Cheikha Remitti: The Voice of Rai Music In Algeria

Born in a village in northwest Algeria, Cheika Remitti sang high-energy songs of love, loss and society that pioneered rai music. Beloved by fans for more than 60 years until her death in 2006, her influence and popularity endure.

Her given name was Saadia, the happy one or one who is blessed in Arabic. It was a name that in time befit the singer who would later be hailed as Oum Rai, Mother of Rai and Queen.

On stage, Saadia Bedief went as Cheikha Remitti, and her more than six decades of performing before thousands could aptly be described as both happy and blessed. Throughout, Remitti never shed her identity as Saadia, who was born to a working-class family in Sidi Bel Abbès, in the village of Ain Thrid, about an hour south of coastal Oran in northwest Algeria. She inhabited Remitti, the queen, for decades. But her Bedouin lyrics were Saadia.

“Rai music has always been a music of rebellion, a music that looks ahead,” Remitti said in a 2001 interview on the radio program Afropop Worldwide.

It was she who from the 1940s led the development and popularization of rai, a uniquely Algerian folk genre rich with poignant, often raw lyrics about life’s everyday occurrences that in Arabic means opinion or way of seeing. Musically, rai blends influences from rural Algeria, Spanish flamenco and other sounds and song structures from around the Mediterranean.

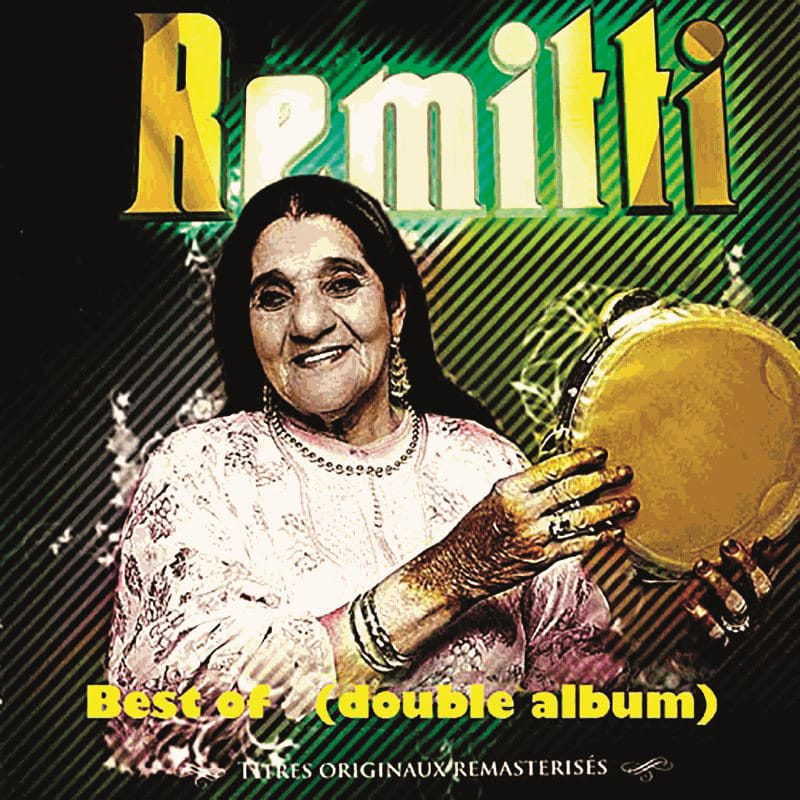

Remitti was a prolific songwriter even though, with no formal education, she never learned to read or write. She authored more than 200 songs, recorded some 400 cassettes and released 300 singles in her lifetime. When she died of a heart attack in May 2006 in Paris at age 83, she was still touring. Only two days before her last concert, she had released the album N’ta Gouda-mi (You Are in Front of Me), and she had performed to a packed audience of 4,500 at the Zénith Paris arena in the French capital. She appeared on stage as she always did, in a colorful, rural Algerian dress, adorned with jewelry, henna coloring both her palms and, on her feet, golden slippers.

