A Palette in White

There is no official count of how many varieties of cheese the Arab world produces. Although each is unique, all are white. Don’t even begin to think that makes them boring.

“Cheese is milk seeking eternity.”

This is what Jordanian artisan cheesemaker Nisreen Haram says as she leans all her arm strength into stirring a waist-high aluminum cauldron of curdling milk. “It is milk poetry,” she adds.

I stand nearby as her cheese poem moves closer to eternity with each swirl, her hair and shoes covered in protective mesh, her waist wrapped in a pinafore as white as the curd. As she hovers in front of the cumbersome vat, I am beguiled by white: this basement room of all-white tile flooring and walls, the white tables covered with ingredients, all white, in organized rows.

Nisreen is not merely a cheesemaking traditionalist producing mainstream dairy varieties. She is a guardian of a centuries-old tradition of Arab cheese, a staple throughout the Middle East and North Africa to this day that is, almost without exception, white. In Nisreen’s kitchen, making cheese is an expression of Arab culinary culture. And because each cheese creation is unpredictable in its formation, she executes dual roles as maestro and spectator. Cheese, she explains, is complicated.

Nisreen is one of many milk poets in Jordan. They are not only cheesemakers, but also food activists, chefs and shepherds. Together they taught me how to love these monochrome cheeses, how to appreciate their complexity in spite of their limited color wheel. When one thinks of a cheese deli in Europe or the us, it’s a palette of yellows, oranges, blues and a few whites. But cheese at any grocery throughout the Middle East is as white as an artist’s blank canvas, with only the occasional spattering of nigella or sesame seeds. Call it minimalist at best. To outsiders it’s bewildering. Or boring.

“Just calling it ‘white cheese’ is offensive to cheese,” Nisreen warns me as the sweet aroma of warm milk envelops her kitchen.

Every Saturday Nisreen runs an open workshop in the basement near her cheese cellar, where she sells her cheese and encourages customers to sniff and taste to give their senses a chance to appreciate the complexity of Arab cheeses. The most-asked question by the often-European visitor: Why is every Arab cheese white?

Her explanation circles back to the environment and the land as many of her cheese lessons often do. The hot weather of Jordan, she says, creates a fast fermentation process. This prevents cheese from aging slowly, which is what changes the color.

There is no official count of how many cheese varieties are produced in the Arab world. However, one can break them down into three types: yogurt-based, fresh and fermented. Whether it is 20 or 200, these cheeses are often nearly impossible to tell apart at the deli counter. There is no off-white or ecru, no pearl or soft gray. There is only white cheese—and each offers its own unique flavor, shelf life and appropriate culinary pairing.

Nisreen begins to teach me the intricacies. My first lesson: Assuming that varied colors of cheeses indicate grades of quality is a sure mark of an amateur.

And Nisreen is no amateur. Educated and entrepreneurial, she views cheesemaking as one of the original farm-to-table experiences, and her craft underscores a greater mission to reinforce sustainability opportunities throughout the Levant by maintaining close ties to the land and its milk-yielding animals.

