Brill’s Bridge to Arabic

It started out as many successful businesses do: with a bit of vision, a prime location and some family connections. From its first Arabic text in 1732 to today, Brill’s books helped build the scholarship of what is today broadly called Middle East and Asian studies.

Amsterdam’s 1883 International Colonial and Export Exhibition was a lavish, five-month celebration of Dutch colonialism and capitalism that drew more than a million visitors from around the world. Still, Amin ibn Hasan al-Halawani al-Madani al-Hanafi, who had traveled all the way from Cairo, was disappointed.

Amin ibn Hasan al-Halawani al-Madani al-Hanafi, known in the West more simply as al-Madani, visited Leiden in 1883, by which time the city’s reputation as Europe’s leading center for the study of Arabic had been long established. Brill bought a large collection of his collected manuscripts.

Muslim jurist and part-time book dealer, al-Madani (as he was known in the West) had come in hopes of selling a large collection of manuscripts amassed during his travels throughout the Islamic world. Sitting alone at his exhibition table, he failed to interest a single passerby. That was, until he bumped into an acquaintance, Count Carlo de Landberg, a Swedish aristocrat and scholar of Arabic. He suggested al-Madani try talking to E.J. Brill, a publishing house in the nearby city of Leiden.

The Count’s tip paid off. Not only did Brill’s editors arrange for Leiden University’s purchase of his entire, 600-volume collection, they accommodated him like a minor celebrity, feting him about town and introducing him to the local intelligentsia, who invited him to the Sixth International Congress of Orientalists in Leiden. There, as the lone Arab among some 300 European Assyriologists, Egyptologists, Arabists and the like, al-Madani was impressed at their mastery of Arabic and their passion for Arabic literature.

Their expertise was no coincidence. By the time of al-Madani’s visit, Leiden’s reputation as Europe’s leading center for the study of Arabic was long established. From the late 16th century, philosophers, theologians and linguists from across the Netherlands and Western Europe had flocked to the university in this handsome little Dutch city, about a half hour by car or train southwest of Amsterdam. Laboring with what Arabic manuscripts they could get their hands on, these scholars “revolutionized the study of Arabic,” says Alastair Hamilton, co-director of the University of London’s Centre for the History of Arabic Studies in Europe, and “assembled one of the very best libraries of Arabic works in Western Europe.”

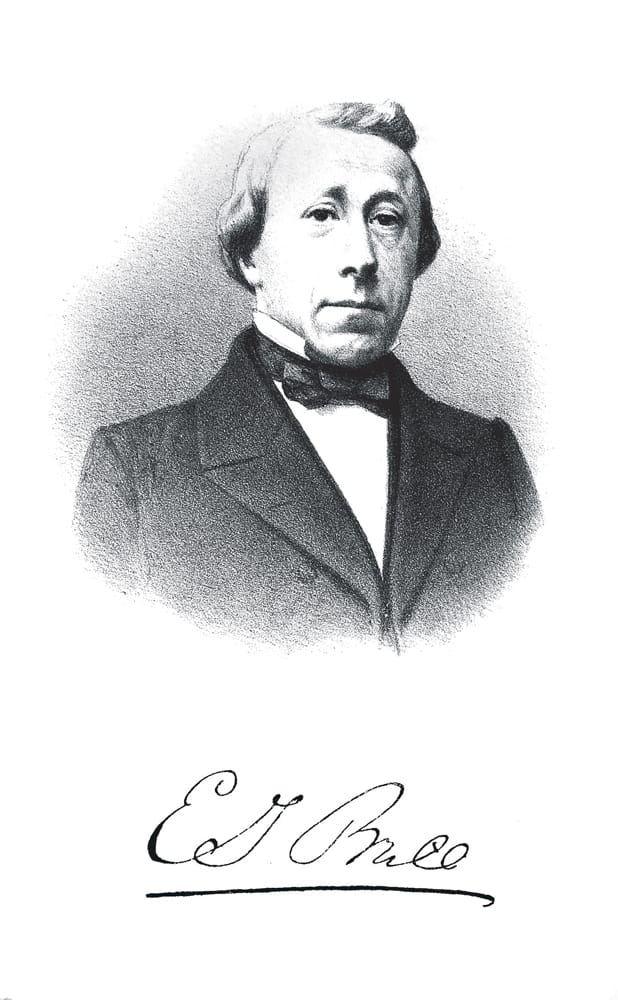

In 1849, the bookshop passed to Evert Jan Brill, who ran it until his death in 1871. In the same year al-Madani visited, the firm moved to this building, which, although it is today a block of apartments, still carries the company name.

