Robots of Ages Past

A century ago, a Czech playwright coined the word “robot,” and 500 years ago, Leonardo da Vinci designed a pretty good one—and he was far from the first. (Hey Siri, who was Ismail al-Jazari?)

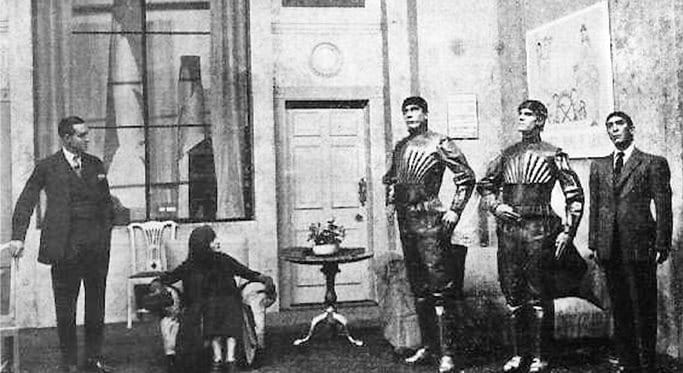

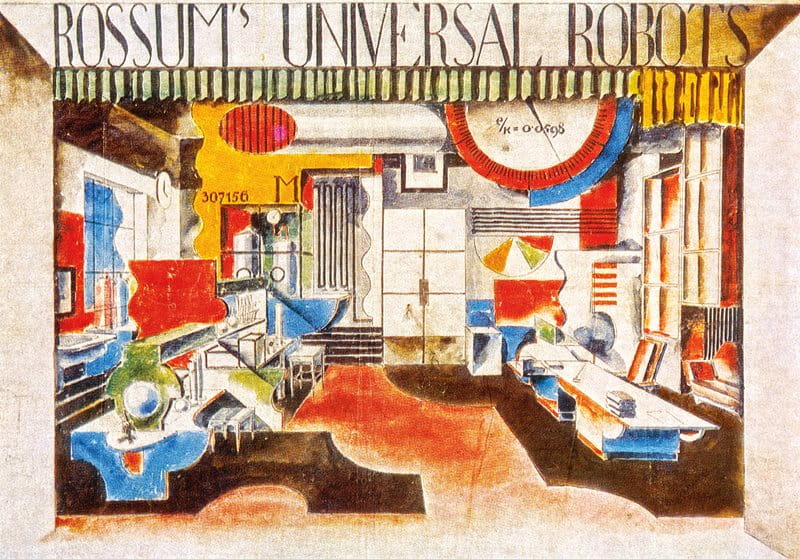

Two milestones are upon us that reflect the enduring human fascination with the idea of artificial counterparts—robots. The year 2019 marks the 500th anniversary of the death of Italian scientist-artist Leonardo da Vinci, whose designs and models of humanoid robots still inspire experts in robotics and Artificial Intelligence (ai). The year 2020 marks the centennial of the term robot itself, coined by Czech playwright Karel Čapek to describe artificial humans who could serve as a new class of workers.

Yet the ancestry of robots reaches back much further, to Egypt of the Pharaohs, classical Greece and the Islamic world of the early Middle Ages, upon which da Vinci based the development of some of his creations.

