New Screens in Arab Cinema

Since the 1970s, independent filmmakers have been a rare breed throughout the Arabic-speaking world. But as a rising number of film festivals and streaming platforms open, opportunities for both artistic expression and viewing experiences are growing faster than ever.

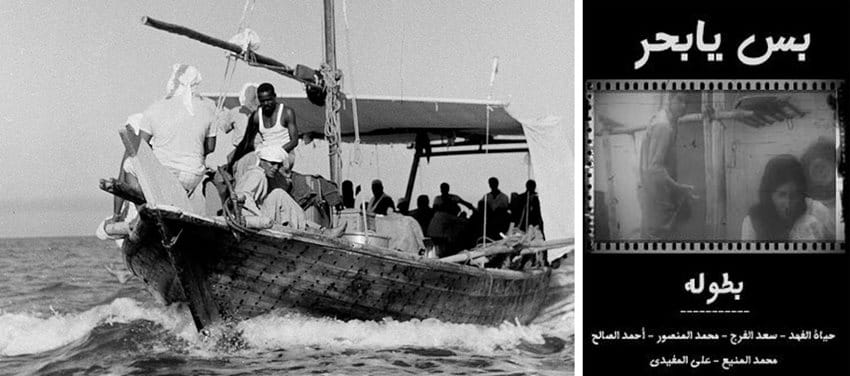

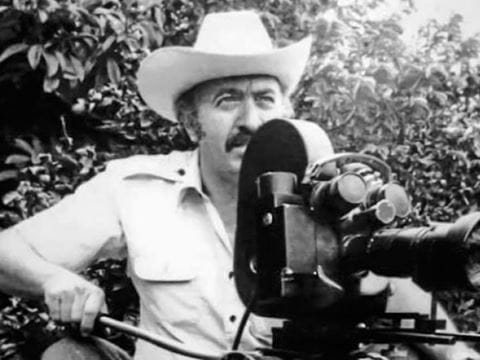

When Kuwaiti film director Khaled al-Siddiq died in October 2021, his film Bas ya bahar (The Cruel Sea), produced in 1972, was experiencing a renaissance across the Gulf region. Not only was Bas ya bahar considered the first feature film by a Gulf director, but also it is increasingly lauded as a pioneering work of socially unflinching realist cinema that broke with what was then the dominant, popular mainstream of films that were being produced in Egypt.

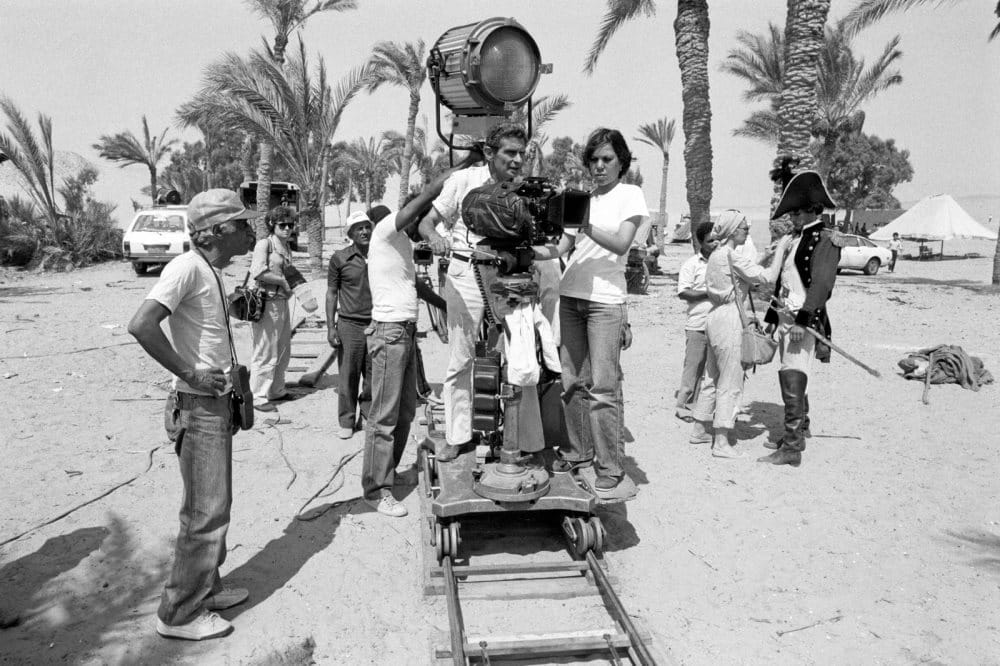

More than 50 years after the release of Bas ya bahar, film enthusiasts and historians are examining anew the 1970s era of Arab filmmaking, often referred to as the time of New Arab Cinema.

