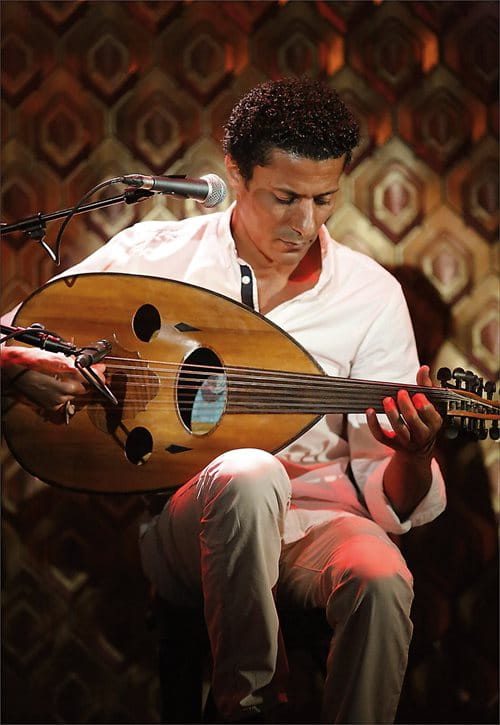

Lute and Lyres' Legacy: Echoes in The Oud Instrument and Beyond

For more than 4,000 years. people have adopted, adapted and adjusted the lute, resulting in its countless variations. Along the way. some innovations have proved both consequential and simple.

Arabian ‘uds and European violins; Chinese pipas, Indian veenas; Indonesian rebabs, West African koras and American electric guitars and banjos—all are descended from lutes, a family of instruments whose shared DNA includes strings that run parallel across a flat soundboard or belly up a distinct pole or neck. There have been countless variations of lute forms over more than 4,000 years as people across the globe adopted, adapted and adjusted instruments to satisfy a preference, meet a need or indulge a curiosity. What if I … added strings? Modified the shape? Made the neck shorter? Longer? On and on—and along the way, some innovations proved as consequential as they were simple.

For composer and musicologist Tarek Abdallah, whose research at France’s Université Lumière Lyon 2 has included a deep dive into the evolution of lutes into ‘uds. According to Abdallah, the first such innovation took place between the ninth and mid-11th centuries CE. At that time, the standard ‘ud had four strings, sometimes with an added lower fifth one. At some point, an anonymous luthier doubled each of the four standard strings. Now the instrument sported eight in pairs tuned to the same pitch with the optional ninth. This not only endowed the instrument with a fuller, richer sound, but it also turned out to be “an invention that revolutionizes everything,” says Abdallah.

For example, he says, ‘ud-makers had to widen the neck to accommodate the additional strings, and then they had to modify the head to fit four more tuning pegs. They also had to strengthen the instrument: When played, the vibrations of the strings travel through the bridge to the soundboard, temporarily pressing it in. The more strings, the greater the pressure and the more movement throughout the soundboard as it repeatedly presses down and releases.

The first known reference to doubled strings on ‘uds comes from the 11th-century-CE theoretician and musician al-Hasan ibn al-Musiqi al-Tahan, who discussed the effects of the doubling in his treatise, Hawi al-Funun wa-Salwat al-Mazhun (Encompasser of the Arts and Consoler of the Grief-Stricken). Abdallah explains that because of the stress and pressure double strings exert on the soundboard and bridge, Ibn al-Tahan recommended that a lute not be carved out of a single block of wood but be assembled from several pieces. Ibn al-Tahan further suggested that the soundboard be made of two or three pieces, thicker than the ribs of the soundbox and supported by an unspecified number of wooden bars.

This also made for a lighter instrument that was easier to handle, which Abdallah says he appreciates whenever he practices or performs with one of his own ‘uds.

Traveling back in time, the oldest surviving lute was made around 1490 BCE in Egypt, and it was buried alongside the musician Ḥvar-Moṡe. Carved out of a block of cedar, its body is a concave oval 43 centimeters long, 11.5 centimeters wide and 8 centimeters high. It is topped by rawhide that had been, according to a 1944 article in the New York Metropolitan Museum Art Bulletin, “stretched in place while still damp, eight short slits having previously been made in it and the neck passed through these; the hide shrank as it dried, so that it fitted the sound box tightly and clamped the neck down along the top.”

Yet it was itself a descendant from far older instruments. From paintings and texts, scholars know that lutes were one of the many cultural artifacts that were adopted in Egypt from Mesopotamia starting around 1550 BCE. Archaeomusicologists who specialize in the science of music and musical instruments can’t say how long people in Mesopotamia had been making and playing lutes. But they agree that it was sometime before 2330-2284 BCE when the carver of a cylinder seal depicted a scene filled with mythical and divine beings. Seated on the ground in their midst, a musician cradles a long-necked instrument with a round body, one hand picking or strumming and the other reaching around the back of the neck, fingers curled over the strings in front.

Richard Dumbrill, cofounder of the International Conference of Near Eastern Archaeomusicology, interprets that round body as a gourd, and over it, a stretched hide. “When you play it with your hands, it’s a drum,” he says. “Then you add a bridge and a neck, and it becomes a string instrument.” Dumbrill fetches his reconstruction of such an early lute which, in shape, resembles a modern-day banjo.