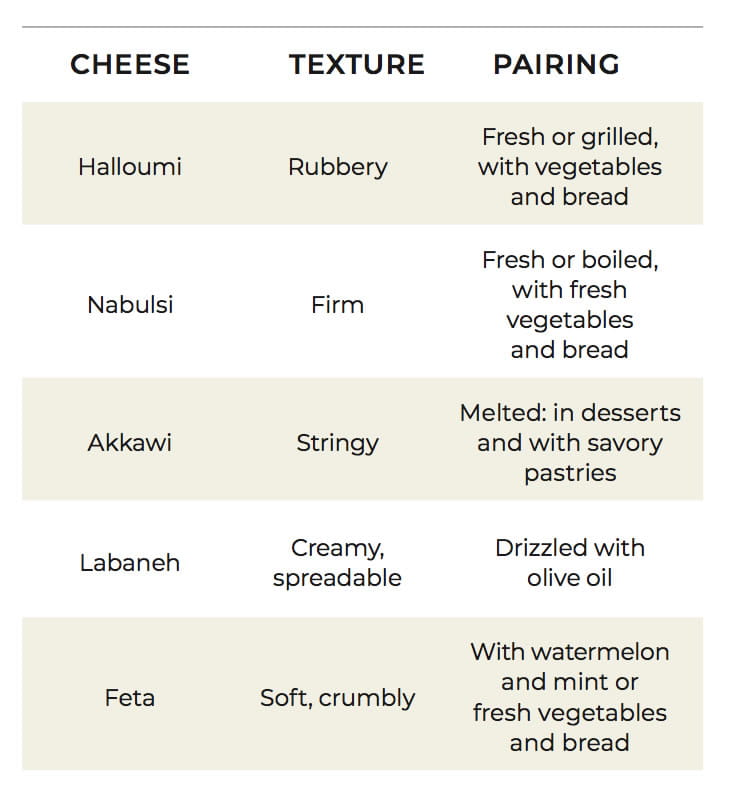

My second lesson: To experience the mystique of Arab cheeses, one must understand its relationships with other foods. Cheese is tethered to savory pastries and flatbreads, grilled appetizers and gooey deserts. It’s a staple of breakfast and supper tables, where it is often served among a tableau of cucumbers, tomatoes and olives. While it is true each cheese has its own flavor profile, truer still is that each cheese has its own texture profile that determines its purpose: some are eaten with bread, while others are exclusive to dessert. Yogurt-based cheeses, such as jameed, are most often used for sauces and stews.

Sometimes, two cheeses have the same purpose, but a slightly different texture, she explains.

Take, for example, the two most popular cheeses in the Levant: halloumi and nabulsi. These are both firm, salty cheeses that are often soaked in water for several minutes before being eaten to lessen the saltiness.

“Both are fresh cheeses. Neither melt. Both are preserved in brine,” explains Nisreen, describing fresh cheese as one that doesn’t ferment and, thus, over time its taste doesn’t change. “But with halloumi, when you boil the milk and the curds start to separate from the whey, you cut up the curds before pressing. That is what gives halloumi its unique squeak. With nabulsi, you just scoop up the curd and press.” (She really says “squeak.” Halloumi is, well, rubbery.)

While halloumi is generally assumed to have originated in Cyprus, some research indicates it more likely started in Egypt. Nabulsi gives away its origins in its name—the city of Nablus, Palestine, from which it came to Jordan with the country’s large Palestinian population.

After many hours with Nisreen, I’m prepared for the next lesson: to set out further across Jordan to learn about the ties among cheese, land and people.

Later, I arrive in Madaba, a bustling town surrounded by picturesque fields about 30 minutes outside of Amman. The small city is known for its fresh cheeses, as well as the Orthodox Byzantine Church of Saint George, in which a sixth-century mosaic map is credited as the oldest surviving cartographic illustration of the eastern Mediterranean. Tourists come to view the mosaic, and Jordanians come to sample local cheese.

In an area of scattered houses and gardens just off Madaba’s main road, Amubarak Abu Qoad, a local tribal leader, and his wife, Manal, run a women’s cheese cooperative in a small room built near their family’s large main house. Manal escorts me to the cooperative and offers a welcoming glass of yogurt-based jameed made from sheep milk. It’s pungent, to say the least. But it’s traditional, so I sip politely.

Even with limited lighting, it is easy to see the sheets of bright-white nabulsi cheese running the length of the room. Each sheet of cheese is drying on a large cake pan, readying to be sold and eaten. Half of the cheeses are peppered with black nigella seeds, which impart their subtly licorice-like flavor to the cheese.

“Nigella seeds have magical medical powers,” Manal tells me, listing the qualities of the seeds that include the prevention of stomach ulcers, relief from inflammation and many others. She tells me as if I had never heard this before, but I smile and listen, enchanted by her hospitality.

