Messages in the Maps

Long given short shrift by Western scholars for being more schematic than to scale, Islamic maps from the 10th to the 18th century were often sophisticated images, full of insights for anyone willing to set out and explore them.

Written by Graham Chandler Images courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Maps were like portals that enabled people to reach across the miles and the centuries to feel a sense of belonging.

—Zayde Antrim, Trinity College

Using a gentle two-finger pinch, Emilie Savage-Smith turns a page of an 800-year-old manuscript on display at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England. She leans forward and pauses, carefully reviewing each illustration.

“This entire treatise is one of the universe,” says Savage-Smith, professor of the history of Islamic science at the Faculty of Oriental Studies at the University of Oxford, describing the Book of Curiosities, a 13th-century compendium of Islamic maps. “It starts from the very outside where the stars are, and works its way down to the Earth. And then, when you get to the Earth, you get the diagrams of the winds, etcetera. This is the only treatise I can think of where the two are combined.”

The last few years of her three-decade tenure at Oxford has been dedicated to researching the Book of Curiosities, whose actual author remains unknown.

Savage-Smith, like other scholars in her field who have researched the book’s contents since its discovery and acquisition by the Bodleian in 2002, asserts that its maps and Arabic texts offer new insights for understanding the ways people understood the world at that time.

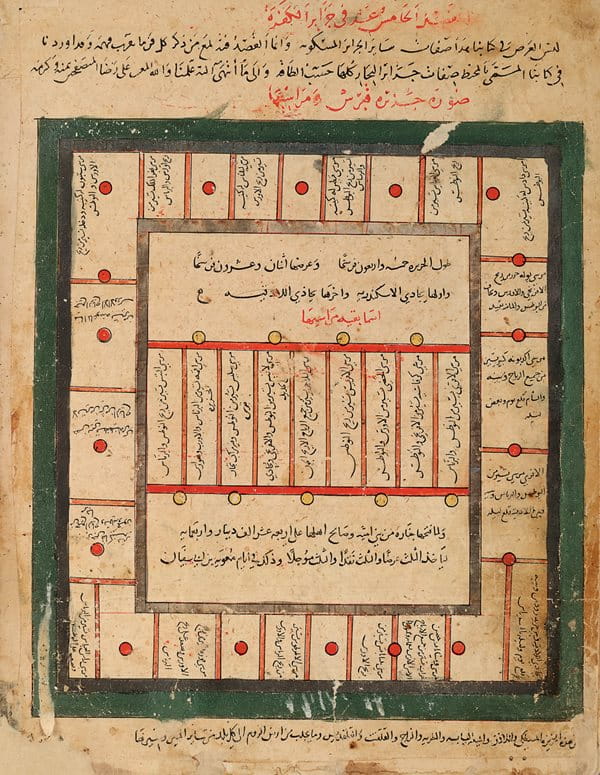

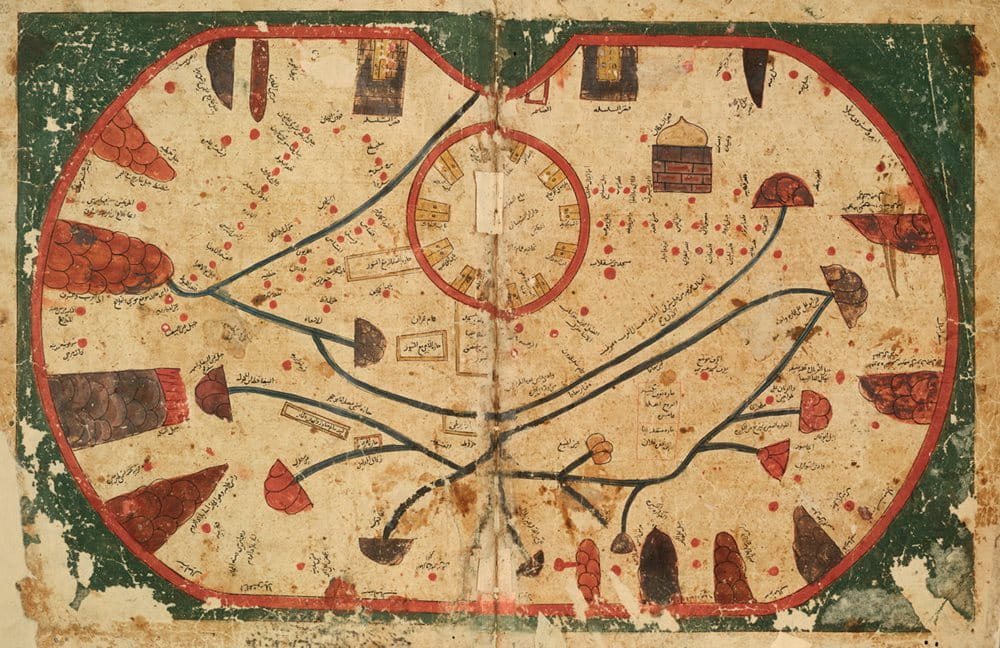

Its original title, transliterated from Arabic, is Kitab gharaib al-funun wa-mulah al-‘uyun (Book of Curiosities of the Sciences and Marvels for the Eyes), and it was first produced around 1200 ce. The Bodleian acquired this 13th-century ce copy through a London antiquarian dealer, and the library has since translated its texts into English and posted its images on the library’s website. In its day, the oversized book would have been placed on a lectern or tabletop, as it is too large and heavy to fit across one’s lap for casual reading. In front of Savage-Smith, the book appears larger still, its cartographic illustrations spanning a full 23 by 33 centimeters across the faded, brown pages.