More than 15 years after her death, Remitti’s music and resonant tenor voice is becoming popular again among younger audiences, particularly in France and Germany, with their large Algerian populations, as well as in Algeria. All are recognizing her songwriting as a canon that was ahead of its time.

“These female singers are only now getting the recognition they deserve,” says Algerian French visual artist Sofiane Si Merabet, who explores concepts of plural identities among North African diasporas in his artwork and digital platform, “The Confused Arab.” Remitti, he says, “was at the intersection of several universes, and I think it’s key to understand this about her and her music.”

Si Merabet, 39, comes from Relizane Province, where Remitti began her singing career, and he grew up listening to the Rai Queen. He recalls that at an early age, he discovered his grandfather’s videotapes of her performances, and he was warned the songs were too mature for children.

“I was told that I should not look at them,” he recalls. “Everyone listened to Remitti, but many people listened to her in private.”

Her songs represented the rural poor, a largely disenfranchised group in Algeria, Si Merabet says. Her lyrics reflected poverty with candor that could include stories about family hardship and more delicate matters of love, femininity, intimacy or drinking. Some considered her music too risqué, Si Merabet says, remembering that his parents, grandparents and others of older generations described Remitti’s music as vulgar or morally lax. Loyal listeners and fans appreciated Remitti’s lyrical honesty however, and they viewed her as a champion of women, the poor and, more generally, West Algerian Bedouin culture and social progress.

—Sofiane Si Merabet

“There were other singers and female singers also singing these songs, but they were not recording records or played on the radio, or later sung on a large stage,” says Si Merabet, who was born in France to Algerian parents and now resides in Dubai. “Remitti broke the glass ceiling by going public with the ailments and desires of the poor. No one had done this before.”

Remitti’s songs, which frequently begin slowly and gain tempo gradually, connected with listeners of similar socioeconomic backgrounds, Si Merabet explains. But today her songs resonate with broader audiences who appreciate her virtuosity and ability to not only sing, but also play the drum, or guellal, and gasba, a long wind instrument.

“She sang about love, passion, homelessness, hunger, but also about everyday things like pub fights, the advent of the telephone and car accidents,” says Si Merabet. She had a nearly photographic memory, never forgot a line or verse, and sang fearlessly about subjects many considered inappropriate for public discourse.

“Rai music has always been a music of rebellion, a music that looks ahead.”

—Cheikha Remitti

“She told me when she was young, she walked barefooted because her family was so poor,” says Nouredine Gafaiti, who acted as manager for Remitti’s career from 1986 to 2006 while also promoting other Algerian rai singers, including Cheb Hasni and husband-and-wife duo Cheb Sahraoui and Cheba Fadela.

Rai singers perform with cultural titles before their given name: Cheb is given to young males and cheba to young females. Cheikh and cheikha are given to older rai singers, men and women respectively. Remitti, who started singing professionally in her 20s, rather than performing as Cheikha Saadia, chose to protect her siblings—her parents died when she was a girl—from any possible hardship they may have experienced from her notoriety by changing her professional name to Cheikha Remitti Reliziana. Reliziana was often assumed to be her family name, but in fact was a reference to the city of Relizane, about an hour and a half northeast of Ain Thrid, where she began singing regularly for crowds.

Remitti, Gafaiti explains, was a variant of the French word remettre, to hand over, which she picked up on one rainy day of a local festival “when she bought an adoring crowd drinks, and they chanted ‘Pour some more!’” he says, adding that crowds responded enthusiastically to Remitti’s performances and songs from the beginning. It was not only her music’s honesty, her manager says, but also her confidence in who she was and from where she came.

“She remembers sleeping ‘rough’” for years before her singing career took off, Gafaiti says, explaining the measures Remitti would go to growing up to ensure she had enough money for food and shelter.

In the early 20th century, western Algeria was heavily populated by French settlers, and residents of villages like Remitti’s often found employment as seasonal workers at local distilleries. The region’s ample wheat fields and vineyards made alcohol available across urban and rural areas, an element mentioned in many of Remitti’s early songs. She also sang about her early transient years, moving from place to place to find work, laboring on citrus farms and sleeping in bathhouses, barns, and charitable soup kitchens adjacent to mosques.

