The Art of Saddling a Camel

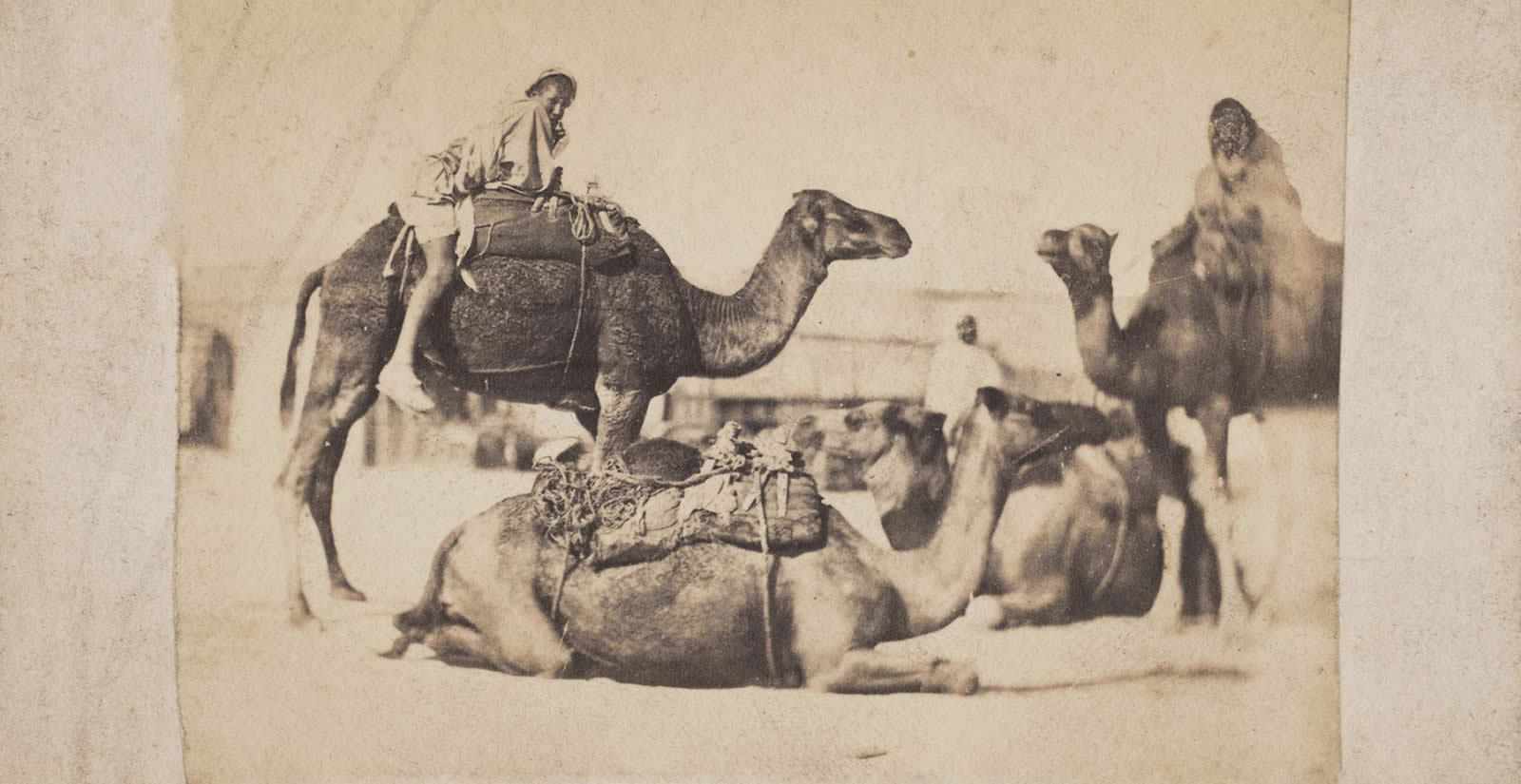

Since the earliest days of domestication, the camel’s hump—or humps—have challenged would-be riders. In Africa, Arabia, India and Central Asia, saddle designs have long expressed both utility, beauty and culture.

From the earliest days of domestication, the camel has presented a unique challenge: How do you ride an animal with a hump in the middle of its back?

“This is the way my father and grandfather did it,” says Adel Hamza, 55, who has offered camel rides to tourists at Egypt’s pyramids since he was a boy.

“We’re too busy working to study why something is the way it is,” says Mohammed Abd Elhay, a veterinarian in Cairo who has worked with camels.

Richard Bulliet, in his 1975 book, The Camel and the Wheel, points out that the first camel saddle was likely a blanket or an arrangement of mats, across which the weight of an equalized load on left and right could be placed.

The dromedary (one-humped) camel allows a rider to sit in front of, on top of, or behind the hump; the Bactrian (two-humped) camel is saddled between humps. It is not surprising, then, that camel saddles vary as much as the cultures that make them and the work the camels do, as well as the resources available for fabrication. Generally, in regions where wood is plentiful, one finds larger contraptions; in less resource-rich areas, designs tend to be minimalist.

It was probably in Babylonia and Assyria that camel cultures first came into contact with horse cultures, and the horse’s superiority in warfare likely gave rise to the North Arabian saddle, which is situated on top of the hump—the best position from which to fight with spear and sword. This saddle is supported by a pair of wool or canvas pads, one on each side of the hump, stuffed with grass, palm fiber or straw that level the contours of the camel’s back. Centered and closer to the camel’s head, the rider gains control.

Fully bedecked, a camel carrying a Bedouin can be quite a sight. On a trek a few years ago, my Bedouin travel companion Saleh, 55, and I met a young man riding high on a camel fitted with tassels hanging from every possible place. The halter had an ornate knot of goat hair over the bridge of the nose, and the meerika was shiny and new. I asked Saleh why our camel lacked such accoutrement. He replied, “I am old and married. He’s still young and looking for a wife!”

“Specialized craftsmen take three to four months combining wood and leather to create each saddle,” says Tuareg nomad Sidi Amar Taoua. Sometimes small copper bells hang from the saddle, and the varied artistic expressions give clues to region and tribe, he adds.

These technologies are far from all. As the roles of camel cultures diminish worldwide, the art and engineering of camel saddlery offers windows into the history of cultures that bear a deeper gaze.

You may also be interested in...

‘Home’: Arab American National Museum Celebrates 20th Anniversary

Arts

Arab American National Museum Director Diana Abouali says the facility—which is marking its 20th anniversary in 2025—in Dearborn, Michigan, has aimed to create a home for Arab Americans by preserving and presenting the history, culture and contributions of Arab immigrants as well as their native-born children and grandchildren.

Grand Egyptian Museum: Take a Tour of the New Home for Egyptian Artifacts

Arts

The Grand Egyptian Museum has officially opened its doors, revealing treasures from the ancient Egyptians and their storied past.

How Gulf's New Museums Are Championing Cultural Memory and Heritage

Arts

The result of decades of planning, new facilities in Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Arabian Gulf reflect the region's cultural renaissance and effort to preserve its heritage.