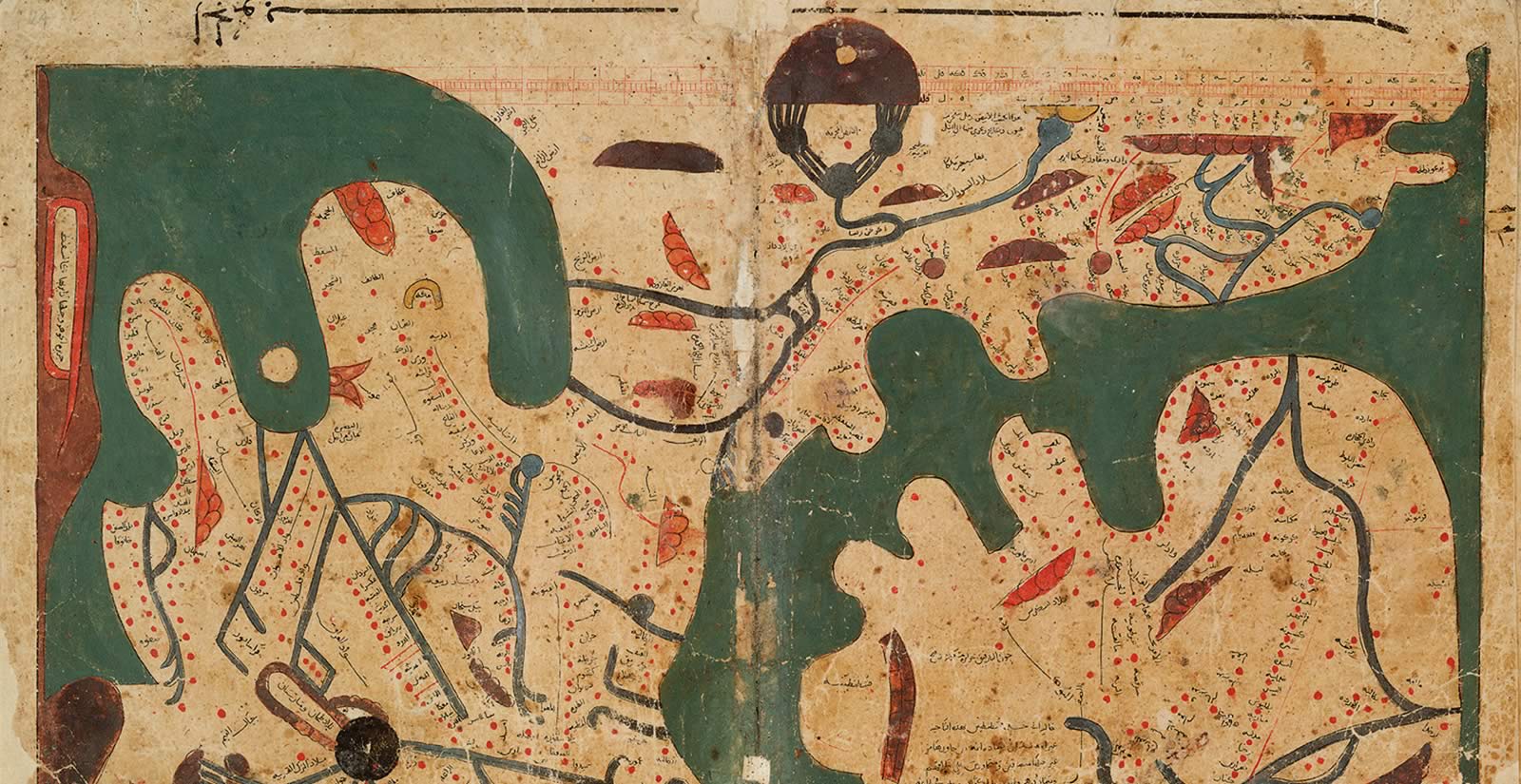

Maps inside the book boast expertly inked, black contours supplemented by brilliant blues, reds, yellows and greens in seemingly abstract, schematic renderings of lands and seas, fairly bursting with additional grids, charts, diagrams, inset illustrations and travel routes.

