|

| "Yes, that's right! I'm an Arabian leopard. But why have you entered my realm?" |

Activities

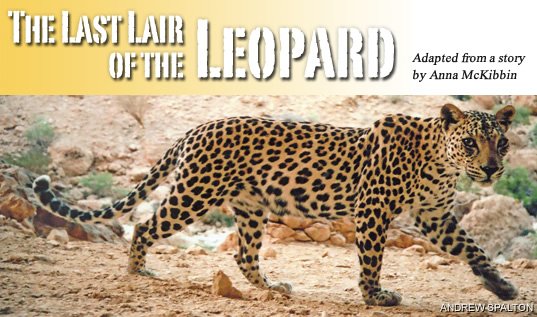

The

leopard emerges from beneath an overhanging rock in mountains of Dhofar in southern

Oman. Its pale coat blends in perfectly with the dusty background on the rugged

range of peaks known as Jabal Samhan. Positioning itself in front of a vertical

rock face, the leopard lifts its tail stiffly and sprays the rock with a

pungent calling card. Then it then sniffs the boulders for evidence of other

visitors and slinks off down the trail.

It's

hard to absorb the significance of what we've just seen, and perhaps even

harder to picture the Arabia of ancient times when sights like this were commonplace. The second-century bc Greek geographer and historian Agatharchides wrote, “The pasturage ... supports

flocks and herds of all sorts. Crowds of lions, wolves and leopards gather from

the desert, [and] against these the herdsmen are compelled to fight day and

night in defense of their flocks.”

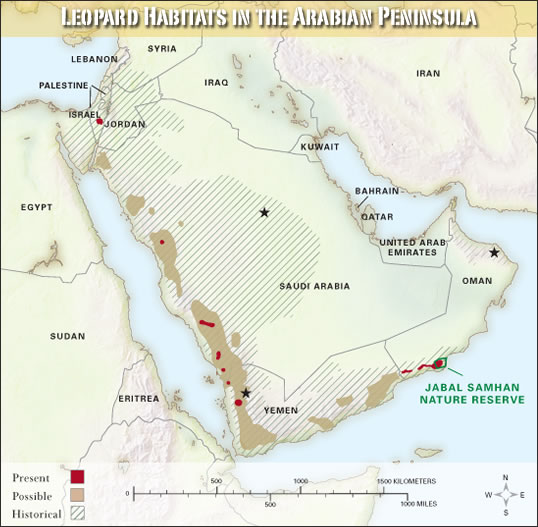

Today,

it's very different. The lions disappeared centuries ago, and the wolves are

few in number. But—somehow—the leopard managed to linger. Jabal Samhan, a

super-arid network of rocky plateaus and nearly impenetrable gullies

where June shade temperatures regularly top 46 degrees Centigrade (115°F), is

one of the last lairs of the elusive Arabian leopard.

Arabian Leopard Factfile

Scientific name: Panthera pardus nimr

Head and Body Length: 1.3 meters (4' 4")

Weight: Male 30 kilograms (66 lbs), female 20 kilograms (44 lbs)

Habitat: Mountainous areas with forest/scrub, preferably with permanent water sources

Prey: Gazelle, ibex, hyrax

Threats: Persecution, poaching, habitat loss, prey depletion

Behavior: Generally thought to be nocturnal, but this is now in question. Marks territory using scrapes, scent marking and defecation.

Unlike

Agatharchides, however, I still haven't seen an Arabian leopard in the wild.

Very few people have. What we viewed this morning was an image on a video

screen. The Arabian leopard is one of the rarest animals on the planet. Until

recently, no one knew for sure if the leopard still lived in the Dhofar

mountains. The only visible evidence of its continued survival had been the

occasional goat seized from a settlement on the edge of the territory, often followed

by the discovery of a leopard carcass bearing a lethal gunshot wound.

For

humans, the odds of a chance encounter with a leopard are almost zero. Not only

is the stealthy cat wary of humans, its coat is such that it blends in almost

seamlessly with its environment.