Cultural anthropologist and University of Arkansas professor Ted Swedenburg, whose research includes rai music and Remitti’s songwriting career, says her music depicts historical themes of what Western Algerians experienced in the early decades of the 20th century.

“The music she sings … took its particular form from various sources, including the harvest seasons,” he says, noting seasonal workers employed by the French came from across Algeria to find work, and singing was part of everyday life. “Rai beats and lyrics were partially inspired during these agricultural seasons,” which were all the harder due to widespread disease, famine and land expropriation by French colonists.

Amid the hardship and uncertainty in her life, she could always retreat to singing and writing music. Her favorite singer was Cheikh Hamada, an Algerian performer from the coastal region of Mostaganem, about an hour northeast of Oran, who lived from 1889 to 1968. Hamada also played the guellal and sang traditional songs from the region in a genre known as badawi (Bedouin), which included the poetry of his forefathers and lyrics about celebrating Algeria’s “holy men” often honored by local communities. Remitti incorporated this storytelling style into her songs, but her lyrics often focused on life challenges, wisdom and advice from both her own experiences and those of women she met at the henna parties that often preceded weddings, as well as other celebrations and also at hammams. In these settings, frank talk among women often included matters of femininity, marriage, children, family and other personal, often intimate concerns. Over the years, these experiences and conversations became fodder for song.

After moving to Relizane in the 1940s, Remitti found regular gigs. While performing in the small city, she encountered seasonal Algerian travelers who visited regularly on local pilgrimages. At the annual festival there, Sidi Abed el Merja, which drew as many as 80,000 people to the city in the 1950s, Swedenburg says, Remitti introduced rai to Relizane, and its regular visitors eventually became her first fan base. Visitors also made the trek to listen to Remitti’s songs sung in the local western Algerian dialect.

“Our dialect is inspired by Bedouin Arabic, not like the people of Algiers, who have a completely different accent and pronunciation,” says Si Merabet, discussing Relizane’s Western Algerian culture. “This accent, this way of speaking Arabic sets us, including Remitti, apart regionally in Algeria.”

In this way Remitti’s style and subjects represented the culture and identity of a region frequently ignored in mainstream Algerian music.

“Her songs and the stories she sings are very local,” Si Merabet says.

Gafaiti agrees Remitti’s localisms helped draw continuous crowds to the city and to her shows. She helped normalize the region’s dialect through her music and introduce it to the wider Algerian population.

“Essentially, Remitti was a pioneer in making singing in local slang accessible on local radio stations and later on records,” Gafaiti says.

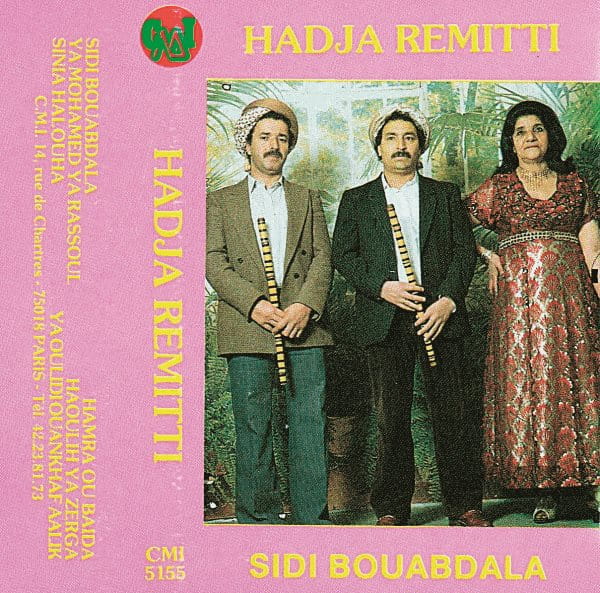

In 1952 Remitti released her first record for the Oran-based French label Pathé Marconi. Her debut single was “Ha-Rai, Ha-Rai” (Hey rai, hey rai).