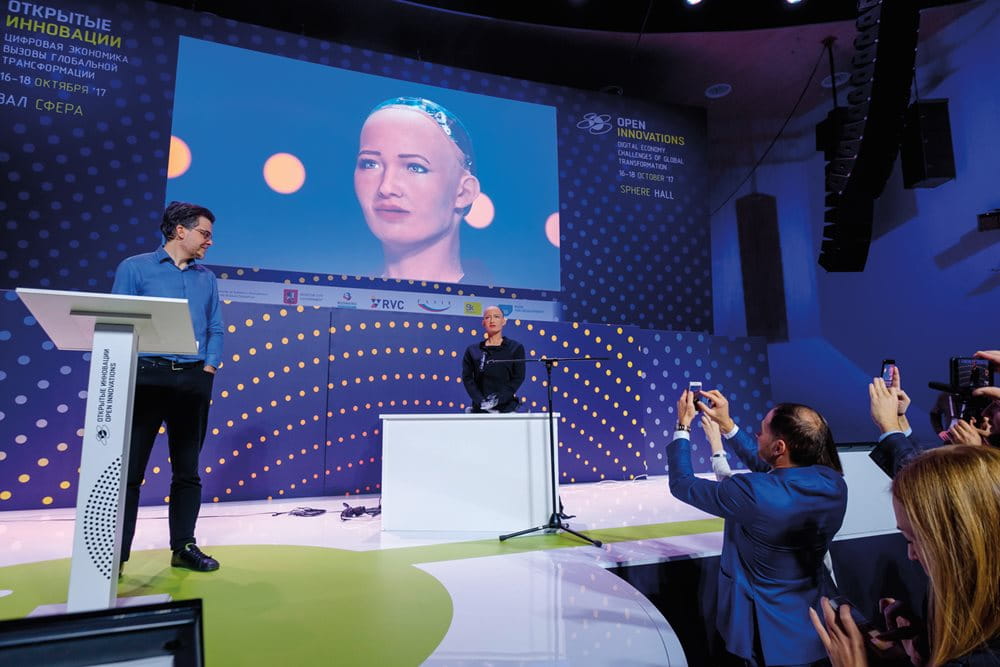

Today, smart is no longer a word used exclusively for people. From cars to vacuum cleaners to fully automated factories, robots—or programmable machines that accomplish tasks generally reserved for humans—are increasingly ubiquitous. Some are ai-enabled refrigerators that can order food for you; some are “digital assistants” such as Amazon’s Alexa and Apple’s Siri. Others are humanoid, such as Sophia, designed by Hanson Robotics with a face modeled on mid-20th-century actor Audrey Hepburn and equipped with ai and facial recognition to interact with humans. (In 2017 Sophia became the first robot ever to be granted national citizenship—by Saudi Arabia.)

Eventually, some futurists expect that some robots will look more and more like us, having synthetic skin and hair, individual (or not) faces and bodies. They will increasingly become androids, or virtual humans. Others will remain disembodied but capable of complex tasks (“Alexa, if it’s raining this afternoon, arrange a ride for the kids from school.”) And ever since the dystopic Metropolis in 1927, movies and television have asked whether robots would someday try to overthrow us (Bladerunner; The Terminator; I, Robot; Ex Machina) or whether they would be nice and helpful (Commander Data of Star Trek: The Next Generation; C3PO and R2D2 of Star Wars)?

Surprisingly, our ideas about robots being so futuristic are built on ones that began long, long before electric circuits and computer processors. The field of robotics began centuries—millennia—before the digital era. Ancient Egyptians built automatons that gave not just form but motion and voice to deities. Greeks speculated in early biotech. Muslims of the medieval scientific Golden Age devised complex automatons that helped inspire the drawings and designs of Renaissance polymaths like da Vinci.

Around the world, animated statues and automatons have appeared in early legends from the Americas to Africa to east Asia, often as minions or representatives of gods. And of these, the most influential to our world today were those that began in Egypt, in the second millennium bce.

French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero (1846–1916) tells us the Egyptians had “speaking statues,” images of their deities, made of painted or gilded wood with jointed limbs and voices operated by temple priests. The statues responded to questions and sometimes made lengthy speeches. One statue in the temple of Amun in Thebes was said to raise its arm and select the next pharaoh from among male members of the royal family. Maspero tells us the priests saw themselves as intermediaries between gods and mortals, and they firmly believed the souls of divinities inhabited the statues and guided them in producing voices and movements.

