AramcoWorld: 75 Years of Cross-Cultural Connections

In 2024 AramcoWorld is marking 75 years of transcending cultural barriers. From its early days as an intra-company newsletter seeking to enrich understanding between employees in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and the original Aramco headquarters in New York, it evolved into a full-blown magazine focused on engaging external audiences around the globe. This first in a series of anniversary articles follows the timeline of a publication whose bridge-building mission continues.

AramcoWorld Marks 75 Years of Transcending Cultural Barriers

For three-quarters of a century, the magazine has trained its broadening lens on the world.

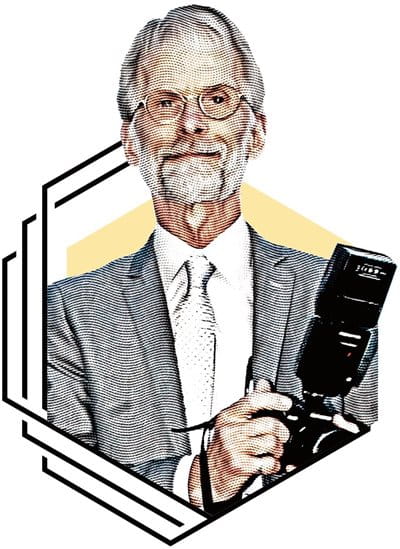

“The beauty of the magazine is the broadness of its scope; there are so many subjects out there that represent the Arab and the Muslim worlds in interesting and exciting ways, and each of those areas is a wonder to explore.”

—Arthur P. Clark

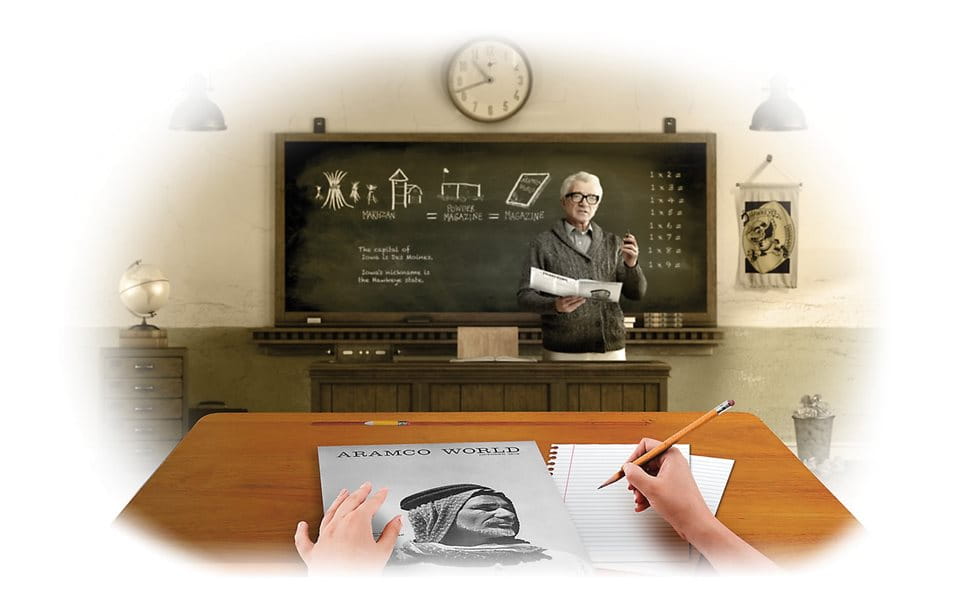

In Arthur Clark’s first interaction with AramcoWorld in 1958, he immediately noticed its difference from the staid informational pamphlets he and his classmates received.

During a lesson on business-letter writing in elementary school, he'd penned a simple missive to its publisher, Aramco, hoping for a bit of intellectual stimulation.

“I was a third grader growing up in a little town in Iowa, and it was an opportunity to learn about people and places that I didn’t know about and receive colorful publications, which were interesting to the eye.”

Along with the magazine, Aramco sent a note saying that educators could receive free copies of each issue. Clark's mother was a teacher in a nearby town and he enrolled her so that they both could read AramcoWorld. That began what would become a decades-long love affair fueled by unquenchable curiosity, during which the magazine delivered, bringing exotic locales to life through vibrant pictorials and fascinating stories.

Nearly 10 years into its journey at that point, AramcoWorld had already blossomed from a practical intra-company newsletter into a full-blown magazine focused on external audiences. What started as an exercise in cross-cultural understanding between employees in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and the original headquarters of Aramco in New York had extended its mission to the world, building bridges through the sharing of knowledge.

