Nass El Ghiwane: Folk Musicians That Changed Morocco

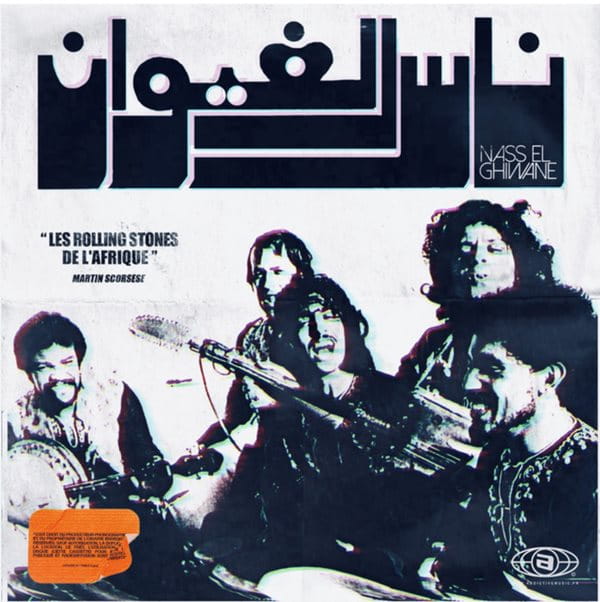

This group of five young folk musicians became the voice of Morocco in the 1960s and beyond. Martin Scorsese called them “the Rolling Stones of North Africa,” but to Moroccans they were the sound of an entire generation in a charged moment of global pop culture.

Said Graiouid was a teenager living outside Casablanca in the early 1970s when he first heard the music of a newly formed ensemble, Nass El Ghiwane.

“They came out of nowhere,” recalls Graiouid, currently provost and dean of faculty at the School for International Training in Vermont. “It was literally an eruption. I remember very well one fine morning, out on the streets, we were all humming the lyrics of this band that we had heard the night before on Moroccan television.” The lyrics were simple evocations of daily life, a kind of affirmation of what it meant to be a Moroccan.

Nass El Ghiwane featured five young folk musicians of diverse ethnic and geographic backgrounds playing various instruments—the guembri bass lute, traditional drums and a banjo. They sang in local languages, notably Amazigh, the language of the Moroccan Berbers. They wove stories and proverbs into their own compositions, unlike the familiar semi-classical repertoire Moroccans knew well, such as Andalusian al-ala and Arabic tarab.

“the Rolling Stones of North Africa”

— Martin Scorsese

Western music critics and film director Martin Scorsese described the band as “the Rolling Stones of North Africa,” appropriate because Nass El Ghiwane brought together an entire generation of North Africans in a charged moment of global pop culture. The group’s music has had even more specific relevance for Moroccans: It helped establish a post-colonial national identity after the country’s independence from France.

When it came to music, most of what Moroccans heard came from the East, in particular Egypt, with its venerable tarab style, where a single lead singer fronts an orchestra and sings romantic poetry. Young Moroccans also heard the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix and, yes, the Rolling Stones. But this new, local sound—a fusion of folk, trance, traditional and other styles—resonated more profoundly.

Nass El Ghiwane awakened a pride heretofore unknown in Morocco, and it did so by drawing on previously marginalized musical styles, such as Gnawa, a ritual music performed in healing ceremonies by descendants of enslaved people brought from sub-Saharan Africa centuries before.

