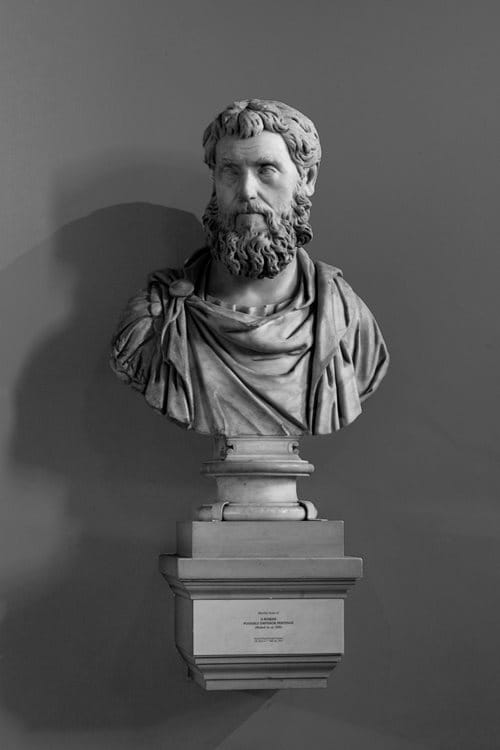

The Emperor from Africa

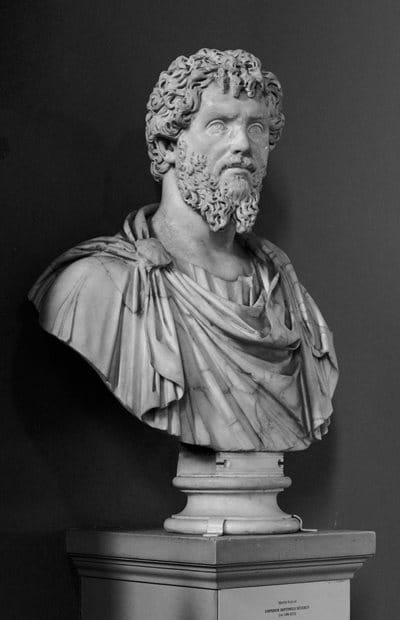

One of two sons of a wealthy, politically ambitious, olive-farming family, Septimius Severus grew up in Leptis Magna, along what is now the coast of Libya, in the second century ce. At first not the most promising of teenage scions, he matured to take high command posts on the Danube frontier and, at 48, became the Roman Empire’s first emperor born on the African continent. Over his 18-year reign, he rarely sat on a throne in Rome, preferring travel with the legions to frontiers and far reaches where his efforts expanded the empire to its greatest extent and left legacies in law and architecture that endure today.

“Toward friends not forgetful, to enemies most oppressive; he was capable of everything that he desired to accomplish, but careless of everything said about him.”

