African Artists gain traction in the UK

The United Kingdom is experiencing a surge in demand for contemporary art of African origin. For artists of the African diaspora, the UK represents a new arena in which to showcase their messages through unique techniques and mediums. Interest in their work follows mounting pressure on museums, universities and other institutions to “decolonize” their curricula and collections.

African Artists Find Hungry Audience for Their Unique Messages in UK

Three imposing figures are standing on the shoreline. Each measuring more than 10 feet tall, they are dressed in elaborate costumes adorned with jewelry, shells and bottle tops. The colorful figures are set against a pale blue sky with wispy clouds, and behind them stretches a cold northern European coastline.

This image of a West African masquerade transplanted into the north of England was created by British Nigerian artist Ade “Àsìkò” Okelarin. Combining photography with mixed media, his work straddles fantasy and reality to explore his experiences of identity, culture and heritage.

“I am not Nigerian, and I am not British,” Àsìkò said. “I walk this line of duality, and my work is a representation of that.”

The United Kingdom is experiencing a surge of interest in African art that can be traced back nearly 20 years to the Africa Remix exhibition in London. Featuring the work of more than 70 artists from 23 countries, it was at that time the largest exhibition of contemporary African art ever staged in Europe. London now plays host to an annual Contemporary African Art Fair, which in 2023 showcased the work of more than 150 artists from the continent and its diaspora.

The Black Lives Matter Movement has fueled public demand for art of African origin, putting pressure on public institutions, including museums and universities, to decolonize their collections and curricula.

London’s Tate Modern commissioned a huge installation in 2023 from the Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui, who is seen as one of Africa’s greatest living artists. He is best known for his great shimmering tapestries made from thousands of aluminum bottle tops, stitched together using copper wire. In spring 2024, the National Portrait Gallery staged an exhibition of work by artists from the African diaspora, looking at the representation of the Black figure in contemporary art.

London’s Copeland Gallery put on “Seeing Sounds,” an exhibition by House of African Art (HAART), a UK-based arts platform specializing in contemporary art of African origin. (ASIKO)

In his Johannesburg studio, South African artist Azael Langa is about to begin a new piece of work. A canvas is stretched on a wooden frame, with a rope attached to each corner. Langa hoists the canvas until he has space to crouch beneath it. Then he lights a candle, holds the flame up to the canvas and “paints” with the trail of smoke.

Like many of his contemporaries across Africa, Langa has invented his own techniques and discovered his own media. This is sometimes dictated by necessity—the lack or cost of traditional art materials—but also by the artist’s vision and how best to convey it.

“I want to create spaces which are more welcoming and inclusive, where visitors can ask questions about what the artists want to communicate.”

“As I try to control this fire, which moves rapidly with its own intentions and energies, I grasp what it means to attempt to control our individual lives in a world with its own agenda,” Langa said.

His subjects are ordinary people in his community, who, through the medium of smoke, take on a spirit-like quality. His work explores social issues such as isolation, exclusion and exploitation.

“I see myself as an activist for those cast out of society’s normality,” said Langa. “I want to give confidence to Africa and communicate what Africa is to the world.”

Langa has found social media to be his most effective tool in communicating that message, particularly Instagram, which is how he came to the attention of Maryam Lawal, a British Nigerian lawyer and art curator. In 2023 she invited him to participate in a London exhibition of works by emerging artists from South Africa and Nigeria.

Maryam Lawal founded HAART in 2019. (RAZIA JUKES)

Growing up between London and Lagos, Lawal was able to compare the limited selection of African art displayed in British galleries with the striking, innovative work being created in West Africa. “I had a growing sense that more needed to be done in the UK to showcase a greater range of African artists and their works,” she said.

So in 2019 Lawal launched the House of African Art, a UK-based arts platform specializing in contemporary art of African origin. The aim was to break away from the traditional “white cube” gallery in favor of pop-up exhibitions in flexible spaces where visual artworks could be complemented by poetry and music. To find these spaces, she headed to converted industrial buildings in east and south London.

“I think traditional galleries can be quite elitist and intimidating,” said Lawal. “I want to create spaces which are more welcoming and inclusive, where visitors can ask questions about what the artists want to communicate.”

Langa’s “What the city has offered,” 2019, 130x175 cm, smoke and acrylic on canvas. (Image courtesy of AL Studios.)

Artist Azael Langa

“As we wait,” 2022, 200x150 cm, smoke, acrylic and gold leaf on canvas.

Historically, London has been a beacon for artists from Africa, not only because of British colonial rule but also its world-class art schools. Nigerian painter and sculptor Ben Enwonwu, arguably the greatest African artist of the 20th century, moved to the UK in 1944 to attend the Slade School of Fine Art. Sudanese painter Ibrahim El-Salahi followed in his footsteps 10 years later. Some of these artists stayed and worked in the United Kingdom. Others returned to Africa, where they helped to shape their countries’ cultural identity following independence.

Despite these strong connections, there has been little knowledge of African art in the UK until recently. Art-history courses at most UK universities made no mention of African artists, and the permanent collections of most UK public art galleries were dominated by artists from Europe and North America.

