A Celebration of Textile Artwork and Heritage at Venice Biennale

The Venice Biennale sheds light on lesser-known narratives outside of the international art world.

Around the world artists are delving into the traditional arts of their respective cultures to develop new works, often textile-based, which preserve the heritage and legacy of their homelands.

Until recently, textile-based art was rarely displayed at museums. The late Anni Albers, a leading 20th-century textile artist from Germany, famously remarked in 1984 that “galleries and museums didn’t show textiles; that was always considered craft and not art. … When it’s on paper, it’s art.” But this all seems to have changed.

Three exhibitions at the 60th edition of the Venice Art Biennale, titled “Stranieri Ovunque—Foreigners Everywhere,” explore embroidery, textiles and traditional art references in commenting on gender roles, identity and migration in South and Central Asia. Championed in all three exhibitions is the role of often overlooked local communities in preserving heritage.

“Cosmic Garden” features the works of Indian artists Madhvi and Manu Parekh, also husband and wife, and the Chanakya School of Craft; “Don’t Miss the Cue” at the Uzbekistan pavilion presents the work of Aziza Kadyri and the Qizlar Collective; and “Collective Behavior” features the largest presentation to date of works by Pakistani American Shahzia Sikander.

Resting Near the Pond 2023 Organic jute, cotton, linen and raw silk thread on cotton textile cm 286 x 340 courtesy chanakya foundation. (Madhvi Parekh, Karishma Swali and Chanakya School of Craft Courtesy Chanakya Foundation)