The

International Union for Conservation of Nature has classified the Arabian

leopard as “critically endangered,” meaning it faces an extremely high risk of

extinction. In 1976, Oman granted it special protection and in 1997 further

safeguards were enacted when an area of 4500 square kilometers (1740 sq mi)

comprising Jabal Samhan was declared a protected area. But, it was unclear

whether, by that time, it already had edged too far toward extinction. Unclear,

that is, until one man took up the challenge to find and photograph the animals.

|

| KHALID AL HIKMANI |

| "Steady there—we're almost finished!" says a researcher as he holds the head of a sedated leopard, fitted with a GPS collar. To trap this leopard and three others in 2001, the researchers use goats as bait. |

“It

started in 1989,” explains wildlife cameraman David Willis. “I was interested

in filming ibex and heard that in Jabal Samhan you could see herds of up to 40

animals. One night while camping we heard a leopard calling. I'd heard them

before in Africa but didn't think it was possible to encounter them in Oman.

Then, over the next few days, we saw the tracks.”

Willis

decided to try to photograph the animals. He used a homemade system of remote

35-mm cameras, installed in locations where he had found footprints, “scrapes”

made by pawing the ground and other leopard markings. Each camera was linked to

a carefully disguised pressure plate—a plywood platform that would trigger the

shutter when it was stepped on. Willis left the setup in the mountains and then

traveled some 1000 kilometers (620 mi) back to his home in Muscat, the capital

of Oman.

“When I recovered the film three months later and saw that 15 frames had been

shot, I assumed they would be pictures of dogs and donkeys—maybe the occasional

camel,” Willis explains. But when he had the film developed that he saw, among

the dogs and donkeys, eight pictures of an animal few had ever seen in the

wild: likely the first-ever images of the Arabian leopard.

Research Methods

Oman's Arabian Leopard Survey uses a variety of techniques to learn more about its subject:

Ground surveys: Researchers comb the area for signs of leopard presence. These include territorial scrapes, scats or urine, scent sprays and evidence of kills.

Camera trapping: A weatherproofed camera is positioned next to routes known to be used by leopards. The camera may be triggered either by a pressure plate or an infrared beam. Researchers can use the resulting images to identify individual leopards.

Satellite tagging: Leopards are trapped, sedated and fitted with collars carrying satellite tags. Although expensive, the collars can provide detailed information about the leopards' movements and behavior.

There's

no denying that the Arabian leopard is a magnificent beast. Its coat is a

creamy-buttermilk color, its rosettes (the technical name for the spots that

pepper its lean frame) an inky black. The combination makes it virtually

invisible in its rocky hideout. Although smaller than its African counterpart,

this is a powerful predator—though clearly not one averse to a little fun: One

series of shots shows a leopard in a variety of airborne poses, returning

repeatedly to bounce on the spring-loaded pressure plate.

After

hearing about Willis's work, Dr. Andrew Spalton, adviser for Conservation of

the Environment in Oman, immediately recognized its potential and the Arabian

Leopard Survey was born. “We suffered endless technical issues,” explains

Spalton. “Our equipment overheated, leopards scent-marked the cameras by

rubbing against them, donkeys knocked them over, and mice chewed through the

cables.” Even when the camera-traps worked, the results were less than

reliable. “Having mounted a major expedition to recover films and reset traps,

we could get entire films full of nothing but donkeys. From a total of 13

cameras, we might get one leopard image,” he says. Nonetheless, between 1997

and 2000, the team gathered a total of 251 photos of Arabian leopards.