Asim Qureshi, an Oxford-educated tech entrepreneur who writes about the history of engineering, notes that Egyptians of that time “had enough knowledge of mechanics to develop a non-digitized [robotic] machine based on a system of ropes and pulleys.”

This Egyptian tradition appears to have passed north across the Mediterranean to Greece, where it infused myths and legends—and eventually science. Ian Rutherford, classics professor at the University of Reading, points out that “Egyptians and Greeks are known to have been in contact already in the second millennium bce, though we don’t know much about it. The picture becomes clearer from about 600 bce, when the sea-faring Greeks were frequent visitors to Egypt.”

Greek intellectuals of the day developed a solid understanding of Egyptian culture, according to Rutherford: “[They] saw it as a source of knowledge and esoteric wisdom. Some of them believed that Egypt had influenced Greece in the distant past; for the historian Herodotus, Greek religion was mostly an Egyptian import.”

Perhaps the oldest Greek tale involving ai and robotic figures is Homer’s eighth-century epic about the Trojan War, the Iliad. The inventor Hephaestus, god of metalworking, creates intelligent female automatons, made of gold, to assist him in his forge: “In them is understanding in their hearts, and in them speech and strength, and they know cunning handiwork.”

In the fourth century bce, Apollonius of Rhodes penned the Argonautica, the epic poem about Jason and the Argonauts, in which Hephaestus constructs a giant bronze automaton named Talos to protect Zeus’s beloved Europa from pirates on the island of Crete. Talos—in effect a “killer robot”—patrolled the beaches of Crete, circling the island three times a day.

Greek mythological notions of robots evolved into more-detailed (and practical) engineering concepts. Greek scientists and inventors developed techniques for simulating the actions of the human body.

Greek inventor Ctesibius of Alexandria, in the third century bce, pioneered compressed-air and hydraulic devices. He built an automaton operated by cams, or rotating mechanical links that transform rotary motion into linear motion. His robotic statue could stand and sit, and was used in processions. Though Ctesibius’s writings have not survived, later inventors and engineers adopted and improved upon his techniques.

Automatons have appeared in early legends from the Americas to Africa to East Asia.

Inventor Philo of Byzantium, who died around 220 bce, was known as “Mechanicus” for his engineering skills. His book Compendium of Mechanics describes a female robotic servant that could mix different liquids to make a drink when a cup was placed in her hand.

In the first century ce, Hero of Alexandria was influenced by Philo. He designed vending machines, automatic doors and an early steam-powered mechanism called the aeolipile, developed 1,700 years before James Watt’s engine, which used steam ejected through angled nozzles on a metal sphere to set the globe spinning. In his treatise On Automaton-Making, Hero describes an automated puppet theater that employs a combination of weights, axles, levers, pulleys and wheels to enact an entire stage play. A programmable robotic cart carried other robots on stage to perform for the audience. Falling weights pulled ropes wrapped around the cart’s two independent axles. Noel Sharkey, professor of ai and robotics at the University of Sheffield, compares this control system to modern-day binary programming.

The collapse of the Roman Empire and onset of Europe’s so-called “Dark Ages” created an atmosphere in which fantastic tales spread. Among them were stories of lost Roman treasure, hidden in hoards buried beneath hills and guarded by golden automatons.

These European stories were echoed later in an Arabic version, “The City of Brass,” an adventure tale in the One Thousand and One Nights. In this story—based on a historical account by Ibn al-Faqih—a military expedition sent by the Umayyad caliph finds an abandoned, walled city in the deserts of northwest Africa. With its lofty walls of brass, the city was reputedly built by King Solomon, and it was once a thriving capital until struck by an unknown catastrophe: All the inhabitants died, and they were mummified where they fell. The city’s beautiful queen, embalmed and dressed in elegance, was seated on her throne and guarded by two sword-bearing automatons. When an explorer tried to remove the queen’s jewels from her body, the automatons came to life, beat the man and beheaded him.

