Green Mosques Generate Positive Energy

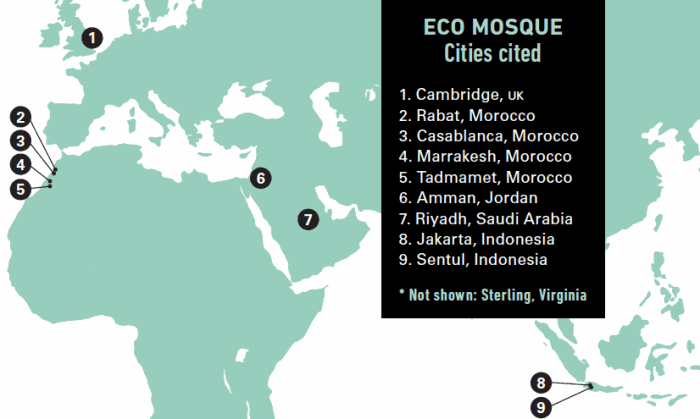

From Jordan and Morocco to Indonesia, the uk and more, communities and governments are supporting eco mosques. The goals: education and thrift. “We want to lead by example,” says the manager of Masjid Az-Zikra in Indonesia.

Up on the roof of Masjid Abu Ghuweileh, Yousef al-Shayeb looks around and smiles, gesturing to an array of solar panels tilted south toward the sun. The masjid, or mosque, is located in Tlaa al-Ali, a thriving district in northwestern Amman, Jordan, where he heads the building’s management committee.

“This was stage one—44 panels. Over there was stage two—64 panels. Now we are all set—for the next 20 years at least,” al-Shayeb says, mentioning the pride he feels for leading the project to install the solar panels. “I served the military, and now I serve the community, this house of God and everyone in this neighborhood.”

An electrical engineer by trade, al-Shayeb spent 22 years with the Royal Jordanian Air Force before retiring in 1990 as a brigadier general. Then he transferred his professional and technical expertise to his community in Tlaa al-Ali.

Masjid Abu Ghuweileh is not a large building. A recent extension allows up to 650 worshipers for the Friday midday congregational prayer, though average attendance is fewer. The mosque is a mainstay of the neighborhood, says al-Shayeb, who moved to the area in 1986; even then it was a cornerstone of community life.

Until a few years ago, the mosque’s monthly electricity bill ran upward of 1,000 Jordanian dinars (about us $1,400). Today, thanks to solar panels on the roof, the bill is zero, al-Shayeb says.

The upgrade forms part of a Jordanian government initiative to retrofit mosques across the country with solar photovoltaic (pv) panels. These convert sunlight—abundant hereabouts—into electricity. The initiative is administered through the Jordan Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Fund (jreeef), established in 2012 as an office of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources.

The project at Masjid Abu Ghuweileh is among a number of “green mosque” schemes in Jordan and elsewhere around the world intended to help meet conservation and climate challenges at a grassroots level.

“Electricity and energy consumption is a very big issue in Jordan,” says Lina al-Mobaideen, an engineer who heads project development at jreeef. “The heaviest worries are about how we can reduce demand, and so reduce the overall energy bill. This led the government to [formulate policy] encouraging individuals to reduce their consumption.”

Al-Mobaideen highlights a partnership established in 2016 between jreeef and Jordan’s Ministry of Awqaf (religious endowments) to focus on places of worship as nodes of influence within every community.

“Energy consumption at mosques is very high,” she says. Islam’s five daily prayer times—at dawn, midday, afternoon, sunset and evening—mean that worshipers tend to flow in and out of mosques all day long. Lighting, as well as equipment for cooling in summer and heating in winter, often stays on throughout.

“The mosque is the most appropriate place to encourage people to change their behavior and introduce them to renewable energy.”

—Lina al-Mobaideen

“The mosque is the most appropriate place to encourage people to change their behaviour and introduce them to renewable energy,” al-Mobaideen adds.

In 2017 jreeef began launching tenders, area by area, to install solar pv systems in many mosques throughout the nation. By 2019 about 500 mosques were running on solar power, with the intention of extending the project to most of Jordan’s 6,500 mosques (the smallest have energy usage so low that conversion is often uneconomic) as well as Jordan’s smaller number of churches. Parallel schemes have been launched in educational institutions.