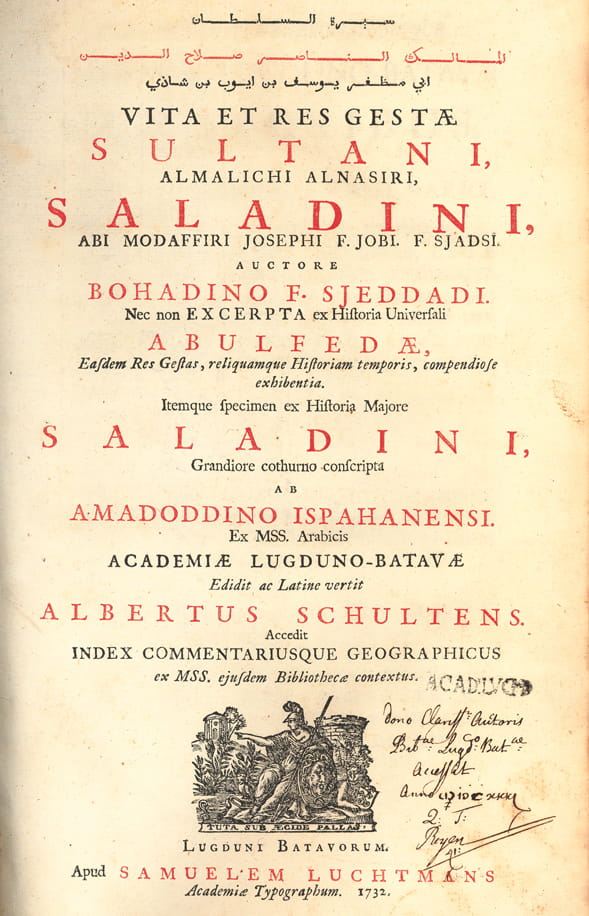

From two centuries prior to al-Madani’s visit and continuing up to the present day, the centers of this intellectual activity have lain not only at Leiden University, but also with the firm of Brill, the oldest publisher in the Netherlands and among the oldest in Europe. Through wars, empires and economic booms and busts, Brill has decorously endured. From its very first Arabic text, published in 1732—an edition of Ibn Shaddad’s 12th-century biography of Saladin—to its monumental, ongoing Encyclopedia of Islam, Brill has brought to Western scholarship hundreds of works that undergird the entire fields of Arabic and Oriental studies. And it all began as many businesses do: with a bit of vision, a prime location, and some family connections.

As the location, from 1575, of Leiden University, the fashionable Rapenburg Canal has long been the city’s intellectual hub and, at one time, its publishing center. Having shaken off the yoke of Spanish Catholic domination during the Eighty Years’ War (also referred to as the Dutch War of Independence, 1568-1648), the assertively Protestant city became known as a haven of religious tolerance, scientific innovation and unfettered thought. It was in Leiden that a group of English émigrés found refuge before setting sail for the New World on a ship named Mayflower; where in the university’s medicinal garden Europeans first cultivated tulips, which had come as a diplomatic gift from the Ottoman court; and where the works of Galileo and Descartes (whose address for a time was Rapenburg 23) could be published in defiance of papal censors.

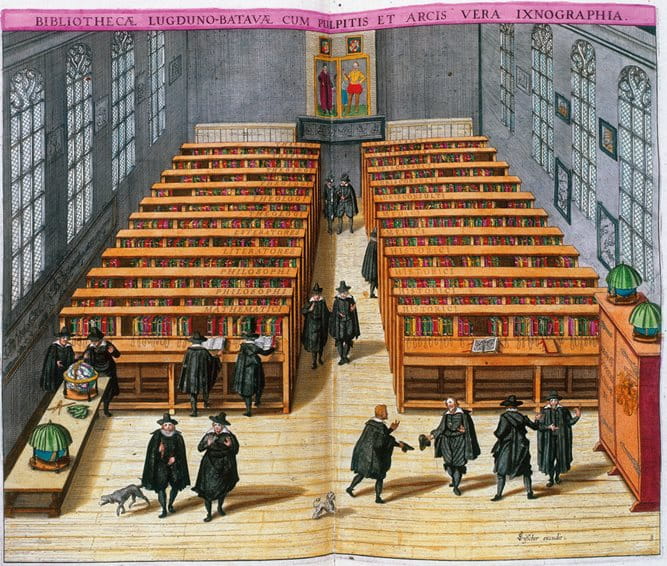

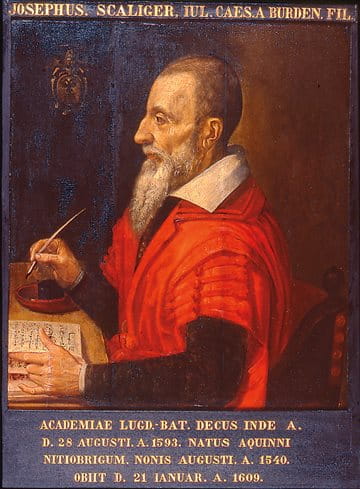

In this 17th-century depiction of Leiden University’s library, at bottom right appears the Arca Scaligerana, a cupboard that held more than 300 printed works in Arabic, Hebrew and Ethiopian. Donated by Arabist and humanist Josephus Justus Scaliger, below-right, the collection not only was seminal to the study of languages and literature at the university, but also reflected Scaliger’s own ideas that Arabic was best studied neither as a commercial nor a religious tool, but rather as another path to knowledge.

