The Little Publisher That Could: Eland Upcycles Travel Literature

With more than 150 published works, Eland Publishing reflects a worldly eclecticism, from reprints and re-releases of biographies to letters and even comic novels. The London based publishing house has for 40 years brought new life to travel writing.

Travel writing is notoriously difficult to define. Travel writers even more so. Some could be called writers who travel—Jan Morris, Ibn Battuta, Robert Louis Stevenson; others are travelers who write, like Gertrude Bell, Marco Polo and Jack Kerouac.

Travel writers come from all walks of life. The celebrated United States journalist Martha Gellhorn often described places and travels amid reporting on war. Ernest Hemingway, to whom she was married to for five years, wrote travel as fiction. Former US Poet Laureate Billy Collins declared the highest form of travel writing to be poetry.

Cheap airline tickets and social media have forced travel writing to re-examine its origins and purpose, precipitating an identity crisis in the genre. Gellhorn, it turns out, plays a role in the story of how for 40 years, one small London publisher has brought new life to travel writing, however the term may be defined.

Three flights of stairs above an Italian restaurant on Exmouth Market, a cheerful street in Clerkenwell, husband-and-wife directors Barnaby Rogerson, 62, and Rose Baring, 61, run Eland Publishing out of a cluttered attic filled with books. From there they oversee Eland’s modest output, each year publishing only a handful of six to eight titles and selling a similarly modest 35,000 or so books in total.

“We don’t define anything,” says Rogerson from his chair amid the stacks of books. Travel writing, he says, is “a highly adaptable form” that looks outward. “Our readers relish the spirit of place and like to understand other communities.”

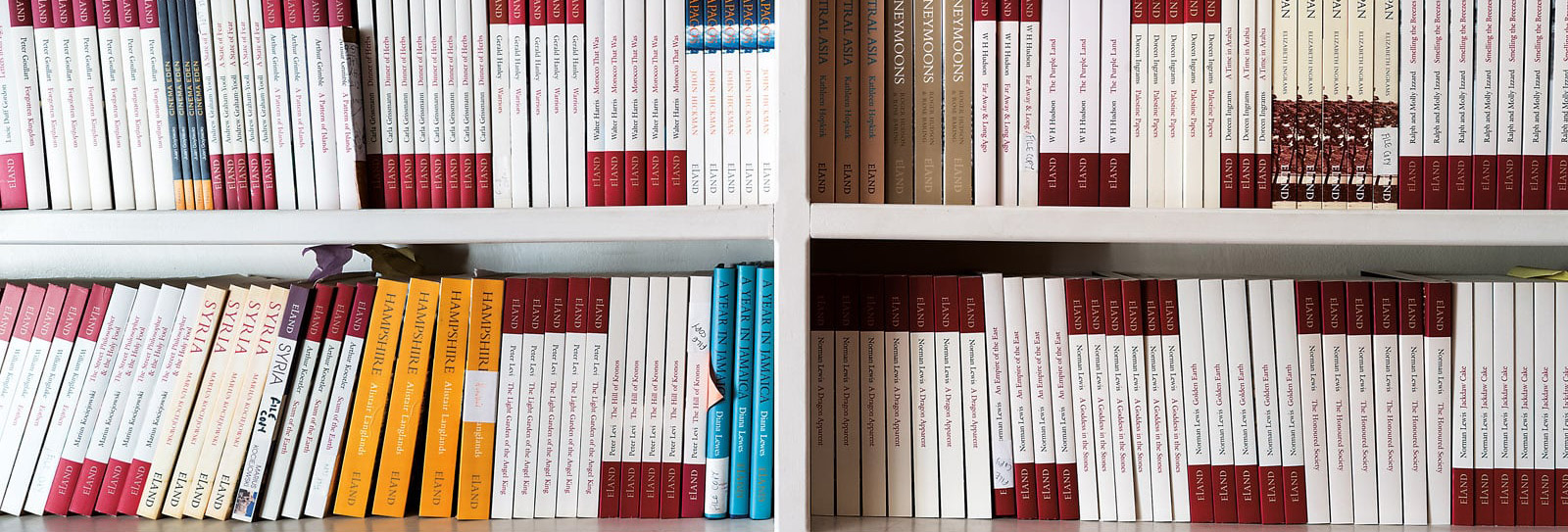

Eland’s list of more than 150 published works over its four decades reflects a worldly eclecticism. A book of letters from Istanbul written in the early 18th century by Mary Wortley Montagu sits alongside a 1990s comic novel about life in Jamaica, One People, by Guy Kennaway. British officer Ralph Bagnold’s 1935 account of desert exploration, Libyan Sands, shares its shelf with Sybille Bedford’s travelog about Mexico, A Visit to Don Otavio, and Veronica Doubleday’s tales from 1970s Afghanistan, Three Women of Herat.

