Egyptology’s Pioneering Giant

Circus strongman, amateur engineer, locator and excavator of tombs and temples, mover of massive masterpieces—to England—Giovanni Battista Belzoni left a legacy in Egyptology that was, in every conceivable way, large.

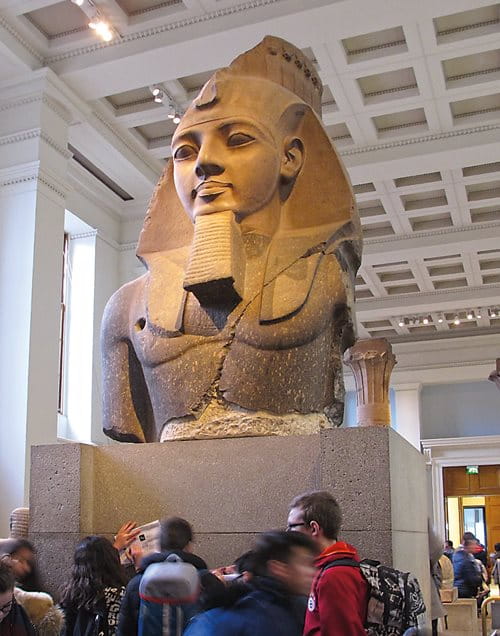

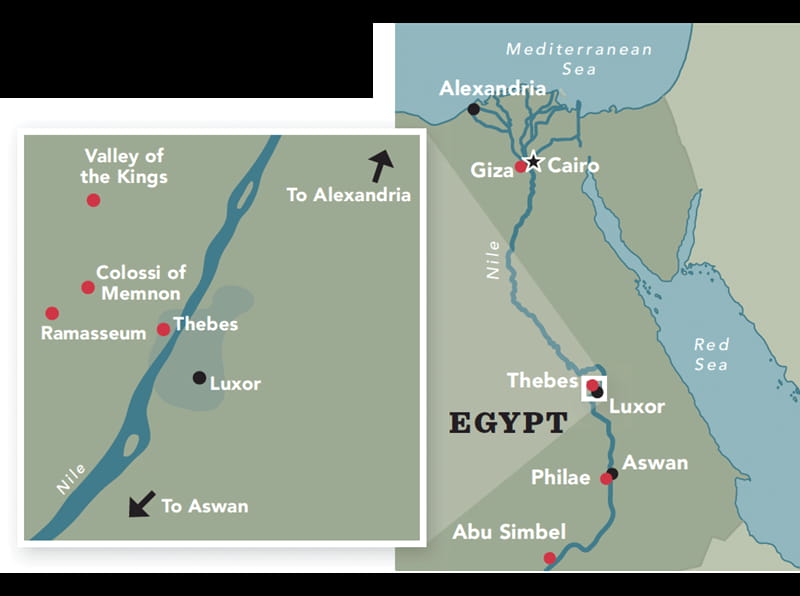

Weighing 3.6 metric tons and measuring nearly three meters from chest to crown, the 3,200-year-old red-granite bust of Pharaoh Ramses ii fairly lords over the British Museum’s Egyptian sculpture gallery. Napoleon’s troops had tried, yet failed to so much as to budge the toppled, fragmented figure from its sandy resting spot in the Ramesseum, the pharaoh’s vast mortuary temple in Thebes, on the west bank of the Nile near present-day Luxor. But the pharaoh’s dead weight proved no match for the ingenuity of two-meter-tall showman, explorer, adventurer and engineer Giovanni Battista Belzoni.

Was Belzoni a desecrator and plunderer of Egypt’s pharaonic treasures, or just an Italian bull in an ancient Egyptian sculpture shop who, by his own account, clumsily crushed moldering mummies to dust? Or was he a serious, early archeologist, meticulous by the measure of a time when his profession didn’t even have a name, let alone international standards? To find out, I turned to Belzoni’s own record, Narrative of the Operations and Recent Discoveries within the Pyramids, Temples, Tombs, and Excavations in Egypt and Nubia, published in 1820. But I quickly learned that his story in Egypt really began nearly two decades earlier in London, on the stage of the Sadler’s Wells Theatre, a brisk half-hour walk northeast of the British Museum.