Brill’s roots reach deeply into this past. In 1683, a 31-year-old bookseller named Jordan Luchtmans registered with Leiden’s book sellers’ guild and apprenticed in both Leiden and The Hague before opening a shop in 1697 at No. 69B Rapenburg. Some 150 years later, his business would become Brill. His location, next to the Academiegebouw, the university’s main academic building, was known as “the realm of Pallas,” after Pallas Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, whom Luchtmans paired with Hermes to adorn his colophon, which today remains Brill’s. Luchtmans’s wife, Sara van Musschenbroek, descended from intellectuals and publishers including Christoffel Plantijn, printer to Leiden University and the famed publisher of one of the earliest polyglot (multilingual) Bibles, which he printed in one Hebrew, Latin, Greek, Aramaic and Syriac edition.

The broader European interest in Arabic and other “Oriental” languages at the time was in part commercial, for they were useful in the Asian and Indian Ocean spice trade that was dominated by the world’s first multinational corporation, the Dutch East India company. For others, Arabic was a key to Biblical Hebrew; still others saw Arabic as a tool for Christian missionaries.

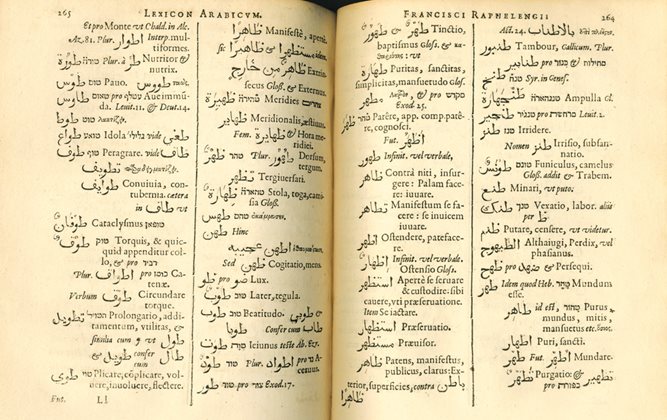

In Leiden, another motive had taken root: Arabic as a window to knowledge and wisdom. Some of the university’s earliest professors of Arabic included, in the latter 16th century, Franciscus Raphelengius, who was also Europe’s first printer of Arabic outside of Rome, and Josephus Justus Scaliger, who stressed that true knowledge of Arabic must begin with its sacred text: “You can no more master Arabic without the Qur’an than Hebrew without the Bible,” he wrote.

Europe’s first Arabic-Latin dictionary, Lexicon Arabicum, appeared in 1613, written by Europe’s first printer of Arabic outside of Rome, Franciscus Raphelengius.

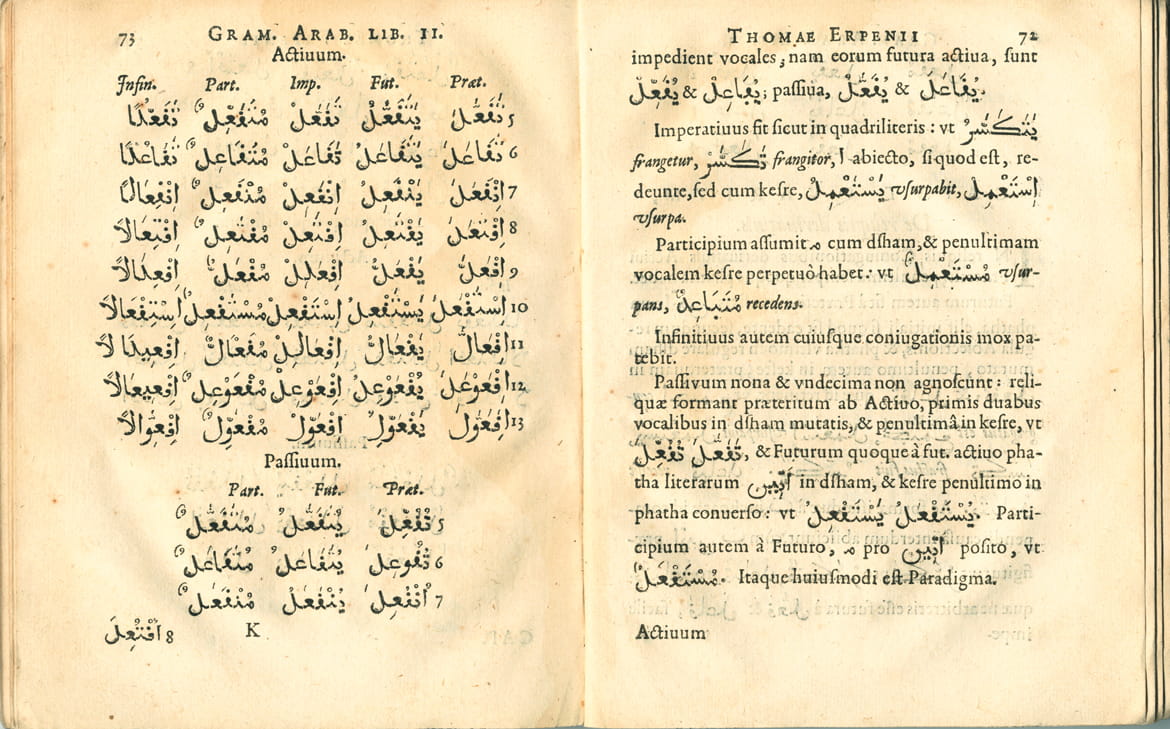

From his Rapenburg shop, Luchtmans responded to this scholastic interest by systematically publishing works hitherto unknown in the West. These included, among others, manuscripts from the university’s famous Legatum Warnerianum, a collection of more than 900 historic documents in Arabic, Persian, Ottoman Turkish, Hebrew, Greek and Armenian, as well as the Grammatica Arabica by Leiden University’s first chair of Arabic, Thomas Erpenius. In Arabic Studies in the Netherlands in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Hamilton observes how Erpenius’s’ Grammatica remained the standard manual for the study of the language for two centuries, and ”even when it was superseded in the 19th century,” Hamilton notes, it “was still the model on which later works, including the present standard Arabic grammar by William Wright, were based.”