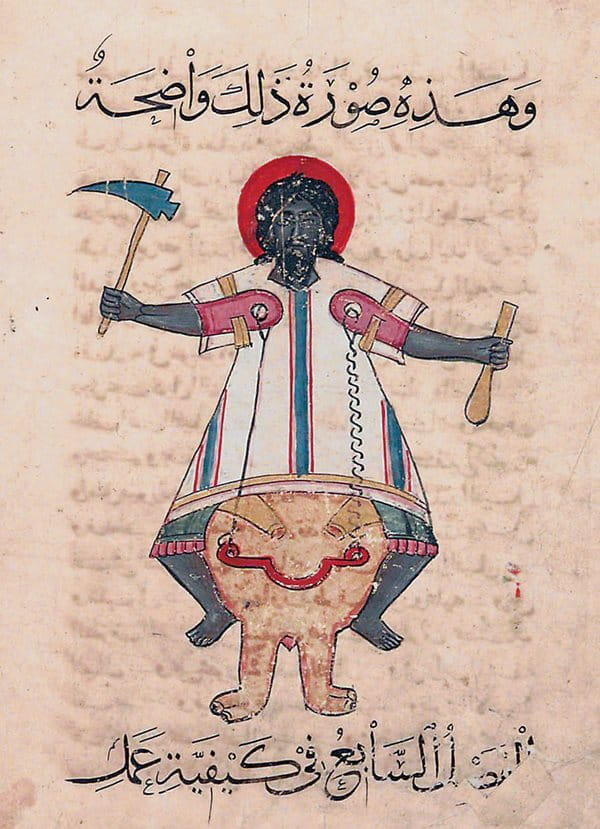

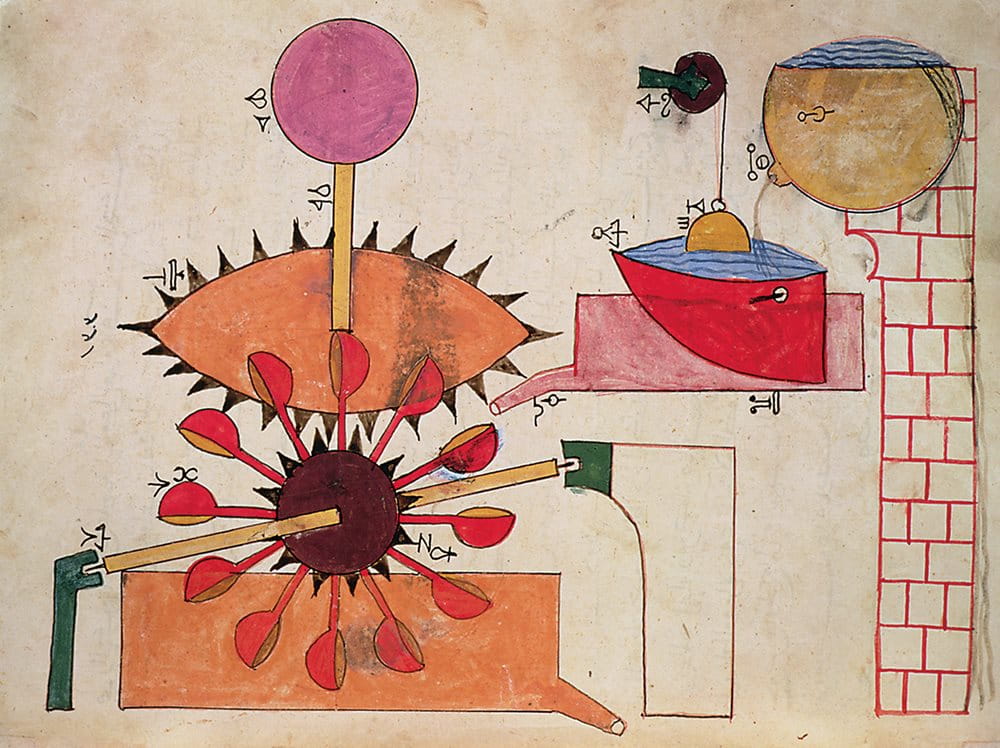

As Bryn Mawr historian E. R. Truitt describes in Medieval Robots (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), it was first the Byzantines and then the Arabs who preserved the mechanical arts in the Middle East following the fall of Rome. Around 850 ce, three Mespotamian brothers known as Banu Musa published The Book of Ingenious Devices, an illustrated work with designs of about 100 automated devices, including a water-powered organ. The Banu Musa, or “Sons of Musa,” were Ahmad, Muhammad and Hasan ibn Musa ibn Shakir, brothers from Khorasan who worked in Bayt al-Hikma (House of Wisdom), Abbasid Baghdad’s great center of higher learning. While their book did not deal with humanoid automatons, many of the technologies and automatic controls they developed were adopted and refined by Abu al-‘Izz ibn Isma’il ibn Razzaz al-Jazari, a towering engineering talent of the 12th-century ce.

Between the time of Banu Musa and al-Jazari, Arab and Islamic science flourished. A few manuscripts by the Banu Musa and al-Jazari have survived, but for many other engineering accomplishments, we must rely on accounts by historians, travelers and visiting diplomats.

Robotic achievements building on the works of Alexandrian scientists continued in Egypt during the Islamic period. One historical account tells us about 12th-century Fatimid vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah, whose guest hall featured eight robotic statues of singing girls, four made of camphor and four of amber, clad in fashionable clothing and jewelry. When the vizier stepped into the chamber, the statues bowed; when he sat down, they straightened up. This report, by Ayyubid historian Ibn Muyasser, is preserved in the writings of another Egyptian historian, al-Maqrizi.