“It’s an awareness tool,” says Samer Zaway-deh, an independent consultant on renewable energy in Jordan and long-time educator for the Association of Energy Engineers, a us-based nonprofit organization that coordinates training for the sector worldwide. “Mosques and schools are places where people visit a lot. If people see solar pv, ask what it is, and learn more, then maybe they will choose it for their home or office.”

The project works through direct grants from the Jordanian government. Each mosque submits a proposal for a solar pv system, with size and capacity based on the building’s electricity consumption over the previous 12 months. Contractors, who are all Jordanian, then source components on the open market. One-quarter of the cost is covered by jreeef and one-quarter by the Ministry of Awqaf, which disburses the grant. The remainder must be paid by the mosque community, usually by donations from members.

“People are continuously donating,” says al-Shayeb. “The community already paid 300,000 dinars to renovate and extend this building. Then we gave priority to solar panels, because we were paying such high bills every month. People started donating right away.”

The Abu Ghuweileh mosque was one of the first in Jordan to install solar panels, as early as 2013. By 2018 the two-stage installation was complete. Total outlay came to around 35,000 dinars, of which the government paid about 7,000—a lower-than-usual amount because the mosque began its conversion independently.

Al-Shayeb calculates that with shifts in the energy market and other economic considerations the community will recoup its investment in about a year and a half, while Zawaydeh estimates a payback period of between two and three years for solar pv systems of this type. But that’s still a remarkably attractive proposition and it shows that prices have fallen substantially, even in the last few years. A 2014 study in Kuwait to convert all of that country’s 1,400 mosques to solar power suggested a payback period as long as 13 years.

“Solar makes a big difference,” Zawaydeh says. “It’s a fantastic opportunity [and the benefits] can be realized fairly quickly. It makes financial sense.”

The switch to solar power for mosques in Jordan is running alongside programs to reduce water use—the Islamic requirement for ablution before each of the five daily prayers can create heavy demand—and replace incandescent lighting with led bulbs, which use much less energy and last much longer.

Such concerns are rooted in budgetary prudence but can be corroborated in religion—a vital connection the government is making to encourage mosque communities.

“One of the things Islam teaches is not to overspend or exceed our consumption,” says al-Mobaideen. She points to verses in the Qur’an, including Sura vii:31, which is interpreted in English as, “But waste not by excess, for God loveth not the wasters,” and Sura xxv:67, which names the righteous as “Those who, when they spend, are not extravagant … but hold a just (balance) between those (extremes).”

“Conservation in spending and consumption—that’s what we use to bring awareness to people,” she adds. “It is both a financial and a religious imperative.”

This reflects the difficulty governments around the world have often faced in delivering either clear messaging or effective policy on the obvious long-term benefits of conserving energy and expanding use of renewable resources. Jordan’s approach demonstrates a holistic way forward, with environmental concern and religious direction anchored in, but secondary to, the main point: economic benefit.

Al-Mobaideen emphasizes that energy conservation is spurring debate at the supranational level within the League of Arab States, where committees exchange best-practice knowledge among countries. She identifies Morocco as the Arab world’s leader in renewable energy.

“Morocco already has the legislative framework, the institutional framework and action plans. [It has] implemented many large projects,” al-Mobaideen says.

In 2016 Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs launched a project to install solar pv, led lighting and solar water heaters in the country’s 15,000 government-funded mosques, with technical support from the German international Gesellschaft fur Züsammenarbeit (giz). Government grants cover up to 70 percent of initial costs, and as part of the scheme, imams and other clerics are being trained in issues around renewable energy and sustainable technology in order to pass the message to their congregations and communities.

“What we want to do is inform people,” Said Mouline, director of Morocco’s National Agency for the Development of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency, told cnn in 2016. “Energy efficiency is not only a matter of technology, it’s also a matter of behavior.”

In 2016 Marrakesh’s 12th-century Jami’a al-Kutubiyah became one of the first in Morocco to be fitted with pv, owing to its status as a symbol of the city. Its solar panels are hidden out of sight on the roof, while a digital display set up on the street outside reminds passers-by how much energy has been generated and the associated reduction in carbon emissions.