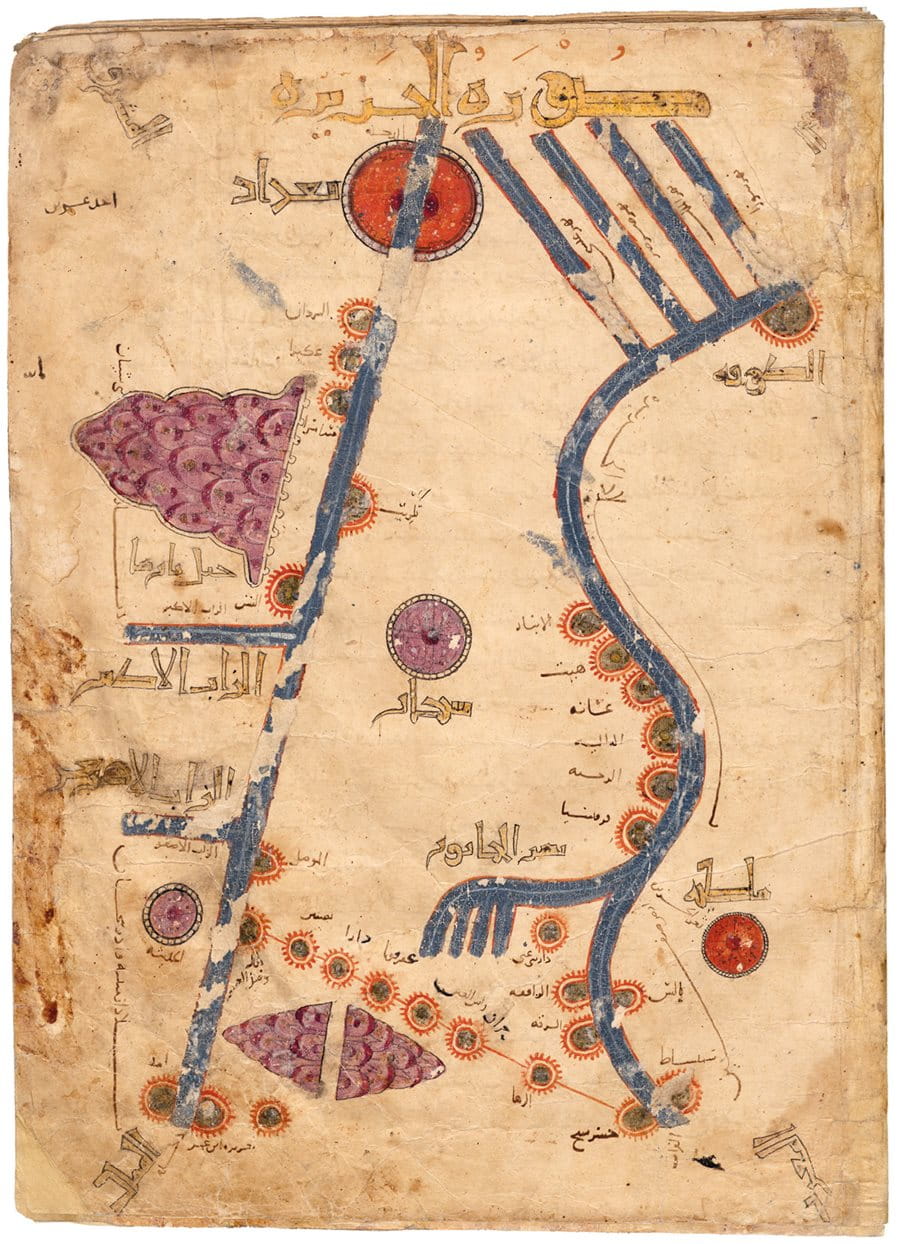

Savage-Smith notes that some of the book’s cartographic illustrations are particularly important—especially its large, rectangular map of the world. Its shape, she explains, is the only one of its kind to predate the Renaissance. Other maps in the book detailing rivers—the Nile, Euphrates, Tigris, Indus—and islands across the Mediterranean incorporate details that refer to culture, daily life and trade.

“One of the things you look for, for approximate dating, is the nature of the ink,” she explains. With Arabic manuscripts “it’s the red ink. The color of the red ink changes with time,” she says, adding that some of the map dating process requires scrutiny of materials.

In a time before the printing press, copying was done by hand. Maps in the Book of Curiosities were frequently copied, leading scholars to ask, “How did one prevent errors in the copies?”

Over time, with scholars examining multiple copies of the same text and maps, Savage-Smith says it has become easier to know which copies remained truest to their originals.

“You don’t know what possible changes the copyist might have introduced,” says Savage-Smith. “You have to guess. Obviously if a place didn’t exist at the time of the original, that would be clear. And that’s about all you can do. You can compare copies.”

There are other methods, too—including scent: “If a person is forging manuscripts or maps, it will have a different odor,” she says.

The Book of Curiosities offers its greatest breadth of information about Egypt, with many pages dedicated to the Nile Delta and, in particular, the town of Tinnis. It also makes positive references to the rulers of Cairo. Its script, ink and materials are consistent with those known from 13th-century Egypt. All suggest that the book’s unknown author was likely an Egyptian schooled in the geographical traditions of the time, which were flourishing most brilliantly in Baghdad, and that drew also upon earlier Greek work, notably that of Ptolemy.

“It is beautifully structured,” Savage-Smith says of the book.

It was in Baghdad that what is known as the Balkhi school of classical Islamic geography developed, named after the Baghdad-based, 10th-century CE polymath Abu Zayd Ahmad ibn Sahl al-Balkhi. His use of a world map and 20 regional maps supplemented with explanatory texts became a kind of template in the field. Other geographers of the Islamic Golden Age followed, including al-Istakhri, Ibn Hawqal, al-Muqaddasi and, in the 12th century ce, al-Idrisi.