‘Cosmic Garden’: Chanakya Foundation and Indian artists Madhvi and Manu Parekh

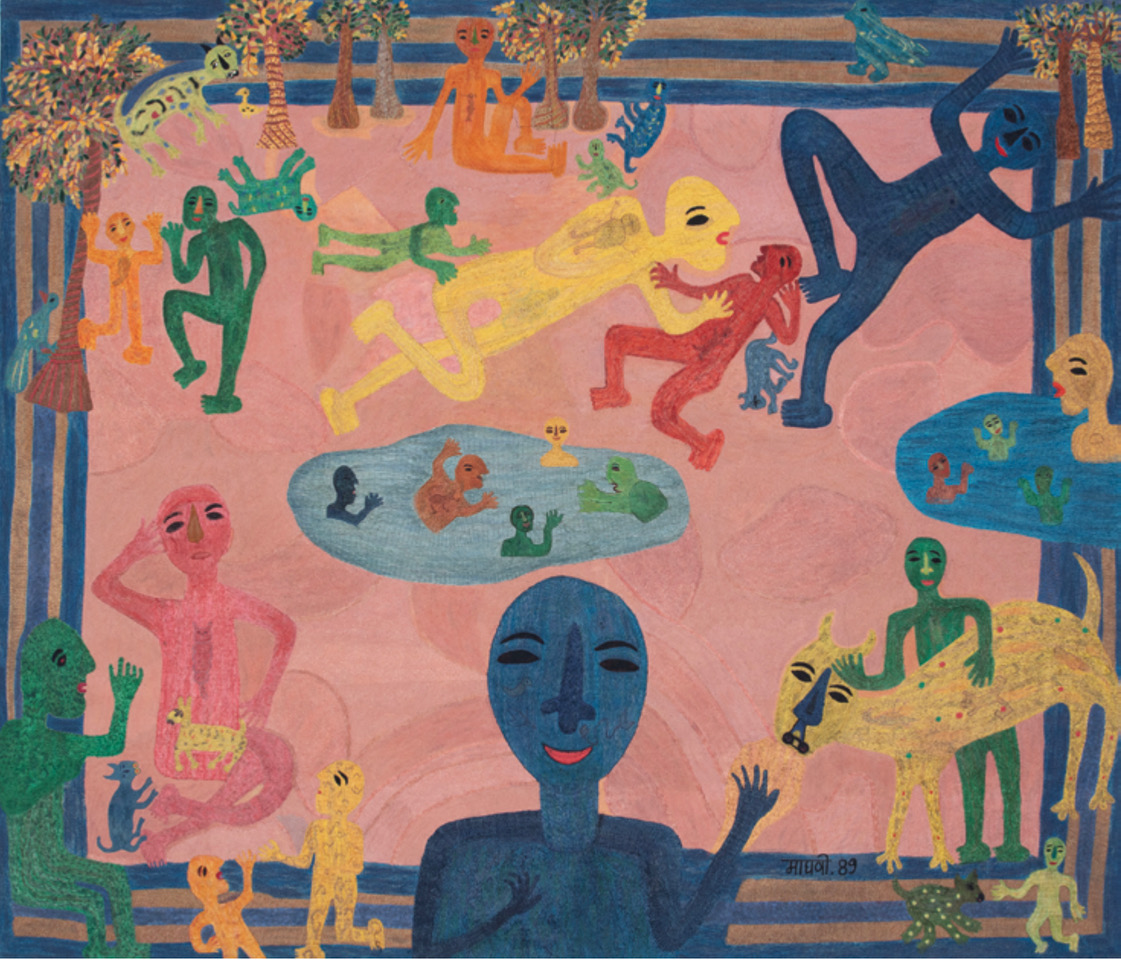

A plethora of vibrantly colored textile works, paintings and sculptures featuring expressionistic mythological figures and forms fills the Salone Verde Art & Social Club in Venice. The exhibition, a collateral event, is the result of a collaboration between the Indian artist couple Madhvi and Manu Parekh, the Chanakya School of Craft in Mumbai and the Italian designer and creative director of Dior, Maria Grazia Chiuri. It celebrates the pluralistic beauty of India’s cultural heritage through paintings, sculptures and hand embroidery.

The show, complementing the theme of the Venice Biennale in shedding light on lesser-known narratives outside of the international art world, highlights the vital role of local communities in preserving Indian heritage and traditions.

Artists Madhvi Parekh and Manu Parekh with Karishma Swali, 2023 (© SahibaChawdhary Courtesy of Chanakya Foundation)

“Traditionally, handcraft skills in India are passed from fathers to sons,” says Karishma Swali, the creative director and managing director of Mumbai’s storied textile and embroidery house Chanakya International and the Chanakya School of Craft. “However, our school is unique in that it not only teaches the art of hand embroidery but also exposes our female students to various facets of culture and design. This revaluation of the relationship between women and embroidery marks a significant shift in how we perceive this timeless craft.”

The female divinities of Madhvi Parekh, largely influenced by Hindu mythology, and the evocative abstract paintings of her husband, Manu, are given a new form through the meticulous hand embroidery and traditional knowledge of the artisans of Chanakya.

The result is aesthetically otherworldly due to its artistry and mission behind the collaboration. Since its founding in 1984, Chanakya International has committed to the preservation of India’s artisanal crafts. Composed of master artisans representing around a dozen generations of professions working in traditional craftsmanship and hand embroidery, the company has supplied hand embroideries to numerous global luxury brands. Swali also runs the Chanakya School of Craft , a nonprofit that she co-founded in 2016, to preserve Indian craft and textile art and empower low-income women.

Madhvi says she always had an interest in working with the craft. “I experiment with my painting, and this was the first time that craft and painting came together in my work,” she notes.

Friends at Play 2023 Hand-sculpted paper mache with organic jute, linen and cotton thread cm 132 x 97 x 183 (Madhvi Parekh, Karishma Swali and Chanakya School of Craft Courtesy Chanakya Foundation)

To interpret Madhvi’s work, laden with female iconographies, the artisans at the school employed a primitivist expression. “They used dimensional techniques in repetition to create background textures that evoke a magical world of folktales and pastoral scenes populated by village deities, forests, animals, children and amorphous forms,” explains Swali. “Additionally, techniques such as couching and fine-needle zardozi stitches were used to achieve a sfumato effect, allowing tones and colors to blend gradually, creating softened outlines and hazy forms.” In one work, “Devi and Asura” (2023), the representation of good and evil is visually rendered through an interplay of colorful threads. The piece employed more than 32 handcraft techniques and required over 16,100 hours of work by 30 highly skilled artisans.

Manu Parekh’s modern abstractions, inspired by his interest in philosophy and spirituality, presented another challenge. His “Chant” series seeks to transform sound energy into aesthetic form. “This inspired us to explore the vibrancy of chants through thread,” says Swali. “We utilized traditional Indian embroidery techniques alongside contemporary design principles to create pieces that capture the dynamic energy and cultural depth of his paintings.”

After agriculture India’s craft sector is the second-largest employer, with more than 200 million artisans. “The entire sector comprises mostly women,” says Manu. “In India, women have always been linked to craft roles. However, embroidery as a profession has been reserved for men.” It is for this reason that Chanakya School of Craft is so vital to the empowerment of women. As Swali explains: “By actively showcasing embroidery in global exhibitions, we question assumed hierarchies while challenging entrenched gender norms in the artistic process.