Belzoni had arrived in London earlier that year by way of Amsterdam and Paris, where he had been knocking around on a meager income peddling religious relics, with occasional subsidies from his family back in Italy. Born in Padua in 1778 (or 1783, the date is uncertain) and the son of a barber, he picked up informal skills in mechanics and hydraulics, possibly by working on Rome’s famed fountains.

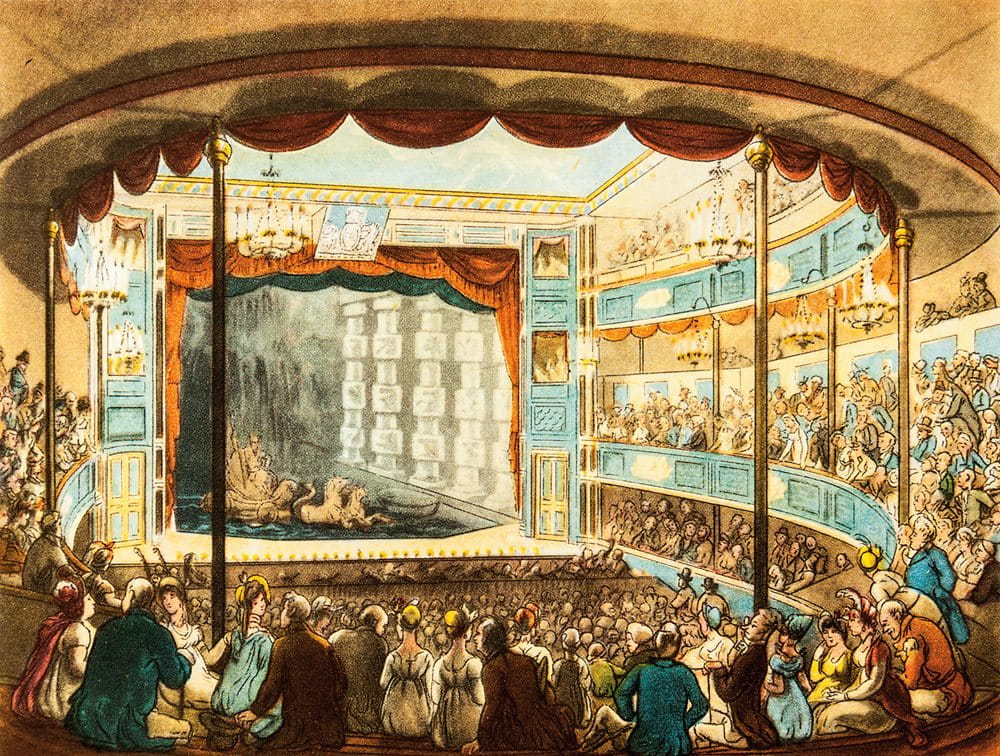

At Sadler’s Wells, Belzoni developed his signature act, the “Human Pyramid.” Dressed in a circus-strongman outfit and—if the illustrations are to be believed—bearing a colorful flag in each hand, Belzoni strutted the stage with a 58-kilogram iron frame suspended from his shoulders, upon which were arrayed a full dozen members of the theater company. The sensational act launched his career as “The Great Belzoni,” and he won fame across Europe.

Over the next decade, Belzoni tweaked his performance with stagecraft involving waterfalls, weights, levers, rollers and balancing techniques. Along the way, he married an Englishwoman, Sarah Bane.

In 1815 the Belzonis were en route to Constantinople (now Istanbul), when they chanced to meet an agent of the pasha of Egypt who piqued their interest with an offer to travel to Cairo and devise a “hydraulic machine, to irrigate the fields.” Belzoni welcomed the offer to be taken seriously as an engineer, not just a giant. He accepted the terms offered and they set sail for Alexandria on May 19, 1815.

They settled in Bulaq, Cairo’s rough-and-tumble port. Belzoni indeed developed an irrigation device, a water-bearing “crane with a walking wheel,” which demonstrated it could draw far more water than the traditional saqiya water wheel. Yet it met with skepticism and worse. In its working debut before the pasha and his ministers, an accident injured one of the workers operating the device. The ministers declared it “a bad omen,” and the pasha consigned Belzoni’s waterwheel to oblivion.