—Cassius Dio

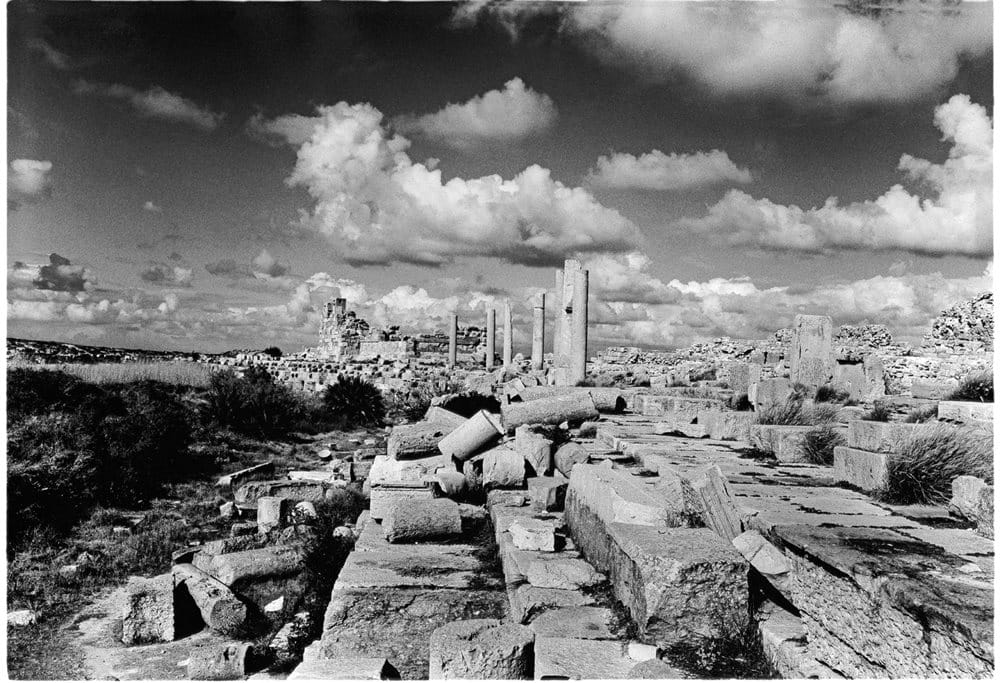

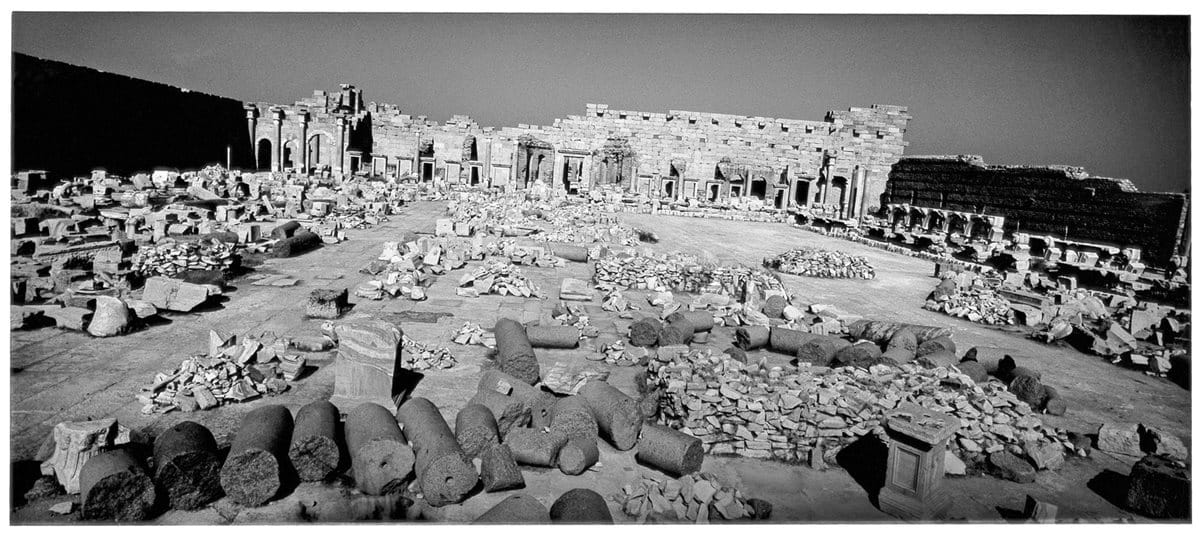

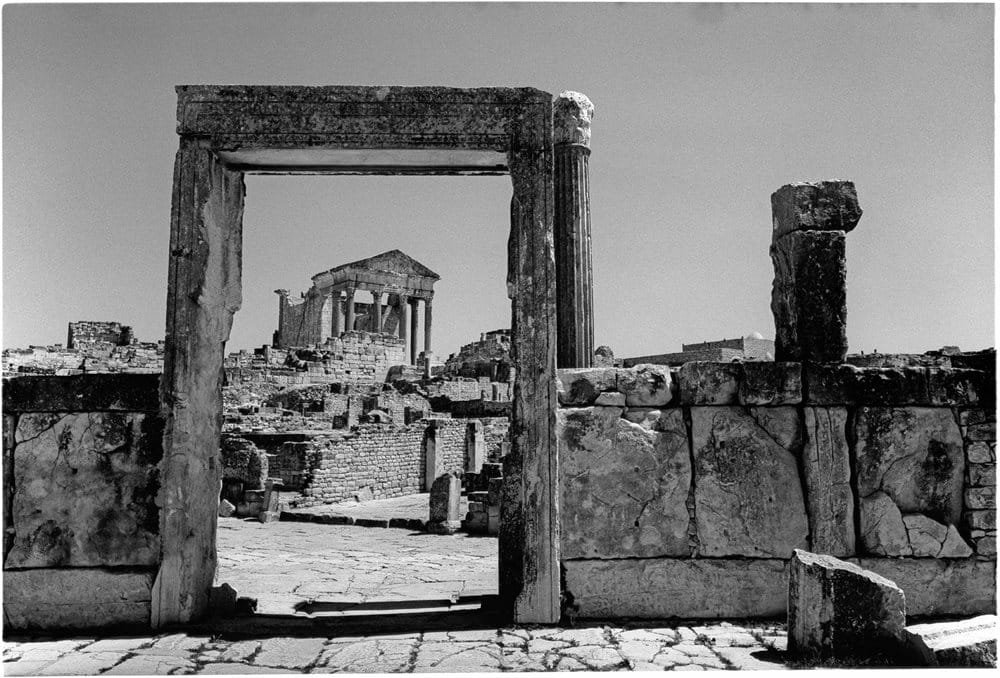

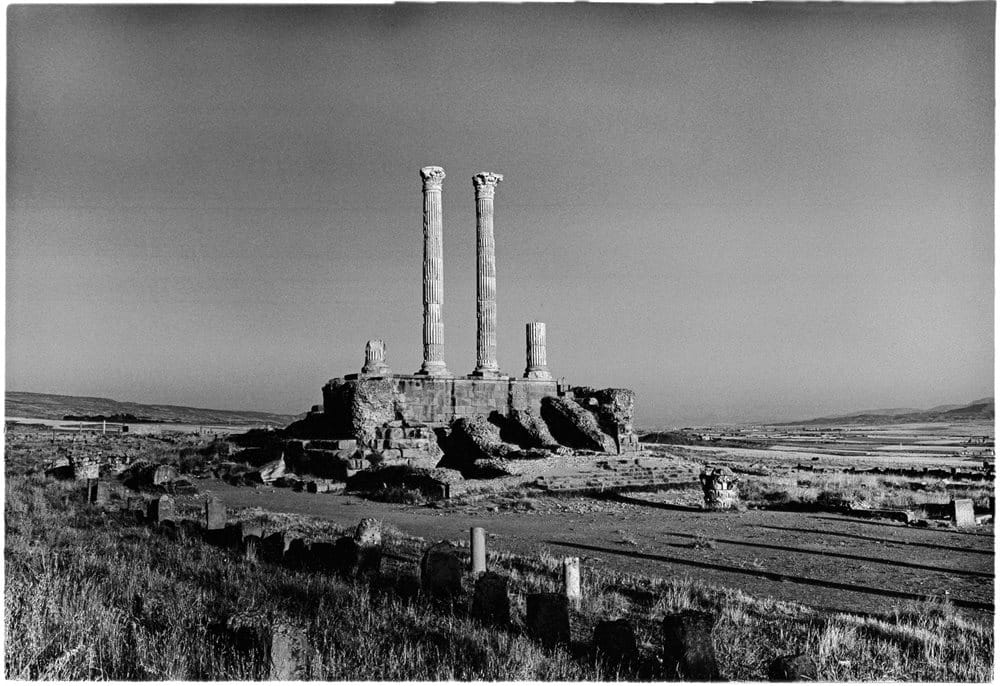

It is tranquil these days at the triumphal arch of Septimius Severus in Leptis Magna, on the coast of Libya. The cube of white marble, scooped through by four arches and decorated with friezes of Septimius and his family, stands like a museum piece on the city’s southern edge. But it’s easy to imagine dusty foot, hoof and cart traffic bustling around the edifice some 18 centuries ago when the arch straddled the coast road running west to Carthage, in what is now Tunisia, and the road south into the Sahara.

Like many of the city’s magnificent ruins, the arch speaks to the power and resourcefulness of the first African to rule the Roman Empire. Septimius, who ruled from 193 to 211 ce, was the 18th emperor in a line dating back to Julius Caesar in the first century bce.