“In Western thought, Europe was a space of modernity; Africa was a space of tradition,” said Gabriella Nugent, a London-based art historian and curator. “But this ignores the fact that many African and European artists were operating in the same cities together. I think it’s really important to not perpetuate this idea of modernism as a European project.”

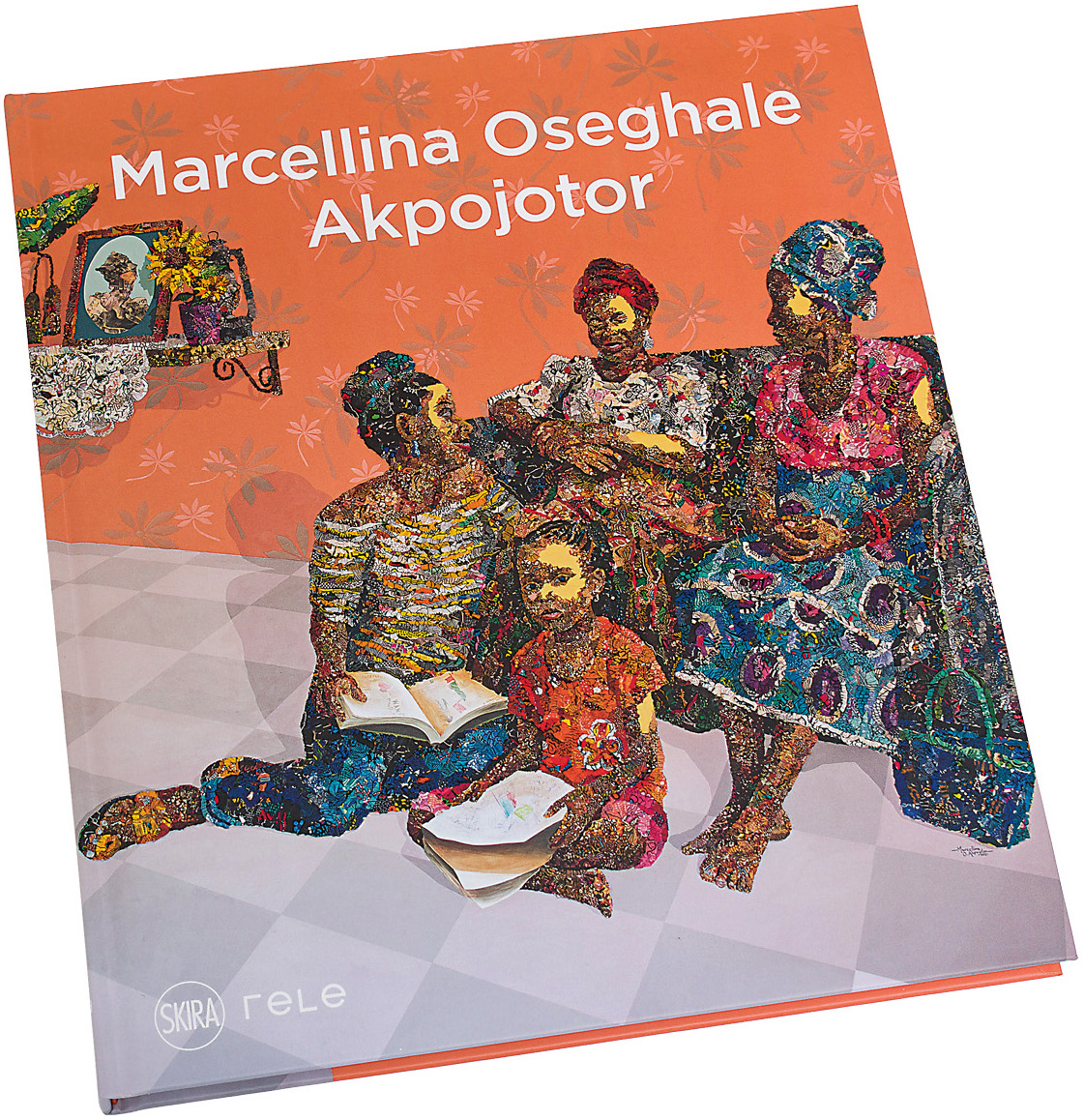

Rele Gallery in London hosted Marcellina Akpojotor’s “Joy of More Worlds” installation this spring. (Images courtesy of Marcellina Akpojotor and Rele Gallery)

The artist makes collages of densely packed fabric pieces to create images of daily life.

There is clear evidence that African art had a significant impact on modern art movements including cubism and expressionism. Early-20th-century artists such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse were inspired by the bold lines and geometric shapes of African masks and sculptures.

But many narrow European preconceptions about African art endured into the late 20th century, despite the inauguration of art biennials in several African capitals and the increasingly global nature of the art world.

“African artists in the 1990s were often expected to perform a sense of ‘Africanness’ in their work, which agreed with Western assumptions about the continent and its people,” said Nugent. “And even in our current moment of decolonization, there is not always a parallel undoing of colonial structures of knowledge.”

