The Art of Luxury: Metalwork in 12th-Century Seljuq Empire Courts

Opulent pieces found from some 700 years ago are now understood to be made of a common metal alloy that, in the 12th century CE, metalsmiths in the Turkic Seljuk dynasty transformed into luxury ware. Today, such pieces are as iconic of Islamic art as lavishly illustrated manuscripts or tilework tessellated with arabesques and geometry.

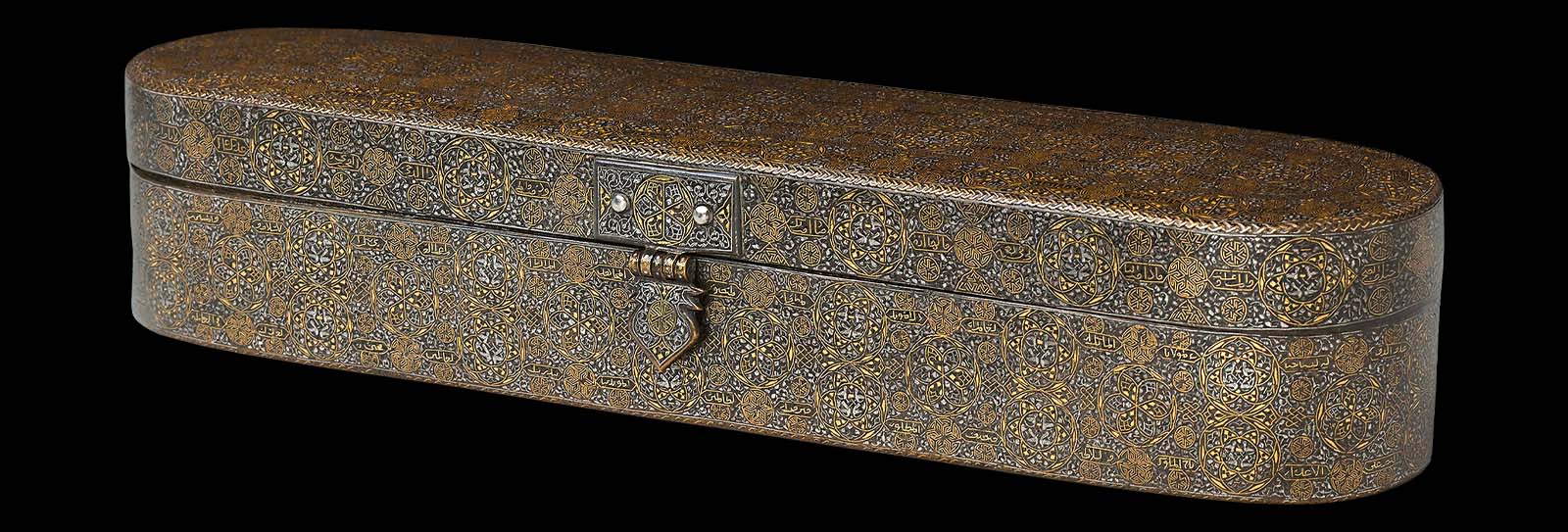

On a heavy incense burner made some 700 years ago, a laudatory inscription in Arabic encircles the name of the sultan. From a distance, the inlaid strokes of its naskhi script burst like golden sunrays. For a small pen case of about the same age, only a close-up view reveals a universe of intertwining inlaid designs where silver birds fly inside golden spheres. So opulent are such pieces that it is hard to believe the amount of precious metal in them is small. Mostly, they are made of a common metal alloy that, in the 12th century CE, metalsmiths in the Turco-Persian Seljuq world transformed into luxury ware. Today, it is as iconic of Islamic art as lavishly illustrated manuscripts or tilework tessellated with arabesques and geometry.

The story takes place in Khurasan, at the time an eastern province of the Seljuq empire whose Persian name means “Land of the Sun.” Its rulers had been in power since the middle of the 11th century and, when it came to feastware, they favored gold and silver for their bowls, ewers and the like. These were made by artisanal metalworkers who decorated them with one or two inscriptions, medallions or bands of geometric or vegetal designs. This ornament was either incised into the surface or shaped in relief by hammering the metal from the reverse side, and large swathes of the precious ore were left plain and undecorated.