As it celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, the magazine remains intent on continuing this legacy of drawing in writers, editors, artists and photographers passionate about the power of sincere storytelling to challenge stereotypes, open minds and alter perceptions.

This is the first in a series of articles celebrating this history—how in 1949, a company’s willingness to honor partners in the newly tapped oil fields of Saudi Arabia spurred a continuous effort to broaden the lens on a region (and religious heritage) often neglected or misrepresented in modern media.

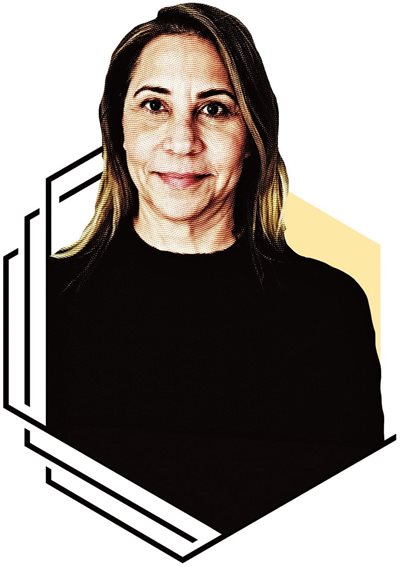

“Being Arab American—it was very therapeutic to be able to tell our story, especially because of the way we left [Lebanon].”

—Alma Kombargi

For a young Clark, the magazine was an awakening.

“AramcoWorld was especially fun because it had more than just pictures and stories about products—it had stories about culture and economy and history, all kinds of things that were exciting and new.”

Alma Kombargi, who has held various roles in public affairs at Aramco Services Company for 17 years, had a front-row seat to the development of the magazine after its headquarters made a gradual odyssey. It hopped to various Aramco offices, first in Dhahran and then to Beirut, Lebanon, in the mid-1960s, to the Hague in 1975 and finally to Houston in the 1980s, where Alma landed and where the magazine remains headquartered today.

Her father, longtime Aramco public affairs executive Shafiq Kombargi, played a key role in ensuring that the magazine didn’t veer solely into self-promotion, working with strong editors like Rob Arndt to champion its cultural mission to balance out what he saw as unbalanced coverage of the Arab world.

A pet peeve of Shafiq’s was what he called the “TV Arab,” a caricature he saw as all too common in media and books, especially as relations with the West frayed during the oil embargo of the 1970s.

“He was trying to counter all that by showing the whole world the history, depth of language and the arts of the region,” says Alma. “He was very much an Arabist Palestinian and knew a lot about the whole region—there was so little information or magazines about the Arab world. That was a big tool that he used for public affairs.”

Shafiq Kombargi provided connections, guidance and administrative support to AramcoWorld for more than 35 years along with helping define the message of cultural bridging.

Alma is among the four out of five siblings who followed their father into working for the company, perhaps out of deep-seated loyalty, she said: Aramco flew the family to the United States after their father received a death threat during the Lebanese Civil War.

Helping oversee the magazine honors his legacy and makes sense of her immigrant experience, she says.

“Being Arab American—it was very therapeutic to be able to tell our story, especially because of the way we left,” Alma says.

That someone like Clark, meanwhile, would go on to become an assistant editor for the magazine is perhaps not surprising. As the son of a local news editor and graduate of the Georgetown School of Foreign Service, he most likely would have found a career with an international outreach.

His passion for the Middle East and the Islamic world was not a given; rather he says the publication helped foster it.

After college, Clark joined the US Peace Corps in Morocco, then went to Egypt for a newspaper job and began writing columns for his hometown paper interpreting life in that part of the world for readers who grew up just like him.

Over the years, Clark says, he both adopted and shaped the unwritten formula of an AramcoWorld story as he tackled topics like how Middle Eastern archaeology influenced Agatha Christie or how a Saudi astronaut was changing the face of space exploration.

These stories, as he learned from longtime editors like Rob Arndt and writers like Paul Lunde, had to “breathe,” pulsing with life and energy and imbued with empathy.

“The beauty of the magazine is the broadness of its scope; there are so many subjects out there that represent the Arab and the Muslim worlds in interesting and exciting ways, and each of those areas is a wonder to explore,” Clark says.

“I love that you can pick the magazine up and disappear into other worlds and step back into your world and it has changed.”

—Piney Kesting

Piney Kesting has experienced this for more than 30 years, during which she estimates she has averaged a little more than one freelance piece a year for AramcoWorld, starting with a 1989 feature on Saudi Arabia: Yesterday and Today, an exhibition about economy and society she followed as it toured cities across the US.