But Egypt had more in store for him.

One of most coveted prizes was the exquisitely carved bust of Ramses ii.

The top half of a once-full-length seated figure, it lay half-buried in a courtyard of the pharoah’s 13th-century-bce funerary temple, long known as the Memnomium because of its proximity to the two 18-meter statues of Amenhotep iii known as the Colossi of Memnon. Salt welcomed the opportunity to engage Belzoni “for the purpose of raising the head of the statue of the younger Memnon, and carrying it down the Nile.” He drew up an agreement on June 28, 1816.

Arriving at Thebes, arguably the world’s greatest open-air museum, on July 22, Belzoni, like most, was awestruck by its temples, mostly built during the height of New Kingdom’s architectural and artistic glory, from the 16th to the 11th centuries bce. “It appeared to me like entering a city of giants, who, after a long conflict, were all destroyed, leaving the ruins of their various temples as the only proofs of their former existence,” he recorded.

After examining the ponderous relic, Belzoni made a simple plan: Employing his circus-proven, weight-levering know-how, he would hoist the statue onto a cart built from poles, drag it by rope over rollers to the Nile and load it onto a boat.

Five days later, on July 27, Belzoni and a crew levered the statue onto the cart. While dragging it through the temple’s entrance, Belzoni noted they had to “break the bases of two columns”—an act sure to horrify modern archeologists.

“He was not a true Egyptologist or archeologist in the modern sense, but what he did was still remarkable,” says Mostafa Al-Saghir, director general of Karnak Antiquities. A native-born Egyptologist, Al-Saghir ranks Belzoni among the many plunderers of his country’s heritage. Yet he recognizes that the Italian giant had a unique instinct for excavation that set him apart from others who followed.

“The way that Belzoni lifted the small colossus of Memnon [the head of Ramses] from the Ramesseum was the same technique used by the ancient Egyptians,” Al-Saghir points out.

And thus, on August 12, 1816, “the young Memnon arrived on the bank of the Nile.”

Arriving at Thebes, Belzoni wrote: “It appeared to me like entering a city of giants, who, after a long conflict, were all destroyed.”

While awaiting a boat capable of bearing such a cargo down to Alexandria, Belzoni took a trip farther south up the Nile—as did I.

One of Belzoni’s most eagerly anticipated destinations was the island of Philae. Reputed burial place of Osiris, Egyptian god of the afterlife, it is one of the most poetic settings in all of Egypt. Verdant and palm-fringed, it was located, in Belzoni’s day, in the middle of the Nile at Aswan. (When the Aswan High Dam’s Lake Nasser threatened to submerge the island in the 1970s, unesco engineers moved Philae’s entire temple complex to higher ground at neighboring Agilkia Island—a feat that no doubt would have impressed Belzoni.)

Belzoni crossed to Philae just before dawn, standing “at the stern, waiting for the light to unveil that godly sight.” Wandering the island, he noted what he might haul away on a later trip: Top prizes included a fine frieze depicting Osiris as well as “an obelisk of granite about twenty-two feet [6.5 meters] in length and two in breadth” that stood at the entrance to the second pylon or gate, to the Temple of Isis. Today, thanks to Belzoni, only its base remains at Philae, and the obelisk stands in the gardens of Kingston Lacy, a National Trust property in Dorset, England. Its eventual journey there would come close to being Belzoni’s most disastrous enterprise.