From the 1940s through the 1970s, Egyptian cinema was experiencing what is often called its golden age, which for the most part meant familiar storylines, happy endings and typecast actors. Al-Siddiq, however, looked to a darker, harsher side of life: His film told a story of Mussaid, a struggling pearl diver who dives to ever-more-dangerous depths to find a pearl valuable enough to earn him the money he needs to marry Nura, who has been promised to a wealthier man, but that pearl comes into Mussaid’s hands only on his last—and fatal—dive.

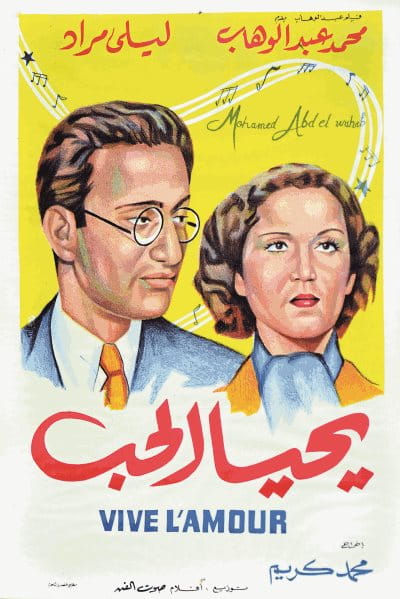

Film scholar Viola Shafik, author of three books on the history of Arab cinema, says that by the mid-1930s, Egypt had already earned international distinction as a rising film center. By the end of World War II, Egypt was producing about 50 films each year, and by the 1980s, Egypt distributed nearly 100 films per year.

Despite British colonialism, she says, “it was a relatively prosperous economy,” which allowed local entrepreneurs and artists to invest in film and create an industry that started “catering for Egypt and its neighboring countries.” The Egyptian film industry spiked in the 1980s with the introduction of the video cassette, through which it expanded its viewership into the more conservative Arabian Peninsula countries, which had few cinemas but plenty of home video players. At its peak, it was the third-largest film industry in the world, “the Arab Hollywood,” but since then, it has declined. By 2008 it was producing only about 40 films a year, and more recently it is down to 20 to 30 a year.

Film historians and enthusiasts are today also discovering anew other filmmakers of al-Siddiq’s generation whose works reflected the pan-Arab sentiments of the time, particularly al-makhduʿun (The Dupes, 1973), based on Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani’s seminal novel Men in the Sun. It was filmed in Syria, set in Iraq and Kuwait and directed by Egypt’s Tewfiq Saleh. In that pan-Arab vein, Siddiq’s only other feature film, Ors Zein (Wedding of Zein, 1976) is set somewhere in North Africa and based on a story by beloved Sudanese writer Tayeb Saleh.

Yet today, even with a rising generation producing more cinema than ever, the industry is driven less by such pan-Arab stories and more by localized themes that these days bring better opportunities for financing and distribution. Propelling this trend is the worldwide shift in viewing via online platforms and streaming services that have developed their own, content-hungry production houses.

In this sense, Bas ya bahar and others of its time are not really being rediscovered, but rather, discovered for the first time.

"The long 1970s"—the late 1960s through early 1980s—"is important for Arab cinema for a number of reasons," says Nadia Yaqub, a professor in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill whose 2018 book Palestinian Cinema in the Days of Revolution focused on the regional impacts of film in that era.

Yaqub credits the founding of several important institutions for matriculating filmmakers in the region and helping them produce substantive and highly regarded films on an international scale. The Cairo Higher Institute of Cinema, founded in 1957, was the first to offer training in film production. Public-sector film industries, which may include government-commissioned films, are prevalent in Syria and Algeria, as well as Tunisia, where the Journées Cinématographiques de Carthage, or Carthage film festival, is known as the oldest in Africa, and it has created opportunities to showcase Arab cinema and filmmakers for decades.

“Young filmmakers who came of age in the aftermath of the 1967 war were galvanized by that defeat and seized on opportunities to challenge accepted practices in a range of areas, including accepted filmmaking practices,” Yaqub says, mentioning it still took decades for most Arab filmmakers to find funding and a platform to create their projects.

The launch of the Dubai International Film Festival, which ran from 2004 to 2018, was followed by the Abu Dhabi Film Festival (2007–2015), the Doha Tribeca Film Festival (2009–2012) as well as several smaller, Gulf-based festivals that all existed to advance up-and-comers in the industry. The international festivals showcased features and shorts from global directors in many languages and encouraged creative hubs and audiences for Arab films internationally as well as locally.

In the 2000s, there weren’t that many Arab films to screen at the Gulf film festivals unless the Arab festivals helped produce them. Each festival committed to creating funding and mentorship programs, which were followed by similar initiatives from media companies and film schools throughout the Gulf region.