“I saw how interested people were in all the cultural aspect of Saudi Arabia, which to them was linked to oil in their minds,” she says, remembering how the inclusion of female artists opened the eyes of Americans. “It sort of plucked away at the misperceptions they had about Saudi culture.”

Like Clark, she sees the magazine as a teaching tool and enjoys highlighting human achievement and inspiring readers to be a little more engaged and culturally empathetic by foregrounding their commonalities instead of differences.

A few examples of many, she says, are her profile of California-born calligrapher Mohamed Zakariya and a look at a transformative literacy program started by molecular biologist Rana Dajani in Amman, Jordan.

“I love that you can pick the magazine up and disappear into other worlds and step back into your world and it has changed,” she says.

She has also traveled extensively for the magazine, first for a story on the last surviving Cold War sister-city relationship between Seattle and Tashkent, Uzbekistan. The piece transformed her thinking on Central Asia and showed demand for a broader international lens (she later returned to examine art in Tashkent’s metro stations).

AramcoWorld’s “eager audience,” she says, generates more feedback than anything else she has produced.

“I get emails from Africa, Europe and the Middle East from people who will write long thank-yous—‘Wow, I never knew about this, and I’m so interested.’”

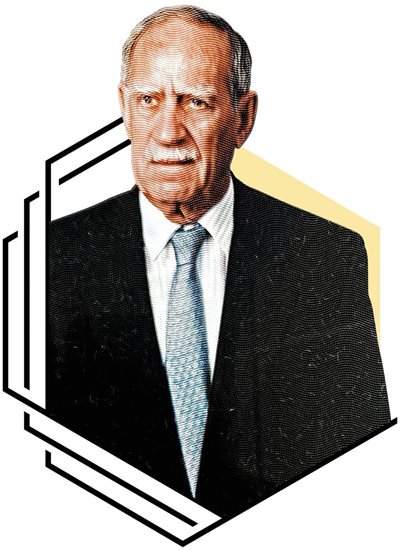

“AramcoWorld helps its readers widen their circle of inclusion.”

—Richard Doughty

For the magazine’s global shift, Kesting credits Richard Doughty, who joined via a similar path to Clark, intersecting with the latter at Aramco for many years. A photojournalist who supported himself in graduate school by teaching and writing, Doughty positioned himself as a dual threat who could win jobs by keeping publications from having to shell out travel expenses for two people.

In 1989 Doughty landed a photography internship at Cairo Today magazine, but before he left for his first Middle Eastern adventure, fellow photographer and “Aramco brat” Wendy Levine told him he should check out the magazine. He grabbed his first gig, photographing and writing a story on a French road rally that traversed Egypt.

As he continued to travel to the Middle East and prepare a thesis on how magazines covered conflict in Palestine, Doughty noticed a tendency, both within himself and other photographers and publishers, to “exoticize” or “other-ize” Arabs.

“They’ll wait until the modern-dressed person was out of the frame, and then they’ll take a pic of the old man in the robe smoking shisha because it looks like ‘old Egypt,’” he says.

Locals, he says, knew instinctively what journalists were doing, and they resented the way narratives were being shaped. The realization spurred a book project in Gaza where Doughty and his collaborators recorded and relayed subjects’ own descriptions of his photographs.

AramcoWorld, he would find out, shared an interest in providing context at this level.

“I saw AramcoWorld as the place where the Arab world and Muslim cultures were a priori part of an us and not a them, and I liked that very, very much,” he says.

Doughty joined the team as assistant editor in 1994, and went on to become editor in 2014, continuing to inculcate inclusion as the publication’s geographic scope, subject matter and readership began reaching even further into the Islamic world beyond the Middle East, from Bangladesh to Indonesia, as well as highlighting stories of migrants bringing their Arab or Islamic culture to third countries.

“We pick a photograph and walk through students analyzing the photograph. Why is it framed the way it is? What effect does it have on you as a viewer?”

—Julie Weiss

In the years since the publication marked its golden jubilee in 1998, world events have conspired to bring even more urgency to the task of understanding the Middle East and the Islamic world, yet a deficit remains.

Julie Weiss, a longtime consultant for AramcoWorld’s outreach to classrooms, noticed misconceptions about the Middle East and North Africa and a dire need to interpret the region for a larger audience.

“People were just hungry for information—they knew the bare-bones outline of stuff that you might get from the newspapers, but they didn’t know anything else,” says Weiss, who has switched careers but still works on what’s now called the Learning Center 20 years after she was contracted by Doughty.