As a Briton, I have always been fascinated that this politician, military commander and architect, whose triumphs in western Asia, Europe and North Africa took the Roman Empire to its greatest extent, should die amid an unsuccessful three-year campaign to conquer Caledonia (in present-day Scotland). Of all the paths he might have taken from his triumphal arch, which he had dedicated in 203, the one that led to the empire’s northwestern frontier seems the least likely. Or does it?

Septimius was born in Leptis Magna, a port city wealthy from its export of olive oil, in 145. His family, like those of most of the town’s leading merchants and landowners, maintained ties to trading cities of the Phoenician coast (in modern Lebanon and Syria) that even then were regarded as ancient places. Septimius grew up speaking Punic, the language of much of North Africa, and he was schooled in Latin, the language of the empire.

At first glance his ascent from the province of Africa to head of the world’s superpower appears as improbable as his final trek to Britannia. Much of what we know about him comes from the writings of Cassius Dio, who became one of the greatest Roman historians. (See sidebar below) Dio knew Septimius personally, and both also served as Roman senators. His portrayal of Septimius formed an important part of his 80-volume Roman History, which he began writing in the early third century. Notably, Dio wrote that he started the project with Septimius’s blessing after publishing “a little book about the dreams and portents which gave Severus reason to hope for the imperial power.”