The evolution of automatons grew in engineering sophistication over the ages, from the simple temple statues of ancient Egypt, employing basic levers and ropes for moving limbs and tubes for speaking from hidden locations, to the Greek robots, which used hydraulics, compressed air and basic cams to move body parts, to the automatons of the medieval Islamic world, which enabled more realistic movement with sophisticated cams, camshafts and even crankshafts, as well as advanced hydraulics and pneumatics.

An early cam was built into Hellenistic water-driven automatons from the third century bce. Both cam and camshaft would later appear in al-Jazari’s robotic creations. The cam and camshaft began appearing in European mechanisms in the 14th century.

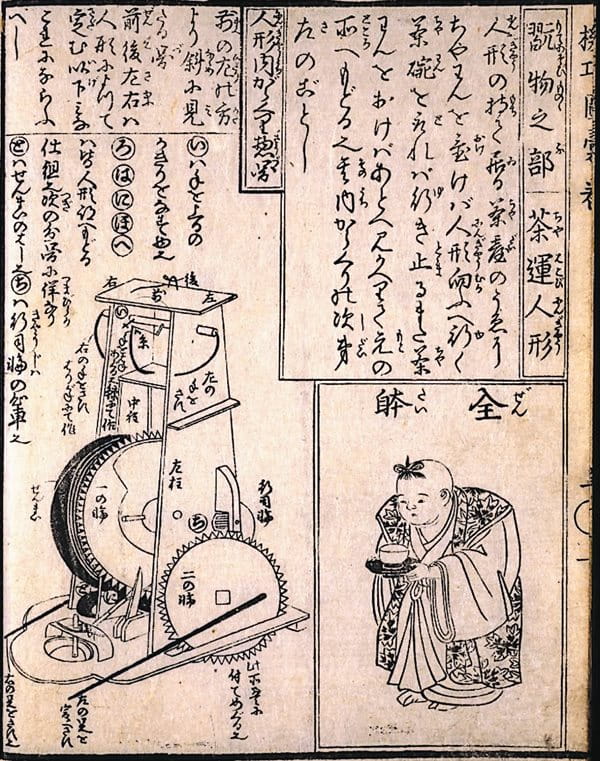

The crankshaft, the next stage in this technology, translates rotary into linear motion, and it is essential to much of today’s machinery, including the automobile’s internal combustion engine. Acknowledged as one of the most important mechanical inventions ever, the crankshaft was created by al-Jazari to raise water for irrigation while he served as chief engineer of the Atuqid dynasty. Written in 1206, al-Jazari’s Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices includes developments in the use of pistons and valves, as well as some of the first mechanical clocks driven by water and weights.

