The Meaning of Henna and Its Rise in the West

The smell of eucalyptus and lavender oil mingles with the earthy aroma of henna paste lingering in the room. Jaya Robbins’s hands, already stained with henna on the tips, carefully pour a freshly made paste into a plastic pastry bag atop a large cup covered with a single pantyhose sock.

After adding all the ingredients to a large bowl, Jaya Robbins mixes with a spatula—a process that can also be done by a stand mixer. The paste is then covered with plastic wrap and placed in a warm area for 6-8 hours to allow for effective dye release. The paste is mixed again until it reaches a smooth and stringy consistency, as seen above.

The smell of eucalyptus and lavender oil mingles with the earthy aroma of henna paste lingering in the room. Jaya Robbins’s hands, already stained with henna on the tips, carefully pour a freshly made paste into a plastic pastry bag atop a large cup covered with a single pantyhose sock.

Robbins picks the bag up, lightly twists and holds it at the top and carefully pulls the sock out of the bag, ensuring the paste is filtered through. These steps are merely a portion of Robbins’s daily routine that she has perfected to make and package fresh henna-paste cones for her business.

Robbins, a professional artist known as Gopi Henna, started 11 years ago when she visited India and saw henna cones for sale at a local store. She recalled her love for the bridal henna she had just seen at her own wedding months before, so she picked up the cones, and the experiments were initiated.

“It’s kind of funny because the first time I ever did it, I immediately washed it off because it was so bad. But I really loved it because it was similar to cake [decorating],” the former cake decorator laughs.

Robbins believes the mark of a master henna artist is having patience, “working at it, trying to learn” and understanding the value of a media presence to build online brand legitimacy. She often posts how-to and behind-the-scenes videos of equipment and designs on social media, including YouTube and Instagram, and has garnered a reach of more than 750,000 subscribers and close to half a million followers, respectively.

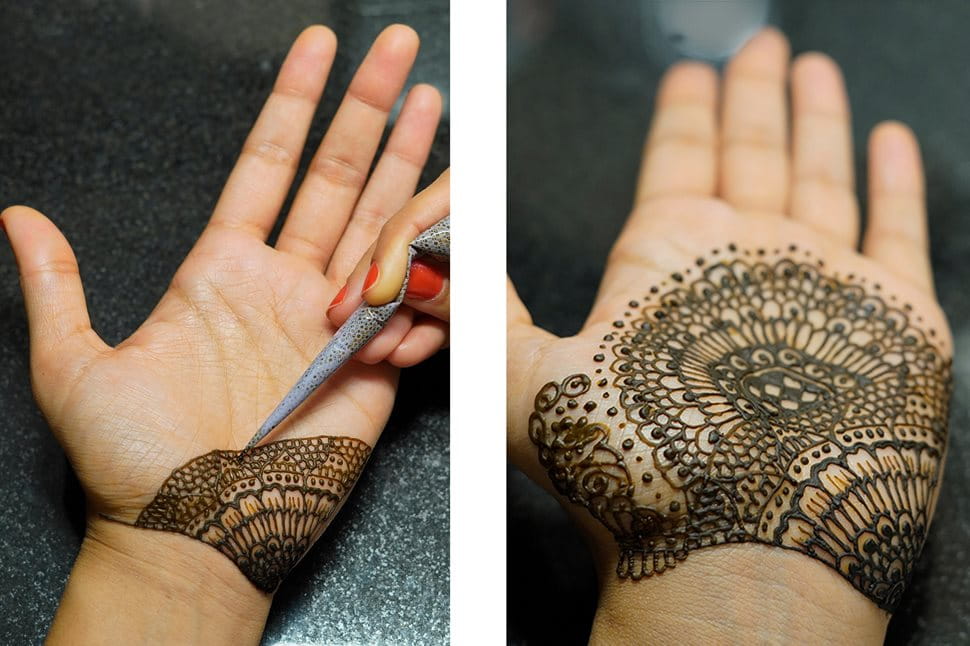

For best results, henna should typically stay on the skin for at least four to six hours. After scraping off the dried henna paste, avoid washing the area with water for up to a day to allow the stain to develop fully, which can take 24 to 48 hours.

“If you have the right attitude, I think doing henna is also more than just the art itself,” Robbins says. “I feel like anyone can start, but there also has to be a good intention.”

What is henna, and where does it come from?

For Los Angeles-based henna artist Niru, applying henna for friends nearly 10 years ago helped her earn her first income as an immigrant to the US.