In the early 12th century, however, three developments alter the world in which these metalworkers operate. Major silver mines like those of Ilak some 1,000 kilometers northeast of Herat become depleted while copper from sources in Khurasan and neighboring areas remains plentiful. “So there is a change in the availability of materials,” says Beyazit.

Two other things happen. “I don’t know which came first and they might have developed simultaneously,” she says. One is socio-economic: As external enemies and internal rebels destabilize and fragment the empire, the power of the nobility wanes while urban centers witness a growing class of merchants and officials who also have an appetite for luxuries and the means to afford them.

The third phenomenon relates to fashion and taste: People increasingly favor densely decorated objects, figural imagery, lots of color, and what Beyazit calls “an iconography of the courtly cycle,” which includes depictions of feasts, hunts, combat and other aspects of royal life. This new taste is reflected in the reliefs on the walls of palaces and other secular buildings, the designs on ceramics and lusterware, “and it probably also appeared in illustrated manuscripts,” Beyazit speculates, adding that too few of these survived the Mongol invasion of Khurasan in 1220-21 CE to know for sure.

It is against this backdrop that Herat, now in western Afghanistan and then a thriving city in Khurasan and a center for metalwork, became known for a new kind of luxury ware that would flourish and evolve in parts of the Islamic world until about the 17th century. Later, in the 19th century, a variant from the eastern Mediterranean would become the object of a revival.

One of the most startling features of this luxury ware is that it was not made of a precious ore, but instead, of bronze and brass. As art historians Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom described them in 1997 in Islamic Arts, these were “cheaper copper-based alloys” until then used for ordinary, widely affordable wares. “Brass in particular,” they write, “was the medieval equivalent of high-quality plastic today: It was relatively cheap, durable, strong and easy to shape.”

Credit for it becoming fashionable in the early 12th century goes to the metalworkers—possibly to gold- and silversmiths—who found ways to satisfy the new tastes by painstakingly ornamenting objects with copper and silver inlays.

The most well-known example of this look is a celebrated water vessel known as the Bobrinski bucket, so named after the count whose art collection now resides at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. A signature specifies it was made in Herat in December 1163 CE. It is cast in bronze—an alloy predominantly of copper and tin—and bands of inlay encircle its round body. On those bands, horsemen wield spears and shoot arrows, people feast, dance, make music and play backgammon. Elsewhere silhouettes of ducks create an undulating pattern while a garland traces a rhythmic swag above scampering hares and antelopes.

But stealing the show is the inlaid calligraphy. In one band of inlay, faces appear at the top of vertical strokes and, in another, letters sprout heads, torsos and arms, all angled and posed to make them readable both as figures and text. Calligraphers were experimenting with new styles at the time, and this “animated script” was part of “a kind of general explosion of scripts,” says Beyazit, “some very playful.”

An even more elaborate example appears in the so-called Wade Cup, made between 1200 CE and 1222 CE. It is a stemmed drinking vessel that today is part of the collection at the Cleveland Museum of Art, and it carries the moniker of one of the museum’s founders. It is made of brass, an alloy of mostly copper and zinc that became a popular choice for these works. Here the inlay depicts animals, humans and signs of the zodiac inside bands that crisscross and overlap like a ribbon wrapped around the body of the cup. Framing this extravaganza is a strip of human-headed script along the stem and, encircling the rim, a broad band of fully anthropomorphic letters. At first glance, it looks like a festive parade of people striking funny poses and wielding props. It took scholars a long time to figure out that the postures and gestures actually spell out wishes of good fortune to the cup’s owner.

Such sophisticated inlay work began with a technique that laid silver wire into incisions in the metal. While this provided the metalworker with the equivalent of a pen or pencil, the new taste required the equivalent of a paintbrush. This meant the inlay process “had to be adjusted,” says Beyazit.