The drum, he says, becomes a soundbox, with the hide drumhead acting as a soundboard. As in Har-Mose’s lute, Dumbrill has slit the hide to create straps that, in this case, flank the center of the body. As in the cylinder seal carving, the neck extends beyond the soundbox to accommodate the length of the player’s forearm and then some.

At the head, Dumbrill has secured each string with rope that he has looped and knotted in a way that allows him to tighten or loosen tension on the string. At the lower end, he has tied the strings firmly to the tip. But had Dumbrill stopped there, the lute would be mute: The strings would merely hit the wood pole and the hide—thwack, thwack.

“When you play it with your hands, it’s a drum ... then you add a bridge and a neck, and it becomes a string instrument.”

—Richard Dumbrill

Enter the bridge.

Dumbrill points to the slim piece of wood that rises from the neck, near the center of the soundbox. It is firmly wedged and runs perpendicular to the strings, lifting them high enough above the soundboard to ensure that they vibrate unimpeded. But this is not all. On their own, strings cannot move much air, and the sound they produce is faint. Here, however, their vibrations travel through the bridge to the much larger surface of the soundboard, as well as to the sides and back of the soundbox. The effect of plucking those strings is now amplified as the air inside the soundbox comes alive with waves of sounds.

In this respect lutes are not alone. Ancient lyres also amplify notes thanks to a bridge and a soundbox. But where lutes and lyres differ is in the way musicians can adjust pitch, that is, produce different notes.

Lyres are U shaped with a crossbar at the top that spans the two arms and, at the base, a soundbox with a bridge. The strings run from the crossbar through open air to the bridge, which allows players to pluck and strum with both hands, one on each side of the set of strings. They tune every string to a pitch and, if they want more notes, they have to add strings.

On the lute, however, players can use each string to produce many pitches with the press of a finger. By pushing the string against the neck, they mark a new end point, thereby varying how much of the string is vibrating: The shorter the active length, the higher its frequency and pitch.

Lutes started out as “pastoral instruments,” says Dumbrill. And although “it is highly probable that if you were a peasant, you wouldn’t think in terms of rules,” the shifts in pitches and octaves that correlate to distinct notes would have guided practiced fingers from the earliest times.

Lutes started out as “pastoral instruments.”

—Richard Dumbrill

At Alaca Hüyük, an archeological center of Neolithic and Hittite culture in north-central Turkey, a relief produced between about 1250 and 1200 BCE depicts a musician playing a lute that shows marks on its neck—frets. This gave Dumbrill insight into the notes ancient musicians may have played. “From the moment you have the neck of the instrument and the bridge, and you have frets,” he says, “you can calculate hypothetically the value of the pitches.” Dumbrill later compared these to a similar study of Egyptian depictions from about the same period by musicologist Ricardo Eichmann. “We found exactly the same fret positions” relative to the length of their necks, says Dumbrill. The implications to him are clear: “So it means that from Egypt to central Turkey, and probably in the rest of the Babylonian empire and so forth, they had a standard system.”

In some cases, innovations have unwittingly retraced the steps of these same distant ancestors. Abdallah cites a well-known incident in 1957 when renowned musician Munir Bashir left Iraq to perform in Beirut only to have the bridge on his ‘ud snap and rip off part of the face. He set Muhammad Fadil, his luthier, the task of making him an ‘ud that would avoid such a fate. Fadil came up with a bridge that wasn’t anchored to the soundboard but simply rested on it, held in place by the strings—a floating bridge. It was ingenious, and “they presented it as an invention,” says Abdallah. “But as it turned out,” he cautions, “you can’t reinvent the wheel.” He points to Ḥvar-Moṡe’s lute: It too had a floating bridge.

The “huge step” occurred when someone millennia ago created the bridge itself, Abdallah says. Though musicologists like him and Dumbrill may never pinpoint who made that crucial tweak or when, it connects those early innovators to every descendant of their lutes and to the music they make, from village squares to concert halls to streaming playlists.

You may also be interested in...

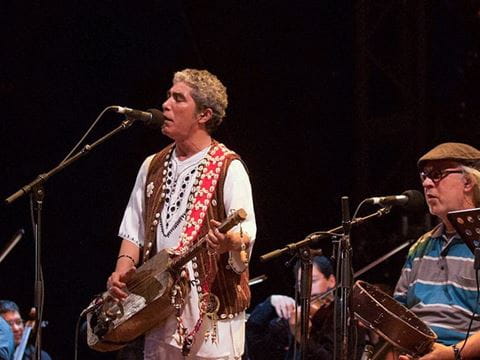

Nass El Ghiwane: Folk Musicians That Changed Morocco

Arts

This group of five young folk musicians became the voice of Morocco in the 1960s and beyond. Martin Scorsese called them “the Rolling Stones of North Africa,” but to Moroccans they were the sound of an entire generation in a charged moment of global pop culture.

Cheikha Remitti: The Voice of Rai Music In Algeria

Arts

Culture

Born in a village in northwest Algeria, Cheika Remitti sang high-energy songs of love, loss and society that pioneered rai music. Beloved by fans for more than 60 years until her death in 2006, her influence and popularity endure.

Sitar Master of Maryland

Arts

With a lifetime of training from leading sitar virtuosos, Alif Laila is one of few women to achieve international recognition with the mesmerizing instrument whose sound evokes the musical identity of the greater Indian subcontinent. She is as passionate about music as she is about encouraging other women.