A Crude History

In the oblique and often provocative ways of contemporary art, the 17-artist exhibition “Crude” probes the roles of oil in cultures and societies of the Middle East through the eyes of artists of the region. It is “art rooted in the Gulf, yet addressing universal ideas,” says Antonia Carver, director of the new Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai, which in November inaugurated its galleries with the show.

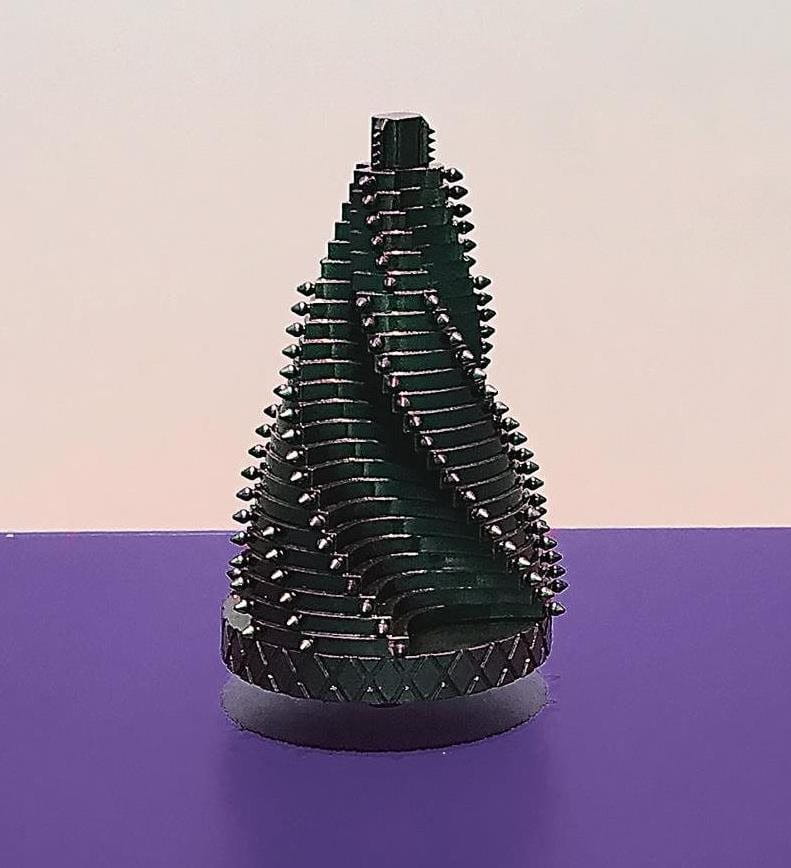

An iridescent green cone appears to levitate a few centimeters above its royal purple background like a fairytale wizard’s hat. But this is a replica of a shark-toothed head of a drill capable of spinning through rock as the literal cutting edge in the extraction of oil from the earth. Its sensually shimmering color comes from thick coats of automobile paint. A mundane industrial tool reimagined as a talisman of miracles—even magic.

“There are surprisingly few art exhibits dedicated to oil,” says curator Murtaza Vali, 44, who works both in New York and Dubai. “As the environmental and ecological concerns of oil use have grown, they have become the focus of attention among Western artists. But as I looked at artists from the Middle East,” he continues, “I found work that was looking not only at oil’s impact in the present and the future, but also at its history, its past.”

Vali spent nearly five years assembling works of paper, sculpture, video, found objects and installations from 17 artists and art collectives—all but one of them from Middle East backgrounds. As Vali guides me through “Crude,” I realize that the histories these works narrate are deeply complex and multileveled. Together, Vali explains, they engage aspects of prosperity and upheaval, economic development and conflict—all facets of what has become the world’s most vital commodity.

As I looked at artists from the Middle East, I found work that was looking not only at oil’s impact in the present and future, but also its history, its past.

—Murtaza Vali

One of the most personal pieces is a video installation, “If I Forget You, Don’t Forget Me,” by Manal AlDowayan, who used oral histories and personal artifacts to focus on individual lives transformed by the opportunities that came with the oil industry in Saudi Arabia. Although it documents an economic transformation from poverty to wealth, a sense of loss nonetheless suffuses these testimonies, even when they are celebratory. The industry has elevated many people materially, but it has also brought challenging social changes to traditional family structures. Wealth, she seems to say, has come with a price tag.