Elements of Balkhi-style map models can be seen even in the Ottoman maps of the 16th and 17th centuries. They influenced early rectangular European atlases. But these and other Islamic styles of mapping generally declined after the Renaissance, and they virtually disappeared with the onset of European colonialism and advances in survey tools. Mapping standards shifted to European ones.

New research of Islamic cartographic illustrations, both in the Book of Curiosities and beyond, however, reveal how these maps demonstrate previously underestimated understandings of the Earth and the cosmos, and how maps were used for more than maritime navigation.

“Maps did not function as practical travel aids in the medieval Islamic world,” explains Zayde Antrim, professor of history and international studies at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, and author of Mapping the Middle East, published in 2018. “People sought written or oral directions. They consulted guides. They traveled in groups. They observed landmarks and celestial bodies. Maps, instead, emerged from travel. They were produced after the fact and for a different purpose,” which was to describe someone’s perception of a world traversed.

And maps in most medieval Arab atlases were not intended to stand alone, Antrim adds, pointing to the Book of Curiosities. With often elegant composition and texts using expensive materials such as silk and gold, these were made for those with enough status to read and study their importance.

“Maps did not function as practical travel aids in the medieval Islamic world…. Maps, instead, emerged from travel.”

—Zayde Antrim

“The written text constantly refers to the accompanying map, and authors clearly considered word and image to be complementary vehicles for conveying information. These were maps for book owners and book readers, not for a saddle bag,” Antrim says.

Another scholar ushering in new interest in these maps is Yossef Rapoport, reader in Islamic history at Queen Mary University of London. Together, he and Savage-Smith coauthored the 2018 volume Lost Maps of the Caliphs: Drawing the World in Eleventh-Century Cairo; Rapoport is also the author of Islamic Maps, published this year.