Henna, or Lawsonia inermis—a name given in the 18th century by the father of modern taxonomy, Carl Linnaeus, according to the Natural History Museum—is a large shrub or small tree that can reach 20 feet (6 meters) in height. Its white and dark pink flowers are used to make essential oil and perfume. But the plant is best known for the dyeing quality of its leaves; their paste is used in intricate designs that adorn the hands and feet of those seeking beauty and blessings in weddings and other celebratory occasions from South Asia and the Middle East.

St. Thomas University-New Brunswick cites that the plant has maintained its status as one of the most recognized and utilized in the world for more than 5,000 years. Henna’s safe dyeing and medicinal properties—topically on all parts of the body—have helped it endure in the Eastern Hemisphere and now experience a surge in popularity in the West for the same reasons.

Among the names used by different cultures for henna, the most well known is the ancient Arabic name hinna or henna. According to the book Henna’s Secret History: The History, Mystery & Folklore of Henna, the name was believed to be given to the plant by Arabic-speakers in Persia—even though the plant doesn’t have ties to that region otherwise.

It is hard to tell when henna was first used. To Maham Sewani, a guest lecturer on “The Art of Henna” at Rice University in Houston, Texas, there has been a lack of attention to the plant’s history from an academic perspective, specifically on its origin.

"Henna design styles vary: (clockwise starting top left) Moroccan patterns are known for their bold and symmetrical lines and patterns; Saudi Arabian designs emphasize precision and include stained tips; other North African designs feature geometrical elements and linear decorations; and Indo-Pakistani styles incorporate detailing with a blend of floral motifs, paisleys, vines and lacelike craftsmanship.

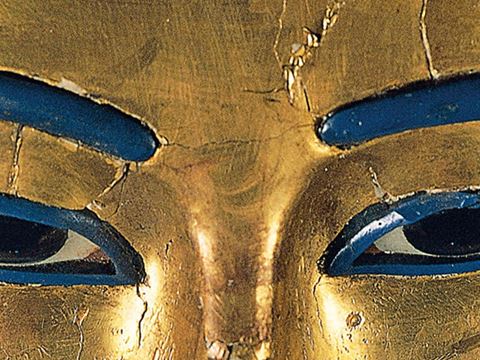

“The general consensus is that there is no consensus,” Sewani shrugs. “The best guess is ancient Egypt [as] it was used to dye mummy wrappings.”

The Egyptians never spoke of importing henna from anywhere outside the region, but in her book Henna’s Secret History, author Marie Anakee Miczak mentions the Egyptians appeared to have a long time to experiment with the botanical. Their experience with producing wet chemistry and advanced medical techniques could have allowed them to discover henna’s medicinal qualities, including cooling, being antifungal and providing protection from ultraviolet rays, which is especially helpful in hot desert climates.

Eleven years into the craft as a professional artist known as Gopi Henna, Jaya Robbins believes the mark of a master henna artist is having patience, “working at it, trying to learn” and understanding the value of a media presence to build online brand legitimacy.

A 2012 research paper by the Department of Chemistry at Savitribai Phule Pune University in Pune, India, went further and found that henna extracts “possess numerous biological activities including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and anticancer” qualities, and yet the “compound has remained largely unexplored.”

What is certain is that henna was documented as an Egyptian remedy for headaches and heat prostration, as used by pharaohs. A 2023 paper published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences and Criminal Investigation mentions that henna also includes lawsone, a burgundy dye molecule, which can provide a red-orange color “when it interacts with keratin in the skin, nails and hair.”

Since 3400 BCE, many Egyptians stained their natural hair, wigs and hair weaves with henna for that reason, while pharaohs dyed their beards. And many countries in South Asia and the Middle East to this day often use henna for bodily designs and hair dye, including Afghanistan, Algeria, Bangladesh, Egypt, India, Iran, Malaysia, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan and Tunisia, according to the publication Bayt al Fann.

Henna in the West

For Argentinian artist Natalia Zamparini, henna’s origins are like that of any other element.

“A lot of people don’t even know henna connects to places where henna doesn’t grow due to cultural displacement,” Zamparini says. “I think an older generation has a lot of pride and ownership and doesn’t realize that it actually might trace back a little bit older than their own culture elsewhere. … It’s a constant education and re-education.”

Freshly made henna paste is often strained and dispensed into rolled cellophane sheets and closed with tape. Each henna cone is then carefully weighed and packaged to ensure quality on behalf of the seller.

Growing up in the borough of Queens in New York in the 1990s, Zamparini was part of the change. She saw her neighborhood incorporate Indian, Guyanese and Trinidadian demographics—some of her classmates who had henna on their hands exposed her to henna for the first time, piquing Zamparini’s interest to widen her graphic design scope and include the application of henna as body art.