In the capital, Rabat, the large Masjid Assounna has cut its energy bill by more than 80 percent, saving around 70,000 Moroccan dirhams (about us $7,000) a year. The scheme has now reached Masjid Hassan ii in Casablanca, the largest mosque on the African continent, with capacity of more than 100,000 worshipers. Renovations there, under way throughout 2020, will introduce pv among a range of other measures, reducing the building’s energy consumption by more than half as part of a national transformation. That program aims to improve energy efficiencies across the Moroccan economy and create 150,000 jobs over the next decade.

Similar projects are sprouting across the Islamic world. Analysis in 2019 of a pv test system installed at a large mosque in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, calculated an annual energy bill reduction of more than half. The authors of the study, led by Amro M. Elshurafa of the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center, wrote: “If some prior planning were incorporated in the early stages of the mosque’s construction, pv can bring down the electricity bill to zero.” Other studies are commencing on pv for mosques in Libya and Malaysia. Tunisia and Egypt are both investing heavily in solar power.

“It’s about translating the language of environmental activism into more practical aspects of people’s lives.”

—Hayu Prabowo

Indonesia, the country with the world’s largest Muslim population, is also on board. In 2011 the Majelis Ulama Indonesia (mui), or the Indonesian Council of Scholars, the country’s top Muslim clerical body, launched the ecoMasjid initiative. This places Indonesia’s 800,000 mosques at the center of a national public-education effort spotlighting the environment.

“It started with the understanding that environmental degradation is not technical or technological, but a moral issue,” says Hayu Prabowo, who heads mui’s environment unit in the Indonesian capital, Jakarta. “The government approached us to complement their approach to the public. We are closer to the people because of how people congregate daily at mosques—and Islam is very rich in teaching on environmental issues.”

Hayu, who devised and oversees the ecoMasjid program, lists the criteria by which mui assesses each mosque, from the appropriateness of the site and energy efficiency, to recycling, education and effective management. He sees mosques as nothing less than a vector for empowerment.

“Empowerment is not only about economics,” he says. “It’s about safeguarding people’s health and livelihood. It’s a very complex issue. We cannot manage it alone, but neither can government. It’s about translating the language of environmental activism into more practical aspects of people’s lives.”

Of Indonesia’s 50 or so participating mosques, the flagship is Masjid Az-Zikra. Built in 2010 in Sentul, around 45 kilometers outside Jakarta, Az-Zikra became ecoMasjid’s national pilot project in 2014.

Driving south from Jakarta into the province of West Java, the highway climbs toward Bogor in the shadow of the Mount Salak volcano, nicknamed “Rain City” for its damp climate and high humidity. Amid foliage of cassava, bamboo and banana, the white domes and minarets of Az-Zikra rise above an organized grid of suburban streets under tropical thunderclouds.

The mosque stands as the centerpiece of a planned neighborhood that is home to around 150 Muslim families, founded by the late cleric Muhammad Arifin Ilham. He was formerly the mosque’s figurehead and noted across Indonesia for his tv sermons until his passing last year at age 49.

“We want to lead by example, not by talk,” says Khotib Kholil, who heads Az-Zikra’s management. “Besides coming here to learn about religion, we would like people to come to learn about the environment.”

Khotib emphasises Az-Zikra’s close working relationships with universities, technical institutes and agricultural colleges in and around Jakarta, which provide expertise on energy conservation and sustainability. One national priority is improving sanitation and water management.

Khotib identifies 10 large tanks at Az-Zikra, which hold around 50,000 liters of rainwater channeled from the mosque’s roofs. All the building’s water, sourced from wells and the rainwater tanks, is recycled three times—diverted on the fourth cycle to the surrounding gardens—and he explains how a simple adjustment to faucets has reduced the mosque’s water usage for ablutions before prayer from 14 liters per person to four.

A biogas tank buried under the courtyard generates cooking fuel from human waste, but the mosque is still spending more than 30 million Indonesian rupiah ($2,000) a month on electricity and gas. The next step, says Khotib, is pv.

On Fridays Az-Zikra hosts around a thousand worshipers at midday prayers, though for special events that number may increase 10 times or more.

“This is seen as the most complete eco mosque,” says Az-Zikra’s secretary, Arief Wahya Hartono. “It’s something we are very proud of, even if most people still don’t understand what it means.”

