Morocco's Cinema City

From Lawrence of Arabia in the ‘60s to Star Wars in the ‘70s to Game of Thrones last year, Ouarzazate is where it’s at for film and TV shoots— more than 100 a year—and it’s home to North Africa’s newest film festival.

“Walk past ancient Egypt and then turn left at Tibet,” says Amine Tazi, general manager of Africa’s largest film and studio complex. “That’s where we filmed the Saudi tv series Omar,” about the second caliph of Islam, Omar ibn al-Khattab.

If the desert film sets look even vaguely familiar to a visitor, he explains, that’s because they probably are: Recently they were also backdrops for, among other things, episodes of the us television hits Homeland and Game of Thrones. But Omar took a full six months of shooting to produce 30 episodes, in Arabic. That was solid business for the two studios Tazi manages, Atlas and CLA, which were, until this year, solely responsible for making the town of Ouarzazate, poised between the Sahara desert and the Atlas Mountains in eastern Morocco, into a continental capital of cinema.

“Omar reused an existing film set to look like Damascus,” recalls Tazi, a no-nonsense studio boss whose role model for dealing with production challenges is a bulldozer. “Then we built [a replica of] the holy Ka‘bah in the desert next door.” He notes he holds a government license that allows him to draft in the Moroccan army as extras: For Kingdom of Heaven, in 2005 Tazi equipped 3,000 real Moroccan soldiers with spears and sandals so they could fight a running battle scene across an imaginary Palestine. “Our studios are known as ‘Ouallywood,’” he quips. “Hollywood, Bollywood, they all come to us to film.”

A faux-Pharaonic entrance sets the tone for cla Studios, which, with its partner Atlas, offers interior and exterior film sets that can take filmmakers from ancient Egypt to fairytale kingdoms—and almost anywhere in between. Used for countless Arab film and television productions since its founding in 1983, it has also hosted world-famous directors such as Martin Scorsese, Ridley Scott and Oliver Stone.

It’s a testament to its unique topography that the cinema industry in Ouarzazate (pr. Wahr-za-zaht) predates Tazi’s studios. Clear mountain air funnels down from the High Atlas to the north. It rarely clouds over, let alone rains. In 1962 British producer-director David Lean became the first top producer to utilize the site’s crystal-clear atmosphere when he shot shimmering desert scenes for Lawrence of Arabia. Those same dunes, casbahs and mountain lakes now stand in for Saudi Arabia’s Empty Quarter, rural Afghanistan, the Russian steppe and more.

Morocco’s human diversity also helps. If a movie needs African actors, local casting directors tap a regional database of on-call extras in towns like Erfoud, near the Algerian border. For Mediterranean types, they phone contacts in Tangier to the north. In 1997 American director Martin Scorsese planned to fly 400 ethnic Tibetans to Ouarzazate for his Dalai Lama epic Kundun, but local fixers visited a Berber tribe whose ancestors fought for France in Vietnam and, as a result, married and brought home dozens of Indochinese women. Scorsese placed their Asian-looking offspring to the rear of his set pieces, with a mere 60 bona fide Tibetans front-of-shot.

It’s clear that both the region and the movie industry enjoy a largely symbiotic relationship, but it’s precarious, explains Tazi. If the moviemakers succeed, Ouarzazate will maintain the current windfall that now is financing a new wave of Moroccan and Arab actors and directors. If they don’t, the town risks a return to its status as an obscure, if picturesque, dusty crossroads between the Atlantic and Timbuktu.

“Fortunately, the wealth our blockbusters bring is transferable to the town,” says Tazi. By way of example, when a production is shot wholly within Morocco, around 30 percent of the budget is spent locally on everything from hotels and meals to helicopters. That’s a huge boon for a city nudging 100,000, especially when one considers that Kingdom of Heaven had a budget of $130 million. More recently, in 2014, when nbc’s marathon A.D. The Bible Continues checked into Ouarzazate, it employed some 600 local artisans for half a year.

Outside the walls of Tazi’s adjacent studios, ironworkers are hammering out swords and shields that will be laid down only after filming. Street seamstresses sew tunics and togas in the warm Saharan air. My driver tells me he regularly doubles as an extra for $25 a day plus lunch. My barber, it turns out, moonlights as a hair-and-makeup man, a profession in the $50-per-day category. The semi-desert that surrounds Ouarzazate may not have resources like oil or gas, “just excellent natural and human resources,” concludes Tazi.