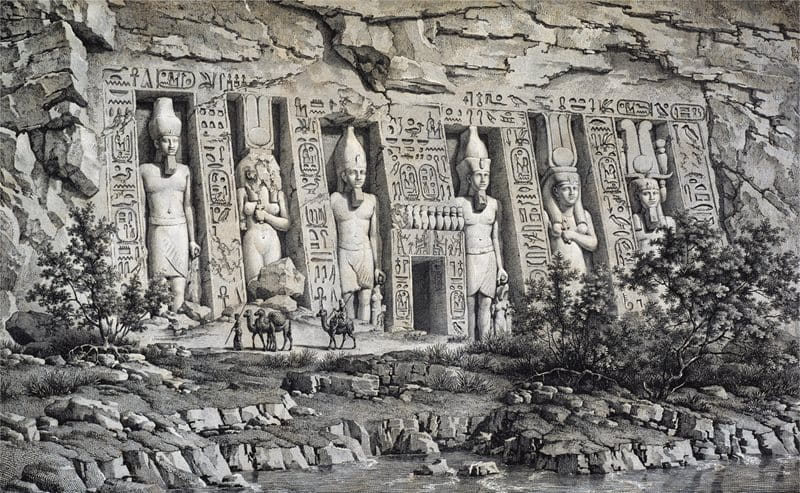

Belzoni continued upstream with his party toward the temple of Abu Simbel, some 500 kilometers south of Luxor, to investigate the remains of four 20-meter seated statues of Ramses the Great. They found the temple’s grand entryway drowned in sand, and Belzoni realized that excavating there would be like “making a hole in water … an endless task.” Unless, that is, he could find a way to keep the sand from refilling the hole after every scoop.

With palm logs and locally hired labor, Belzoni drove a palisade into the sand in front of the temple. Then he wet the sand “close to the wall over the door” to stop the drifts from sifting back down into the hole. After exposing the face and shoulders of one statue, he had to interrupt the task to return to Luxor to load the bust of the Ramses statue onto a boat. He arranged for a local tribal leader to safeguard the site, sketched his progress and left “with a firm resolution of returning to accomplish its opening.”

Back at Luxor, Belzoni hired a boat heading upriver to Aswan for its return journey to Cairo. It would first collect the pieces of the Osiris frieze from Philae and then pick up the Ramses head at Luxor. The obelisk at Philae, however, would await a longer vessel.

In the meantime, Belzoni literally began poking around the Valley of the Kings. “[I]n one of most remote spots [I] saw a heap of stones, which appeared to me detached from the mass,” he wrote.

“The vacancies between these stones were filled up with sand and rubbish. I happened to have a stick with me, and on thrusting it into the holes among the stones, I found it penetrate very deep.”

He detected telltale flood patterns and noted accumulated debris that might be hiding tomb entrances. Sure enough: “On removing a few stones, we perceived, that the sand ran inwards.” Within two hours he and his crew cleared away the entrance to what turned out to be the 14th-century-bce tomb of Ay, Tutankhamun’s successor, a site now designated kv23, which stands for Kings Valley tomb number 23.

Drovetti’s men, it turned out, had furthermore convinced the boat’s captain that the Osiris frieze stones would sink his boat, and that transporting the Ramses sculpture would do likewise. The regional governor then came to Belzoni’s rescue: He ordered the captain to transport the bust of Ramses and anything else Belzoni wanted. Belzoni and his crew eased the giant head down a specially built ramp and onto the vessel, which didn’t sink. On November 21, 1816, Belzoni accompanied the head to Alexandria, where it would await transport to England.

Archeologist Don Ryan of Pacific Lutheran University leads me down a rocky escarpment in the Valley of the Kings to kv21, a tomb that both he and Belzoni have excavated. Ryan has written and lectured internationally on Belzoni, and he rejects his predecessor’s reputation as a ham-fisted plunderer, crediting him rather as the valley’s first modern excavator.

“He is too easy a target. There were no rules back then, no systematic archeological practices. That wouldn’t happen for another 70 years. So you have to look at Belzoni in the cultural context of the times,” he says.

Equally resolute in defending Belzoni, American University of Cairo Egyptologist Salima Ikram is willing to forgive Belzoni’s clumsiness, a sin even modern archeologists occasionally commit.

“Who among us hasn’t had their Belzoni moment?” she asks.

Still, one winces to read some of Belzoni’s accounts. Particularly painful reading is his quest for papyri, made by literally crawling over stacks of mummies at Qurna, near the Ramesseum: “[W]hen my weight bore down on the body of an Egyptian, it crushed it like a band-box … so that I sunk altogether among the broken mummies, with a crash of bones, rags and wooden cases, which raised such a dust as kept me motionless for a quarter of an hour, waiting till it subsided,” he wrote. The pulverized mummies, he concluded, “were rather unpleasant to swallow.”