“We look for books that are not defined by heroic adventures but the ability to listen,” Rogerson says. “We relish books that take each culture on its own value and plunge you amongst cattle nomads with the same energy that other writers might devote to interviewing presidents. Our principal resource is our readers, who are often much better read in specific regions than those who work in the Eland office.”

“Our readers relish the spirit of place and like to understand other communities.”

—Barnaby Rogerson

Caroline Eden, whose forthcoming Cold Kitchen is set to extend her award-winning series of books based on food cultures of Western and Central Asia, names her own Eland favorite: The Caravan Moves On, by Turkish adventurer Irfan Orga, originally published in 1958 and reissued by Eland in 2002. Eden regards the story of Orga’s stay with Turkey’s nomadic Yürük people as “an examination of modernizing Turkey, ... a snapshot of a world that is much changed,” and, she adds, “that is very Eland.”

“We’ve got a passionate, informed readership,” says Rogerson. He and Baring receive dozens of recommendations of books now out of print that readers would like to see made available again. For example, he explains, Baring’s stepsister, who at the time was in Sri Lanka as an anthropologist, “insisted that we look at The Village in the Jungle, Leonard Woolf’s novel published in 1913, for its insight into the lives of ordinary people in what was then British-ruled Ceylon.”

Similarly, he adds, “the first Eland I was absolutely sure of came from a friend’s recommendation to read the letters of the 16th-century Habsburg ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Ogier de Busbecq. And he was quite right. It is a most brilliant book, gossipy and unpretentious, but also intelligent, inquiring and deeply insightful.” So too was the genesis of the Eland title that briefly stood on top of the United Kingdom’s fiction bestseller list, The Ginger Tree, by Oswald Wynd, set in early 20th-century Japan. It came about, Rogerson explains, because a friend of Eland’s founder, John Hatt, insisted he read it.

Hatt, 74, established Eland in 1982. Witty and ebulliently curious, Hatt describes how in the 1970s he traveled across the UK as a publisher’s sales rep, “with a briefcase, going to almost every bookshop. … There was no section called ‘travel literature’ then. Lots of good stuff had gone out of print, and it was very unfashionable. There was a gap in the market. I thought it was worth starting an imprint that did travel.”

Hatt had—and still has—a home on Eland Road, a narrow parade of squat, 19th-century rowhomes in Clapham, a suburb of south London. He decided to name his publishing company Eland partly for the street but also because the eland is the largest antelope in Africa: “It was quite useful to have a colophon that’s an animal—think of Penguin,” he says.

Eland’s upcycling has been honed to rescue quality from obscurity.

For almost 20 years, Hatt ran Eland from his tiny home office while also working for part of that time as travel editor for Harpers & Queen, the predecessor of Harper’s Bazaar. His first title under the Eland name, A Dragon Apparent, described a journey through Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia in 1950 by the British writer Norman Lewis. “Here was a book I loved, and it was out of print. That was a beginning,” Hatt says. He bought the rights to it cheaply enough, and went on to do the same for other books by Lewis, whose working-class roots and modesty made him an outsider to London’s literary establishment.

Lewis often wrote about marginalized peoples and cultures: His 1968 newspaper article reporting government atrocities against indigenous people in Brazil led to the creation of the global human rights organization Survival International. His account of wartime Italy, Naples ’44, described by the Guardian as “hauntingly comic,” became another Eland acquisition, named by journalist Gellhorn in 1994 as her personal favorite travel book. The regard went both ways: Hatt reprinted Gellhorn’s 1978 collection Travels with Myself and Another, and the two became close friends. Writing in The Independent, the novelist Nicholas Shakespeare declared that Gellhorn “adored [Hatt] not simply for resuscitating her fiction, but [because] Hatt embodied self-sufficiency.”

“My golden rule,” Hatt says with vigor, “is never, ever think about whether the book will sell. You have to completely rule that out. You’ll only survive in the niche if you do what you think is good.” He lands on the example of The Ginger Tree: Refusing to heed warnings about the book’s seeming lack of commercial appeal, he published a new edition in 1989 just as a four-part television adaptation also aired in Britain, Japan and the US.

That market instinct served Hatt in other travel-related ventures. In 1996 he bought the Internet domain cheapflights.co.uk and built such a booming business that he was able to sell three and a half years later, becoming a dotcom millionaire at the age of 50. But the experience, he says, “exhausted” him. “I wanted to start my life again. So I looked to sell Eland.”

Rogerson recalls the same period. He describes how he had “adored Eland from a distance,” writing admiringly to Hatt from his university years—where he and Baring met—after reading A Year in Marrakesh by Peter Mayne, originally published in 1957 and reissued by Eland in 1982, and Morocco That Was, by Walter Harris, originally published in 1921 and reissued by Eland in 1983. “I was very aware how little there was on Morocco for the general reader. Those Eland books opened not just a doorway, but all the windows too,” Rogerson says.