Also known as NatybyNature, Zamparini is in her 15th year as a professional henna and tattoo artist. Yet as someone who is not of South Asian or Middle Eastern descent, Zamparini finds her clients from those respective backgrounds often “try to place where she’s from” and educate her on how the art originated from and is used in their regions.

The word henna is often used interchangeably with its plant and body-art forms. Henna, which stains on the skin, fades away within a couple of weeks, which also adds to the allure of being a temporary tattoo. Further evidence of expanding interest in henna can be read in a 2024 report by DataHorizzon Research, which shows that the value of the henna powder market size is expected to double in less than a decade. Experts argue that’s mostly because there is a growing interest in natural dyes.

Beyond South Asian and Middle Eastern events, Western henna artists are increasingly in demand for celebrations they otherwise had not been hired to work before. For Niru, a Los Angeles artist known by the name Hollywood Henna, her business has been invited to bridal and baby showers, birthday parties, henna booths at product launches and quinceañeras—celebrations for a girl’s 15th birthday and transition to womanhood in Mexican and Latin American cultures—all progressively over the past nearly 10 years.

“The shift that I’ve seen is that everybody’s more educated about henna now—they are learning about it, they are embracing it,” Niru says. “They ask you, ‘Is it OK if we apply henna? Is there a cultural appropriation associated with that?’ And something that I always tell them [is] that there is no such thing. It’s not limited to a particular country or a particular region: It’s available to everybody because it’s out there in nature.”

As both a lecturer and henna artist, Sewani also shares an optimistic view on the expanding popularity of the plant because of social media platforms. “I think the future of art in general is just going to be a battle of automation and artisanship. But hopefully, globalization and sharing cultures bring a unique appreciation to people.”

The art of henna

Henna artists say they draw inspiration from a variety of sources, blending cultural heritage with contemporary influences to create meaningful designs. Many artists begin with motifs and designs passed down through generations, such as paisleys, mandalas and floral elements. Nature often serves as a muse, with leaves, flowers and vines intricately woven into the work. Additionally, modern henna artists incorporate personal experiences, emotions and the world around them. And that journey is unique for each artist.

For Niru, the spark to become a henna artist was ignited when she was a kid experimenting on her mother’s hands as her mother slept.

“I would make [the design] beautiful the entire night. I used to … make mountains, people or anything.”

She says she earned her first income from henna art as an immigrant from India. “This is something that guided me. I didn’t guide henna; henna kept on guiding me through this journey,” she says.

Creating a smooth and effective henna paste requires mixing the basic ingredients of natural henna powder with lemon juice, sugar and essential oils to ensure a darker stain.

Beyond the art

The landscape has expanded its beautification practices. Paisleys and other henna designs are now seen adorning clothing and graduation sashes. Even for the body, beyond requests for henna on the hands, arms and feet, there are uses of hair dye and freckles and requests to cover up scars, embellish the bellies of expecting mothers and apply paste on crowns for those who have lost their hair.

“I felt like I wasn’t contributing something positive to the world,” Zamparini recalls of the time before she pursued henna as a full-time business. “Here showed up henna again, which actually became a magnet and icebreaker for conversation, which was really therapeutic.”

Robbins admits artists like herself already put a lot of pressure on themselves to create good work for a customer since the person is trusting them with a design on their body, be it temporary.

“Maybe there’s something to it: Maybe I am able to offer an experience that people enjoy and be able to serve in that way on someone’s special day. …That’s what I love about henna.”

Each design is more than just an embellishment; it’s a symbol of joy, celebration and cultural identity, woven together in a tapestry of tradition.

You may also be interested in...

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.

How Azza Fahmy's Jewelry Blends Egyptian History and Art

Arts

Azza Fahmy has become a legend in the world of artisanal jewelry from the Middle East. Her designs, now some of the most sought after in the Arab world and internationally, have long championed the history and culture of Egypt and the greater region with contemporary style, forms and vision—often with references to Pharaonic symbolism, Mamluk architecture, Egyptian modernism and vernacular cultures.

Pretty and Protective: Egyptian Kohl Eyeliner

History

Arts

Science & Nature

The black eyeliner known widely today as kohl was used much by both men and women in Egypt from around 2000 BCE—and not just for beauty or to invoke the the god Horus. It turns out kohl was also good for the health of the eyes, and the cosmetic’s manufacture relied on the world’s first known example of “wet chemistry”—the use of water to induce chemical reactions.