In February 1817, at Salt’s behest, Belzoni returned to the Valley of the Kings, accompanied this time by Salt’s secretary and an artist. Their mission was to find more artifacts, including mummies and papyri; for his own part, Belzoni was eager to return to his interrupted excavation at Abu Simbel.

It wasn’t until summer that Belzoni got his wish, and he and his crew excavated the front of the temple in temperatures topping 51 degrees Celsius. On July 31 they reached “the upper part of the door as evening approached [and] dug away enough sand to be able to enter,” he wrote. But Belzoni chose to wait until dawn, after he observed that the rising sun would pierce directly into the temple’s massive, east-facing doorway.

As the first light for more than a thousand years illuminated the interior, the team “entered the finest and … most magnificent of temples … enriched with beautiful intaglios, painting, colossal figures,” Belzoni gushed.

The dust of the pulverized mummies below him was, he concluded, “rather unpleasant to swallow.”

Belzoni’s superlatives still ring true today, I thought as I wandered in my own awe through the lofty, pillared entry hall lined by eight facing statues of Ramses taking the form of Osiris. Although Belzoni and his team took little from the temple, they spent several days measuring, drawing and compiling a detailed record of the structure’s interior and exterior.

“Taking measurements, drawing pictures—that is real archeological documentation,” says Ryan, who often refers to Belzoni as a “proto-archeologist.” The accuracy of Belzoni’s record-keeping, says Ryan, remains useful to this day.

Greek writer Herodotus and Roman writer Strabo, respectively from the fourth century bce and first century ce, recorded estimates of as many as 47 royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings, though only 18, Strabo said, were visible. The French had identified 12.

Belzoni was aware of the ancient reports and, like others, took them as reason to keep looking. Back near the tomb of Ay, using “a large pole … not unlike a battering ram,” he crashed his way into a tomb with eight mummy cases, including one draped in painted linen, “exactly like the pall upon the coffins of the present day.” It disintegrated on touch. Because Belzoni’s entrance destroyed the clay seals that would have named the interred, what are now known as the kv25 mummies remain unidentified.

On October 9, 1817, after just three days of digging, Belzoni discovered both kv21 and the 12th-century-bce tomb of Montuherkhopshef, eldest son of Ramses ix. The murals, which Belzoni described as being in a “perfect” state of preservation in the tomb’s entry corridor, show the prince making offerings to various gods.

Two days later, Belzoni disturbed the sleeping chamber of Ramses i (1292 to 1189 bce), the founding father of Egypt’s 19th Dynasty. The pharaoh, however, had long since been moved by 21st-Dynasty priests for safekeeping and only his ka—a statue serving as the soul’s resting place—stood “six feet six inches [two meters] high, and beautifully cut out of sycamore-wood.” Alongside it lay a red-granite sarcophagus containing two mummies, neither of them pharaohs.

