The Guide Who Led Briton Wilfred Thesiger Through Arab Marshes

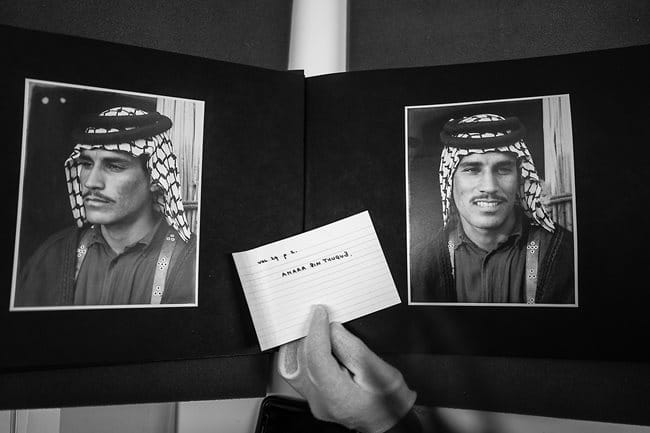

Amara bin Thuqub was a teenager in 1952 when he guided British explorer Wilfred Thesiger through the marshes of southern Iraq. Now 91, he is full of memories.

15 min

Written by Leon McCarron and Mohammed Al Sarai Photographed by Emily Garthwaite

On the afternoon that was to change his life, in the spring of 1952, Amara bin Thuqub recalls sitting cross-legged by the fire outside the reed house he shared with his family in the village of Rufaiya. His friend Sabaiti sat with him, and they sipped thick, rust-colored tea sweetened by plump, glutinous dates.

Both in their late teens, they shared news overheard from the older men, and in their actions and words, they tried to mimic their role models. One day, they themselves would be heads of households, and they discussed who seemed to lead bravely and wisely, and who didn’t. Every day usually followed the same routine, so when the village’s mukhtar, or mayor, arrived by their fire, it came as a surprise. He told the pair Falih bin Majid, the son of the shaykh, had requested their help. They were to prepare a boat for an important visitor, no time to waste. Both young men sensed an opportunity to impress.

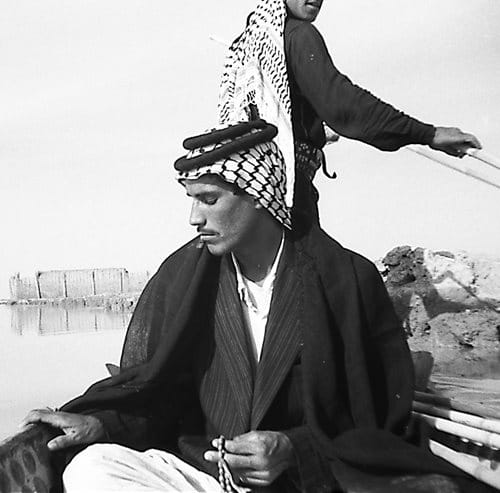

The boat was a thin, canoe-like tarada, 9 meters long with a sweeping, tapered stem at the front and pronged with decorative nails along the ribs. The boys laid a carpet suitable for a guest on the flat bottom. They then stowed a woolen bag, a locked iron box and a shotgun in the stern. Bin Thuqub remembers the guest appearing, his traditional gray dishdasha (robe) of southern Iraq and matching jacket hanging loosely from his broad, straight shoulders; his freshly shaven chin propping up his handsome face that showed his 40 years in fissures and creases as deep as those of the mountains and dunes in which he had spent much of his life. His name is Wilfred Thesiger, Bin Thuqub recalls being told, and he is from England. Bin Thuqub and Sabaiti were to help him with whatever he needed until his curiosity was satisfied.

“My first impression was that he spoke Arabic just like us,” Bin Thuqub recalls. “He was eating like us. There were no impressions he was like a stranger.”

Bin Thuqub imagined his assignment might last a day, perhaps two, but over the next seven years, the pair traveled frequently together, exploring the vast Mesopotamian marshes, during which time an unlikely and complex friendship was forged, one that was then severed as abruptly as it began.

