How Historical Paintings of Taj Mahal Changed Perceptions of India

The depiction of the Taj Mahal in the works of Indian and British artists in the 1800s helped bolster enthusiasm for the country & rsquo;s rich culture, architecture and society. One such painting, & ldquo; The Taj Mahal by moonlight,& rdquo; stirred a bidding frenzy at a recent auction, and some experts argue that such paintings have helped change perceptions of India in the West.

Paintings of the Taj Mahal That Changed Perceptions of India Still Captivate Today

At a Sotheby’s auction in the fall of 2023, an Indian painting drew a bidding frenzy that made headlines. When the gavel fell the artwork had sold for $609,628—more than 10 times its original valuation.

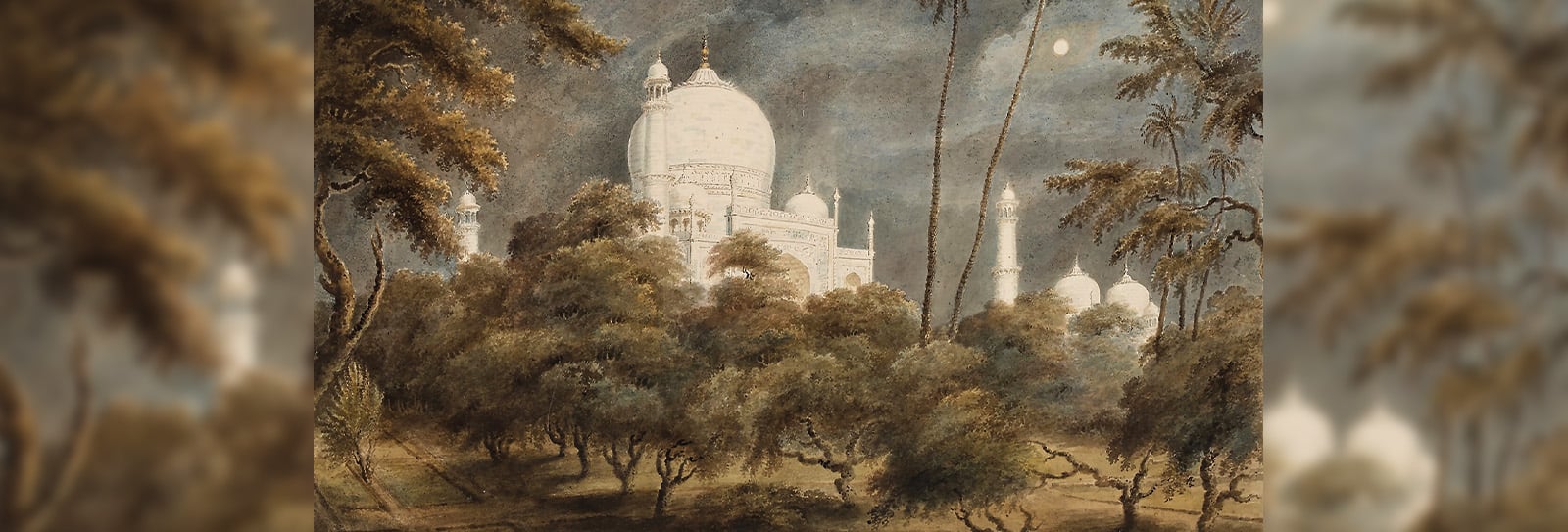

Artist Sita Ram’s 1815 chalk-and-watercolor-on-paper piece is as exquisite as its magnificent subject: the world’s most famous Islamic mausoleum. Visible are a tender gray-white sky and a swaying garden of lush mango trees. Between these layers of gray and green, like a creamy floating cloud, stands the Taj Mahal.