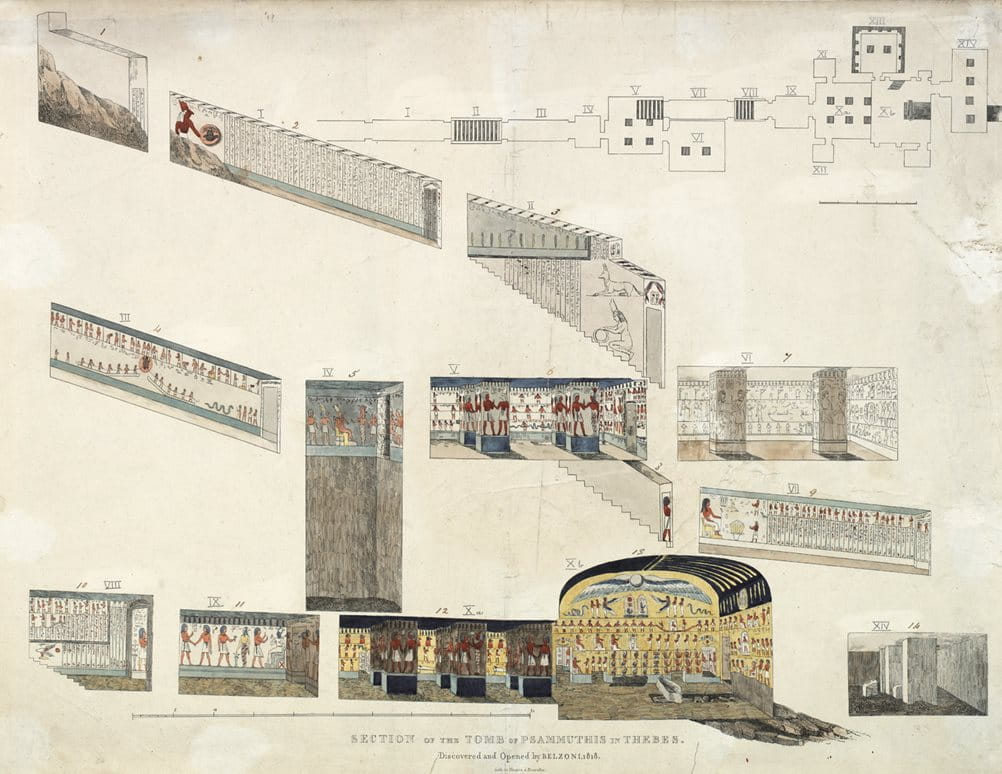

The discoveries continued: October 16 was, Belzoni noted, “a fortunate day, one of the best perhaps of my life.” Reading the terrain, he dug about 14 meters from the tomb of Ramses i, where he “had strong reason to suppose, that there was a tomb in that place.” Two days later he entered what remains the deepest, most magnificently decorated tomb in the Valley of the Kings: that of Seti i, successor to Ramses i.

“We perceived that the paintings became more perfect as we advanced farther into the interior,” Belzoni wrote of his descent, this one made gingerly, creeping along by candlelight through multiple chambers and along the tomb’s 137-meter-long central corridor. The vast frescoes depict scenes from the Book of the Gates, wherein the deceased pharaoh passes through a series of gates, guarded by deities, to reach the afterlife. The burial chamber’s vaulted, painted ceiling—an innovation, along with the floor-to-ceiling murals—features an inky-blue night sky with astronomical symbols and constellations.

Following Belzoni’s footsteps down, though today with better lighting, I was lucky to gain access to the tomb, which had only recently reopened after extensive conservation. The deeply saturated original colors have faded somewhat due to exposure and damage done by 19th-century archeologists (including Belzoni), whose wax impressions stripped off irreplaceable layers of paint.

The tomb’s unrivaled prize, however, lay in the crypt: an empty sarcophagus carved from a single block “of the finest oriental alabaster … minutely sculpted within and without with several hundred figures … as I suppose, the whole of the funeral procession and ceremonies relating to the deceased,” Belzoni wrote.

The Great Belzoni had increased the known number of tombs in the valley by half. However, much of the praise was bestowed on Salt, who assumed credit for the British discoveries in Egypt and who had been accumulating the fruits of Belzoni’s labor—statuary, papyri, mummies, etc.—to sell to the British Museum.

When Belzoni arrived with Sarah in Egypt in 1815, like most first-time visitors, one of the first things they did while in Cairo was to cross the Nile and venture to Giza, “to go see the wonder of the world, the pyramids.” And like many tourists of the day, he climbed to the top of the Great Pyramid for a sunrise breakfast before exploring its interior—where he got his massive frame stuck, briefly, in the descending corridor.