Back in Jakarta, Greenpeace campaigner Atha Rasyadi faces challenges from plastics in the oceans to chronically congested roads. But getting across the message of environmental conservation is, he says, perhaps the biggest of all.

“We want mosques to be talking about environmental issues. They have strong influence over their people and we want to make use of that,” he says, describing how Greenpeace Indonesia is building strategic alliances with Muslim civil-society organizations.

Hening Parlan, environment coordinator for Aisyiyah, Indonesia’s largest women’s ngo, speaks even more plainly.

“There are more than 250 million people in Indonesia, and over 80 percent of them are Muslim,” she says. “If we are not educating Muslims about the environment, we are achieving nothing. ecoMasjid is the key to making [knowledge of] climate change mainstream.”

The efforts to move toward an eco-friendly congregational environment are starting to bear fruit. Arifin helped give Az-Zikra a nationwide profile. Addressing issues around wildlife conservation, forest preservation and energy efficiency, mui is partnering with Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry on training courses for mosque leaders across the country, beginning in Aceh and Riau on Sumatra island, West Kalimantan on Borneo island and Lombok. And at Jakarta’s Istiqlal Mosque, the largest mosque in Southeast Asia, which can hold as many as 200,000 worshipers, new pv is expected to halve the current 200 million rupiah (about us $13,000) monthly electricity bill. In another green initiative, a water-treatment plant channels wastewater to a new, highly visible fountain and public park around the mosque flanking the Ciliwung River.

The next step is to move beyond retrofitting wastewater recycling or solar pv in existing mosques to including such technologies at the start of building projects.

“This is seen as the most complete eco mosque,” says Az-Zikra’s secretary, Arief Wahya Hartono. “It’s something we are very proud of, even if most people still don’t understand what it means.”

That’s an idea that has come to life in Tadmamet, a small village in the High Atlas Mountains in southern Morocco where the only public building is the newly built mosque. Its construction has been carried out almost entirely by the villagers themselves, with support from a government initiative to include solar and other green upgrades in the architectural plans. In addition to cavity walls that optimize insulation and small windows that keep interiors cool, the mosque has a preinstalled pv system, led lights and a solar water heater. It now doubles as a schoolroom for the village children, and it even feeds surplus energy back into the local electrical grid to power new streetlights.

Tadmamet is now a leading small-scale example, says Rachid Naanani of Cluster emc, a Moroccan nonprofit promoting energy efficiency in construction materials. “Beyond energy efficiency, [Tadmamet] aims to show that we can offer a mosque model which is self-sufficient in terms of energy supply,” Naanani says.

One of the larger such examples opened last year in Cambridge, England, where the Central Mosque marks the first purpose-built eco mosque in Europe. Constructed mostly from sustainably sourced Scandinavian spruce, it is one of the only buildings in the world to use cross-laminated timber on a scale more commonly achieved using steel. Its forest of 16 arcing, tree-like columns create an interlaced vault over the main prayer hall—designed for 1,000 worshipers—that is reminiscent of Gothic fan-vaulting designs used in English medieval church architecture. During the day, skylights above each column suffuse the space with natural light; after dark, energy-efficient leds take over.

Those columns support a roof that is sowed with sedum, a flowering perennial, which introduces biodiversity and improves insulation. Even under moody English skies, the mosque’s rooftop pv array generates enough electricity to cover around a third of the building’s energy needs. Storage tanks harvest rainwater and gray water from ablutions for reuse in bathrooms and gardens. Bird boxes encourage local swifts to nest.

“We wanted to add beehives too,” muses Tim Winter, the mosque’s chair of trustees. “The East London Mosque produces its own honey from hives on the roof, but we didn’t have enough space up here.”

In addition, a heat pump exploits temperature differentials between outside air and the interior to keep the building comfortable, eliminating the need for more costly air conditioning. Insulation ensures that warmth from underfloor heating is conserved in winter, and in summer, rising hot air is vented passively through ceiling louvers. The parking area, tucked underground beneath the building, offers charge points for electric vehicles and racks for up to 300 bicycles.

On a balcony above the prayer hall, Winter, who is also dean of the Cambridge Muslim College and known as Abdal Hakim Murad, speaks passionately about a building that is both beautiful and significant.