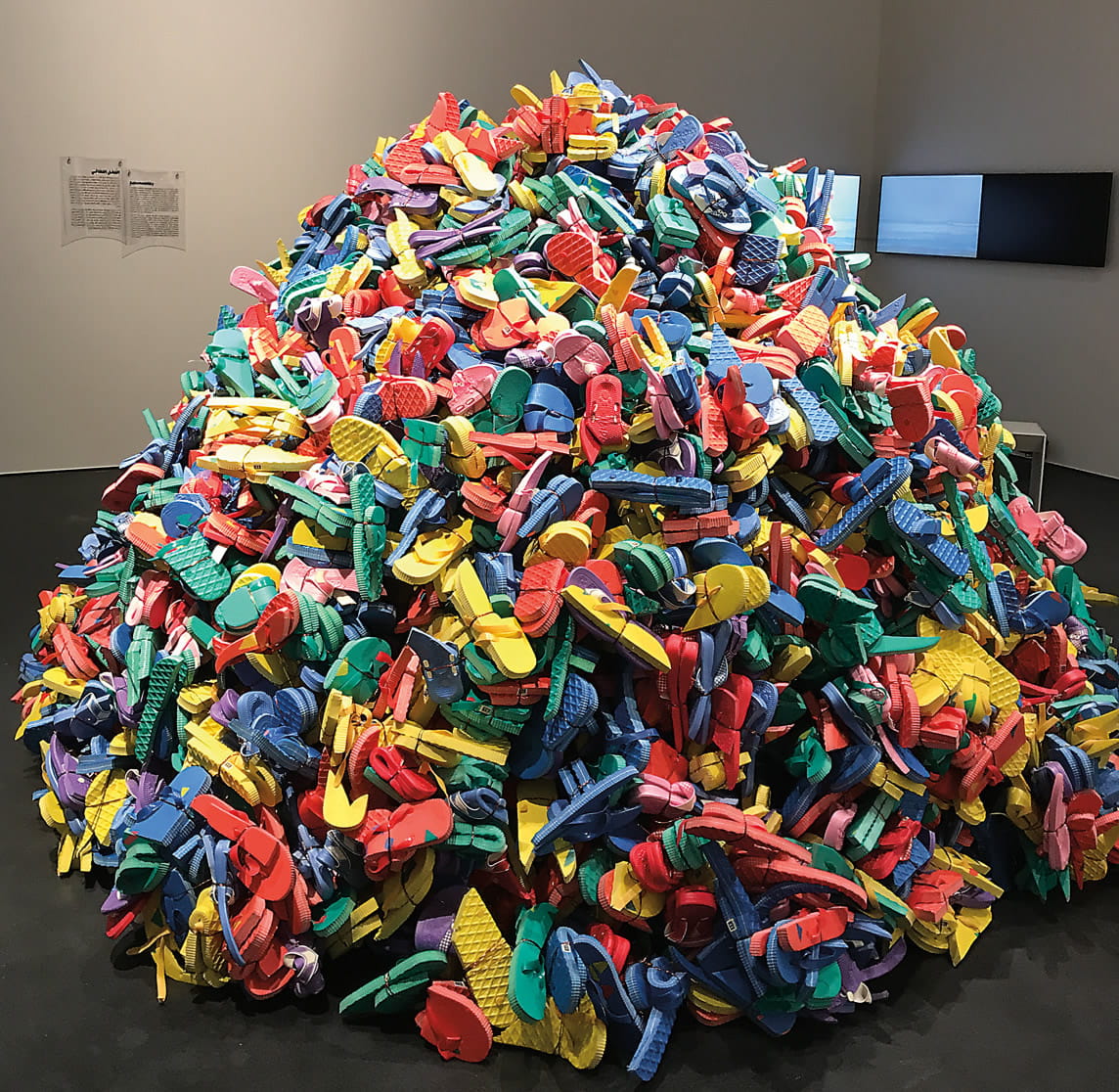

Others such as Hassan Sharif point out that while oil has given the modern world everything from lipstick to jet fuel, it also, along the way, has given us plastic footwear. His dramatic pile of garishly colored, cheap sandals (“Slippers and Wire”) confronts the viewer with, as Vali puts it, “a critique of the rapid consumerism that happens in Gulf societies as they go from a subsistence economy to an economy of abundance.” The act of piling them in the gallery, Vali says, “reduces a functional item to its materiality, to a mass of plastic or synthetic rubber”—oil metamorphosed into the mundane.

“The artworks are a way of telling history without having it be boring,” Vali says as we consider Sharif’s sandals. “Art shows you history without being didactic. Artists are like history buffs, super-enthusiastic about one odd episode.”

To Jameel Arts Centre Director Antonia Carver, who formerly oversaw the annual Art Dubai fair, this is what made “Crude” a strong debut. “We want to showcase art rooted in the Gulf, yet addressing universal ideas,” she says. “There have been virtually no exhibitions on this theme. That made the choice of subject matter even more relevant and urgent.”

Raja’a Khalid takes a playful, even absurdist, approach to the relationships between oil-producing lands and oil-hungry nations. “Fortune/Golf” frames a 1976 cover of Fortune magazine that shows two American men golfing on a fairway of sand. Oil flares flame dramatically in the background; smoke billows, and the men, unperturbed, wear only white shorts and golf shoes. The startling image begs the question, “What kind of men have come to work in this desert landscape, who are so hungry for home they will burn under its sun?”

After the galleries, in the Art Jameel Shop, Vali points out Alessandro Balteo-Yazbeck’s “Last Oil Barrel.” At 3.5 centimeters tall, it’s a quite miniature wooden oil barrel, painted black. Alongside it sits a display that shows, in real time, the market price of a barrel of the real stuff. “The financial industry is one important technology that oil has produced and enabled,” says Vali. “That realization makes clear that the value of oil is not absolute. It is a part of the social relationship. This financial system, it’s an abstraction that we create amongst ourselves.”

The history of oil refracted in “Crude” is, Vali notes, “not authoritative, it’s not linear, and it’s not continuous or smooth. It is inherently a crude history.” From the magical and talismanic to the ironic and skeptical, it’s not unlike the wider world’s view of this era-defining commodity.

You may also be interested in...

Handmade, Ever Relevant: Ithra Show Honors Timeless Craftsmanship

Arts

“In Praise of the Artisan,” an exhibition at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, aims to showcase Islamic arts-and-crafts heritage and inspire the next generation to keep traditions alive.

How Gulf's New Museums Are Championing Cultural Memory and Heritage

Arts

The result of decades of planning, new facilities in Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arabian Gulf reflect the region's cultural renaissance and effort to preserve its heritage.

Orion Through a 3D-Printed Telescope

Arts

With his homemade telescope, Astrophotographer Zubuyer Kaolin brings the Orion Nebula close to home.