With a long knife, Manal lets me help her cut the tender sheets of cheese into cubes. These will later be placed in brine, then into five- to 10-kilogram tins called tanakats, in which the cheeses can keep for a year without refrigeration. The tanakats preserve the flavor, too, and this allows the cheeses to travel farther to potential buyers.

One buyer is Hazem Malhas, owner of a popular, Amman-based vegetarian café called Shams El Balad. He buys his cheese from Manal’s cooperative to help support sustainable agriculture.

“Nablus, along with Damascus, used to be the industrial center of this region, so the tanakats are probably a product of that,” he says. In his opinion cheese quality began to decline for larger cheese enterprises as cheese began being mass produced. In nabulsi cheese, for example, salt and mastic—a refreshing resin from the mastic tree that originally was added to sheep-milk cheese to remove the gamey animal flavor—are now used to mask poor quality, he says.

Hazem is also the founder of al-Hima, a not-for-profit dedicated to preserving an agricultural heritage that is also a throwback to the historic process of cheesemaking.

“We traditionally had the hima system here,” Hazem says, describing it as a sustainable grazing method in which shepherds rotated sheep around open, common pastures so vegetation would not be overgrazed.

Hima has been mostly lost in recent decades, however, in this region. A modernizing state is no longer as concerned with its shepherds, let alone its hima, even in a region celebrated as “the land of milk and honey.”

“We don’t have a history of drinking milk here,” he adds. On its own, he explains, milk was not easily digestible for Arabs throughout the centuries. Therefore, it was used for cheese and yogurt. So began the early tradition of white cheeses.

After several hours with Manal and her Bedouin assistants, her husband, Amubarak, drives me about 45 minutes to a mountainous grazing region. The land is open, vast and dotted with hundreds of sheep scattered across the green and brown expanses. His herd includes about 600 head of sheep, he says.

“This area is the home of the oldest sheep breed in the world, the Awasi,” he says with pride, adding that Awasis are most numerous in Syria, and probably originated in Iraq.

Spring, when the lambs are born, is the start and peak of the cheesemaking season, and it continues until August. The udders of the females (ewes) are at their fullest this time of year, and the land is at its most lush for grazing.

“In Lebanon and Syria, you have more rain, so there is one spot that a sheep can graze for a season. But Jordan is not so green. So sheep wander and eat different things on the ground, like olive leaves and seeds. The milk, and thus the cheese, will have different flavors, depending on what the sheep eat,” he says.

Amubarak maintains the hima system on this land that adjoins the east coast of the Dead Sea. Sheep are milked twice a day, and they are herded around the land by shepherd families from Syria, some of whom have been with his family for more than 60 years. Witnessing the intricacies of caring for the sheep, selecting the milk and understanding how it all plays into the land-based essentiality of the cheese, is revelatory. It is now that I could see all the ingredients coming together, many steps before the ingredients will be ushered into the kitchen. I spend a few hours with the sheep. Amubarak and I talk about hima. As the sun sets, Amubarak announces our departure.

Returning to Madaba, we approach a small, roadside house. It is another cooperative, and I immediately catch a whiff of the acrid jameed. Jameed is the Bedouin cheese, originally made centuries ago to be transported across the desert for long periods of time. It is reconstituted with water to form the sauce for mansaf, a lamb stew that is Jordan’s national dish.

Inside, Bedouin women are busy stirring cauldrons of milk in the crowded room. They have been working in shifts, all day and all night, to make enough jameed to serve the high customer demands throughout the year.

Drying yogurt is not solely a Bedouin concept. The closest example to jameed is shanklish, dried yogurt balls rolled in zaatar, the region’s popular mix of thyme, sesame seeds and sumac. With bread, the yogurt balls are broken up with a fork and mixed with tomatoes, parsley, onions and olive oil to temper its strength.