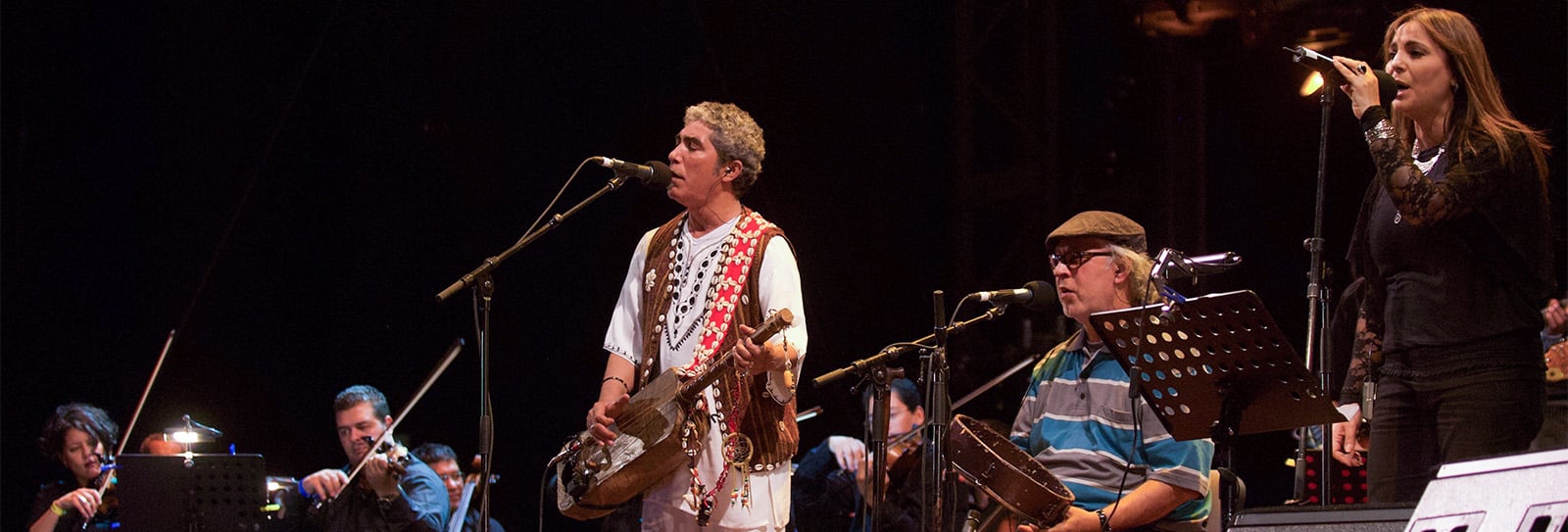

Nass El Ghiwane performs at the Mawazine Festival in Marrakesh, Morocco, in 2011.

Graiouid and many other young Moroccans found the music clarifying. “We were all wondering about which way to go: East or West? To modernize or not to modernize and how to modernize within the pan-Arab ideological framework. All of a sudden, this band was able to come up with poetry that was neither Eastern nor Western, a poetry rooted in the culture and the context of the country.”

Graiouid says Nass El Ghiwane effectively decolonized Moroccan music.

The musicians met in Casablanca as members of an experimental theater group. They came from both rural and urban backgrounds.

Omar Sayed, who led the group after the original leader, Boujemaa Hagour, was killed in a car crash in 1974, was versed in Amazigh music. Abderrahman Paco of Essaouira joined early on playing guembri, bringing the Gnawa trance element to the fore. Compositions echoed songs their rural mothers used to sing, sometimes turning them into solo vocal introductions. Amazigh, Gnawa, Sufi and Andalusian elements coalesced in a sonic template for an emerging nation.

“Nass El Ghiwane were oriented towards the future while being very respectful of, and very affectionate about, what they regarded as the past,” American University ethnomusicologist Kendra Salois says.

History of diversity

Nass El Ghiwane released Le Meilleur in 2018.

Present-day Morocco is positioned at the crossroads of cultures and empires, according to the Moroccan National Tourism Office. It was first inhabited by the Amazigh and later colonized by Phoenicians and the Romans.

Arabs brought Islam to the region in the seventh and eighth centuries and, as noted in Britannica, Morocco became the launching point for Arab incursion into Europe, leading to the centuries of Al-Andalus, medieval Moorish Spain. Following the Spanish Inquisition’s Alhambra Decree in 1492, Muslim and Jewish Andalusians flooded back into Morocco, bringing with them a unique hybrid culture that further diversified the country’s population of Arabs, Amazigh tribes and sub-Saharan African descendants.

The official website for the Kingdom of Morocco says it was so named by 19th-century cartographers, later becoming a French protectorate lasting from 1912-1956, when the sultan became king of an independent Morocco. Whereas Rabat, Fes, Tangier, Meknes and Essaouira had long, rich histories, Casablanca’s went back only to the 18th century.

Casablanca grew rapidly during the French era, but its new residents came from elsewhere, bringing with them ties to the rural traditions and cultures of their ancestors. The members of Nass El Ghiwane were first- or second-generation residents of Casablanca, whose demographics were unlike that of any other city in Morocco.

“These are all part of what [Casablancans] grew up with,” says Salois. “To my understanding, despite the collective effervescence over independence, you were less likely to identify yourself as a Casablancan. You were more likely to identify yourself as ‘I'm from this group of people; I just live in Casablanca.’”