While in Relizane, Remitti also met producer and classical musician Cheikh Mohamed Ould Ennems, whom she later married and with whom had three children.

She continued to play in private clubs and weddings, and she began traveling to France to perform, where she frequented the 18th arrondissement in Paris, where the North African neighborhood of Goutte d’Or and its Bedjaīa Club were a mainstay of Algerian rai singers. Yet in France Remitti did not experience the same level of celebrity as she enjoyed back home, and she traveled back and forth between the two countries for many years.

In 1971 she was involved in a car accident in Algeria that killed three accompanying musicians, and she was in a coma for several weeks. When she awoke her worldview abruptly changed: She adopted healthier life habits, and in 1976 she performed Hajj, the pilgrimage to Makkah, and briefly adopted the title it earned her: Hajeh Remitti. In 1978 she separated from her husband of more than 30 years and quietly moved to Paris. She continued to sing about love and poverty, joy and sadness in clubs across France. By 1986 most of her income came from performing at Algerian weddings throughout France.

“Remitti was a pioneer in making singing in local slang accessible on local radio stations and later on records.”

—Nouredine Gafaiti

“Not all Algerians celebrate their weddings with rai musicians performing. This is a purely Western Algerian tradition,” Si Merabet says. “My friends of Algiers express some outrage at this practice. They are more highbrow. But we Western Algerians enjoy celebrating our rural roots inspired by Bedouin and Amazigh heritage. We are proud, now more than ever, of this heritage.”

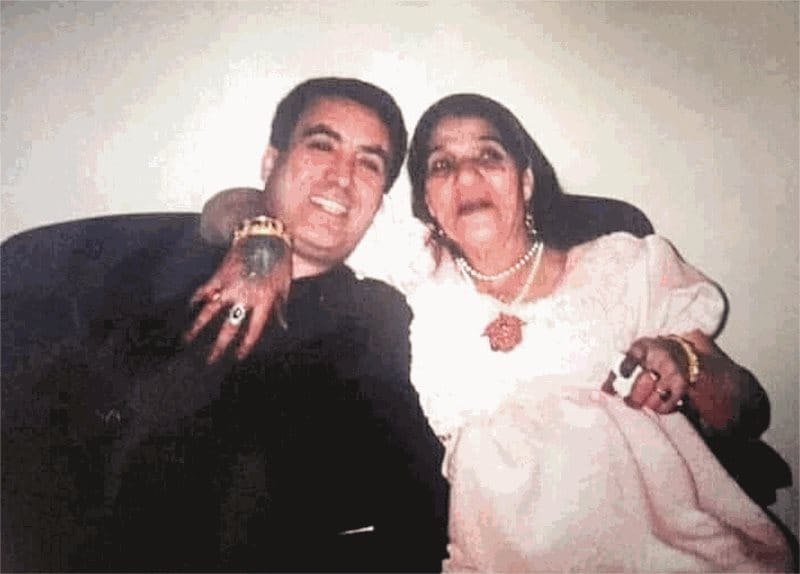

Gafaiti met Remitti in 1986 after her performance at France’s first Féstival du rai in the Paris suburb of Bobigny. She had performed alongside a little-known rai singer from Oran named Cheb Khaled, who later was popularly crowned King of Rai and became Remitti’s frequent royal singing counterpart. Cheb Khaled later crossed over also into French and Arabic pop, blues and jazz, and he is credited with adding a European flavor to rai. Still, everyone came after Remitti, says Gafaiti.

“She was the original rai singer. She was the founder. But others became more famous because they understood showbusiness,” he says. “She shunned it. She hated the press, especially the French press because they always wanted to sensationalise her. She resented that.”

In France Remitti was often characterized as too liberal and progressive, even though she was quite traditional in her private life. Remitti stood out as “other” among mainstream artists in part because of her rural upbringing and dialect, but more so because she was one of the first women to sing on the radio and in public about life’s intimate details. She was not alone in the discourse, however. Many female Bedouin singers before her sang and wrote songs about similar topics, Swedenburg says, but they did not perform in public.