Over the next three-quarters of a century, generations of Luchtmans continued to seek out and publish books on the languages, literature and history of the Middle East and Asia. As the university’s official printer, the firm’s symbiotic relationship with the school enabled Leiden professors to easily publish research in the emerging academic fields of Egyptology, Assyriology, Indology, Sinology, Persian and Arabic studies.

By 1848, the last Luchtmans descendant to run the firm, the professorial J. T. Bodel Nijenhuis, retired to pursue his academic interests. The family and its sundry partners sold the business to the man they considered the most fitting heir: Evert Jan Brill.

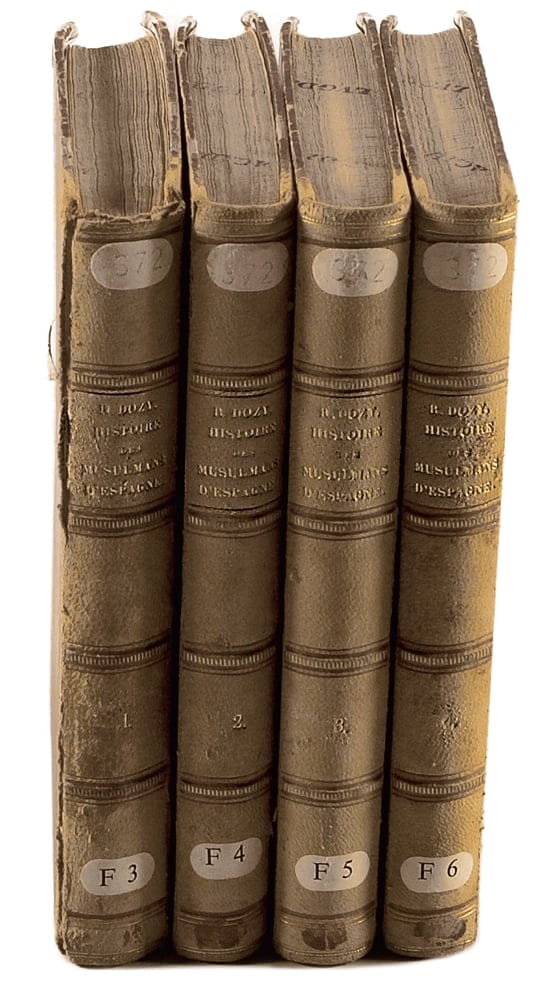

Brill’s family had worked for Luchtmans publishing since 1802. Evert well understood its day-to-day operations, and he shared the company’s dedication to Arabic and Oriental studies. Under the firm’s new, eponymous name of E. J. Brill, he courted top writers, such as the Arabist and Al-Andalus specialist R. P. A. Dozy, whose Histoire des Musulmans d’Espagne, published by Brill in 1861, remains a standard history of Moorish Iberia.

Perhaps even more significantly, Brill expanded the number of scripts and typefaces in his publishing repertoire: In addition to Arabic, he published Hebrew, Aramaic, Samaratin, Sanskrit, Coptic, Syriac, Persian, Tartar, Turkish, Javanese, Malay, Greek and several of their variants. From 1866-69, he rolled out the multi-volume Études égyptologiques (Egyptian studies) by Willem Pleyte, director of Leiden’s National Museum of Antiquities and a member of Brill’s own board of directors. This required not only Egyptian hieroglyphs but also hieratic, the script used for millennia by Egypt’s priestly class—yet one more of the exotic, specialized typefaces that made Brill the world’s top publisher for the most arcane and eclectic selection of texts both in and about Oriental and Middle Eastern languages.

“They excelled in printing in Oriental languages,” says Kaspar van Ommen, coordinator of Leiden University Library’s Scaliger Institute, “and they still, up to this day, remain one of the few publishing houses that can print in hieroglyphic, in Urdu, in Batak and in all these strange Oriental typefaces.”