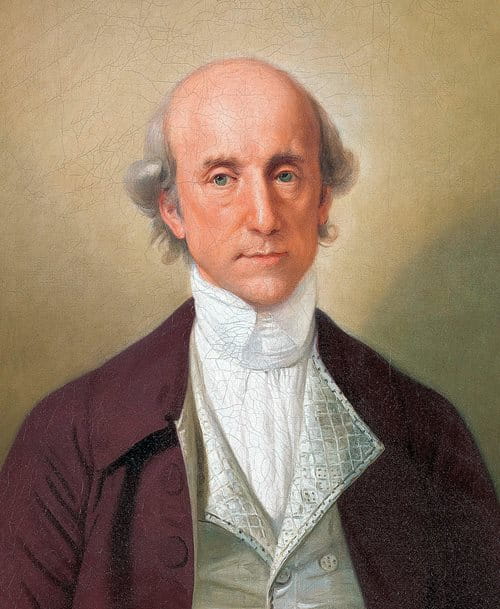

“The Taj Mahal by moonlight” is one of more than 200 surviving works that the Indian painter created on a yearlong trip with his employer, Warren Hastings, an official with the British East India Company, which at the time was the equivalent of the world’s biggest trading corporation.

The inspiration for the art that has transcended time corresponds to Hastings’ nightly visit to the Taj Mahal in 1815, which he describes as a once-in-a-lifetime experience, adding an epithet to the monument as “uncommonly striking.” He also confessed how the visit left an “impression of gratification” for him.

The Taj Mahal became not only one of the most important art subjects but a marker of a sophisticated India.

Hastings was not the only European to have expressed vivid emotions upon visiting the Taj Mahal. Over the centuries, explorers, merchants and painters professed their fascination with the monument.

Gradually the Taj Mahal became not only one of the most important art subjects but a marker of what would be viewed as a sophisticated India. It changed the West’s perception of the country as a “lesser civilization,” “a land of magic, mystery and a strange religion,” according to Isabelle Imbert, a specialist in pre-modern art of Iran and India. That sentiment resonated among other historians.

Emblem of Culture

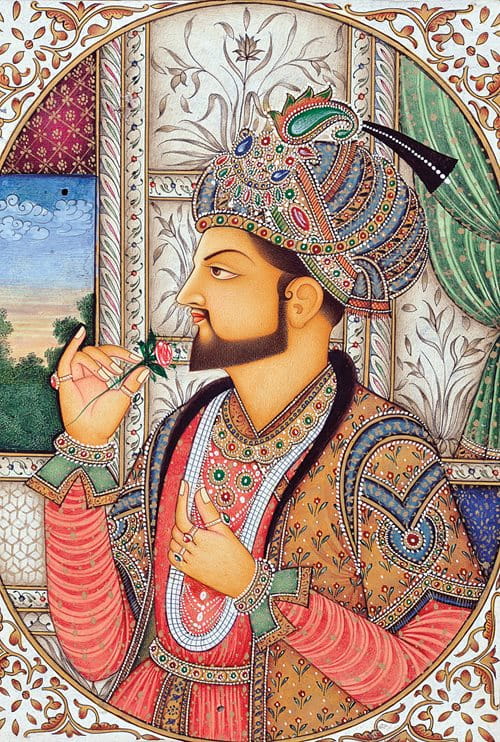

The European perception of India began changing in the 17th century with the growing admiration for the Taj Mahal, built in the north Indian city of Agra as an enduring monument of love from Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan for his favorite wife, Mumtaz Mahal. Construction on the primary marble structure began after she died in childbirth in 1631 and was completed about 12 years later.

The first words of praise came from Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a Frenchman with a penchant for Eastern cultures according to Emily Shovelton of the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London. Tavernier was a merchant with a prosperous career in precious gemstones and silk. He traveled to India six times between 1636 and 1668 and visited the Taj Mahal more than once. On his return to France, he published his travelogue The Six Voyages of Jean-Baptiste Tavernier at the behest of French monarch Louis XIV. The travel book enumerated all that he witnessed during his stay in India, from succession battles to Mughal life at large. He also described the monument’s striking architecture and beauty.

Once the travelogue was published, interest in the East grew among the elite, particularly after its rapid translation into English, German, Italian and Dutch.

Tavernier contemporary François Bernier also described his visits to the Taj Mahal with great enthusiasm. Bernier was the personal physician to the Mughal Court.

Bernier’s account, Travels in the Mogul Empire, dedicates multiple pages to his visit to the Taj Mahal. He says one is “never tired of looking at” it. Bernier also points to a travel companion’s reaction to seeing the Taj Mahal as “nothing in Europe so bold and majestic.”