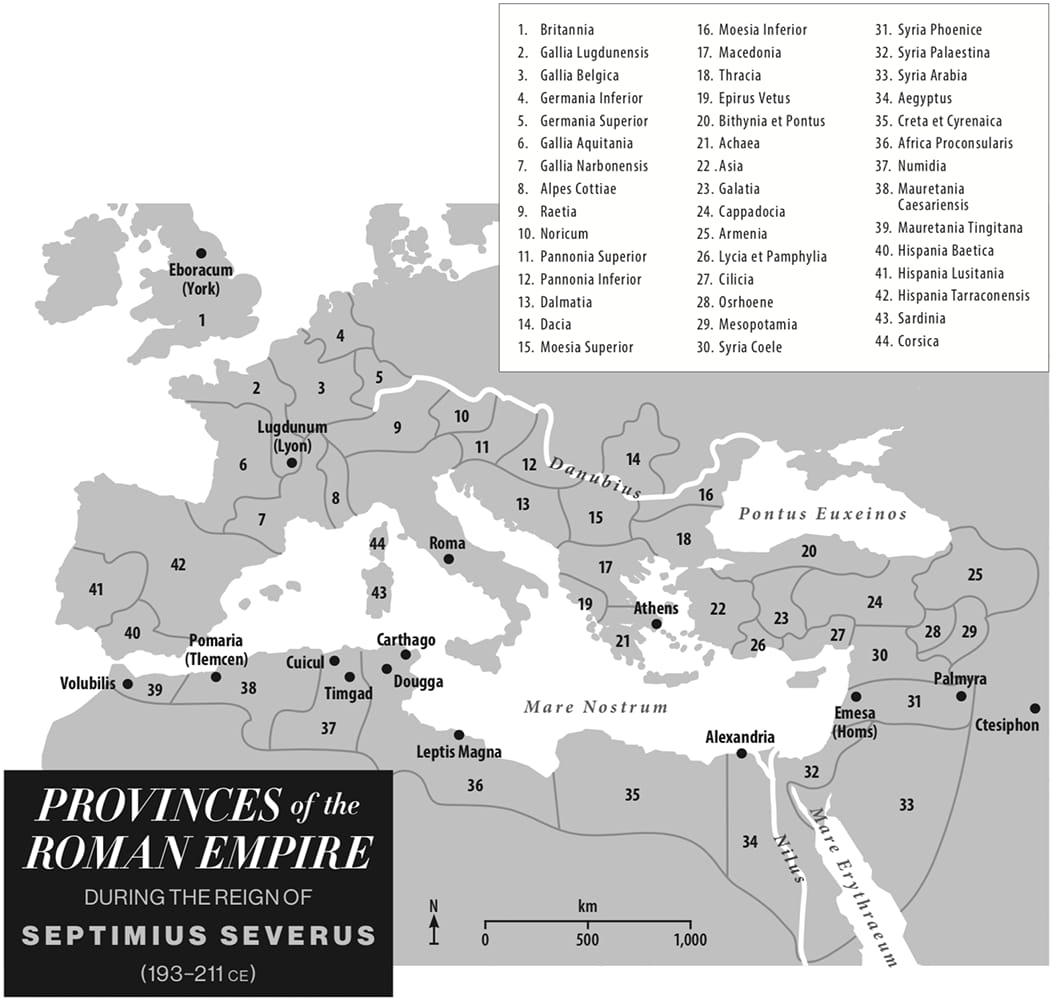

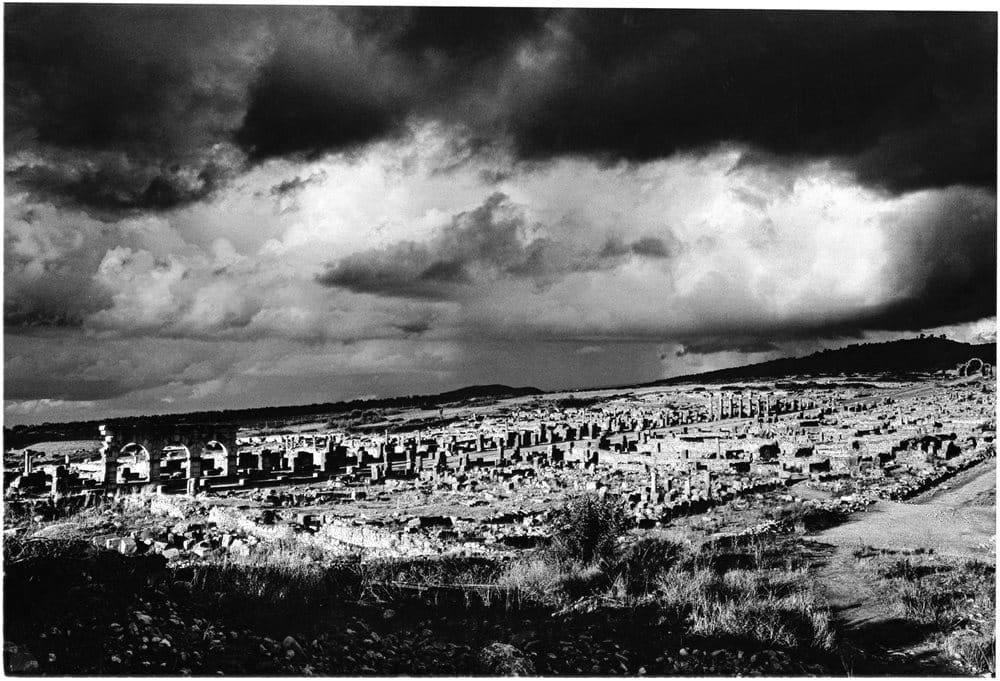

To understand Septimius’s achievements, we must strip away some modern assumptions and try to grasp his worldview. The first thing to discard is any sense of “national identity.” The determining facts about any individual during the time of Septimius were one’s city, one’s family and one’s legal status. At his birth the Roman world consisted of a constellation of 2,500 self-governing cities, and of these, one-fifth of them were in North Africa.

Cities in Septimius’s world ranged from ancient hilltop citadels such as Dougga in northern Tunisia, with a population of 2,000, to sprawling ports like Carthage near today’s Tunis, which numbered more than 100,000. Leptis Magna was in between, with a population of around 40,000. Each city, whatever its size, was dominated by a tiny minority of privileged landowners, the curiales.

To be a member of this class, a family had to own land worth at least 300 gold coins, or aurei, and produce an income of 30 aurei a year (values for the aurei are notoriously wide-ranging, from $1,000 to $10,000 in today’s currency). Landowners collectively gathered taxes and remitted them to Rome, served as priests in the local temples and as magistrates who administered the cities, and sat in the curia, the town council.

In their hometowns members of the curial class were part of a privileged elite, but from the perspective of the imperial court in Rome, they were very nearly chaff—among 65,000 provincial landowners. Only the top one percent of this body were wealthy and talented enough to aspire to become a member of the real ruling class of the empire—the 2,000-man Senate in Rome.

Septimius Severus became one of this number. His wealthy North African family, infused through marriage with Italian blood, had aspired toward this rank for four generations. The first step had been to acquire landed estates in Italy. Bankers or merchants could become senators if they turned their backs on trade and invested their fortunes in land.