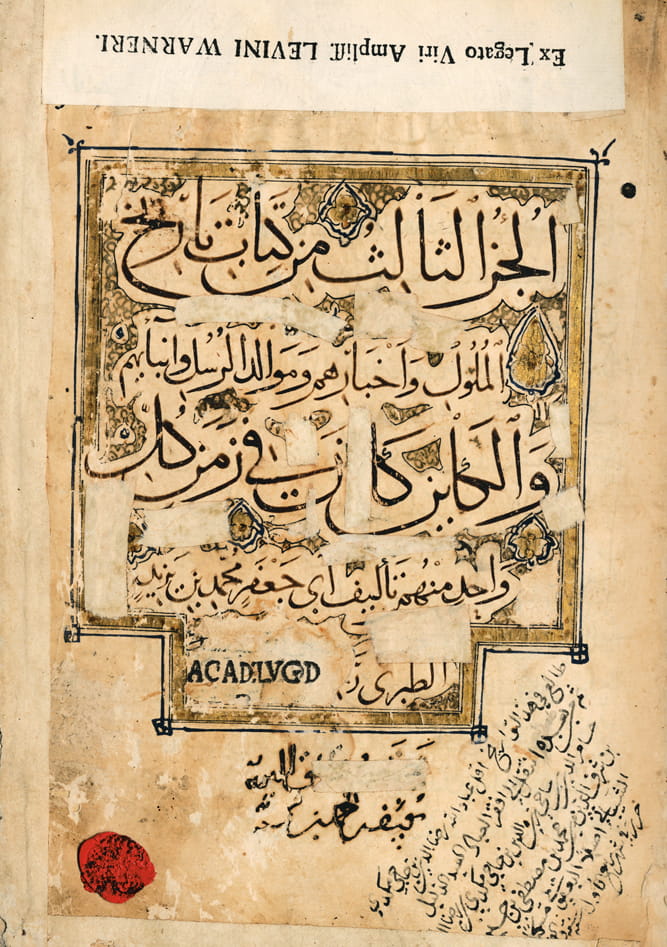

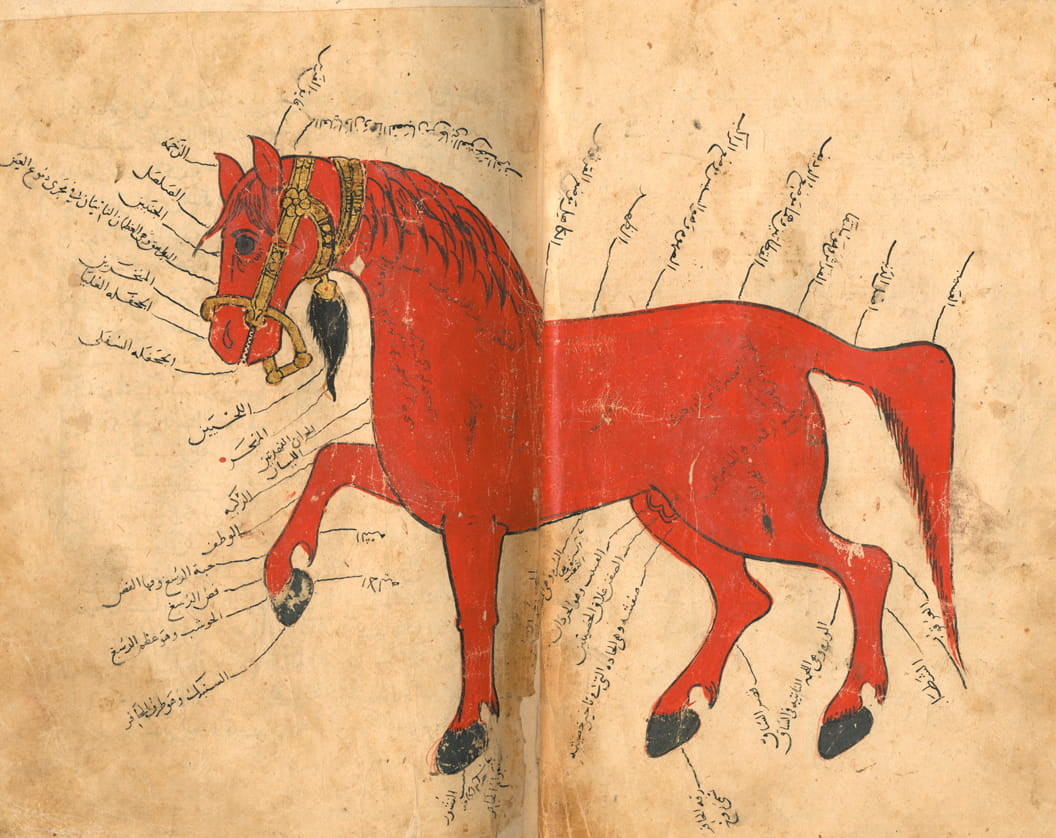

Brill himself died in 1871, aged 60, but his successors carried on and began to recruit more and more foreign scholars, too. The 16-volume Tarikh al-Rusul wa al-Muluk (History of the Prophets and Kings), a ninth-century history of the Middle East by Persian historian Abu Ja’far Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, was published between 1879 and 1901, and required the efforts of 14 Arabists from six countries. Directing them was a pupil of Dozy’s, Leiden professor M. J. de Goeje.

De Goeje’s own star pupil was another Leiden professor and Brill author, Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje, who became a Muslim and, shortly afterward, spent a year between 1884 and 1885 in Makkah. There, he wrote a two-volume historical and ethnographic study of the city. Together with two books of some of the earliest photographs from the Holy Cities, Hurgronje’s writing provided scholars a wealth of new, detailed information on all aspects of the Hajj—especially pilgrimages from the former Dutch colonial possessions in what are now Indonesia and Malaysia.