The Learning Center transforms the magazine’s reportage into classroom lessons. With an apolitical bent, AramcoWorld articles provided updated yet timeless stories, presenting themes of migration, trade, history and economics that could be adapted to convey specific skills, Weiss said. It also had aesthetic allure.

“What took me was the photography, the visuals,” she says.

Evidence of Doughty’s fingerprints on the project, each lesson in the Learning Center still beckons readers to practice seeing things differently, peering into a photo to understand the decisions behind its composition.

“We pick a photograph and walk through students analyzing the photograph,” Weiss explains. “Why is it framed the way it is? What effect does it have on you as a viewer?”

It all stems from a sense of cultural accountability, both subjects and readers, Doughty says.

“AramcoWorld helps its readers widen their circle of inclusion,” says Doughty, who retired from the helm in 2023. “To me, the widening of our circles of inclusion is a profound spiritual task that is at the core of what it means to be a social human being.”

“You have a higher quality of writing, and in many cases, the pieces cut through different disciplines.”

—Sultan Sooud al-Qassemi

Doughty says it’s clear that support from the company, first from the American-founded Aramco and later from its successor, Saudi Aramco, has given space for a deeper examination of cultural topics.

That’s part of the allure for Sultan Sooud Al-Qassemi, a writer, art collector and commentator based in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates.

“You have a higher quality of writing, and in many cases, the pieces cut through different disciplines,” says Al-Qassemi, whose dream came true in 2018 when he was profiled as “The Modernist” in the magazine after 25 years as a reader. “You might read an article about art that also mentions architecture, tourism and archaeology—cross-disciplinary pieces that you don’t see in other publications.”

In a part of the world where neglect has led to the closure of daily newspapers and art is often a casualty of war, AramcoWorld’s seven-decade archive is an invaluable resource for researchers and groups like Al-Qassemi’s Barjeel Art Foundation, which protects, restores, exhibits and promotes works from throughout the Middle East.

Al-Qassemi has personal proof from working on his book Building Sharjah. Uncovering a brief reference to Gordon Ivory, a British architect active in Lebanon and around the Gulf in the 1960s, kept him from “a wild goose chase” and helped him attribute three to four new buildings to which he could find no other extant reference. That the article was still relevant was fitting for the publication, he says.

“If you pick up a copy of AramcoWorld, you can easily come across an article about Ottoman Cairo, Syria, civilizations from a few hundred years ago or read about contemporary art. What I like about AramcoWorld is that there aren’t timelines. You can read it in a year or two or three, and it is like a time capsule.”

“What I like about AramcoWorld is that there aren’t timelines. You can read it in a year or two or three, and it is like a time capsule.”

—Barnaby Rogerson

Barnaby Rogerson, who runs the small travel imprint Eland Publishing in London, says it’s refreshing that AramcoWorld can show such “fearless enthusiasm” for the Arab and Muslim worlds while examining impactful legacies of Western travelers and the educational institutions founded by foreign powers.

AramcoWorld, he says, is “up with the angels” when it comes to centering local voices globally.

Rogerson first encountered the magazine many years ago at a since demolished British consulate in Tunisia.

“The consulate had a library on the ground floor much used by students, and there, much to my delight, I came across an article on the great historian Ibn Khaldoun,” Rogerson says.

Since then, he has been a reader and frequent contributor, to the point where he wanted to meet up with an AramcoWorld team member in London.

With the magazine headquartered in Houston, he expected to rendezvous with a loud and proud Texan. Instead, Clark showed up.

“It was a surprise that when I met my first AramcoWorld staff member for a coffee at a street café near the British Museum, that Arthur was a thin, book-loving, scholarlike sage,” Rogerson recalls.

Ever since the third grade, AramcoWorld has fed Clark’s curiosity in the easy, entertaining way that he would dare say nourishes all its readers. “It’s educating people without telling them that you are educating them.”

About the Author

J. Trevor Williams

J. Trevor Williams is a global business journalist based in Atlanta where he serves as publisher of the online international news site, Global Atlanta (globalatlanta.com). Follow him on Twitter @jtrevorwilliams.

Ryan Huddle

Ryan Huddle is a Boston-based graphic designer and artist whose work appears regularly in the Boston Globe and other leading publications.

You may also be interested in...

Grand Egyptian Museum: Take a Tour of the New Home for Egyptian Artifacts

Arts

The Grand Egyptian Museum has officially opened its doors, revealing treasures from the ancient Egyptians and their storied past.

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.

Art Biennial Reviving the Ancient City of Bukhara, Uzbekistan

History

Culture

Uzbekistan’s inaugural biennial reactivates an ancient stop on the Silk Road through artworks jointly created by international and Uzbek artists.