Graiouid describes the identity crisis Moroccans experienced after independence. “There was the colonial experience, and now the colonizer has gone. But you're left with this psychological fracture. You’re not sure who you are… Very serious political decisions were made on the basis of which direction to go.”

Among those was the decision enshrined in the 1962 constitution that Arabic would be the country’s official language. Graiouid says at least 50% of the population then, and still today, speak Amazigh.

Nass El Ghiwane enabled Moroccans to reconcile with their own culture and heritage. They leapt beyond the colonial experience, according to Graiouid, to say, “‘This is who we are, and we should be proud of what we have, using it to create our own identity.’”

For the band, poetry, instruments, look, language and musical style all coalesced in songs that entranced Moroccans. Graiouid cites “Essiniya” as the song that cemented the band’s place in the collective consciousness. “’Essiniya’ is the tray that we use when we serve tea. Every single Moroccan home has a tray… It's a ritual. You have the everyday tray, and you have a tray for when there is a guest. It's a metaphor of community, of gathering, of being together.”

At the same time, the song has a distinct sadness about it, the quality of huzun. “Huzun is very close to melancholy,” says Graiouid, “but it's not melancholy. You're not experiencing huzun because you are sad and you want to get out of it. It is a state of feeling that one longs for and wants to be in because it is also a moment of connection, of creativity and inspiration.” Graiouid says that Boujemaa, who sang “Essiniya” in a searing, mournful cry, was “the voice of huzun.”

A young girl enjoys the concert.

A cultural archive

Nass El Ghiwane’s songs are not explicitly political, but the group’s approach gave it leeway. Salois says, “Because the language they used was old fashioned and because of their rhetorical strategies, they could say things that were generally interpreted to be critiques of corruption, or surveillance, and get away with it.”

One example is “El debbana fi-l btana,” a song about a flea living on a sheep’s hide. Many took this as a political statement, imagining that the flea wished to escape the confines of the sheep’s hide, but in an interview with Brown University literature professor Elias Muhanna, Sayed dismissed this notion. “That’s where it is supposed to live,” said Sayed. “However, when the sheep is alive, not dead. We were trying to say that this hide that the flea is living in was once a sheep. The hide remains, but the living thing is gone. We Moroccans, our generation, were living within the remains of something that no longer exists.”

Just the same, listeners are entitled to their own interpretations. The ambiguity is key. Graiouid notes that, from the start, Moroccan officials adopted an ambivalent attitude toward Nass El Ghiwane, occasionally pressing the group to drop certain songs from its setlist but also promoting the music on state radio and television. Like the griots of West Africa, the musicians enjoyed a certain license to speak truth to power, but within limits.

Graiouid’s current work posits music and culture as a kind of archive, a seat of collective memory, and Nass El Ghiwane is central to the narrative. “I think of them as Morocco's other archive that documents the memory of the country at a time when it was very difficult to write its history.”

Nass El Ghiwane sparked what Graiouid calls “a movement.” Many Moroccan bands—Jil Jilala, Tagada, Izenzaren, Lemchaheb—followed its lead, and Nass El Ghiwane has inspired followers throughout North Africa, including pioneers of Algeria’s räi music, another hugely influential genre. The band’s current musicians still live in Casablanca, and they still perform both locally and internationally.

Salois says Nass El Ghiwane’s songs are still sung at Moroccan weddings, admired by young and old alike. Sayed has referred to today’s generation of forward-looking hip-hop artists as “our children.” Few bands in the world can claim such a legacy.

You may also be interested in...

Tracing American Jazz's Roots to the Nile

Arts

The Nile river has been used as motif, a metaphor or both in popular culture, most prolifically in music in the United States for more than 125 years. The most notable uses of the Nile arose during the jazz period, which peaked in the second half of the 20th century and continues to this day.

Prince of Enchantment: The Oud

Arts

Often regarded as the forerunner and name- sake of the European lute, the ‘ud (oud), is among the world’s oldest continuously played string instruments. In Arab and other musical traditions, its deeply resonant, emotionally evocative tones earned it, over the centuries, the sobriquet amir al-tararb.

Rajasthani Folk Musicians Are Curators of Culture

Arts

Reaching out to new generations and global audiences, musicians in India's northwest state of Rajasthan draw on centuries of traditions that, to an untrained ear, may sound like Indian classical music. But what sets them apart are the regional stories they tell and the tone and power of the singers.