In the spring of 1932, a young couple from Rufaiya went north from the central marshes to visit the town of Amara. Naga Muhsen was nearly due in her pregnancy, and when she went into labor in the town center, a local family rushed her into their home, where she gave birth on the kitchen floor. The kindness of these strangers, and the novelty of the location, prompted the couple’s choice of name for their first child: Amara.

They brought their son home to Rufaiya, where they lived with 150 other families, the majority of whom worked as farmers on land owned by Bin Majid. The extent of the Mesopotamian marshes, which gather in the vast floodplain around the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, was then around 20,000 square kilometers (today, the maximum extent is estimated at less than half that.) According to Mahdi al-Saadi, a journalist from Iraq’s southern governorate of Maysan, where the eastern marshes are located, “the first half of the 20th century was the golden age for the marshes in terms of the natural flow of its environmental cycle.” Blissfully absent, he says, were the issues of pollution, drought and climate change that now plague the wetlands.

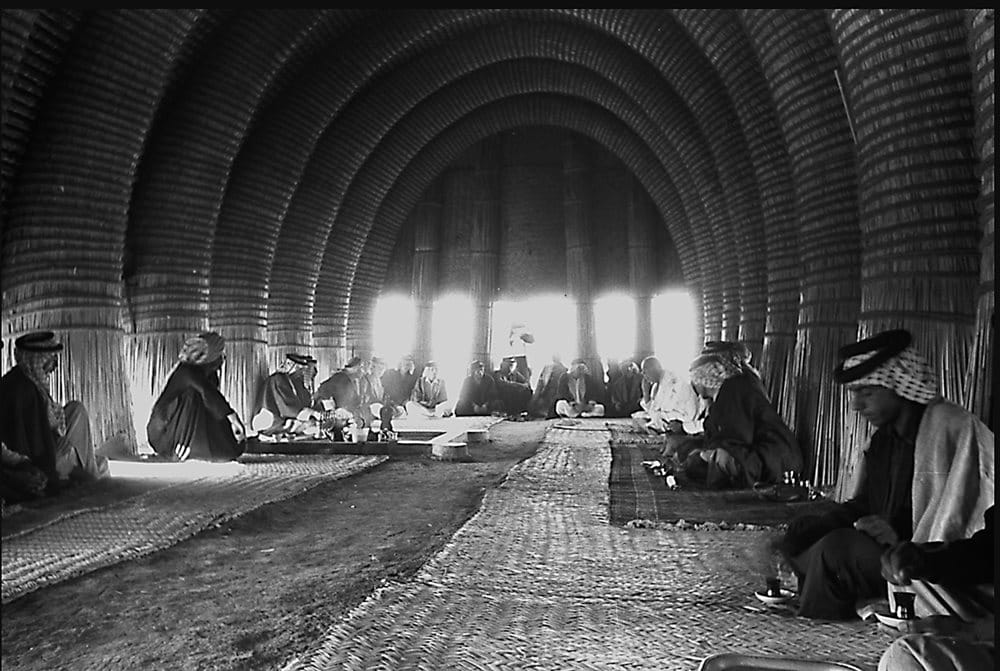

By the age of 12, Bin Thuqub had four brothers and four sisters. The family owned a small number of buffalo, which grazed on grass cut and collected by the women. Their home was made in the traditional way of the marshes, with intricately bound reeds gathered from the beds that surrounded them, arched into an opening at one end that looked out on a similar but more rudimentary shelter for the animals.

The ecosystem of the marshes might have been thriving, but for families like Bin Thuqub’s, life was far from easy. “People were indirectly enslaved by the feudal shaykhs,” says Iraqi historian and author Jabir al-Juaibrawi. The shaykhs leased the marshland from the nascent government of Iraq, which had gained independence from a British mandate in 1932 but, throughout the following two and a half decades, had found itself caught between lingering colonial influence and internal unrest. Though wars and sectarian conflicts have diminished the marshlands drastically since the 1950s, there remain areas where residents continue to live much as people have for more than 3,000 years, including Bin Thuqub and his generation: in mudhifs, the barrel-vaulted homes constructed of bundled reeds harvested from the marshes themselves. “An extraordinary architectural achievement with the simplest of materials,” wrote Thesiger. With little opportunity or inclination to leave, young men like Bin Thuqub dedicated themselves to crops and animals, and the years passed with the cyclical harvest seasons.