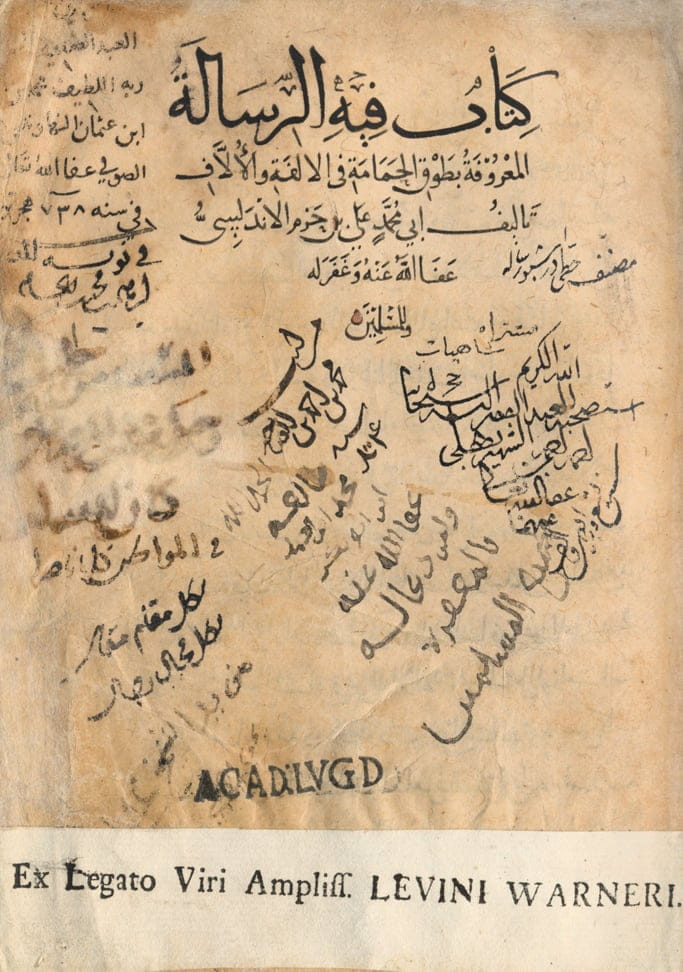

Leiden University’s preeminence in Arabic studies arose from its scholars’ interest in seminal, often complex manuscripts that Luchtmans, and later Brill, also committed to publishing. After the Scaliger donation, one of the largest collections given to the University came from Levinus Warner, who lived some 20 years in Constantinople in the 1600s. His Legatum Warnerianum (Warner Legacy) holds such rare publications as ibn Hazm’s Tawq al-hamama (The Ring of the Dove) from the early 14th century, left, and the third volume of the ninth-century The Annals of Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, right.

By 1883, the year of al-Madani’s visit, Brill had outgrown the Rapenburg bookshop, and it remodeled a former orphanage at 33a Oude Rijn (“Old Canal”). Massive granite lintels on the four-story building’s brick façade still display the towering inscriptions in capital letters, “E.J. BRILL” and “BOEKHANDEL EN DRUKKERIJ” (bookstore and printshop), even though the building today is an apartment complex. Technologically cutting-edge at the time, the “shop” was more like a factory, with a pair of steam-driven elevators to haul bundles of paper and other materials to the upper floors.

At the turn of the 20th century, Brill no longer operated as the university’s exclusive printer. In 1896 it had become a publicly traded company, and it was experiencing unprecedented growth. Many investors met with Brill’s directors in the nearby Den Vergulden Turk (The Gilded Turk), a building whose elaborate tympanum sports a bust of a “Turk” in a gold turban, symbolizing the city’s long-standing commercial interests in the East. In the early decades of the 20th century, the company published some 450 titles—three times as many as had E. J. Brill in his own lifetime; it also expanded its academic journals. “Scholars in all quarters of Europe, in Asia and in America were familiar with the name of Brill and knew the way to the Oude Rijn,” writes Sytze van der Veen in his 2008 history of the company, Brill: 325 Years of Scholarly Publishing. Brill was also increasingly familiar with, and reliant on, the firm’s magnum opus: the Encyclopedia of Islam, the seeds of which were sown at the end of the 19th century and which are growing still, well into the 21st.