Shevelton says “Bernier, writing in 1699, was stunned by the aesthetic beauty of the Taj Mahal and concluded that it deserved to be listed among the wonders of the world (Voyages 1699).”

Apart from conceiving the Taj Mahal as a grand mausoleum, Shah Jahan also intended it to be a unique piece of architecture.

Ebba Koch, professor emeritus of art and architectural history at the Institute of Art History in Vienna and a leading authority of Taj Mahal, affirmed the emperor’s vision of the monument as his magnum opus. She writes in 2005’s “The Taj Mahal: Architecture, Symbolism, and Urban Significance” that “the Taj Mahal was built with posterity in mind, and we the viewers are part of its concept.”

“We the viewers” would grow to include not only those who witnessed the feat of architecture in person but its artistic renderings as well.

The Catalysts

The late 17th century saw the rise of a hybrid artistic style called “Company Paintings” that were executed exclusively by Indian-origin artists, henceforth known as “Company Painters.”

“Artists were commissioned by an equally diverse cross-section of East India Company (EIC) officials and their wives, ranging from EIC’s medical and botanical staff to soldiers, civil servants and diplomats, missionaries, judges and discriminating women writers as well as by more itinerant “British travelers passing through India for pleasure and instruction,” historian William Dalrymple writes in his book “Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company.” “What all had in common was a scholarly interest in and an enthusiasm for India’s rich culture, history, architecture, society and biodiversity.”

For those who were receptive to India, the Taj Mahal acted as the gateway to their curiosity and enthusiasm; it was one of the most drawn architectural edifices.

Art historian Imbert echoes Dalrymple: “The art depicted more about the patron’s taste, curiosity than the artist’s choice, and when it came to western artists traveling to India, they depicted Taj Mahal because it was one of the most magnificent monuments in Mughal India [and] deserved to be depicted.”

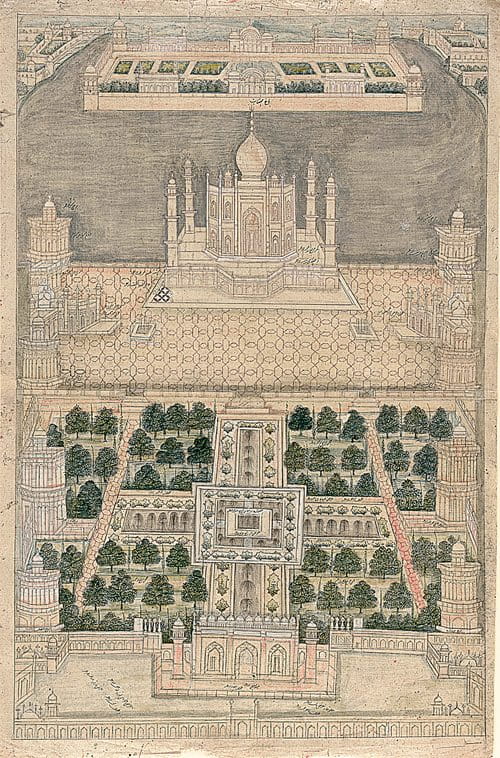

The first round of Company Paintings came about as part of a conservation initiative led by the British administration in the early 1800s. The project roped in draftsmen of Agra like Sheikh Ghulam Ali and Sheikh Latif to render exact drawings of Mughal monuments, including the Taj Mahal and Emperor Akbar’s tomb at Sikandra, both of which had fallen into disrepair. The idea was to use these meticulously drawn geometric pencil artworks as the structural plan for the conservation project.

“These resident artists at the Mughal court ... turned their hands for producing first their work for East India Company and then for the passing travelers.”

—William Dalyrimple

“These resident artists at the Mughal court in whatever capacity, as draftsman or architect or stone cutters as Sheikh Latif was, turned their hands for producing first their work for East India Company and then for the passing travelers,” Dalrymple says. “Judging by the number of copies, they seem to have developed an atelier, maybe a family atelier, which mass-produced this art in the 1820s and ’30s.”

Around the same time some of the first professional British landscape painters William Hodges and uncle-nephew duo Thomas and William Daniell arrived in India, but they didn’t share the same perspectives.