“You can see the technique better with objects where the inlays did not survive,” she adds, pulling up on her computer an image of a 12th-century inkwell at the Met. She points to areas where the inlays have fallen out: Zooming in, these channels appear small to be sure but deeper and wider than nearby engraved line decorations. Elsewhere in the piece, similar grooves are filled with thin silver or copper wire. They frame a rectangular band, surround a circular motif, follow the wavy strokes of naskhi script and, in simple depictions of animals, demarcate stick-like legs. But other inlaid shapes also decorate this inkwell: triangles and circles, bodies of horseback riders and bellies of animals. Faced with an ever-greater demand for decorative motifs and figures, metalsmiths needed more than wire—they needed silver and copper foil of varying shapes and sizes.

In Précieuses Matières: les arts du métal dans le monde iranien médiéval, Annabelle Collinet, curator in the Louvre Museum’s Islamic department, and David Bourgarit, archeometallurgist and research engineer at the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France, reconstruct the process metalworkers in Khurasan developed to expand their repertoire of imagery and decoration. It begins with the artisan tracing contours of the inlay onto the object with a small punch tool that makes a dotted line. He then chisels and roughens up the area, undercutting along the edges. The scale of the work is minute, measured in micrometers.

So far, this sequence of steps is the same whether executed onto a vessel made of hammered sheet brass or on a wax model used to cast a piece. Next comes the application of a black paste. Its composition is still unclear, but part of its purpose is to help affix the inlay which the metalworker cuts to measure from a thin silver or copper sheet. He now inserts the piece inside the contours, hammers it in to mesh with the roughened surface, and then taps the small overhang created by the undercutting so that it clamps down the edge of the inlay.

“That technique,” says Beyazit, “is new.” Now that inlays of any shape could be snugly secured, the possibilities for inlaid designs exploded, allowing metalworkers to cover the entire surface of a basin, bowl, inkwell, ewer, candlestick, you name it, with imaginative calligraphy, vignettes of court life, playful depictions of animals and intricate patterns vegetal and geometric patterns. In the process, they introduced a colorful mix of silver-white, orange-red copper and black paste against the brass body’s gold-yellow. The choice of metals would later vary, but interplay of color they created became one of the hallmarks of Islamic metalwork.

The technique began to spread widely and rapidly in the wake of the 1220 CE Mongol invasion, as many—some metalworkers among them—fled Herat and other cities, taking with them their knowhow and artistry. Most went west: Workshops in Mosul, now in Iraq, began making inlaid brasses and bronzes, and so did counterparts in Syria and Anatolia. “Under the Mamluks, there is a Cairo-based market of inlaid metalwork for the court,” says Beyazit, and Damascus too continued to flourish as an important center and became a hub for its export to Europe and across the Islamic world.

As various workshops adopted the inlay techniques from Khurasan, they adapted the decorations to local preferences. In the 13th century, for example, some metalworkers in Mosul incorporated Chinese-inspired designs, like the decorative patterns on a tray made for Badr al-Din Lu’lu’, who began life as an enslaved Armenian and died as the ruler of Mosul. Others in the region included Christian iconography such as the scenes from the life of Christ depicted on an inlaid brass canteen held by the Smithsonian Institution’s Freer Gallery of Art Museum. And a third metal color was introduced: gold. In the 14th century CE, its popularity grew across the vast Mamluk Sultanate while that of copper waned and figural depictions gave way to arabesques and inscriptions. In Khurasan itself, metalworkers also refined their techniques over time. Collinet and Bourgarit describe them originally setting the inlay flush with the body of the object, but in the 15th century, setting them in low relief, now accentuating the inlaid designs by having them catch the light just a tad more.

“From afar, it is something shiny,” says Beyazit. “But people know the material. They know the value. So they get close to appreciate it in all its details.” Though she may be referring to audiences in centuries past, Beyazit’s use of the present tense equally describes our own encounters with the ways innovative artisans rendered ordinary alloys resplendent.