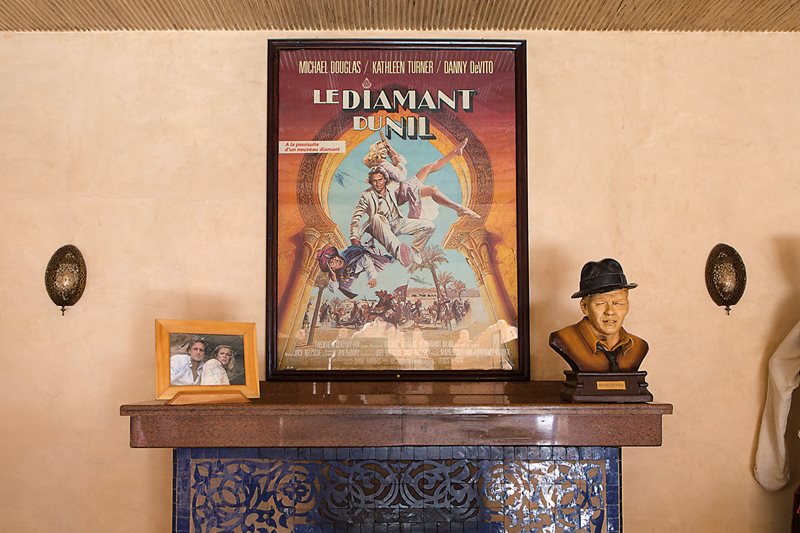

As the movie industry matures, those resources are more and more tapped. Entrepreneur Mohamed Belghmi, who first saw a need for a permanent movie-production space in 1983, built Atlas Studios. When the Michael Douglas adventure The Jewel of the Nile was shot here two years later, 20th Century Fox flew out the camera crew, assistants, grips, animal handlers and even caterers. Now those slots are usually filled by graduates of film-technician courses at the École de Cinéma de Ouarzazate and production and scriptwriting classes at the Faculté Polydisciplinaire. All that’s needed now to make a foreign movie is to fly in a director and a bag of cash. According to studio bosses, about 80 percent of movie staff are now Moroccan.

These figures are confirmed by Mohamed El Hajaoui, a dashing 27-year-old actor who also leads tours of the Atlas and CLA Studios. (The latter was created in 2004 as a partnership among Italian studio Cinecittà, the late producer Dino de Laurentiis and Moroccan investor Saïd Alj, and both studios are now co-owned.)

The studios, it seems, can fabricate anything anywhere—a virtual planet of plaster, plastic and polystyrene held together with bits and strips of wood and metal. With a few deft moves, the squad can transform the Luxor set into Constantinople, Jerusalem, Makkah or Persepolis. It’s here that young assistant directors like Mehdi Elkhaoudy learned the trade shooting scenes on the us television series Prison Break, which turned a real local primary school into a temporary Yemeni jail set, and the recent Ben Kingsley series Tut, in which El Hajaoui played a small role. The actor demonstrates the set’s resilience by picking a giant foam “rock” off a medieval catapult and hurling it against a plywood “citadel wall,” which holds fast.

A boom-mounted camera stretches over film-crew members, actors, cameras, tents and gear at CLA Studios during the filming of episodes in the hbo series Game of Thrones, one of about 100 international television episodes and 20 feature films that annually come to the area.

El Hajaoui and I walk into a plaster-built mock village that provided the backdrop for scenes in Gladiator (2000), yet another Hollywood epic attracted to Ouarzazate by its combination of ethereal light and down-to-earth costs. (That film, he points out, is one of four veteran British director Ridley Scott shot here.) As he shows me around, we meet Arab and European movie tourists. Sauntering over the sets, playfully emulating cinematic heroes, they are also a source of income to the town and, more generally, Morocco. Ouarzazate’s hotels reported a 40 percent gain early this year over last year, and over the past 10 years, national foreign-visitor totals have risen from around 7 million to more than 10 million a year.

The props departments at both studios appear to be working overtime. Among the upcoming films is an Indian historical epic, for which staff are polishing Saracen swords, Phrygian standards and Roman shields that had their origin in some earlier production. Behind them, gathering dust in a hanger-like storeroom the length of two buses is a wonderland flea market full of abacuses, leather moneybags, brass bowls, scrolls and knick-knacks from pretty much any century you wish for. The nearby costume department, meanwhile, is busy dyeing garments for an American-boy-meets-Arabian-girl desert drama.

The whinny of horses eager for their midday meal leads us to the animal training center, where 17 staff care for two dozen camels and donkeys, indispensable creatures for any desert tale. Horse trainer Brahim Rahou leads us to a handsome albino stallion named Spirit, who is the stable’s most recent celebrity. “This horse carried Khaleesi,” Rahou explains, referring to the nickname for the lead role of Daenerys Targaryen in Game of Thrones, which shot some five episodes here.

In sum, the Ouarzazate studios and region annually attract around 10 foreign and 10 Moroccan feature movie productions, plus 100 or so predominantly international television episodes—a number that has been rising, as the series format has gained traction on outlets such as Netflix and Amazon. Nationally produced films, such as Les Indigènes (2006), a drama about Moroccan soldiers who fought for France in World War ii, are intensely popular, in most years attracting as much as a third of Moroccan cinema visits and making up half of the country’s top 10 biggest-grossing films. What the likes of actor El Hajaoui and animal trainer Rahou require is a sustained throughput of hits. These days, although work is going well, runs the sentiment on the ground, everyone is always eager for more.