In her studio in Lagos, Nigerian artist Marcellina Akpojotor is surrounded by a sea of scraps of African print fabric, rescued from the cutting-room floor of local tailors. The brightly colored, wax-printed cotton is popular among Nigerian women, from the slums of Lagos to business meetings in Abuja.

“I’m drawn to the African print fabric because it feels like my community is contributing to my work.”

Akpojotor collages the fabric pieces densely onto large canvases, creating richly textured portraits of daily life that bridge the past and the present. It is a distinctive artistic process, where the salvaged fabric is not only the medium but also a conduit for collective memory.

“I’m drawn to the African print fabric because it feels like my community is contributing to my work,” said Akpojotor. “The offcuts of fabric that I collect are filled with stories. I do not know those stories, but they have their own energy, and they start a conversation in my work.”

The story of African print has many parallels with the story of contemporary African art in its exchanges with Europe. The fabric, a powerful marker of African identity, was in fact introduced to west and central Africa from the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. A number of contemporary African artists incorporate representations of the fabric in their work to explore cultural identity and the legacy of colonialism.

Marcellina Akpojotor works on a large canvas earlier this year.

The artist’s monograph on her “Joy of More Worlds” show.

Akpojotor brought the fabric from Africa to Europe this year for her first solo art show at Rele, a newly opened, upscale London gallery. Comprising 3,000 square feet of exhibition space over two floors, it is one of a growing number of galleries in London dedicated to African art.

“There have always been amazing African artists,” said Alessandra Olivi, an independent art consultant and curator. “What we are seeing now is the collecting world and institutions asking themselves, ‘Are our collections representative of what is happening out there?’ And actually realizing no, they are not.”

African artists, and artists of African heritage, are increasingly choosing to create art on their own terms. While some continue to explore sociopolitical issues in their countries of origin, others are creating more abstract works.

“I think this is important because it allows artists to continue to develop their own distinct visual vocabulary,” Lawal said. “It’s not all about strife and struggle and having to carry the weight of their nation’s history and colonialism. It can be more abstract, more complex. It can be lighter.”

One artist creating more abstract work is Ayesha Feisal, a British artist of Sierra Leonean heritage who is represented through the House of African Art’s online gallery. Feisal is interested in changing psychological states, which she explores by painting amorphous human forms, using intense and often surreal colors as a way to heighten emotion.

“These artists are broadening perceptions,” said Lawal. “Through their work, they are showing that there is a much greater variety and complexity of subject matter than people may have assumed before. They are providing dynamic, fresh perspectives on contemporary art of African origin.”

Book Reviews From AramcoWorld

A Century of African Artists Claimed Space Before the UK Caught Up.

You may also be interested in...

Muralist Teakster Blends Urban Graffiti and Arabesque Patterns

Arts

History

At once playful and disciplined, Hatiq Mohammed—“Teakster”—uses traditional Islamic motifs, Arabic calligraffiti and deep colors to “join communities together” in public projects of collaborative creativity that energize cultural dialog.

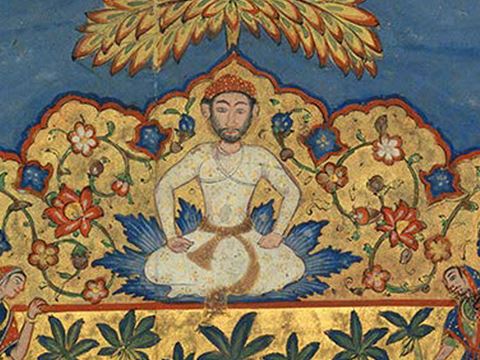

A Conversation With Art Collector Book Editors Peyton and Paul

Arts

In Arts of South Asia: Cultures of Collecting, coeditors Allysa B. Peyton and Katherine Ann Paul draw us into the personal, institutional and political dynamics surrounding objects that have journeyed from South Asia India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Bhutan to museums abroad and, in one case, undergone repatriation.

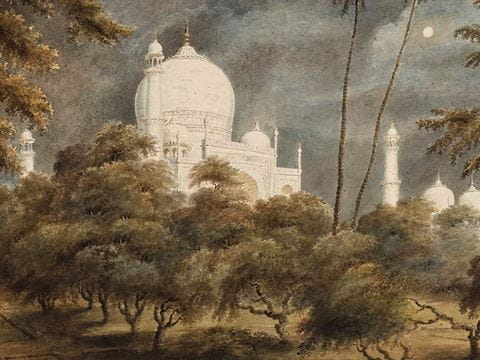

How Historical Paintings of Taj Mahal Changed Perceptions of India

Arts

History

The depiction of the Taj Mahal in the works of Indian and British artists in the 1800s helped bolster enthusiasm for the country & rsquo;s rich culture, architecture and society. One such painting, & ldquo; The Taj Mahal by moonlight,& rdquo; stirred a bidding frenzy at a recent auction, and some experts argue that such paintings have helped change perceptions of India in the West.