The couple stayed in touch with Hatt while traveling extensively, including research for guidebooks to Morocco, Tunisia, Cyprus and Istanbul. Children forced a change. Having settled, Rogerson determined to “inhabit and really immerse” himself in Islamic history, writing a biography of Prophet Muhammad “for an ignorant Westerner like myself,” as well as narrative histories of North Africa and the Ottoman Empire and Meetings with Remarkable Muslims, a touchingly personal collection of pen portraits.

Rogerson and Baring took over as Eland’s owner-directors in 2001. (“There couldn’t have been nicer buyers,” adds Hatt, who retains a small percentage of the business.) The duo opened the office in Exmouth Market, a short walk from their home, just as the street was gaining new life with restaurants and independent businesses. Rogerson—author of a dozen books yet self-defined as a “barrow-boy trader” from a “book-hating family”—leads on sales and marketing, while Baring, a psychotherapist who admits “I would never have become a publisher if I hadn’t hitched my wagon to Barnaby,” oversees design. Behind the scenes, a “hidden team” of remote-working freelancers handles Eland’s publicity, bookkeeping, typesetting and other roles.

Gellhorn and Lewis, along with the Irish writer Dervla Murphy—“those marvelous mavericks,” in Rogerson’s words—remain at the heart of Eland’s wide-ranging list, platforming what Shafik Meghji, author of the 2022 book Crossed Off the Map: Travels in Bolivia, calls “authors who have often unjustly drifted from the public consciousness.” Meera Dattani, former chair of the British Guild of Travel Writers, praises “independent, ethically minded publishers like Eland [for] celebrating knowledge of the way different cultures live.”

Yet challenges arise with changing times. “Who gets to tell the story of a place?” asks Jini Reddy, author of Wanderland, a pastoral travelog focused on landscape and nature, published in 2020. “The condescension of colonial-era tales wearies me,” she says.

“Anyone who champions historic travel writing, which in the English-speaking world was often written by a very narrow demographic—usually men, and always from the wealthier ruling classes—must be mindful of the skewed perception of the world this has constructed,” adds Tharik Hussain, author of Minarets in the Mountains: A Journey into Muslim Europe, published in 2021.

“Making people realize there are millions of centers of the world” may be Eland’s mission, “but the trick as a publisher is not to be earnest about this. ... People learn through delight.”

—Barnaby Rogerson

Eland’s directors are alive to the issue. “A future Eland has to be much more diverse, not a whole lot of white writers,” says Baring. “I’d love to see voices on the page from much further afield than we have.”

Rogerson concurs, speaking of trusting readers to grasp who is writing for whom and out of what context. Eland’s mission, he says, is “making people realize there are millions of centers of the world. It doesn’t have to be Washington, Paris, and London. [If] you understand that Yemen, say, has connections with Indonesia, Malaysia, East Africa, suddenly you see the world not centered from power points. There is no superior culture. But the trick as a publisher is not to be earnest about this. You have to make every reader’s journey enjoyable. People learn through delight.”

For Rogerson and Baring, the next step is seeking to publish more travel in translation, particularly from non-European languages: Last fall they scouted possibilities in Arabic at the Marrakech Book Festival. Rogerson confirms that Eland has only published 12 new books over its four decades, and that process, he says, is “great fun, but it requires a completely different business model.” In contrast, Eland’s approach of upcycling old works—in effect rescuing quality from obscurity—has been honed to address gaps in public perception of the Islamic world in particular. This is a reflection in part of Rogerson’s own obsessions: Alongside selections from medieval Arab travel writers, Eland’s 2011 An Ottoman Traveller, for instance, comprises the only writing by the 17th-century Turkish explorer Evliya Çelebi in print in English. Looking closer to home, this year Eland will put out a memoir by Christian Watt, a 19th-century woman from a Scottish fishing family, as part of its efforts to publish more working-class narratives.

And while embracing ever-new horizons, growth is not, at this point, a goal. “The very act of remaining independent is a virtue every morning,” Rogerson says. “We’re like a farmer with 70 acres from which he knows he can feed his family,” he adds. “We don’t want to grow. We want to carry on.”

About the Author

Andrew Shaylor

Andrew Shaylor is a portrait, documentary and travel photographer based just outside London and has visited 70 countries. He works with a variety of magazines and has published two books, Rockin’: The Rockabilly Scene and Hells Angels Motorcycle Club.

Matthew Teller

Matthew Teller is a UK-based writer and journalist. His latest book, Nine Quarters of Jerusalem: A New Biography of the Old City, was published last year. Follow him on X (formerly Twitter) @matthewteller and at matthewteller.com.