To

count the number of leopards recorded on film, researchers used the shape and

pattern of the rosettes on each leopard's coat. These are unique to each animal,

rather like a human fingerprint. Analysis of the images revealed 17 individuals:

16 adults (nine females, five males and two of unknown sex) and, most exciting,

a cub. The results suggested a total population of around 50, confirmed that

the leopards were breeding and offered invaluable information about leopard

behavior.

|

| KHALID AL HIKMANI |

| "Believe me, saving the leopard will help your village and the area," says a Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve ranger. The goal is to persuade local residents that the benefits of keeping the leopards alive will outweigh the loss of livestock to the leopard. |

Leopards

are widely considered nocturnal animals. However, those in one of the three

monitoring areas were most active from six to nine in the morning and three to

seven in the evening. Spalton thinks that this could be due to the different

environmental conditions in this area, which includes a steep-sided gorge with

permanent water and plenty of shade.

But

a more important factor, he suggests, is the absence of human activity. Since

leopards avoid human contact, with none in the area, the leopard can adjust its

activities to suit environmental conditions.

In

2001, Spalton led the team on an even more ambitious project—satellite tagging.

Team members capture the animals and then sedate and fit each with a collar

carrying a small GPS device. The collars store data for three months and then

drop off. Despite some technical hitches, four collars have been recovered and

the data they contained reveal some astonishing information about the leopards'

movements. For example, some travel long distances. One covered 476 kilometers

(295 mi) in a 55-day period!

Such

distances are not difficult to explain. Data gathered by the survey team

suggest that male leopards in this area have an average annual home range of

180 square kilometers (70 sq mi), while leopards living in lush grasslands,

which support a higher concentration of prey, may have a range of 50 square

kilometers (19 sq mi) or less.

But

the leopard's need for food and the fact that it roams such a wide area have

brought it into conflict with another predator: humans—specifically, the

nomadic tribesmen of Jabal Samhan who keep camels in the hills. When the khareef,

the southwest monsoon, brings rains, the tribesmen bring their camels to the

lower pastures.

Hadi

al Hikmani, a member of a Jabal Samhan family, says, “In some ways my parents regarded the leopard as an enemy to be

feared, as it kills livestock. But if we heard the leopard calling when we sat

round our camp at night, everyone would get very excited. It was regarded as a

good omen. The older men said it would be a good year ahead.”

|

| ANDREW SPALTON |

| "Look. Here's a photo of one of our country's most prized treasures—the Arabian leopard." In Oman today, students learn that while leopards may at times be a nuisance, they are also an integral part of southern Oman's ecology. |

Today,

al Hikmani is employed full-time by the Arabian Leopard Survey. His job is to

help bridge the gap between the local population, many of whom still view the

leopard as a livestock killer, and the Omani government, which seeks to protect

an endangered predator. Spalton is keen to demonstrate that preserving the

leopard can bring economic benefits, partly through the introduction of

carefully controlled, low-impact tourism projects.

However,

as old conflicts are resolved, new ones are created. While the leopards need

huge territories to survive, development creeps ever closer in the form of new

roads, houses and hotels. The survey team has already noticed a decline in the

number of animals that have their pictures taken on camera-traps in one area.

What

does the future hold for the shadowy leopard of Oman's Jabal Samhan? “To keep

its place in the mountains, the leopard needs to find a place in people's

hearts and minds,” says Spalton. Having adapted its habits to survive the 2200

years since the time of Agatharchides, the leopard may be able to succeed in

making this further critical last leap.

If

it can't, then the only place the next generation will see this mysterious

mammal is on film.

To find out more about the Oman

Arabian Leopard Survey, visit www.oryxoman.com/leopard_main.html.

Click here to view the original article (pages 24-31

of the March/April 2009 Saudi Aramco World).

| Anna

McKibbin is a free-lance nature correspondent ([email protected])

who is fascinated by the wildlife of the Middle East. |

STANDARDS

This lesson correlates to the following national standards for world history and language arts, established by MCREL at http://www.mcrel.org/:

- Understands the concept of extinction and its importance in biological evolution

(e.g., when the environment changes, the adaptive characteristics of some species are insufficient to allow their survival; extinction is common; most of the species that have lived on the Earth no longer exist)

- Gathers and uses information for research purposes

- Demonstrates competency in the general skills and strategies of the writing process