The next step was to convert old North African names and provincial accents to Roman equivalents. Septimius’s grandfather and namesake, Lucius Septimius Severus, had been placed as a young man in the household of Quintilian, who held the imperial chair of rhetoric in Rome (the equivalent today of a Harvard professor who doubles as a popular television presenter). Speaking and writing proficient Latin was essential for anyone aspiring to a career in the law courts, and it was the first step on the ladder of imperial administration.

Lucius Septimius had been content with his modest public role as a barrister giving legal cases a first hearing. But he was also making social connections that would help the next generation of his family: He became friends with the historian Tacitus, the poets Martial and Juvenal, and Pliny the Younger, a literary-minded governor.

Two brothers from that generation, Publius Septimius Aper and Gaius Septimius Severus, both served appointments as consul to the top tier of administrative magistrates, starting in 153 and 160 respectively. Both were cousins to Septimius’s father, who remained in Leptis Magna, perhaps helping to oversee the family’s olive orchards and shipping business. Thus when 18-year-old Septimius Severus sailed to Rome, he did so as part of a well-established clan.

He followed in the path of his elder brother, Geta, who made a good start to a public career. Geta had secured a vital patronage connection with a brilliant young man named Pertinax, who would go on to briefly rule Rome himself even though he had no aristocratic clan behind him. Though Septimius’s first appointment was to an unpromising post in Sardinia, through Geta and Pertinax, the brothers rose to leading military roles.

There were in all the Roman Empire only 25 legions. Geta commanded two of them on the lower Danube. Septimius led three on the upper Danube, in the neighborhood of today’s Serbia and Hungary, beginning in 191. This made for an exceptional position of power for a single family, one critical to the defense of the empire from the Germanic tribes that would, in the late fifth century, finally conquer Rome. It reveals the degree of trust vested in them by Pertinax, who was then in Rome running the imperial administration on behalf of the increasingly insane Emperor Commodus.

Two years later, fortune threw down a challenge: Commodus was assassinated on the final day of 192 and was succeeded by Pertinax, who was killed three months later at the instigation of the Praetorian Guard, the elite military unit responsible for the ultimate safety of Rome, which then auctioned off the imperial throne. Septimius with his legions made a bid, his brother Geta now in his shadow, while legions in other parts of the empire acclaimed two other candidates. It was thus that 193 became known as “The Year of the Five Emperors.”

Septimius emerged triumphant in the internal wars that followed. He seized the capital and furthered his hold on legitimacy by standing as the avenger and heir of Pertinax. To crush the Praetorian Guard, he summoned its members to meet him in the open before he arrived in Rome, and “while they were ignorant of as yet of the fate that lay before them ... relieved them of their arms, took away their horses, and banished them from Rome,” wrote Dio. Septimius then doubled his legionnaires’ pay, a move that helped ensure their loyalty but also made him, and future emperors, increasingly dependent on the military.

A man from the provinces who saw his security in efficient government rather than greed and opulence, he displayed indifference for the privileges of Rome. For all but three of his 18 years as emperor, Septimius ruled from provincial cities and military camps as he led prolonged tours and campaigns through the provinces and frontier regions.

Success often traveled with him. On the eastern frontier, against the Parthian Empire, he captured their capital Ctesiphon, in present-day Iraq, and expanded Rome’s reach. In Arabia he strengthened the frontier defenses with forts to guard the trade routes that gave access to both east and west shores of the Arabian Peninsula, earning himself the title Arabicus. He journeyed to Egypt and traveled up the Nile, visiting ancient religious sites and relaxing longstanding restrictions on local religious expression. Then, as a dutiful son of Leptis Magna, he campaigned in the Sahara, extending the frontier to the outer edge of cultivable land, some 150 kilometers from the coast.