The Islamic world’s robotic designs found their way to Europe.

“It is impossible to overemphasize the importance of al-Jazari’s work in the history of engineering,” says Donald R. Hill, English historian and translator of al-Jazari. “The impact of these inventions can be seen in the later designing of steam engines and internal combustion engines, paving the way for automatic control and other modern machinery. The impact of al-Jazari’s inventions is still felt in modern contemporary mechanical engineering.”

As a result, some historians call al-Jazari the “father of modern-day engineering.” Salim al-Hassani of the University of Manchester, who chairs the Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation, notes that al-Jazari’s invention of an early programmable robot qualifies him further as “the father of robotics.”

The Islamic world’s robotic designs found their way west to Europe. “Throughout the Latin Middle Ages,” says historian Truitt, “we find references to many apparent anachronisms, many confounding examples of mechanical art. Musical fountains. Robotic servants. Mechanical beasts and artificial songbirds. Most were designed and built … in the cosmopolitan courts of Baghdad, Damascus, Constantinople and Karakorum. Such automata came to medieval Europe as gifts from foreign rulers, or were reported in texts by travelers to these faraway places.”

Western scientists of the Middle Ages pushed these engineering concepts even further. Today, their accomplishments sometimes reach us only through the filter of legend, where the technical overlaps with the preternatural.

Gerbert of Aurillac, a 10th-century French priest who studied science in Islamic Córdoba, was a pioneer in astronomical observation, introducing the armillary sphere and star sphere. He brought arithmetical calculation with the abacus and Arabic numerals to northern Europe. His scientific accomplishments resulted in legends that thrived a century after his death, including one claiming he had built a robot of sorts—a talking humanoid head—that could track celestial phenomena and foretell the future. Gerbert, a scientist and humanist long before the Renaissance, became the first Frenchman to head the Roman Catholic Church (999–1003 ce) , adopting the name Pope Sylvester ii.

Other medieval European scientists, too, were said to have created such “talking heads.” Scholars suspect the speaking-head concept originated in Arab folk tales. It became a powerful image in Europe and was linked in popular imagination with leading scientists such as Germany’s Albert the Great and England’s Robert Grosseteste and Roger Bacon.

The tale of Bacon’s “brazen head” is the best known of these, and it was featured in Robert Greene’s 16th-century play, Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay. Bacon made a human head of brass that could speak and function as an oracle. While the scientist slept, Bacon’s apprentice tried to question the brazen head. It spoke three times, saying, “Time is,” “Time was” and “Time is past.” It then fell to the floor, broken and evermore silent.

Gerbert of Aurillac's “talking head” could track the moon and stars; Roger Bacon's 16th-century “brazen head” spoke but once.