Because Jordan is comprised culturally of both Eastern Mediterranean and desert, parts of its culture favor Levantine ways, while other parts favor Bedouin ones. Jordan has also been a long-time haven for refugees, and through the years, with new influxes, new varieties of white cheeses have emerged.

Back in Amman, I visit Tamrkhain “Taymour” Shisani and his business partner, Dalal Shoumen, who own a specialty-cheese shop nestled in the back of an Amman industrial zone. Before taking me to the tiny kitchen upstairs, Taymour assists a customer who is sampling three kinds of labaneh, a fresh yogurt cream cheese. The difference in the labanehs is the amount of water removed from the yogurt, and Taymour’s customers have discriminating palates. I overhear a 30-something American Jordanian tell him while buying the driest of Taymour’s labanehs that his cheese is the best in town.

Taymour is only three years into his cheese business following a lengthy career as a civil servant followed by a stint in tourism. He’s now committed to his shop and to expanding his knowledge in cheesemaking, which currently includes learning to smoke cheese—a novelty in the Middle East.

We enter his kitchen, and he shows me his favorite blend of white cheese: the Circassian. He has two pots on the stove, one of whey from an earlier session and one of fresh milk that was hand delivered by a farmer earlier in the day. We wait for the milk to boil, making small talk in the interim.

“I like the patience making cheese takes,” he says, “and the precision. If you are two minutes late, it’s all over. Same for too much or too little salt.”

When the milk has curdled just right, he ladles it into individual sieves. These give the cheese its recognizable pattern. Then he mixes in the salt, and he covers the cheese with a plate, leaving them to drain. They will be ready in three hours, he tells me, and in the refrigerator they will last up to two weeks. Taymour also makes berm, a Chechen cottage cheese, and informs me he’s considering making the Arabic ricotta cheese, aaresh, later in the day by boiling the whey again and adding some yogurt. Unlike Nisreen and Manal, Taymour uses cow milk, even though it requires seven kilograms of cow milk to make one kilo of cheese as opposed to four kilos of sheep milk.

Taymour, like other cheese artisans, struggles to win over every customer because, like everywhere, many would rather buy inexpensive cheeses, unaware the quality is markedly less when they pay a cheaper price. I observe several customers enjoy his cheese, comment on its superiority and yet remain dissuaded by the price tag.

“I have a responsibility to you and myself to sell a pure, clean product,” he tells one customer. “I can’t stay in business if I charge less.”

He turns to me and sighs. “Everyone wants quantity, not quality,” he says, as the customer keeps trying to negotiate the price.

After venturing among the kitchens, shops and fields, I feel like I am beginning to hear the rhythm and rhyme of the milk poets. Though limited in appearances, these cheeses are anything but limited in taste and experience: sweet and salty, spicy and stinky, firm and supple—and everything in between. It is appropriate for breakfast, lunch and dinner; it pairs heavenly with dessert. Mostly, I learned the land, its milk producers and those shepherding the ingredients to the kitchens play no peripheral role. Arab white cheeses have thrived through the ages because of their ties to the land. It’s a culinary mythos that will stay safe as long as Nisreen and others like her continue to serve as its guardians. Maybe all the way into eternity.

“Nature leads you to the best cheese for you,” says Nisreen. “Most cheeses are accidents. They are serendipity for a particular environment.”

You may also be interested in...

Lebanese Dish: Cracked Wheat and Tomato Kibbeh Recipe

Food

Simply cooked line-caught fish with this beautiful tomato kibbeh. I don't know how you could top it.

How a Quest To Perfect Butter Chicken Rekindled Memories and Heritage

Food

What begins as a lesson in a beloved recipe becomes a journey through diaspora, friendship and the scents that tie us to places we’ve never lived.

Recipe: Chickpeas for Breakfast: Try Punjabi Chole Masala Recipe

Food

Chole masala is a popular breakfast dish of chickpeas.