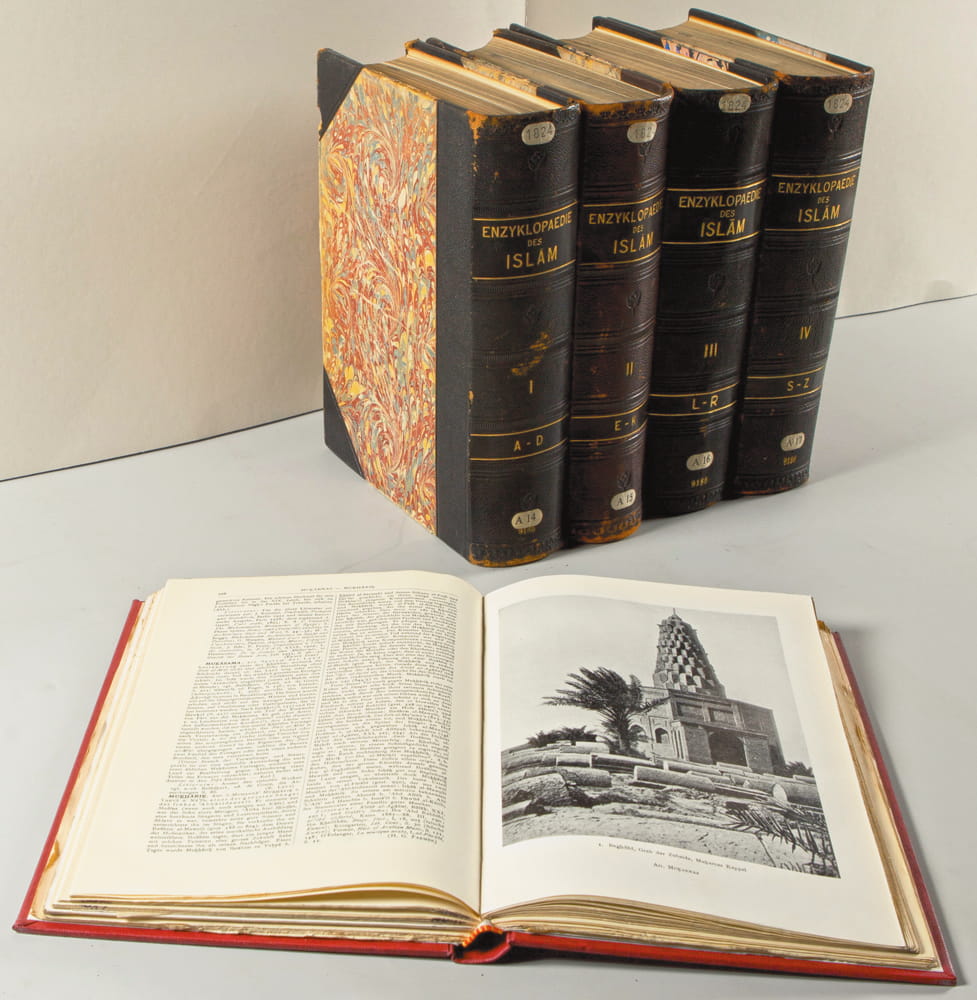

The multigenerational academic project, suggested by Encyclopedia Britannica editor William Robertson Smith, aimed to produce a reference work that would “contain all the available knowledge about the languages, cultures and religions of the Islamic world,” notes Arnoud Vrolijk and Richard van Leeuwen in their catalogue to last year’s exhi-bition, “Excellence and Dignity: 400 Years of Arabic Studies in the Netherlands.” Modeled on Germany’s 80-volume Encyclopedia of the Ancient World, the Encyclopedia of Islam was planned with a focus on philological themes like law, politics, literature and history, with entries contributed by an international team of Western scholars.

At the helm was chief editor M. Th. Houtsma, then a professor of Eastern languages in Utrecht, but behind the scenes, the indomitable de Goeje did his share of the heavy lifting. And the task required plenty of intellectual muscle, not to mention patience. Houtsma was appointed in 1899; nine years later, the scholars had only just made their way through the letter “A.” Picking up a bit of steam, they bound the first volume—“A-D”—in 1913. World War i came and went, and it was not until 1936 that Brill published the full, four-volume edition in the three scholarly languages of the day: German, English and French. Packed within its 5,042 pages were more than 9,000 entries ranging in length from 50 to 50,000 words, many of which continue to impress and be of use to scholars to this day.

Yet as monumental and groundbreaking as it was, ultimately the Encyclopedia of Islam was what it was: a Western body of work by Western scholars on the Islamic world, tempered in an age of Orientalism. As such, writes scholar R. Stephen Humphreys in his 1991 study, Islamic History: A Framework for Inquiry, it “represented a specifically European interpretation of Islamic civilization.” It was not, Humphreys concludes, “that this interpretation is ‘wrong,’ but that the questions addressed in these volumes often differ sharply from those which Muslims have traditionally asked about themselves.”

After World War ii, Brill editors recognized the need for revision, and they began planning a second edition. While many entries remained the same or only slightly altered, the editorial and writing team now included Muslims, notably from Egypt and Turkey. This, Humphreys observes, produced a “change in tone” that was “perceptible and significant” between what were now being called EI1 and EI2. Meanwhile, the editors of EI2 were even more giddily optimistic about the time and amount of work required to complete their project than had been the EI1 team: They predicted the first volumes would hit the shelves in 10 years. The job took more than half a century.

During that time, from the 1950s to the turn of the 21st century, scholarship, methods, identities and ways of thinking all changed dramatically. Nations emerged from colonial pasts into the complex and variegated independent present. It was not until 2006 that the final volume of the now enormously expanded, 14-volume, second edition was published. It was just in time to begin plotting the third.

The EI3, says project manager Maurits H. van den Boogert, is likely to take some 15 years. This next edition, he says, “has explicitly incorporated the multitude of academic approaches and has a wider view on Muslims across the globe.” It is also, he adds, “less Arab- and Arabic-centered,” with both Persian and Turkic specialists on its board, and a far greater number of Muslim writers and others from non-European backgrounds.