By the time Thesiger reached the Iraqi marshes, he had already spent two decades traveling among communities of whom little was known in the West. Born in Addis Ababa, in what was then Abyssinia, now Ethiopia, he was educated at Eton and Oxford. He returned to Abyssinia at age 23, to lead an expedition in the Danakil Desert, one of the hottest places in the world. He fought with British forces in Sudan and Syria. He twice crossed the Rub’ al-Khali (Empty Quarter) of the Arabian Peninsula led by Bedouin guides, journeys he wrote about in his 1959 book, Arabian Sands, which remains a classic of adventure literature. “Like many English travellers I find it difficult to live for long periods with my own kind,” he wrote in a collection of his work called Desert, Marsh and Mountain. He liked to box in England and shoot big game in Africa and, as he got older, so too did his atavism increase. Ahmed Saleh, a researcher from Maysan and a tourism pioneer in the marshes, believes Thesiger saw “the atrocities modernity committed in his homeland,” England, and sought out places unspoiled, to his mind, by greed and reckless development.

Thesiger’s friend and biographer Alexander Maitland wrote that Thesiger “took an aggressive pride in being the ‘last’ in a long line of overland explorers and travellers, a refugee from the Victorians’ Golden Age.” Thesiger, he wrote, envied the freedom to roam in remote places seemingly untouched by industrial culture, as exemplified in the 19th century by Charles Doughty’s Travels in Arabia Deserta and, a generation later, by the exploits of T. E. Lawrence. By the 1950s the marshes of southern Iraq were some of the few places in which the waning British Empire still had influence yet in which Thesiger’s nationality would not count against him.

In Iraq, as elsewhere before, Thesiger sought local companions as guides, often young men or boys, as they tended to be freer to travel for weeks or months than their elders. This is how he came to meet Bin Thuqub and Sabaiti, as well as two others, Hasan and Yasin. In his 1964 book, The Marsh Arabs, Thesiger declares that “Of my four regular companions, Amara and Sabaiti were my favourites, and, away from their fellow tribesmen and the familiar setting of the Marshes, the three of us were drawn still closer together on these expeditions.” He tells of the crew’s adventures together, touring village to village by boat, hunting wild boar and slowly peeling back the layers of life in the marshes.

With time, Thesiger became more involved in the affairs of Bin Thuqub and his family. As Bin Thuqub describes it, “He took care of me like a son. He was more than a friend and brother.”

Thesiger visited the marshes each year, usually from late winter until summer, between 1951 and 1958, with only one exception in 1957, sometimes staying as long as seven months. While the book is regarded as another classic of travel literature and—in the best sense of the term—amateur anthropology, it is, like Thesiger himself, a paradox: It can be read as both the indulgences of a wealthy orientalist whose value system was largely outdated even then, and as an astute, sympathetic documentation of a remote and uniquely adapted community. In it, he betrays his own desperate longing to belong. Saleh calls Thesiger “the good colonial,” for his focus on celebrating the marshes and its oft-marginalized people, giving voice to men like Bin Thuqub.

“The bond between us was like father and son. He was more than a friend and brother.”