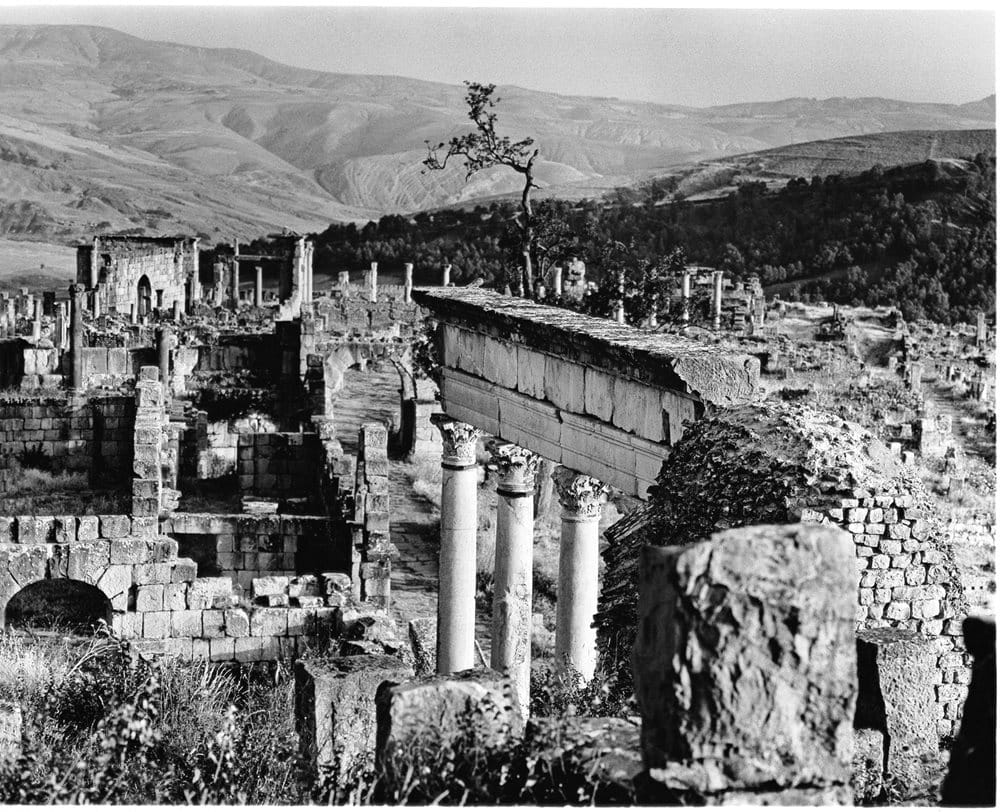

Personally pious, he disseminated a philosophy that underpinned his revival of traditional worship in temples across the Roman world. He also restored public monuments and built new ones that explored new architectural themes. He began the codification of Roman law to make it more consistent and accessible across the empire, a legacy that became part of the foundation of the sixth-century Justinian Code of the Eastern Roman Empire, principles of which are reflected in Western jurisprudence today.

Septimius seems to have undertaken these tasks with a conception of the empire as a commonwealth, with a reduced role for Rome’s privileged ruling class, perhaps due in part to his own provincial origins and perhaps also to his wide travels. Likewise, his perspective led him to advocate religious tolerance and even what we would call today cross-cultural inclusion. Nor was he a one-off: His son, Emperor Caracalla, completed many of his father’s building projects and extended Roman citizenship across the entire empire.

Septimius achieved his goals as much through logistics and engineering as anything else. Traces of his work are still visible in the shape of roads, bridges, storehouses and frontier fortresses. In addition to forts on the southern frontier, he constructed the 120-meter Severan Bridge over the Chabina River on the frontier in southeastern Anatolia, one of the longest remaining Roman arched bridges; established Pomaria, the western frontier fort that would grow into the city of Tlemcen in today’s Algeria, and he expanded forts at Coria (Corbridge) and Arbeia (South Shields) in Britain.

Today, color-coded historical maps highlight the boundaries of the empire under different rulers. The Romans also made maps but tended to visualize space in terms of itineraries, lists of place names fanning out from Rome (or any administrative base) and port cities connected with inland towns and legionary fortresses on the frontier. Formal gatehouses, often ornamented with a triumphal arch that the Romans delighted in building throughout the empire, were part of this system of imagining the world. They honored the emperor in their dedications, but also established a clear direction of travel for the next city, a measured starting point for the succession of milestones.