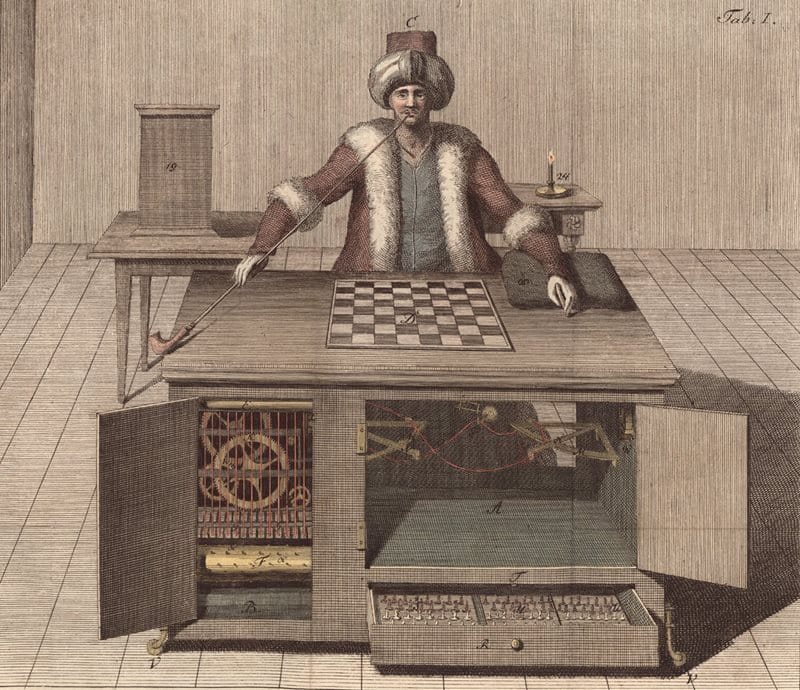

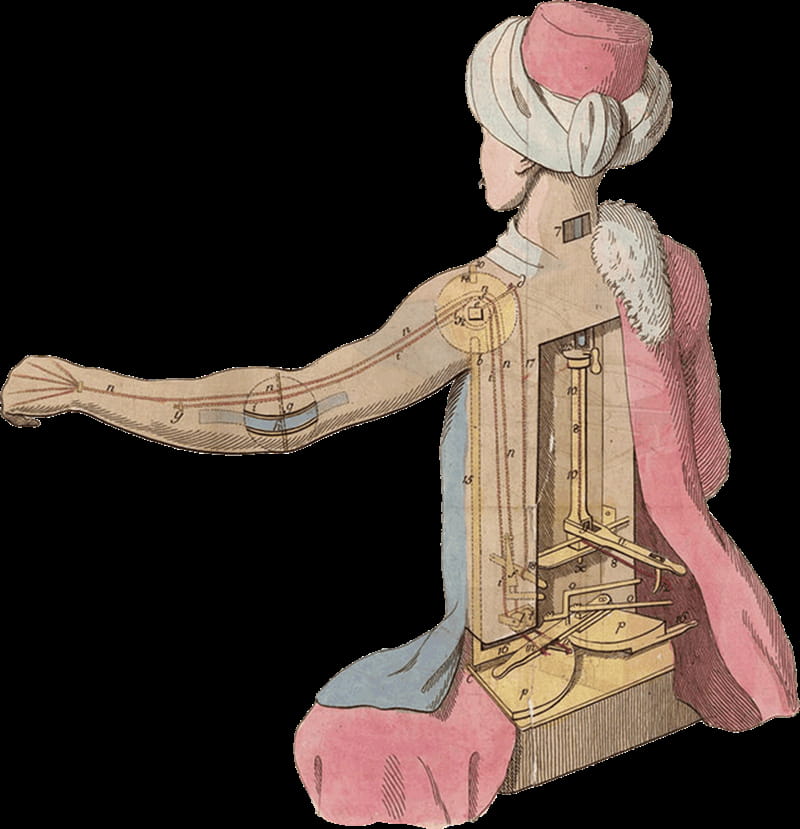

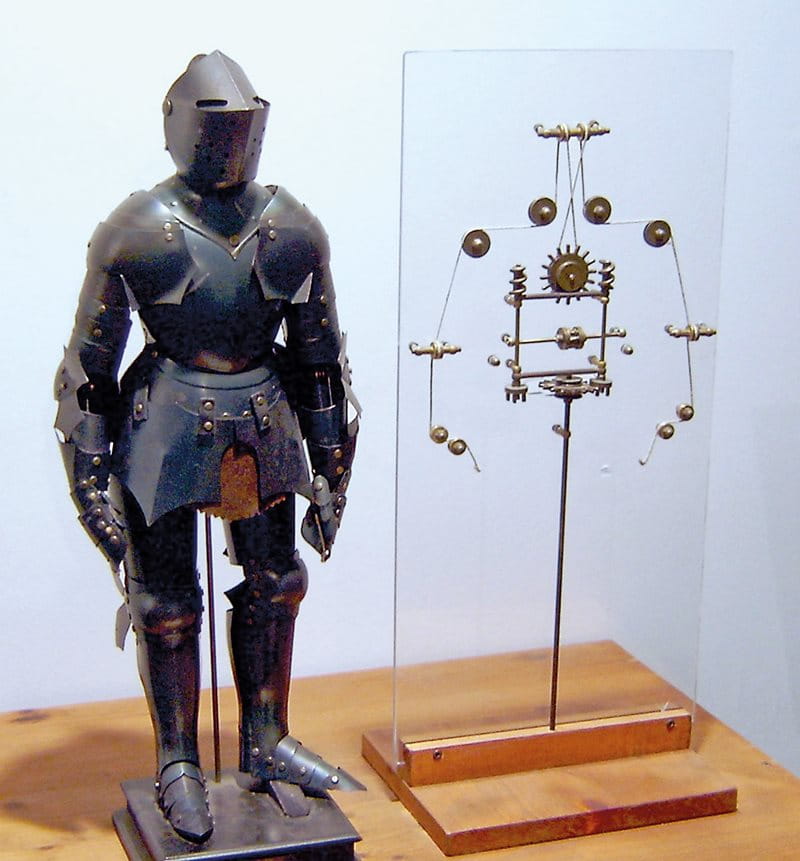

Al-Jazari’s influence among European Renaissance scientists was particularly visible in the work of da Vinci, who was fascinated by mechanisms of the human body and investigated ways of simulating actions of living beings. In 1495, he built a humanoid robot with pulleys and gears allowing it to move its arms and jaw, and to sit up and stand. The automaton, dressed as a knight in bulky German Italian armor, could also lift its visor, revealing its face and its moving jaw. Da Vinci’s robot employed a four-factor mechanical operating system integrated in its upper torso, and a separate three-factor system in the legs. It made its public debut at a gala event hosted by da Vinci’s patron, Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan.

Mark Rosheim, a us roboticist whose company develops robotic systems for nasa, built a working version of da Vinci’s automated knight in 2002 using da Vinci’s own drawings.

Rosheim says he was inspired in his youth by da Vinci. He developed a robotic serving cart from da Vinci’s sketches, which moved in programmable directions thanks to internal wooden cams. During a video interview in 2011, Rosheim revealed the workings of the cart in his company lab. Its intricate gears and cams not only served to transport viewers back to the 15th century, but also, for those familiar with al-Jazari’s influence on da Vinci, carried them even further back to the crucial Golden Age of Islamic science and engineering.

It was a tangible example of not only how far we have come, but also of how far back we go, to where the unexpected richness of our past seeds the unimaginable potential of our future.

You may also be interested in...

History in Objects: 12th-Century Glass Flask an Islamic Golden Age Masterpiece

History

Arts

Golden Vessel From the Islamic Golden Age Reflects Cross-cultural Connections

The American Hands Weaving Legacies From Saffron Threads

Science & Nature

Meet the keepers of US-grown saffron—a spice prized around the world—who have cultivated it as a culturally important ingredient for generations.

Voices That Shape Cross-Cultural Understanding

History

In its 75-year history, AramcoWorld has enlightened readers with stories about people throughout history and the modern world who have made an impact. Part 5 of our anniversary series examines the magazine’s positive portrayals of explorers, teachers, scientists and others to fulfill a mission of cultural bridge-building.