, here with me lived an uneducated man who could actually think for himself, and not just about himself. He wanted a free country more than free cash. I never felt prouder to be in his house.

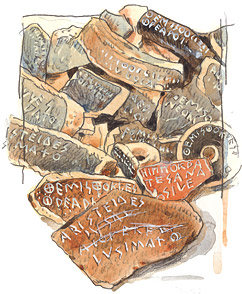

|

The ostracon in front represents the one in this story—with the scratched out lines following the letters that spell the name Aristeides. |

Soon after, my owner fished me from the garbage and used me to write down his vote in a special election. Not an election you would want to win, though, because if you did, you were ostracized and given 10 days to get lost. Every year, the Athenians could do this. They met each winter in the assembly and voted on whether to ostracize anyone. If they decided “yes,” they met in the spring to choose a “winner.” On that occasion, every registered citizen (like my owner) showed up at the agora with an ostracon. He then scratched the name of a person he wanted gone on his ostracon and pitched it into a pile to be counted. If at least 6000 people voted, then the guy with the most votes had to leave Athens for 10 years. He could then return to the city and pick up where he left off, no hard feelings.

Nobody’s name was off limits, and the fellow ostracized had no right to defend himself or appeal. The Athenians knew the system could be abused, but they felt a lot safer if they could defend their new democracy against dangerous individuals. An annoying neighbor would not get enough votes to be ostracized, but a stubborn leader who refused to compromise might. Good riddance, I say!

As you can imagine, supporters of both sides were working the crowd in the agora. My owner was clearly nervous. He could barely read or write, but had practiced writing the letters A-R-I-S-T-E-I-D-E-S and now did his best to scratch them correctly along the upper edge of his ballot. He was also supposed to write the name of Aristeides’s father, Lysimachus, to make sure people knew exactly who he meant. But he just couldn’t spell it. He needed help. Instead, he started to write the name of the district of Athens where Aristeides’s family was from, but he only got partway done.

|

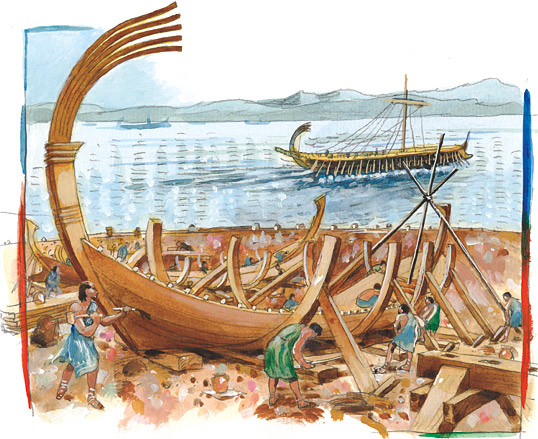

| “That’s it, men! Work as quickly as possible—but make sure the ship is the tightest and best built ever!” And so the shipwrights work feverishly to finish Themistocles’s new vessels. |

Other hoi polloi did as well. It was said that a poor voter asked a man he saw how to spell the name “Aristeides,” not realizing that the man he was asking was actually Aristeides. Without saying who he was, Aristeides helped the guy and then asked why he disliked Aristeides. “Never met him,” admitted the voter, “but I’m sick and tired of people calling him ‘The Just’ all the time.”

Something similar happened to my owner and me. When a fellow voter saw what was etched on me, he grabbed me and roughly crossed out everything but the first word, Aristeides. Then, he scratched the name Lysimachus straight across my lower edge and walked away.

I was done, tattooed with the three and a half words that tell the story of my incredible life. With a proud man’s determination and a stranger’s help, I made a difference. I counted in the historic vote that ostracized Aristeides. The deadlock over the silver was over. A few years later, it was indeed the warships that Themistocles built that saved Athens and its democracy from Xerxes’s troops. Otherwise, Western Civilization as you know it would never have existed.

Of course, I missed seeing most of the good I did. After I got rid of Aristeides, government workers buried me and a bunch of other ballots near the agora. We didn’t see daylight again for 2500 years. Archeologists finally dug us up and recognized right away who we were. I got my picture put in books, and, by golly—talk about luck!—I ended up in a museum, the Agora Museum. If only my swanky-vase cousins could see me now, the grubby poor kid from the Kerameikos who changed the world.

click here to view the original article

|

Frank L. Holt ([email protected]) is a professor of history at the University of Houston and most recently author of Into the Land of Bones: Alexander the Great in Afghanistan (2005) and Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions (2003), both published by the University of California Press. |

|

Norman MacDonald (www.macdonaldart.net) is a Canadian free-lance artist, living in Amsterdam, who specializes in history and portraiture. He painted salukis in Saudi Aramco World’s May/June 2008 issue; these are his first portraits of potsherds. |