Don’t Miss the Cue, installation view. Artist Aziza Kadyri addresses issues of belonging and identity through the experiences of women from Central Asia, offering insight into how they navigate and redefine themselves in the migration process. (Courtesy of ACDF / © Gerda Studio)

‘Don’t Miss the Cue’: Aziza Kadyri and the Qizlar Collective

A predominance of textiles can also be found in “Don’t Miss the Cue,” an installation by Uzbek artist Aziza Kadyri and the Qizlar Collective for the Uzbekistan pavilion.

Inside a darkened space, larger-than-life multilayered blue textile panels have become sculptured costumes set within the backstage of a deconstructed theatre. The works present a collaboration between Uzbek London-based artist Kadyri and the Tashkent-based grassroots feminist collective and community of young contemporary artists and creators, of which Kadryi is the co-founder.

Aziza Kadyri (Courtesy of Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation)

Don’t Miss the Cue, installation view. (Courtesy of ACDF / © Gerda Studio)

The project, led by Kadyri, addresses belonging and identity among women in Central Asia, particularly those migrating to new countries. The exhibition draws visitors through the deconstructed theater backstage emulating Houses of Culture, key institutions for cultural activities and state-implemented cultural policies during the socialist era throughout Eurasia during the early 20th century. The setting, evoking that of a performance, places textile-based sculptures center stage. The installation is accompanied by audiovisual materials by Qizlar.

The exhibition reflects the Biennale’s theme of Foreigners Everywhere. “How do we embody the character of a ‘foreigner?’ asks Kadryi, who collaborated with Madina Kasimbaeva, a master of Suzani, a type of embroidery and decorative tribal textile made in Central Asian countries. The installation echoes the decorative patterns found in Suzani yet is made contemporary through various abstract and geometric forms in varying shades of blue that seemingly create an abstract painting.

Don’t Miss the Cue, installation view. (Courtesy of ACDF / © Gerda Studio)

The shapes on the fabric, says Kadyri, come not only from her collective memories but are also inspired by Sofia Seitkhalil’s photographs of urban spaces in Tashkent (Seitkhalil is also part of Qizlar).

Kadyri, whose background is in theater design, was born in Russia and has lived in mainland China and Taiwan. “Much of my practice is about trying to rediscover my roots and what it means to be Uzbek today in this era of post-independence as a person in the diaspora,” she says.

The installation, like “Cosmic Garden,” also strongly focuses on the emancipation and empowerment of women. Qizlar is a grassroots feminist collective that seeks to empower Uzbek women to join the creative industries, which, according to Kadyri, are largely dominated by men in Uzbekistan. All members of Qizlar are female.

Sketch by Aziza Kadyri (Courtesy of Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation)

“I have been practicing embroidery for 25 years,” says Kasimbaeva in the exhibition’s opening press release.“During this time, over 500 female embroidery students have collaborated with me. I have dedicated my entire life to the concept of ‘female collectivity.’ Embroidery is a task that cannot be undertaken alone. It requires a team, and in our case, a women’s team.”

“Don’t Miss the Cue,” a title that Kadyri chose for its association with performance, is about the power of female collectivity anchored in tradition. As Kasimbaeva notes: “Even in ancient times, when every girl embroidered her dowry, her relatives and friends assisted her. The work of a master is a continual pursuit. Aziza and I exemplify the idea of female collectivity through embroidery.”

Tradition here also embraces the future through artificial intelligence, with the recognizable patterns of Suzani processed by AI not only to reinterpret Central Asian heritage but highlight the rapid changes of the modern world and indicate the long-lasting effects that technology will have on culture and identity.

Shahzia Sikander’s Fixed, Fluid, 2022: Glass mosaic with patinated brass frame. (Courtesy of Dr. Fatima Zuberi, © Shahzia Sikander.)

“Collective Behavior”: Shahzia Sikander

Female representation through traditional art, this time in the form of South Asian historical manuscript painting, is also at the core of “Collective Behavior,” the most comprehensive showing to date of works by Pakistani American artist Shahzia Sikander.

“‘Collective Behavior’ proposes kinship systems between experience, consciousness, race and culture,” explains Sikander. “The works in this exhibition address many themes close to my heart, including centering women’s narratives among uneven power relations and ongoing legacies of colonialism.”

The exhibition was curated by Ainsley M. Cameron of the Cincinnati Art Museum and Emily Liebert of the Cleveland Museum of Art. It features key works from the 1980s to the early 2000s alongside new site-specific drawings and glass pieces that explore the history of Venice as a city for global cultural and economic exchange. The works also explore the cultural complexities surrounding Central and South Asian historical manuscript painting and Sikander’s interest in female representations.