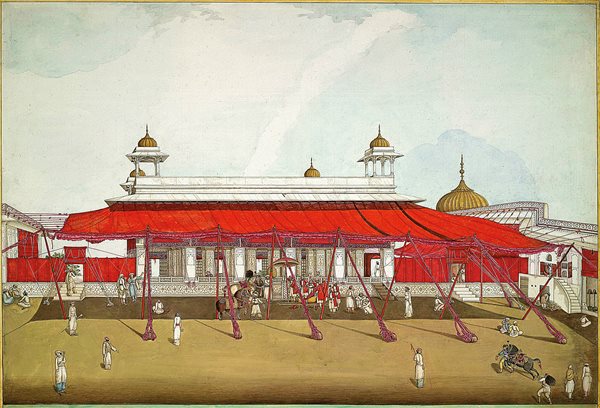

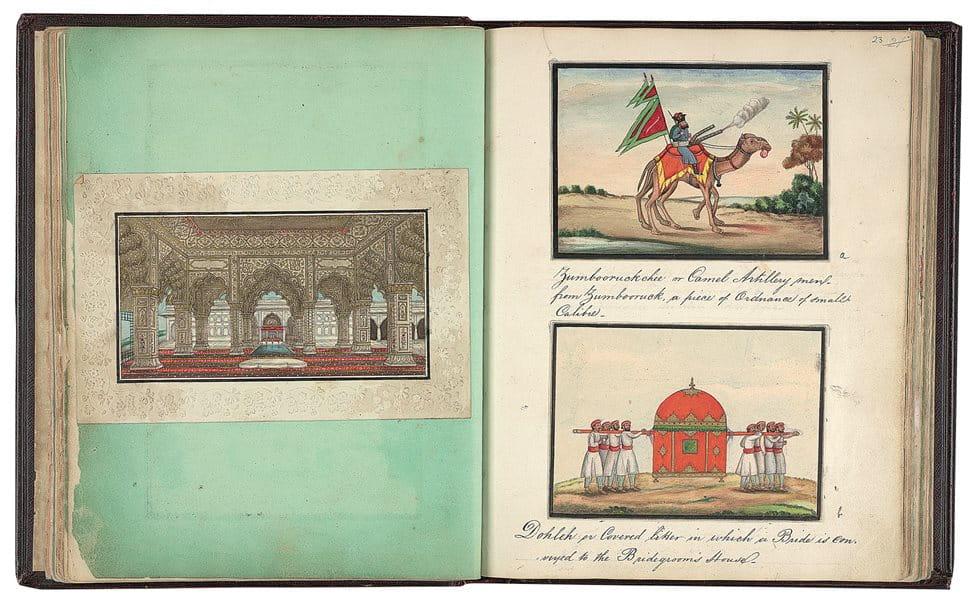

“Reminiscences of Imperial Delhi” consists of 89 folios containing approximately 130 paintings of Mughal and pre-Mughal monuments of Delhi, as well as other contemporary material, and accompanying text written by Sir Thomas Theophilus Metcalfe, the governor-general’s agent at the imperial court (1795-1853). Pictured are ink and colours on paper (1843) of the interior of the Diwan-i-Khas, LEFT; Camel Artillery Man, TOP RIGHT; and Bridal Dohleh, BOTTOM RIGHT.

Hodges did not want to give the Taj Mahal any extra attention. Consequently, he depicted Agra as the city of ruins. “Though he admired Taj fervently, he did not fulfill his promise to include a separate view devoted to it in this series,” notes Giles Tillotson, a scholar on Hodges.