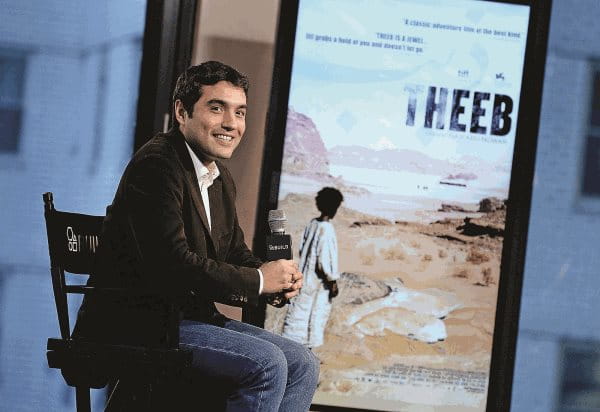

The strongest example is the Doha Film Institute and its grant program, which is still in operation and managed by Algerian producer Khalil Benkirane, even though the institute’s film festival shuttered. Since 2010 when the institute first launched, it has helped finance nearly 700 short and feature length Arabic-language films, many later recognized internationally: Annemarie Jacir’s Wajib (2017) was nominated by Palestine for Best Foreign Language Film at the 2018 Academy Awards; Moroccan filmmaker Meryem Benm’Barek-Aloïsi’s debut feature film, Sofia (2018), won Best Screenplay at the Cannes Film Festival; Sudanese filmmaker Amjad Abu Alala’s You Will Die at Twenty (2019) was nominated for Best International Feature Film at the 2021 Academy Awards; and Naji Abu Nawar’s Theeb (2014) was the first Jordanian film to be nominated for an Academy Award. The Doha Film Institute also cofinanced Oscar-nominated Palestinian film director Hany Abu-Assad’s Idol (2015) and Lebanese director Nadine Labaki’s Oscar-nominated Capharnaüm (2018). The most recent festival to draw international attention is Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Film Festival, which launched in 2019 in Jiddah but pushed its debut back to November 2021 due to the global pandemic. Its second edition is scheduled for the first week of December.

“The festivals did indeed foster a film community in the region, and they also gave exposure and opened up regional audiences to films from small but long-established film communities in, for example, Tunisia and Morocco,” says Jay Weissberg, former Variety film critic and senior film critic at The Film Verdict.com. “There is interesting work coming from these places that most (Westerners) don’t have access to.”

The festivals also made it possible for Arab filmmakers to meet each other, says Jordanian producer and screenwriter Nadia Eliewat, who was part of the award-winning Theeb creative team. She moved in 2016 from Jordan to Dubai in order to join forces with others in the industry.

“Such connections wouldn’t have been possible in Jordan,” she says. Networking in Dubai’s cinema circles led her to Lebanese music video director Sophie Boutros, who invited Eliewat to cowrite and produced Boutros’ 2013 directorial film debut, Mahbas (Solitaire), now available on Netflix. Eliewat also connected with Oscar-nominated Yemeni Scottish filmmaker Sara Ishaq, and she is currently producing Ishaq’s first feature, The Station.

Talal al-Muhanna of Kuwait, an independent documentary producer, says the Gulf film festival markets were the reason he decided to base himself in Kuwait, rather than the US or UK.

“Each time I traveled to film markets at the festivals, I would get pitched projects by filmmakers coming from elsewhere in the region and, importantly, from filmmakers in the Arab diaspora,” he says, explaining that many of the Kuwaiti filmmakers he now knows and works with regularly were people he met while attending regional film festivals.

Even by the 2000s, there weren’t yet many Arab films to screen at international film festivals, unless the Arab festivals helped produce them.

“In 2017 I was Head of Industry at that year’s edition of the Kuwait Film Festival, which allowed me the chance to translate all the regional networking I had done from 2008 onwards into invitations to the most important film funders in the region that were active at the time,” says al-Muhanna, who adds that some no longer are, such as Screen Institute Beirut, Enjaz, Doha Film Institute, Arab Fund for Arts & Culture, and MAD Solutions. “It was such a privilege to have all those organizations respond to the invitation to attend our event in Kuwait and pay forward some of what I had learned at other festivals over the years.”

The Rawi Screenwriting Lab, founded in 2005 in Jordan, has also proven broadly influential. An annual, five-day workshop for emerging Arab screenwriters scheduled each November, it has provided development tools for more than 100 students. Its mentorship program, which began in partnership with the Sundance Institute, the nonprofit host of the Sundance Film Festival in Utah, offered a premier platform to screen Haifaa al-Mansour’s 2012 feature film, Wajda, credited as the first feature movie filmed entirely in Saudi Arabia. In that country, young filmmakers have been making web series and short films ever since YouTube launched in 2005. Mahmoud Al Sabbagh of Saudi Arabia was part of this scene, and in 2016 he produced his first feature film, the romantic comedy Barakah Meets Barakah.