It’s fortunate that the job of attracting foreign movies here has fallen to Abderrazzak Zitouny, the whirlwind director of the Ouarzazate Film Commission. Since 2008 he has pulled in several million-dollar productions by force of personality alone. A few years ago, “Werner Herzog came to our Ouarzazate stand at the Los Angeles Film Festival,” remembers Zitouny, a swashbuckling dead ringer for a Moroccan Johnny Depp. “I sold our region’s beauty like I was selling a dream.” He sold it so well that the famous German director offered him an acting job, Zitouny says. “I said, ‘Of course, Werner, but only if you film in Ouarzazate!’” The result was Queen of the Desert, a 2015 biodrama about British writer and policymaker Gertrude Bell.

Initial filming enquiries land in Zitouny’s downtown office near the École du Cinéma. As the second-oldest movie authority on the continent after South Africa, the Ouarzazate Film Commission has clout. A foreign producer or location manager is usually looking for an idea of local dunes, mountains or medieval-looking villages, professional photos of which Zitouny keeps on his hard drive. A database of every carpenter, caterer and grip in southern Morocco is expected to be completed this year. “That way we can prove that we can offer blockbuster movies and tv shows everything,” he says.

When a production assistant arrives in Zitouny’s office, he or she is driven about 30 kilometers northwest of town to the hill village of Aït Benhaddou. If the producer is American, Zitouny shows off its unesco-protected kasbah where Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (2010) was filmed. With Arab guests, he expounds upon The Message (1976) by legendary Syrian director Moustapha Akkad, an Oscar-nominated exodus-to-Madinah epic shot in the same mountain outpost.

“The movie business is a hard-nosed one,” Zitouny says, admitting that the line between making a film in one place and not in another rests heavily on the bottom line. The commission can smooth the way, from import procedures for camera equipment to discounted entrance fees to local sights and much in between. However, the most enduring allure is Morocco’s value-added-tax (vat) exemption on all supplies and services, which knocks roughly 20 percent off the top for starters. “Combined with low costs for hotels, drivers and extras, we can make a movie for 50 percent less than in the United States or Europe,” Zitouny says. In addition, he says, a single permission grants filming rights anywhere in the country. “Try doing that in Paris or Dubai,” he says with a smile.

The incentives are paying off. The daily flight from Ouarzazate’s tiny airstrip to Casablanca on the coast, which connects with Royal Air Maroc’s direct New York flight, is welcoming stars. This year the downtown Musée du Cinéma, a nearly endless exhibition of movie props that opened in 2007, will inaugurate two screening rooms for local viewing of locally made feature films as well as screening of pre-production rushes before hopping back into the desert for final shots.

Zitouny led a recent presentation to Morocco’s movie-loving King Mohammed vi, which helped win support for a forthcoming, additional tax rebate on foreign film productions. Even with that, it is an intensely competitive industry: Can Ouarzazate attract the globalized, digitized moviemakers of tomorrow? And locally, can its film industry ensure that all get a piece of the big-budget pie?

The young man who has saddled himself with those two tasks is another film-fanatic livewire. Abdelali Idrissi is co-founder of the brand-new Ouarzazate International Film Festival. The 37-year-old prop master and art director produced an acclaimed short film program on a shoestring budget for its debut in April 2016. With a passion for inclusivity, Idrissi even screened movies in the local prison. We meet in Ouarzazate’s Taourirt Kasbah, where parts of the original 1977 Star Wars were filmed.

Abderrazzak Zitouny, director of the Ouarzazate Film Commission, takes a center-stage throne on a movie set at the Ouarzazate Cinema Museum. The commission is the second-oldest on the continent after one in South Africa, and it has reeled in several million-dollar productions since it opened in 2008.

“It’s great that we welcome Ridley Scott and Martin Scorsese,” explains Idrissi. “But our industry needs a relationship with the set builders and costume workers who don’t always have the technology to watch the movies that they helped to make. Essentially, we are a cinema city without any cinemas.” By screening 100 video shorts on pop-up screens around town—10 of them filmed in Ouarzazate or wider Morocco—the festival drew crowds of up to 1,000 to see their city on the silver screen, many for the first time.

Idrissi co-launched the festival with high hopes and basic tools. “We used Facebook, Google Plus and film contacts to spread the message,” he says. Word went viral and some 3,000 entries flooded in from countries as diverse as Indonesia, Pakistan, Colombia and Nigeria, as well as the us (which topped the list with 406 entries).