—Amara bin Thuqub

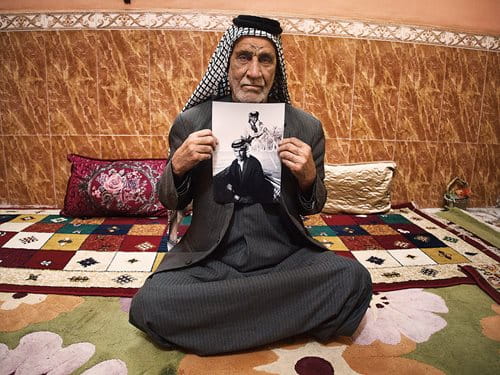

Bin Thuqub is now 91. His family and friends mostly call him Abu Hamid to honor his age and first son, but he still likes the name Amara, because it reminds him of the adventures of his youth. He lives with his wife, Khashiyeh Shamekh Nikhash, daughter Amal, and granddaughter Rusul in a small, two-story house behind a high wall in al-Shu’ala, a modest district at the northeast edge of Baghdad, where urban sprawl melds with wheat fields beyond. It’s a noisy and busy neighborhood, with wrinkled streets filled with three-wheeled yellow tuk-tuk taxis and small-goods trucks belching exhaust. Tattered political posters adorn rough cement walls.

Bin Thuqub sees little of this disorder, and cares less. He sits mostly in his majlis, or guestroom, 8 by 5 meters, with peach walls. One poster, one clock and one framed picture of himself are the only decorations. A multicolored floral carpet covers the whole floor. Along the sides lie a second layer of rugs, adding to the kaleidoscope, with cushions placed not too far apart. It’s not hard to imagine its similarity to the earthy interior of a traditional mudhif. Mostly these days, Bin Thuqub says, “we don’t move a lot from here. We just go for weddings, and funerals. We go to see our relatives.” When they do, they are likely to hear of his adventures as a young man.

He is still tall and slim, and he speaks with a raconteur’s finesse still reminiscent of the young man Thesiger described as “slightly built and remarkably handsome,” and “deft and self-possessed, a natural aristocrat.”

He wears a dishdasha and jacket, and a black-and-white shumagh (headscarf) frames the furrowed impression of devotion on his forehead. The chance encounter with Thesiger afforded him an opportunity to travel, he says, and to become respected throughout the central marshes. “They were the best days of my life,” he maintains. “I consider them beautiful.”

Bin Thuqub has a keen memory for detail and numbers. He can tell you the cost of everything throughout his life, from the 40 dinars in annual rent Sabaiti’s father paid Shaykh bin Majid to lease a space for a village shop to the price of every house he has ever lived in since leaving the marshes (400 dinars to buy his first house in al-Shu‘ala in 1977; 28,000 dinars when he sold it in 1992.)

Thesiger entrusted Bin Thuqub to manage his accounts, and it was through this bond of trust, Bin Thuqub explains, that real friendship developed. “He had an iron case full of money,” says Bin Thuqub. “And he gave me the keys. When he checked the accounts and found not a single dinar was missing, he told me, ‘you are honest and trustworthy.’” For Bin Thuqub, this was the greatest compliment. Thesiger had validated Bin Thuqub’s own belief in himself as a natural leader. “I didn’t change around him or anyone else. I was the same, and Thesiger considered me as a precious friend. He was a good influence.”

A recurring theme in The Marsh Arabs is Thesiger’s self-taught, peripatetic doctoring. He almost seems to revel in the grisly details of sores and boils and amputations, and even the removal of an eyeball. His specialty became male circumcision, an important and obligatory ritual in the religious traditions of the marshes. Prior to his arrival, the procedure was carried out by wandering surgeons who would often operate with a piece of string, a rusty razor and no antiseptics. Thesiger, with his sterilized scalpel, anesthetic and penicillin, soon became the favored option. Maitland, who noted that before arriving in Iraq, Thesiger had never performed a circumcision, deduced from Thesiger’s diaries that he likely carried out well over 6,000 procedures in the marshes.

Bin Thuqub became Thesiger’s medical assistant. “I liked the work of doctoring. I helped Thesiger to give injections, and I learned to help,” he says. Often the pair would spend entire days working under the sun, moving from circumcisions to injuries, infirmities and all manner of ailments as families congregated around them in village after village. In his reminiscences, Bin Thuqub doesn’t dwell on blood or drama, but instead the enjoyment of the skill. “I liked learning,” he says. “It was so useful. Even when the work was hard, it was rewarding.” Today, he still administers injections to family members when needed.