“The publicity on Remitti was often misleading and mystifying,” he says. “European and especially French writers were making her out to be an anti-Muslim, antitraditionalist, pro-Western, feminist rebel.” That, he says, is inaccurate.

Swedenburg continues, “A lot has been written about Remitti being banned” in Algeria for being too controversial, which forced her into exile in France, but this too is not correct.

In the years following the 1954-1962 Algerian war of independence, the Algerian government promoted classical Arabic literature and music as socially desirable forms of art. Musicians outside classical genres, however—such as rai—were barred from radio and TV channels. This relegated rai in postliberation Algeria to private parties and the sale of cassette tapes on the black market.

Remitti’s international breakthrough occurred in 1994, when she collaborated with British guitarist Robert Fripp of the rock band King Crimson and US rock bassist Flea of Red Hot Chili Peppers. Together they recorded Sidi Mansour, produced and arranged by Houari Talbi in Los Angeles and Paris. The album included a new electric form of rai that is still influencing rising rai singers in Algeria and France.

Born in a Bedouin village in rural Algeria, Cheika Remitti sang high-energy songs of love, loss and society that pioneered rai music. Beloved by fans for more than 60 years until her death in 2006, her influence and popularity endure.

In the last decade of Remitti’s life, when she was in her 70s, her career began a meteoric rise. She was invited to perform in 20 European cities and several others including Tokyo. In 2019 the Paris City Council honored Remitti with her own public square in the 18th arrondissement, between rue de la Goutte d’Or and rue Polonceau. The sign in the square reads, “Place / Cheikha Remitti / 1923-2006 / chanteuse / pionnière du rai.”

Gafaiti was with Remitti in 2006 when she suffered a fatal heart attack. He remembers holding the singer in his arms in her final moments.

“The last words she said to me as she lay there on the floor were, ‘You are in front of me and I follow,’” Gafaiti says, mentioning her reference to the song, N’ta Gouda-mi.

Remitti was buried at the Cemetery of Ain Beida in Oran, the city where she recorded her first record and where her three children still reside.

“Remitti was a grand woman, a decent woman with an amazing story,” says Gafaiti. “She was a real Bedouin woman.”

About the Author

Mariam Shahin

Filmmaker and writer Mariam Shahin has produced and directed more than 70 documentary films, and she is author of Palestine: A Guide (Interlink Books, 2005) and coauthor of Unheard Voices: Iraqi Women on War and Sanctions (Change, 1992).

Matthew Bromley

Artist, illustrator and publication designer Matthew Bromley runs Graphic Engine Design in Austin, Texas, and he is the graphic designer of AramcoWorld. Contact him at mbromley@graphicengine.net, @robot.matthew.bromley on Instagram.

You may also be interested in...

Sitar Master of Maryland

Arts

With a lifetime of training from leading sitar virtuosos, Alif Laila is one of few women to achieve international recognition with the mesmerizing instrument whose sound evokes the musical identity of the greater Indian subcontinent. She is as passionate about music as she is about encouraging other women.

Prince of Enchantment: The Oud

Arts

Often regarded as the forerunner and name- sake of the European lute, the ‘ud (oud), is among the world’s oldest continuously played string instruments. In Arab and other musical traditions, its deeply resonant, emotionally evocative tones earned it, over the centuries, the sobriquet amir al-tararb.

Alaa Zouiten's 'Flamenco Arabe' Urban Jazz Finds Home in Berlin

Arts

Culture

A musical wave has been swelling for a decade in the German capital, which one local analyst now calls "the city of choice for a new generation of cultural talent from the Middle East and North Africa"—part of the greater demographic shift that has made people of Arab backgrounds Berlin's fourth-largest ethnic-identity group. In street jams, clubs, studios, concert halls and online, new mixes of musicians are blending notes and ideas into genre-bending, transcultural fusions. "What we as artists in Berlin can do is tear down the borders in our head and invite others to do the same," says musician Jamila Al-Yousef.