“We were surprised,” Idrissi says with a laugh. ”Then we realized we were obliged to watch every single short film!” To handle the volume, organizers expanded the film-selection committee to include Idrissi’s brother Abdessamad, who works in film production in Berlin, and his German colleague Stefan Godskesen. Although the festival is “for all ideologies,” the committee checked each cinematic short for culturally offensive content, whittling down the entry list to 100, set screening dates and booked some 15 directors to attend. Just one ingredient was missing: cash.

“We needed money for screening equipment, sound systems and even meals,” says Idrissi as he strides around the ramparts of Kasbah Taourirt. He presented his festival budget to Atlas Studios and the film commission, but there were no takers. A last-minute donation from a Saudi solar energy developer and operator, acwa Power, paid for the stages and rigs that were scheduled to be erected the very next day. Idrissi and his colleagues plugged the event’s remaining budget holes from their own pockets.

“It’s fair to say that we lost several kilos in weight during the six days of screening,” he explains. Just 200 people came to the opening-night screening of Wintry Spring, a short film about an Egyptian girl entering womanhood. There were more viewers on day two when a member of the film commission dropped in on the Iraqi documentary Dyab, about a Kurdish Yazidi boy who wants to become a filmmaker. By day three the screening in Ouarzazate jail (“The prisoners told us to come back next year!” Idrissi says) boosted viewer numbers into four figures. Then the film commission stepped in with a small donation, too.

After an early start the following day, the jury lugged rented equipment to the film-set village of Aït Benhaddou. Among the audiences were 220 schoolchildren, many of whom had seen Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie filming in their kasbah but had never watched a movie set in their hometown. They were “very happy to assist” in critiquing the animation section, Idrissi says.

About 30 kilometers west of Ouarzazate, the hillside mudbrick village of Aït Benhaddou is both a unesco World Heritage Site and a popular set for many films, including The Jewel of the Nile, Gladiator and more.

In all, the festival logged 5,000 viewers, nearly half under age 25. “Of course, many people who could not travel to the Moroccan desert were watching some of the short films on YouTube and thinking about Ouarzazate,” says Idrissi.

The make-up of the event’s real-life audience was critically important to Idissi’s aims. Pupils from the École de Cinéma and the Film Faculté got to witness the latest filmmaking techniques while gleaning tips from the directors who had flown in from abroad. More importantly, attendees took a tour of the sets and digital facilities at Atlas and CLA Studios. “In 10 years’ time, these short-film guys might be top directors or producers,” notes Idrissi. For the 2017 edition of the festival, featuring technical and artistic workshops in both city academies, he is aiming to accommodate 50 visiting directors when the event turns on its projectors in September.

It’s all a distant cry from the very first movie ever shot in Morocco. Back in 1897, France’s Lumière brothers captured flickering images of a goatherd, a sequence that would now seem quaintly stereotypical. Now a new generation of Moroccan filmmakers are opening studios where they aim to beat the cinematographers from the West at their own game.

In April producer Khadija Alami opened Oasis Studios Morocco near Oasis du Fint, 15 kilometers from downtown Ouarzazate. Location, producer and equipment are all A-list. It was this oasis that backdropped in Lawrence of Arabia and Prince of Persia, and Alami’s credits include Homeland and Captain Phillips (2013). “There is so much demand for Hollywood and Arabian movies it warranted opening our studio,” says Alami, whose new one-stop shop will rival incumbents Atlas and CLA. For the first time, foreign television productions can be scripted, shot, edited and delivered without leaving the compound and using a crew entirely Moroccan.

Alami’s Hollywood-standard studios exceed anything on offer in Morocco’s more traditional rivals, as well as anything in Jordan or Tunisia. Only the production powerhouses of Turkey and Egypt produce more Middle East-related films. “Political stability means that Morocco’s relative safety is a huge asset for foreign pictures,” Alami explains. However, she adds that even beyond this lies what has always been top currency in movies: Beauty. “It is Ouarzazate’s film-set looks that keep producers coming back for more.”

About the Author

Rebecca Marshall

Rebecca Marshall is a British editorial photographer based in the south of France. A core member of German photo agency Laif and Global Assignment by Getty Images, she is commissioned regularly by the New York Times, Sunday Times Magazine, Stern and Der Spiegel

Tristan Rutherford

Tristan Rutherford is a 7-time award-winning journalist. His writing appears in The Sunday Times and the Atlantic.

You may also be interested in...

From Sultan’s Kitchen to Delhi’s Streets: Ni‘matnāma Lives On

Food

A sultan’s 500-year-old cookbook still ripples across South Asia, from kitchens to street stalls to celebratory tables, preserving centuries of technique and taste.

Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

Arts

Culture

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.

Author Giulia Paoletti Traces History of Senegal’s Photography

Art historian Giulia Paoletti discusses her book Portrait and Place, exploring the rich but largely undiscovered history of photography and portraiture in Senegal.