By 1956 Bin Thuqub had arranged to marry Baheyah, the sister of his friend Sabaiti. Thesiger, Bin Thuqub says, “was like a father at this time” and even helped pay the bride price of 60 dinars.

The engagement was followed by a quick wedding, and Bin Thuqub began excitedly to prepare for family life. But in the early summer of 1957, his father died, and a heartbroken Bin Thuqub took his body to the cemetery in the city of Najaf. Two weeks later Baheyah also died, minutes after giving birth to their first child. For the second time in a month, Bin Thuqub made the journey to Najaf. “It was a miserable time in my life,” he says, and he still blinks away tears in the recounting.

In 1958 Thesiger left in early summer as usual, telling Bin Thuqub that he’d be back the following spring. It was the last time they ever saw one another. That July Bin Thuqub joined a crowd of tribesmen in Bin Majid’s long, thatched mudhif to listen to the news on a small radio. Iraq’s King Faisal II had been executed, they heard, along with Prime Minister Nuri al-Said. The revolution was driven, in no small part, by a desire to expel the influence of the British who had propped up the Baghdad-based monarchy. From that moment, says Bin Thuqub, “I suspected that I might never be able to see Thesiger again.” But still, he adds, “I didn’t think it would be forever.”

A few months after this, police arrived at the mudhif asking to identify anyone with connections to the Englishman. They were sent away, but the following year, Bin Thuqub made a rare trip to the town of his birth, and there an informer identified him. “They took me to jail for 15 days and asked about [Thesiger] every day. I told them nothing.” Eventually a judge threw out the case, and he was released. He smiles thinly when he thinks of it. “It was a strange time,” he concludes, but for the next two decades, he avoided leaving the marshes except when absolutely necessary.

Later in 1958, after the revolution, Bin Thuqub remarried, to Nikhash, whom he had met during a visit to her village with Thesiger in their medical capacity. “I was bringing them food and water,” remembers Nikhash. “When Amara set his eyes on me, I knew he wanted me. I was so young then, but I wanted him too.” She thinks she was probably about 16, and within a year of marriage, she gave birth to a daughter. Three more girls and two boys followed.

The revolution swept out not only British influence but also that of the shaykhs who had controlled the rich farmlands in the marshes. For the first time in his life, Bin Thuqub was a landowner, “alone and working hard,” but “it felt good to own it.” He and Nikhash settled into a new rhythm of life in Rufaiya, but it was still a demanding existence. Profits were low and the toll on the body high. Bin Thuqub’s siblings, like many thousands of other Marsh Arabs, drifted to the cities in hopes of making a better life. In 1973 the British writer Gavin Young, who had first visited the marshes with Thesiger, returned to Rufaiya to find Bin Thuqub. For a few days, they traveled together as they had done 16 years earlier, but it was to be a last free-roaming adventure for them both.

In April 1977 Bin Thuqub moved to al-Shu‘ala. He sold all his water buffalo as well as the rifle Thesiger had given him, and the proceeds therefrom afforded him enough to buy a small house. Since that time, he has never returned to his land in Rufaiya, though he still keeps the faded deed for 7 dunams, or 7,000 square meters. Today the paper is worthless, as the legal system prohibits ownership of unused land, but its value is not countable in dinars: It is his last tangible connection to the only place he ever really belonged.

In al-Shu‘ala Bin Thuqub worked for 11 years as a storekeeper in a hospital, then five as a private guard outside a debt store. At the hospital, he says, “They asked me not to wear my traditional clothes, but I refused, and I left. They eventually brought me back and said I could wear what I wanted.” For the rest of his working life, he insisted on wearing his clothing from the marshes. Nikhash worked, too, serving tea at a road transportation office. In 1988, they sold their house and followed Bin Thuqub’s brother to al-Hasla, close to the town of Abu Ghraib. There Bin Thuqub worked the potato harvest, with some carpentry on the side. They made decent money and bought a bigger house. In 2006, however, the sectarian fighting in the area became too dangerous to tolerate, and the couple returned to al-Shu‘ala.