Physically, it was in 1961 that Brill’s ever-growing collection of set-in-lead typefaces prompted it to move the printing plant to the outskirts of Leiden, to Plantijnstraat, aptly named after the 16th-century printer Christoffel Plantijn. The editorial side of the business followed in 1985, and soon the digital printing revolution led to the scrapping of literally tons of lead fonts. Despite a few modern business setbacks—a misguided acquisition and threats of a hostile takeover—Jordan Luchtmans’s 18th-century marketing strategy remains sound. It’s as plain as the entranceway to the company’s Plantijnstraat headquarters, which features not the Brill colophon, but rather a colorful, checkerboard pattern of some of the company’s most arcane letters and punctuation marks, many of which are familiar to only a handful of scholars on the planet.

“Partly, it has to do with tradition,” says van den Boogert. “Arabic, Hebrew, Aramaic, Japanese, Chinese: From the start, Brill had a tradition of handling such complex scripts.” In his view, it is the company’s commitment to this tradition that has helped it survive.

“Other publishers have moved out of such publications, which has only strengthened Brill’s position as a specialist in these kinds of things. So people come to us, and they say, ‘We have a text which is Old Mongolian; would you be able to publish it?’ and we can. So this is part of Brill’s identity,” says van den Boogert.

Digital books are the latest challenge, says publishing director Joed Elich, who oversees Brill’s Middle East, Islamic, African, and Asian Studies departments. “If we make an e-book, we have to make 20 different versions, for the Kindle, for Sony, for all of these different browsers, not all of which support certain characters. It’s complicated.”

Nevertheless Brill today publishes some 600 titles a year, together with 200 periodical journals, all of which are also available online. Disciplines have mushroomed, now including African studies and Asian studies; art and architecture; human rights; humanitarian and international law; social sciences; slavic and Eurasian studies; as well as traditional fields such as philosophy and religion. Arabic studies remain central, but have much company: Brill’s Middle East and Islamic studies department accounts for about one in six of the firm’s titles annually, and only one-eighth of the journals. In addition to the full texts of EI1, EI2 and the ongoing EI3, Brill also makes available online the Index Islamicus, a century-old, bibliographic database of publications in virtually all areas of Islamic studies, which it maintains through a team of bibliographers from London’s School of African and Oriental Studies and a satellite office in Madrid.

Today, Brill’s second building, overlooking the Oude Rijn Canal, left, is full of apartments. In 1961, unable to accommodate its growing publishing business and the growing collections of multilingual, lead typefaces that it required, Brill moved to the outskirts of Leiden, above; the lead type was discarded in the 1980s with the digital revolution. Today, the address on Plantijnstraat—aptly named after the 16th-century printer Christoffel Plantijn—remains Brill’s head office.

With around 100 employees in Leiden and 20 more working mostly in sales in Boston, Brill remains small compared to its main competitors in today’s academic publishing field, such as the uk’s Routledge or the university presses of Oxford, Cambridge, Chicago, Yale or Harvard. But neither Elich nor van den Boogert is especially troubled.

“Our books have always been for niche, small audiences, not the mass market of conglomerate publishers,” says Elich. The company’s customer base is, in fact, largely institutional: academic libraries and universities that can afford to pay the comparatively high prices for Brill titles, in both their print and electronic versions. (For example, the online edition of the EI3, which includes EI1 and EI2, costs $31,730.) This does not mean, as van den Boogert is quick to add, that Brill publications—especially in electronic formats—cannot serve a wider reading public.

“These texts are used in the classroom because their Arabic is relatively easy to read, in the sense that students can easily grasp their meaning, specifically with the historical texts,” says van den Boogert. “Now, if you only have the 1876 edition of such a text, in one copy in the library, which you can’t really open because it’s been bound too tightly, then you can’t really use it in the classroom. But when it is online, it’s open to multiple users and new possibilities, particularly when paired with an English translation.”

In the Arab world itself, too, the firm’s reputation has steadily grown. “More and more scholars from the Islamic world—from Egypt, from Lebanon, Tunisia, Malaysia—are publishing with us. We are also trying to translate more of our books into Arabic as well,” says Elich. In 2012, Brill won the Abu Dhabi Book Festival’s annual Sheikh Zayed Book Award for publishing and distribution excellence in Middle East and Islamic Studies—a badge of recognition from a leading hub of the fast-growing Arab book and publishing world.

The path to Leiden and Brill that once bore the footprints and inkblots of centuries of scholars is now traversed largely from one screen to another over data networks. Today, Amin ibn Hasan al-Halawani al-Madani al-Hanafi might have never bothered to sell his collection at all: Brill might have helped him find a web hosting agreement with Leiden’s library. But both before him and after, Brill’s books bridged centuries, continents and a polyglot world to introduce Western and now world readers to countless literary treasures of the Arab and Islamic worlds, and more. In our age when book publishing is struggling to come to terms with its future, Brill’s hold on its founding mission seems as rare—and as precious—as the very titles it stamps with its 332-year-old colophon.

You may also be interested in...

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

Cartier and Islamic Design’s Enduring Influence

Arts

For generations Cartier looked to the patterns, colors and shapes of the Islamic world to create striking jewelry.

Nasreen ki Haveli: Pakistani Textile Museum Fulfills a Dream

Arts

Collector Nasreen Askari and her husband, Hasan, have turned their home into Pakistan’s first textile museum.