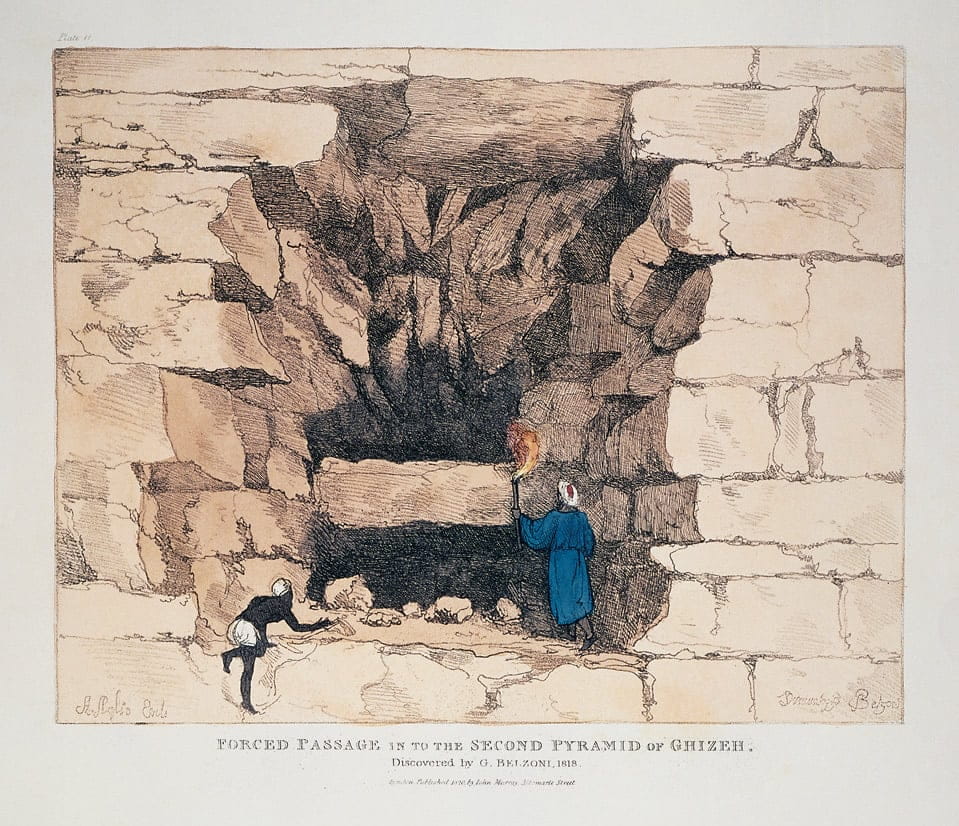

Now, nearly three years later, he was back, this time as an excavator, looking for a way to get into the Second Pyramid, also known as the Pyramid of Khafre, which writers up to that day had insisted had no entryway.

It was slow going at first. After a month of digging and a false passageway, they struck “a large block of granite, inclining downward at the same angle as the passage into the first pyramid, and pointing toward the centre.” Levering the stone out of the way, Belzoni found himself “in the way to the central chamber of one of the two great pyramids of Egypt.”

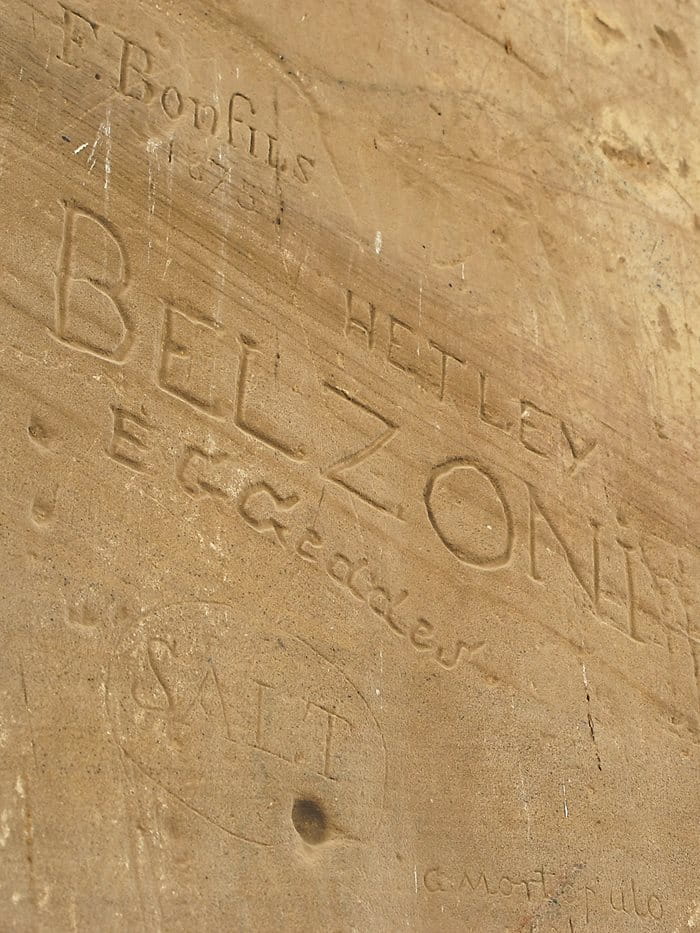

Although he became the first modern explorer to set foot inside its burial chamber, he was not the first since the pyramid’s construction: Arabic graffiti on the wall announced a visitor dating around 1200 ce. Following suit, Belzoni emblazoned his own name across the length of the tomb’s south wall, declaring: “Scoperta da [Discovered by] G. Belzoni. 2. Mar. 1818.”