In recent years, Saudi Arabia has embraced film, lifted its ban on cinemas and is now encouraging filmmakers like Al Sabbagh to get connected and creative. Since 2018 it has displaced the UAE as the largest theatrical box office in West Asia, according to Comscore Media Measurement, a US-based media analytics company. Unlike in Dubai, where expatriate populations skew box offices toward Hollywood releases, Saudi Arabia’s top-grossing movie in 2021 was Waghfah Rajallah (A Stand Worthy of Men), from Egypt, and it was followed by two Egyptian comedies, Mesh Ana (Not Me) and Mama Hamel (Mom is Pregnant).

According to Comscore, Saudi Arabia is one of the only Arab countries where the number of movie theaters as well as theater attendance are both on the rise. As Egyptian films have historically found favor in the kingdom, the cinema revival and audience demand for more content could bode well for Egypt’s film creatives. It may also mean existing regional multiplexes will experience more traffic or that more theaters are constructed to cover underserved areas. Egyptian classic films are broadcast on satellite free-to-view TV across Egypt and can be watched on the Saudi-owned Rotana Classic channel, Rotana Cinema channel and the Egyptian-based M Classic channel, among others.

Arab filmmakers want to tell quality stories, beyond the Arab tropes and typecasts, and transcend geography and language.

The Dubai-based Shahid-MBC, an Arabic-content streaming platform launched in 2008, also streams new and classic films to its 27 million monthly viewers, among other options for prerelease and new-release films, documentaries, TV shows, and content for children. Shahid-MBC has recently started including international content with partner companies on its platform to appeal to an even wider market, but it faces competition from Bahrain’s Orbit Showtime Network, Amazon and Netflix, which are increasingly acquiring or coproducing Arabic language films for their platforms. Like the film festivals, streaming platform business models need constant new content to sustain.

“The platforms are great for small films,” says Eliewat, who underscores the opportunities they offer for independent producers. “They allow us to produce faster and finance faster.”

Eliewat is currently producing Yellow Bus, a drama directed by Abu Dhabi-based American Wendy Bednarz and coproduced with the India–based Sikhya Entertainment. It’s one of only about 25 films to be filmed in the Gulf that are about the Gulf.

“This is the first time the company has partnered with an Arab producer. It’s been an amazing exercise,” she says. “I think it’s something fresh and different coming from the Gulf region.”

While the UAE is producing the most Arab content, its financing and producing focus has been international. The Abu Dhabi and Dubai Film and TV Commissions offer attractive rebates and financial incentives for production companies to film in the Emirates, including Dune (2021), Mission Impossible 6: Fallout (2018), Fast and Furious 7 (2015), Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015), Mission Impossible 4: Ghost Protocol (2011), and Syriana (2005). Bollywood productions have also begun filming in the Gulf, and many of India’s major film stars now spend time in Dubai, including Shah Rukh Khan, who has appeared in more than 100 movies and is referred to as the “King of Bollywood.”

While making films in Kuwait, al-Muhanna is increasingly aware of how the Gulf region has become a crossroads for an exciting and expanding film and entertainment industry. More importantly, al-Muhanna says, Arab filmmakers want to tell quality stories, beyond the Arab tropes and typecasts, and transcend geography and language. They continue to fight for more funding and exposure, but they’re committed to making their mark and sharing their projects with the most globally connected audience the world has seen to date.

“In some ways, we are still playing catchup with more advanced filmmaking industries and economies in other parts of the world,” al-Muhanna says. “But there are such rich stories to tell from this region, and Arab filmmakers are not going away any time soon.”

You may also be interested in...

How 'The Journey' Anime Film Brought Saudi Stories To Life

Arts

The Japanese style of animation known as anime is underpinned with narratives of community, loyalty and collective purpose. Its ubiquity feeds a growing appetite for the art form, becoming popular in the Middle East.

Ithra Explores Hijrah in Islam and Prophet Muhammad

History

Arts

Avoiding main roads due to threats to his life, in 622 CE the Prophet Muhammad and his followers escaped north from Makkah to Madinah by riding through the rugged western Arabian Peninsula along path whose precise contours have been traced only recently. Known as the Hijrah, or migration, their eight-day journey became the beginning of the Islamic calendar, and this spring, the exhibition "Hijrah: In the Footsteps of the Prophet," at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, explored the journey itself and its memories-as-story to expand understandings of what the Hijrah has meant both for Muslims and the rest of a the world. "This is a story that addresses universal human themes," says co-curator Idries Trevathan.

Sami Katafi and The Legacy of 'Mi Amigo Angel'

Arts

By tackling often overlooked societal issues, Palestinian-born Sami Kafati’s body of work has shaped Honduran cinema even years after his passing.