Yet the violence of war was at times inescapable. During the Iran-Iraq War, one of his sons was imprisoned for trying to escape military service. He died in jail at age 17. Bin Thuqub’s youngest son, Hadi, became a soldier and, in 2016 in Falluja, was shot in the head by an ISIS sniper. A friend rushed him to an operating room. Before the surgery, Bin Thuqub had to sign a waiver absolving the state of fault if Hadi died. But he recovered fully and today lives a 10-minute walk from his parents, and he often brings his five children to visit them. “I prayed every day,” Bin Thuqub recalls. “Thank God he is okay. The doctors didn’t believe he could make it.”

“We have 11 grandchildren. Thanks be to God,” says Nikhash. She is 80 now, and she wears a velour abaya with small blue printed flowers. Her skin is loose and gathered in folds, her wrists almost as thin as pencils. She laughs easily. They’ve adapted to city life, she says. But no, it is not the same.

“I regret leaving,” says Bin Thuqub. It is the only regret he ever expresses. “We don’t know where our food comes from now,” Nikhash adds, and it’s expensive. “In the marshes we had milk from the buffalo, eggs from the chickens and fish to catch. … Everything was there.” Despite the hardships, Bin Thuqub says, “our life there was precious.” But the land they left is no longer what remains. In the 1980s and 1990s, the marshes were devastated by war and drained of their waters by Saddam Hussein. Today a combination of weak governance, geopolitical tensions and climate change all risk rendering the marshes even more uninhabitable in the future.

Thesiger’s writing is one kind of the recent past’s essential records. But the living, oral memories of Bin Thuqub and Nikhash are no less valuable, if much less celebrated. Basra-based novelist and heritage expert Nawal Juayid points to elements of endangered heritage of which they and others from that era in the marshes are custodians. “The first is the intangible verbal heritage, and that includes the literary dialect that Marsh Arabs used to be known for,” she says, noting the poetry and stories of the shaykhs, elders and farmers that enshrined a way of life and passed from one generation to the next. “All of that began to disappear gradually since the days of Amara and Thesiger,” says Juayid. Then there are “the many forms of tangible visual heritage,” like traditional architecture and clothing. “These elements comprise the ideals of a homeland,” she concludes. “Once they’re lost, the homeland is lost too, regardless of the amounts of water pumped into the marshes.”

Bin Thuqub and Thesiger had a complex, unequal friendship, one that marked both their lives. Thesiger’s memories and knowledge live on in print, given voice by his capacity to write and publish. Amara’s memories and knowledge live on, for now, in a suburb of Baghdad where grandchildren hear his stories, including those of his adventures in a 9-meter tarada with an Englishman. “I think of them often,” he says of those years. “And I thank God every day for the memories.”

About the Author

Emily Garthwaite

Emily Garthwaite is an Iraq-based photojournalist, Leica Ambassador and storyteller focusing on environmental and humanitarian stories.

Leon McCarron

Leon McCarron is a writer and broadcaster living in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. He is the author of two books and and a forthcoming third, Wounded Tigris: A River Journey Through the Cradle of Civilisation (Corsair, 2022).

Mohammed Al Sarai

Mohammed Al Sarai is an Iraqi journalist working on investigative reports and on stories related to Iraqi heritage.

You may also be interested in...

“Old Bridge” Story Inspires Lessons in Writing and Community History

History

Pearls, Power and Prestige: The Symbolism Behind Byzantine Jewelry

Arts

History

A 1,500-year-old gem-encrusted Byzantine bracelet reveals more than just its own history; it symbolizes an empire’s narrative..jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5&cw=480&ch=360)

Photo Captures Kuwaiti Port Market in the 1990s

History

Arts

After the war in 1991, Kuwait faced a demand for consumer goods. In response, a popular market sprang up, selling merchandise transported by traditional wooden ships. Eager to replace household items that had been looted, people flocked to the new market and found everything from flowerpots, kitchen items and electronics to furniture, dry goods and fresh produce.