Soon after this triumph, Belzoni faced yet another challenge from his French rivals. Belzoni learned that Drovetti’s agents had been assigned to Philae to preempt his removal of the obelisk. Belzoni made haste back to Philae, where he oversaw the loading of the obelisk—after dropping it into the Nile and, fortunately, recovering it.

That was, Belzoni decided, a dramatic swan song from which to exit Egypt’s vast stage. He and Sarah left for England in September 1819. He had discovered and excavated some of the most famous sites in ancient Egyptian history, yet both he and Sarah had endured illness, hardships, threats from the French and the perceived ingratitude of Salt who, ultimately, did publicly declare his high regard for Belzoni and arrange a generous stipend for him.

Nonetheless, Belzoni was ready to leave: “[N]ot that I disliked the country I was in ... nor do I complain of the Turks or Arabs in general, but of some Europeans who are in that country, whose conduct and mode of thinking are a disgrace to human nature.”

In March 1820 he published his narrative. Lavishly illustrated by the author himself, the book was a sensation, and the press warmed to him, hailing him as a “celebrated traveller” and “a pioneer … of antiquarian researches.” Cashing in on this wave of celebrity amid a general atmosphere of Egyptomania, Belzoni returned to the stage—this time in a spectacle that featured a scaled replica of the colorful tomb of Seti i in Piccadilly’s Egyptian Hall (coincidentally so named after its faux-Egyptian façade). True to his proven showmanship, Belzoni, assisted by a team of physicians, opened the evening’s entertainment by unwrapping a mummy.

The Piccadilly address is now an office building, though a photograph of the old performance hall hangs in the lobby. Crossing the street, I caught a double-decker bus to Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where Sir John Soane’s Museum stands along a quiet back street. Soane, a wealthy architect and avid collector of art and antiquities, purchased the Seti sarcophagus from Salt in 1824 for £2,000, after the British Museum declined it. (The museum had just spent a controversial £35,000 to buy the Elgin Marbles.) Soane placed the sarcophagus on display in the crypt-like basement of his trio of adjoining houses that now comprise the museum. It remains there today, protected by a glass display case.

In 1825 Soane debuted his acquisition, still the finest Egyptian artifact in the uk, by inviting the cream of London society to come see it. Taking a showman’s cue from Belzoni, Soane astonished his guests by darkening the room and setting candles inside the sarcophagus, whose glow proved visible through the translucent alabaster. On hand that evening was Sarah, but not her husband: It had been two years since The Great Belzoni had succumbed to dysentery during an expedition to West Africa.

Salt was not much luckier. Although he amassed a fortune auctioning off his pillage, he died in 1827 after trying to sell the bulk of his collection to the British Museum. Ironically, when it wouldn’t meet his asking price of £10,000, Charles x of France snapped it up, the better to enlarge the Egyptian collection at the Louvre.

Last year Soane’s museum began a commemoration of the 200th anniversary of Belzoni’s discovery of the Seti sarcophagus by opening an exhibit devoted to his life’s work. Belzoni, says curator Joanna Tinworth, did “the best he could at the time” with the tools at his disposal. While some scavengers, in the form of competing archeologists, left behind vacant tombs and rubble, Belzoni bequeathed to modern researchers detailed records that became one of the foundations upon which the modern science of archeology has been built.

You may also be interested in...

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

“Old Bridge” Story Inspires Lessons in Writing and Community History

History

Voices That Shape Cross-Cultural Understanding

History

In its 75-year history, AramcoWorld has enlightened readers with stories about people throughout history and the modern world who have made an impact. Part 5 of our anniversary series examines the magazine’s positive portrayals of explorers, teachers, scientists and others to fulfill a mission of cultural bridge-building.