“We are showing that religion is part of the solution to the big problems of the world,” he says. The mosque “is making an important spiritual and humane statement that religion is here to counter waste, to encourage us to give thanks for the blessings of creation, to enable us to think collectively rather than selfishly about the problems that face us.”

That is a statement that, more and more, is resonating globally. In Riverside, California, activist Nana Firman heads the Green Masjid program sponsored by the Islamic Society of North America (isna), which is taking the message of conservation and energy efficiency into mosques across the us and Canada. One participating mosque, the All Dulles Area Muslim Society near Washington, D.C., recently reduced its energy consumption by one-fifth as part of a community campaign that included recycling and tree-planting.

The focus is squarely on saving money and improving the life of the community in both practical and spiritual ways.

Firman has also worked on environmental initiatives at mosques in Indonesia, where she was born and grew up, in collaboration with Parlan of Aisyiyah. This year Firman and isna coordinated a Green Ramadan initiative during the holy month of fasting, which concluded in May, highlighting Islamic environmental teachings and encouraging congregations to conserve resources.

Other nations, too, are following. In 2014 and 2015, the British government funded its own Green Mosques project, supporting Muslim communities in London. In Toronto, Canada, a sustainability project dubbed “Khaleafa”—blending the Islamic principal of stewardship (khalifa) with the environmental symbol of a leaf”—spearheads an awareness called “Green Khutbah” (khutbah means sermon). Many more mosque-based ecoprojects continue to launch, from India to Tanzania, too many to list.

“The Qur’an is a book about nature,” says Winter. “It challenges us to look around to see the order of nature; that’s the basis of Muslim theology. Integration into the natural world is the essence of the Qur’anic summons to humanity.”

One striking note shared by the messages generated around energy-efficiency schemes—whether in Jordan, Morocco, Indonesia, or the global South more generally—is positivity. The focus is squarely on saving money and improving community life in both practical and spiritual ways.

That can often contrast with how similar programs are promoted elsewhere. In many Western countries, conserving resources is still often seen as a technical issue linked to forecasts of global catastrophe.

Yet perhaps the path ahead can be as simple as these “green mosque” projects: Reduce consumption and invest in energy efficiency because it will save money and improve the quality of life for everyone.

For Jordanian energy consultant Samer Zawaydeh, it’s obvious.

“I give training to 7-year-olds and 70-year-olds,” he says. “The children know about climate change. Awareness in Jordan is growing. We understand the global issues, and we are doing our share, but here, the main reason for installing solar panels is economic.

“A very small amount is to do with social awareness and global climate change. People understand what other people are doing. If your neighbor [or] your mosque installs solar panels, you will ask yourself why—and the key reason is to get rid of the energy bill. During the past 10 or 15 years, energy costs in Jordan increased threefold. So solar is a move in the right direction.”

The writer thanks Ihab Muhtaseb in Amman and Ahmad Pathoni in Jakarta for their help in preparation of this article.

You may also be interested in...

Drone Seeding Aids Mangrove Carbon Sequestration

Science & Nature

Mangroves have been drawing increasing global attention for a quiet superpower: the ability to store up to five times more carbon than tropical forests. While coastal development, uncontrolled aquaculture, sea-level rise and warming temperatures have all contributed to the 35 percent decline in mangrove forests worldwide since the 1970s, government agencies, scientists and local communities are increasingly rallying to protect and replant mangroves. One group is taking restoration to notably new heights.

Can Fig Trees Help Us Adapt to a Changing Climate?

Science & Nature

Tunisia, where figs are one of the signature crops, has been an integral part of a just-concluded Mediterranean research project, FIGGEN, to assess how the trees thrive while climate changes are causing other crops to fail. For nearly four years scientists have worked to identify specific genetic traits that enable figs’ resilience and which varieties cope best with heat and drought. When FIGGEN publishes the results, farmers concerned for their future livelihoods may choose to grow the most promising types. Additionally, the study aims to plant a seed for preserving the biodiversity of increasingly arid ecosystems.

Inside When the Sahara Was Green by Martin Williams

Arts

He was just a British kid looking for something to read one lazy summer day in 1950s Paris when images of the Sahara’s vast expanse on a magazine cover grabbed his attention. The story, about the fossils that had then just been discovered in the Sahara’s valleys, fascinated him. “I thought, I’m going to go and see those for myself one day,” Williams recalls.