Soft-spoken and deliberate, Rapoport notes the insights the pair have gained from the Book of Curiosities.

“Maps of places we haven’t seen in maps before; places outside Africa, places in central India and in China, the routes of trade and propaganda, a maritime route that goes down the east coast of Africa. And more about waterways,” he says. He notes that the book’s maps often included secondary information, such as environmental descriptions of the rivers, for example, which would be of importance to sailors returning to the areas on the map.

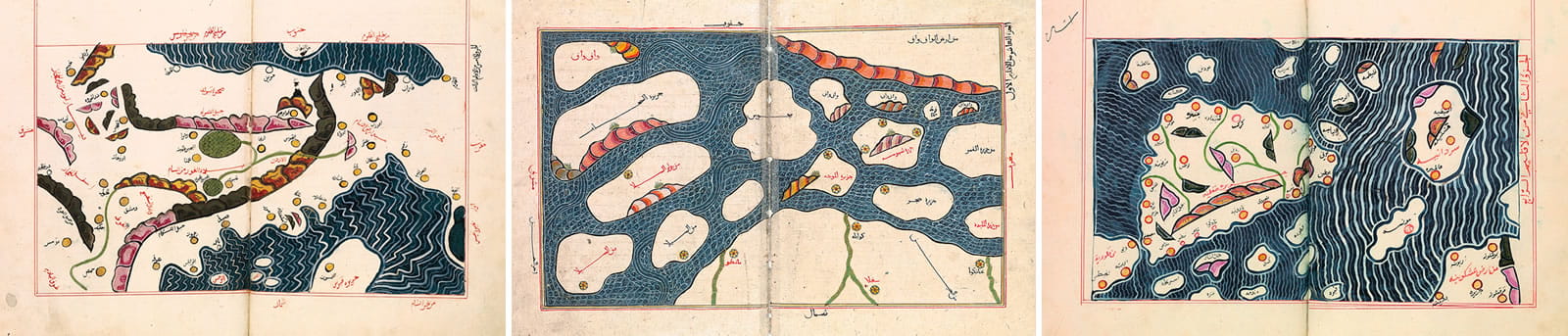

Rapoport carefully turns to the Western Sea map, a depiction of the Mediterranean Sea that would not look familiar to anyone looking at a map of the sea today.

“Here we see a completely different view of the Mediterranean space in a couple of ways,” he says, noting the map is the oldest-surviving example of a map with a geographic perspective looking at the coast from the sea, which was typically drawn the other way around in earlier maps. “It sports 118 islands in a dark green sea and 121 harbors and anchorages on its coast, each carefully labelled in Arabic script,” Rapoport says.

The Western Sea map is an important point in the history of navigation, as it presages the portolan charts of the later Middle Ages. It also depicts a correct sequence of harbor points, each describing the offerings of the area, such as water sources or, for example, how the port of Gaza can protect someone from the north wind. Other details show the capacities of the harbors, or how many boats can pass or dock.

“Its abstract nature is precisely because it is for mariners. It is clearly made for sailors, especially before the compass,” he says.

Maps in medieval Arab atlases generally relied on extensive explanatory texts.