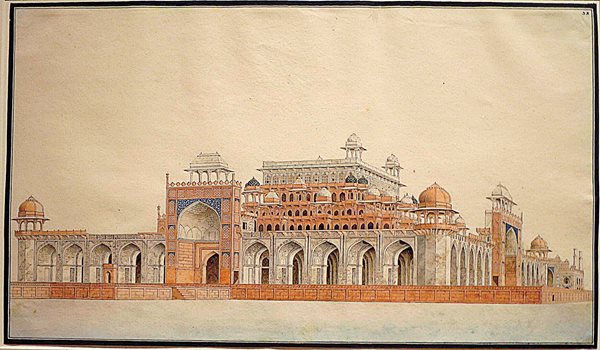

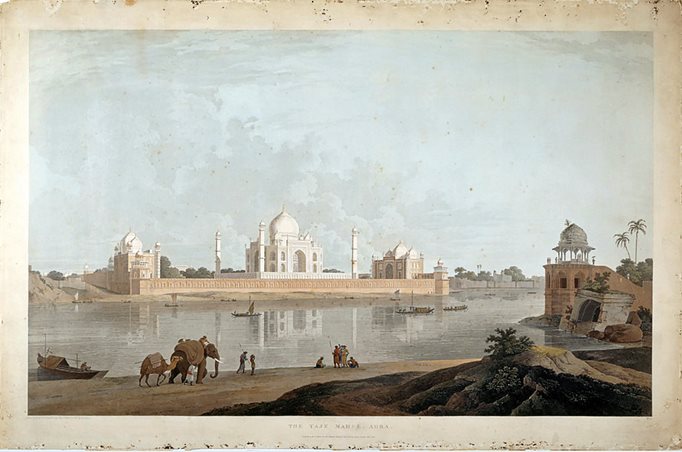

In contrast to Hodges’ apparent indifference, the Daniells, painted the Mughal monuments with great passion and are regarded as the most successful British watercolorists from the colonial era.

Between 1786 and 1793, the Daniells made several trips across the country with their retinue, and equipment including a camera obscura, to record scenes. During their North India trips, they were likely in contact with the best Company Painters of Delhi.

“The numerous annotations detailing the colors and shades for rendering the inlay work in marble facets of the tomb complex show that the Daniells regularly collaborated with native draftsmen, who probably prepared preliminary sketches, rubbings and etchings that served as a visual record for firming up finished sketches and paintings of the monuments,” writes Yuthika Sharma, an academic at Northwestern University specializing in the visual culture of the early modern and colonial period of South Asia.

Once the Daniells returned to England, their art (144 aquatints and six uncolored artworks) produced in India became hugely popular. Published in 1795-1808, the collection included beautiful renderings of the Taj Mahal—and remains one of the highlights of British colonial artistry. For the British commoner, this was possibly the break-even point to their ignorance of and disinterest in India.

An aquatint by English landscape painter Thomas Daniell depicts the Taj Mahal. Daniell traveled India with his nephew William Daniell, drawing scenes from across the country and later publishing them in a multivolume collection, Oriental Scenery, 1795 and 1808.

Indeed, Company Painters’ architectural drawings of the Taj Mahal, Agra Fort, Tomb of I’timād-ud-Daulah and the Red Fort of Delhi influenced perceptions of the country. The change was noticeably evident in the heightened commissioning of Indian art in the 19th century. Any European or East India Company official with an interest in India wanted to carry back the memories of their stay within the folds of a beautifully illustrated album.

Artistically valuable commissions culminated in two such albums, Delhi Book and Fraser Album, respectively commissioned by British civil servants Thomas Metcalfe and William Fraser. Established artists reproduced these “to cater to Europeans’ rising antiquarian interest in Delhi’s monuments,” Sharma notes.

That ”The Taj Mahal by moonlight” entices art lovers more than two centuries after it was created reflects the enduring power of both the piece and its subject around the globe.

You may also be interested in...

A Conversation With Art Collector Book Editors Peyton and Paul

Arts

In Arts of South Asia: Cultures of Collecting, coeditors Allysa B. Peyton and Katherine Ann Paul draw us into the personal, institutional and political dynamics surrounding objects that have journeyed from South Asia India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Bhutan to museums abroad and, in one case, undergone repatriation.

African Artists gain traction in the UK

Arts

The United Kingdom is experiencing a surge in demand for contemporary art of African origin. For artists of the African diaspora, the UK represents a new arena in which to showcase their messages through unique techniques and mediums. Interest in their work follows mounting pressure on museums, universities and other institutions to “decolonize” their curricula and collections.

A Quest To Discover Lebanon's Bibi Zogbé, Painter of Vibrant Hues

Arts

Except for a rare self-portrait, Bibi Zogbé painted flowers—exuberant and confident, as well as modern and symbolic, her paintings reflect her life between her native Lebanon and three decades in Argentina.