What is especially fascinating about Septimius is that as well as reinforcing and extending the empire’s borders, he sustained and bridged parallel cultural identities, maintaining his North African ties while laying the foundations for an imperial dynasty that lasted 24 years beyond his death until 235.

He stayed true to his hometown heritage by the choice of his first wife, Paccia Marciana, around 175. After her death he married Julia Domna, daughter of the high priest of Emessa (Homs, in modern Syria) in 186 or 187. She hailed from an Arab dynasty that had ruled the Syrian desert as allies of one of the kingdoms established by heirs of Alexander the Great. Though this would have meant nothing in the Roman Senate, it clearly resonated with Septimius, who spent years campaigning in the East.

The temples that Septimius restored and the shrines and processional avenues that he built show both piety and an understanding of the political and cultural roles of religion. In this way, he was the last emperor to preside over an intellectually confident pagan world, one where far older beliefs were honored alongside interests in new ones.

Temples housed libraries, oracles, healing priests and teachers. Above all this, there was a conscious attempt to assimilate different traditions of belief. Concepts such as the immortality of the soul and its migration, an ethical life, and judgement after death were already universally acknowledged.

This is not to paint a portrait of a saint. Septimius came to power by winning civil wars in Syria and Gaul (France). He had potential rivals killed. He purged the senate, and he gave his army license to sack conquered cities. In Caledonia, on what would become his last campaign, he gave his soldiers the pitiless instruction, quoting King Agememnon in Homer’s Iliad, to “Let no one escape utter destruction, let no one escape our hands,” observed Dio.

What precipitated this final, ultimately futile, campaign?

Very few Roman emperors had ever wished to visit Britannia, let alone dedicate their later years to the conquest of the otherwise obscure island on the edge of the known world. It’s likely that Septimius envisioned conquest as a prerequisite to later deploying his military more effectively. A single legion guarded the empire’s entire Saharan frontier, for example. He likely also wanted to bond his sons, Caracalla and Geta, with the army in preparation to assuming rule themselves.

Septimius also at the time was suffering from gout. He had to be carried in a litter much of the way to the army’s headquarters in Eboracum (York) in 208. His forces initially succeeded in occupying central Caledonia, but the highland clans struck back the next year, and the battlefield-trained Roman forces proved no match for the Caledonian guerrilla tactics.

The emperor’s last words were advice to his sons: “Give money to the soldiers, and despise everyone else,” Dio recorded. While they seem bleak, even cynical, we know that he did not always follow his own recommendations. He left a legacy of reformed laws, reinforced frontiers, restored temples and dozens of cities adorned with fountains, shrines, storehouses, processional avenues and marketplaces.

Among the loveliest is his cuboid marble triumphal arch in Leptis Magna. By the 20th century, it had fallen to ruin, but archeologists recovered its fragments and, in 1928, pieced if back together. Now, it stands to commemorate this crossroads emperor from Africa whose sense of shared civilization stretched from Iraq to the border with Scotland, and from the Sahara to the Danube.

About the Author

Barnaby Rogerson

Historian, author and publisher Barnaby Rogerson’s recent books include A History of North Africa (2012), and In Search of Ancient North Africa: A History in Six Lives (2018). He has also written guidebooks to Morocco, Tunisia, Cyprus and Istanbul. His day job is running Eland Books (www.travelbooks.co.uk), an independent publisher of classic travel books.

Don McCullin

Don McCullin is one of the most acclaimed photographers of conflicts and emergencies around the world. In 2017 he was knighted, and in 2019 the Tate Britain gallery mounted a retrospective exhibit. Recently he has pursued landscapes, still life and travel, which have come together in ongoing work on the fringes of the Roman Empire, including Southern Frontiers (2010), with Barnaby Rogerson.

You may also be interested in...

AramcoWorld: 75 Years of Cultural Connections

Arts

History

Since its origins in 1949 as a company newsletter for Aramco, AramcoWorld has evolved to focus on global cultural bridge-building across the Arab and Muslim world and beyond.

AramcoWorld Explores Universal Food and Cross-Cultural Identity

Food

History

AramcoWorld: Celebrating 75 Years of Global Historical Insight

History

Cover stories that bridge the past and present offer insights into humanity’s common ground. From archeology to historical objects, people, places and more we share connections to one another.