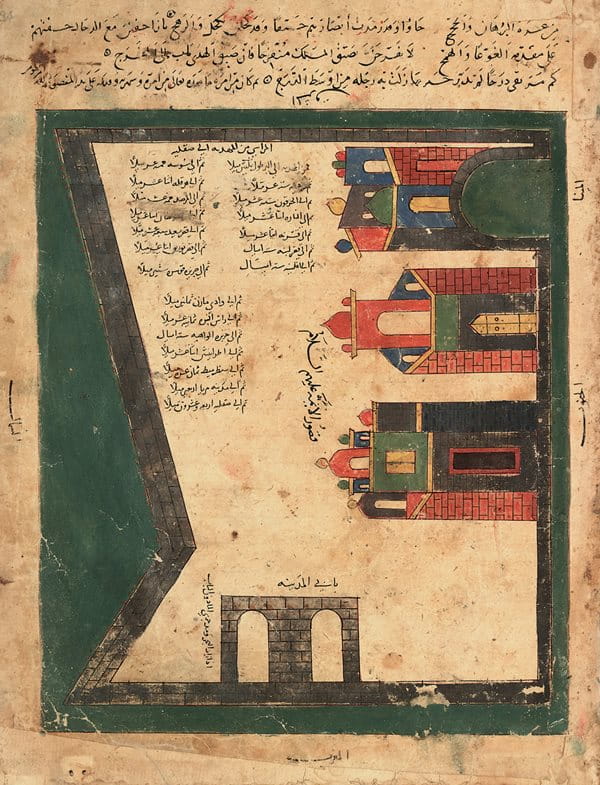

Rapoport turns to a map of Mahdia, the second capital of the Fatimid caliphate and today a city on the coast of Tunisia. It too was designed for sailors, he says, and one like this would have helped them recognize buildings as they approached the port.

“This would have been at the entrance of the harbor, but not the actual shape of the harbor,” he says, pointing to a trio of buildings drawn in detail on the map. “This appears to be the guard tower overlooking the harbor. These are the two palaces of the Fatimid king. They no longer exist, but we do know they were located around this area. We also know the gates of the city are in the right place. They were famous double gates. And the topography is right—here is a hill.”

Other maps cover much broader territory. The Indian Ocean map features much detail on the Horn of Africa, which Rapoport notes is “very distinctive. It tells you the name of the bay. This one is actually a translation of a Greek name. Here it says the bay begins with such number of miles,” he explains.

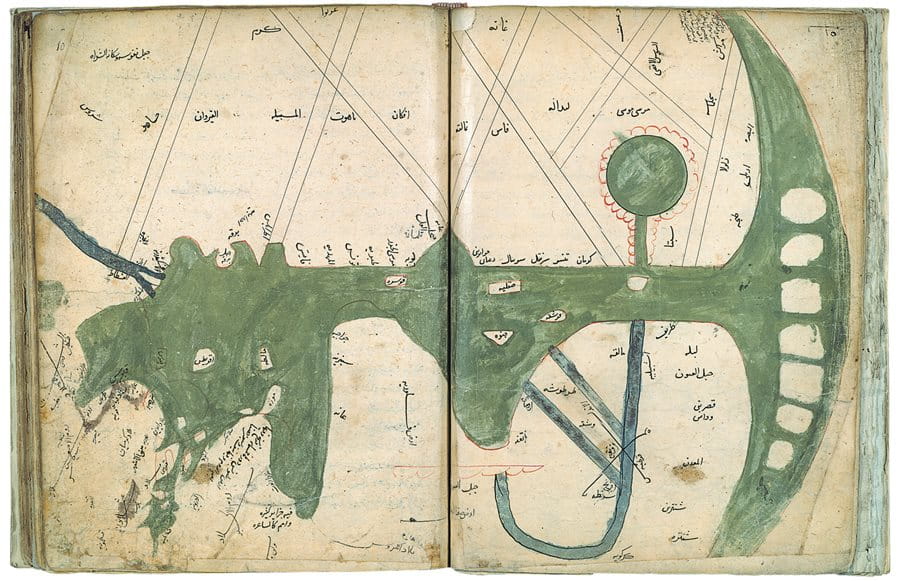

He turns to another map, this one in its own customized box: a map by al-Sharif al-Din al-Idrisi, known simply as al-Idrisi. Its leather cover and spine are cracked and worn, but inside, it has weathered the centuries well. The map colors remain brilliant—lapis lazuli blue for water, leaf green for salt water. The paint is still thick.

No matter how often Rapoport and Savage-Smith examine the maps, they say, they continue to discover new information about how these early Islamic maps set a standard for the geographic world.

Nadja Danilenko, too, is surveying the impacts of early Islamic maps focused on the practice of copy making over centuries. Now a fellow at the Freie Universität Berlin’s Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies, her doctoral dissertation was the first in-depth study of the oldest-surviving cartographic work from the Islamic world, the Kitab al-masalik wa al-mamalik (Book of routes and realms) by al-Istakhri. Like al-Balkhi, he lived in Baghdad in the 10th century ce and hailed from Persia; his cartography, too, produced a world map and 20 regional maps.

“I looked at the entire book, basically looking at the way he organized and arranged things and how he translated his ideas of space into the maps,” says Danilenko. “A combination of textual and visual.”

Then she set out to gather as many manuscripts as possible based on al-Istakhri’s work worldwide—she found about 60, the most recent dated 1898—to establish how the transmission changed through a millennium of copying.