Artist Shahzia Sikander (Photograph by James Mollison)

“Venice is the perfect location to further explore these ideas,” says Sikander. “The traces of cultural trade and connection are evident on every Venetian façade and in the city’s paintings, frescoes, sculptures and textiles. Such exchanges are reflected in my work as interlinked and morphing forms, conveying syncretic visual histories, including the nonbinary feminine protagonists.”

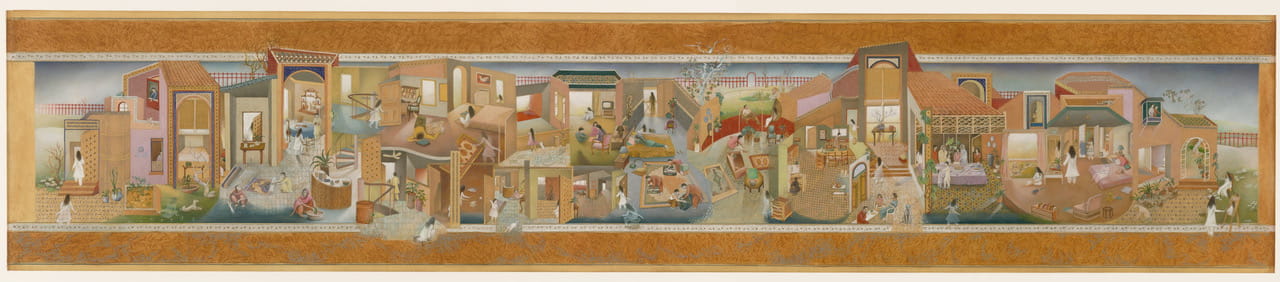

The show begins with “The Scroll” (1989-’90), a pioneering work the artist created for her graduate thesis at Pakistan’s National College of Arts in Lahore, where she was taught the traditional discipline of Indo-Persian miniature painting. Using intricately rendered classical Indo-Persian miniature painting as its base, she applied watercolor and gouache on tea-stained wasli paper to capture a multitude of intricate scenes that continually capture the viewer’s attention. The work marks the artist’s longtime engagement with and disruption of South Asian artistic traditions by merging techniques found in traditional art forms within the new structures of contemporary art.

The Scroll, 1898-1990: Vegetable color, dry pigment, watercolor, and tea on hand-prepared wasli paper, 1989-1990 © Shahzia Sikander

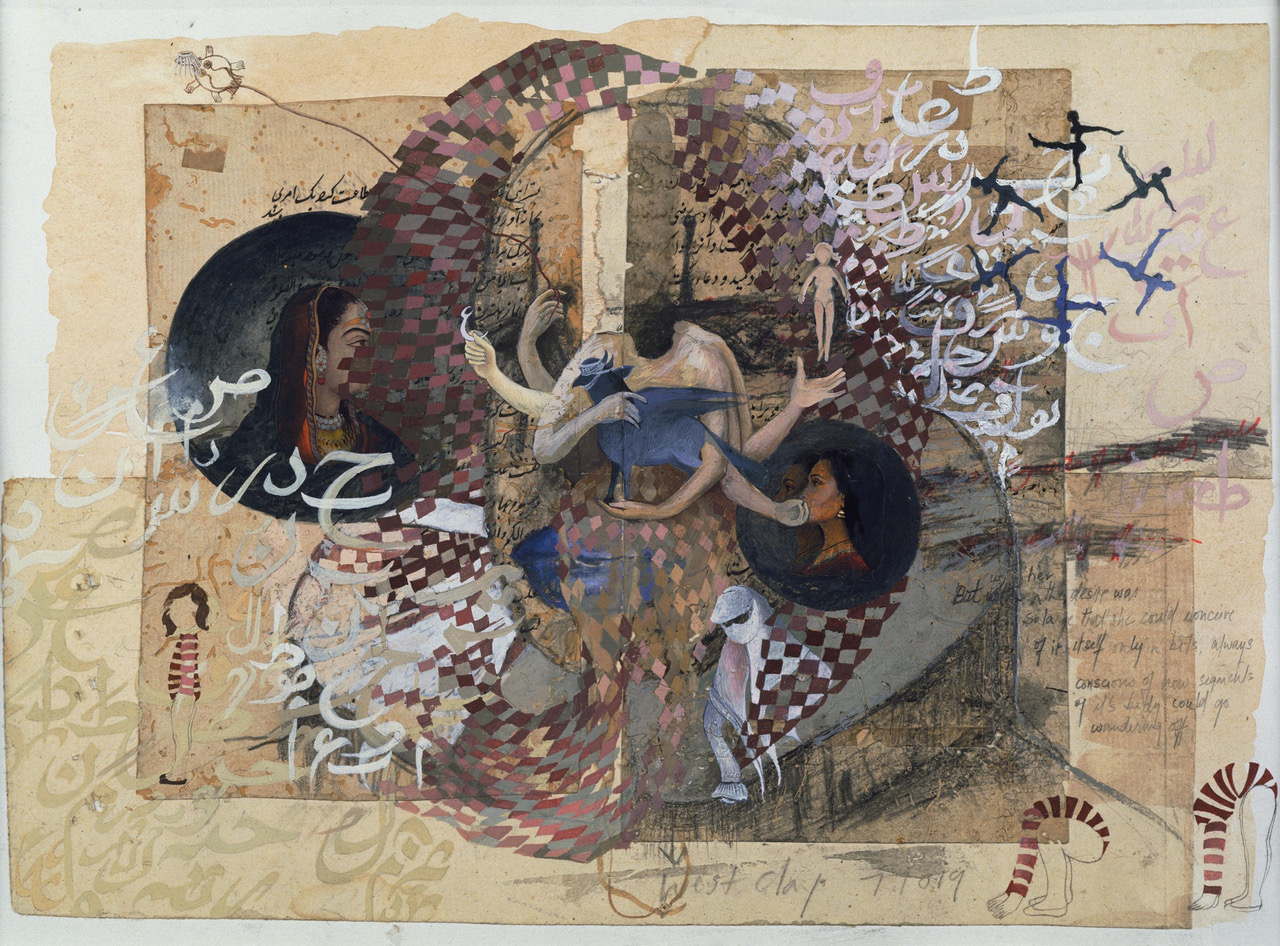

In a more recent work on view titled “Arose”(2020), two intricately depicted women in miniature are found in the center with what appears to be their robes extended out and repeated in a circular fashion. Made from glass mosaic with patinated brass, the piece serves as an example of how Sikander has both incorporated traditional miniature painting and distorted it within a contemporary, more disruptive style.

“One of the aspects that is notable about Shahzia’s work is the way she’s developed this kind of lexicon of forms and figures that has developed and gained force over time,” says Emily Liebert, curator of contemporary art at the Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland, Ohio.

Segments of Desire Go Wandering Off, 1998: Collage with vegetable color, dry pigment, watercolor, graphite, and tea on wasli paper (Courtesy Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg, New York, © Shahzia Sikander)

Arose, 2020: Glass mosaic with patinated brass frame (Courtesy of Joel S. Pizzuti, © Shahzia Sikander)

The exhibition is divided into three sections: “Point of Departure,” exploring her engagement with South Asian and Persian historic manuscript illustrations; “The Feminine Space,” showcasing her ongoing exploration of gender and body politics; and “Negotiated Landscapes and Contested Histories,” charting the complex histories and effects of colonialism on culture, language, trade and migration in South Asia.

“Shahzia uses the past to offer us a narrative that sheds light on our present moment,” adds Liebert. “And one way she does that is by putting women at the center of her narrative.”

In “Fixed Fluid” (2022), dozens of colorful glass mosaics form a detailed depiction of a long, embellished gown and fitted short-sleeve shirt surrounded by a garden of flowers. Missing is the woman’s head. The work offers an example of how Sikander incorporates miniature painting and distorts within a contemporary style to comment on women who defy stereotypes. Sikander’s women, like those in “Cosmic Garden” and referenced by Kadyri and the Qizlar Collective, defy age-old female stereotypes. They do so by revisiting the past through traditional art forms, empowering women to become imaginative, otherworldly beings, immeasurable in their powers and capabilities. They create, as Sikander would say, their own “collective behavior.”

The Venice Biennale runs through Nov. 24.

You may also be interested in...

Kummah, the Embroidered Crown of Omani Traditional Dress

Arts

Using as its base either calico or other stiff cotton cloth, the kummah is a link to the region's past as well as a personal statement for the present.

Nakshi Kantha Embroidery: Tales of Heritage and Revival

Arts

History

A traditional form of quilting in Bangladesh in which women embroider family history, love and memory into the fabric is blanketing markets locally and beyond.

Spider Silk Weaves Web of Intrigue in Middle East Debut

Arts

Creators Simon Peers and Nicholas Godley present three exquisite textiles and a cape made from the silk of golden orb-weavers found in Madagascar.