Throughout, she found very few differences from the early versions. But that’s not always the case with map copying in general, she says.

“Al-Istakhri used lines that probably marked administrative borders and water bodies such as rivers and seas to delineate each region. Within the region, he used circles and polygons to represent cities,” she says, noting the cloudlike and triangular shapes he used for mountains and large circles for deserts. Blue bars represent rivers, and larger circles are seas. He captioned every item.

“As al-Istakhri arranged most items in a regular fashion, some symmetrically, some aligned etc. He aimed to communicate a sense of order through his maps.”

The maps were, she concludes, designed for anyone to use without needing expertise. Al-Istakhri used common icons for buildings and cities, for example, and he kept the references to other material easy to understand.

Illustrators as well as copiers had leeway sometimes to adjust the material if they were unable to read it properly or struggled to find the names of places they were not familiar with, she explains. Comparing details repeated from the early copies over time can get close to al-Istakhri’s original. Danilenko emphasizes, however, that differences do not always indicate mistakes.

“It is always important to realize the changes can come from new contexts, too,” she says. She found that previous studies of Islamic maps often tended to judge the maps’ scientific value rather harshly, in later, Western terms, and so she searched for ways to understand the maps on their own.

She turned to the fields of not only historical cartography, but also semiotics, the study of culturally determined signs.

“Usually you differentiate between three things: symbols, icons, and indices,” she explains. “Symbols are the most complicated because they draw on cultural connotations of things. For instance, if I use a flag, you have to be familiar with the concept of flags to understand what it means. So in using symbols on maps you presuppose a lot of knowledge—that’s crucial in deciphering maps.”

The way mapmakers have designed maps has always been informed by their own cultural, social or scientific perspectives.

The way mapmakers have designed maps has always been informed by their own cultural, social or scientific perspectives, and that is what makes analyzing these maps so interesting, she adds. “Because you actually try to get into the head of the person designing the map to see what he’s trying to communicate.” Her investigation determined the al-Istakhri map system was intentionally a simple one.

“We don’t find any flags or religious symbols or anything like that in his maps. Nothing representing a North African kingdom or an Andalusian kingdom. You only see topography and cities.”

This allowed the maps to carry through time, and still be read and understood today.

“Once you figure out the first regional map, you would easily understand the others. If you compare it to the other 19 regional maps, you realize that he depicted every region in the same fashion,” she says.

This simplicity and continuity, however, raises its own questions. For example, how representative of its own time is the information on a given map? Karen Pinto, an Islamic maps specialist, cautions that the maps “can tell us about the time period in which they were copied, and lead to greater knowledge of the period in which they were originally conceived,” she writes in her 2016 book Medieval Islamic Maps: An Exploration. “The problem is that with the exception of Balkhi virtually no biographical information exists on the other authors.”

“Maps are not territory,” she writes. “They are spaces, spaces to be crossed and recrossed and experienced from every angle. The only way to understand a map is to get down into it, to play at the edges, to jump into the center and back out again.”

As each map is newly questioned and appreciated, new insights follow, with each turn of the page.

“They are a rich source of historical data that can be used as alternate gateways into the past,” Pinto writes.

You may also be interested in...

How a Portuguese Town Rediscovered Its Islamic Roots

History

Arts

Thanks to children who kicked up little pieces of red ceramics while playing on a hilltop in 1977, the town of Mértola, Portugal, has taken its place alongside much of the rest of the country as it rediscovers its Islamic past. Years of excavations have turned Mértola, which lies near the border with Spain, into a destination for both tourists and researchers, and officials have applied to make Mértola a UNESCO World Heritage Site..jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5&cw=480&ch=360)

Photo Captures Kuwaiti Port Market in the 1990s

History

Arts

After the war in 1991, Kuwait faced a demand for consumer goods. In response, a popular market sprang up, selling merchandise transported by traditional wooden ships. Eager to replace household items that had been looted, people flocked to the new market and found everything from flowerpots, kitchen items and electronics to furniture, dry goods and fresh produce.

See How Researcher Zainab Bahrani Rethinks Narrative of Ancient Art

History

Arts

Zainab Bahrani of Columbia University photographs ancient statues and reliefs carved into the rocks of remote Iraq to create a database for conservators and scholars. The effort is “decentering Europe from histories of art and histories of archaeology.”