The Gambia’s Groundnuts: Identifying Problems and Solutions

Environmental Studies

Anthropology

West Africa

Identify the challenges facing growers of the Gambia’s most-important product—the peanut.

The following activities and abridged text build off “Is the Sky the Limit for The Gambia’s Groundnuts?”, written by Tristan Rutherford and photographed by Samantha Reinders.

WARM UP

Before reading this article or doing the activities, hypothesize the main idea of the article and pose questions you predict the article will answer.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

Complete a graphic organizer to examine problems facing the peanut industry in the Gambia and actions being taken to solve them.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

Create publicity for a new business that is part of the revitalization of the Gambia’s groundnut industry.

VISUAL ANALYSIS

Analyze two photos of individuals, examining how a photographer’s choices about focus and context affect viewers.

Directions: As you read, you will notice certain words are highlighted. See if you can figure out what these words mean based on the context. Then click the word to see if you’re right.

Is the Sky the Limit for The Gambia’s Groundnuts?

It’s late morning as the sun shimmers off the broad mouth of The Gambia River. Businessman Tasmir Saho sits atop a ferry boat traveling between Banjul, the capital of Gambia, and Barra, the semirural port on the north bank of the river. He has built a thriving business in groundnuts, commonly known as peanuts. Groundnuts are the main cash crop in Gambia. The crop takes up one third of the country’s arable land. One quarter of Gambia’s population is associated with groundnuts. The Saho family has grown groundnuts for three generations. Tasmir now oversees three of the nine largest groundnut processing plants in Gambia.

Question: Provide evidence to show that groundnuts are a major part of Gambia’s economy.

Groundnuts are the main cash crop in Gambia. One third of Gambia’s arable land is in groundnuts. One quarter of Gambia’s population is associated with groundnuts.

Suddenly Saho’s cell phone rings. He reaches into the pocket of his kaftan. He converses with the caller in a mix of his country’s nearly two dozen languages. He is an example of the diversity of Gambia, the smallest of the 48 African countries. As he ends the call, he glances over at his smartphone to access the weather app. He checks the weather every morning, even before he checks in with his wife.

Groundnuts are very weather dependent. The Atlantic Monsoon pours some 800 millimeters of rain onto the Gambian uplands every year. The rainy season only lasts 40 to 50 days. During this time, the natural precipitation turns the sere bronze landscape into an emerald carpet of vegetation. But climate change is forcing adaptations and inspiring innovation in Gambia’s agricultural industry.

Modou Touray leads the agribusiness department of the Youth Empowerment Project (YEP), a nationwide program, backed by the European Union, safeguarding Gambia’s agricultural future. He has been observing the climate changes and assessing the challenges facing the groundnut industry. “What we are seeing is changes in rainfall … along with increased pollution,” says Touray. “This has affected groundnuts more than other agricultural sectors.” The monsoons are not always distributed evenly. Sometimes half of the precipitation falls in a few days rather than evenly over the five-month growing season.

Records kept by the World Bank back up Touray’s observations. Monthly rainfall has decreased at a rate of 8.8 millimeters since 1960. Temperatures have increased 1 degree Celsius over the same period. As a result, crop yields are lower than they were in the 1960s and ’70s. Erratic rains mean seedlings can fail and even mature seed pods can yield smaller peanuts. This means less income to the farming family. Groundnuts have always been Gambia’s number-one crop. But the industry faces many other problems beyond the weather: a lack of modern equipment, less arable land and the high cost of farming.

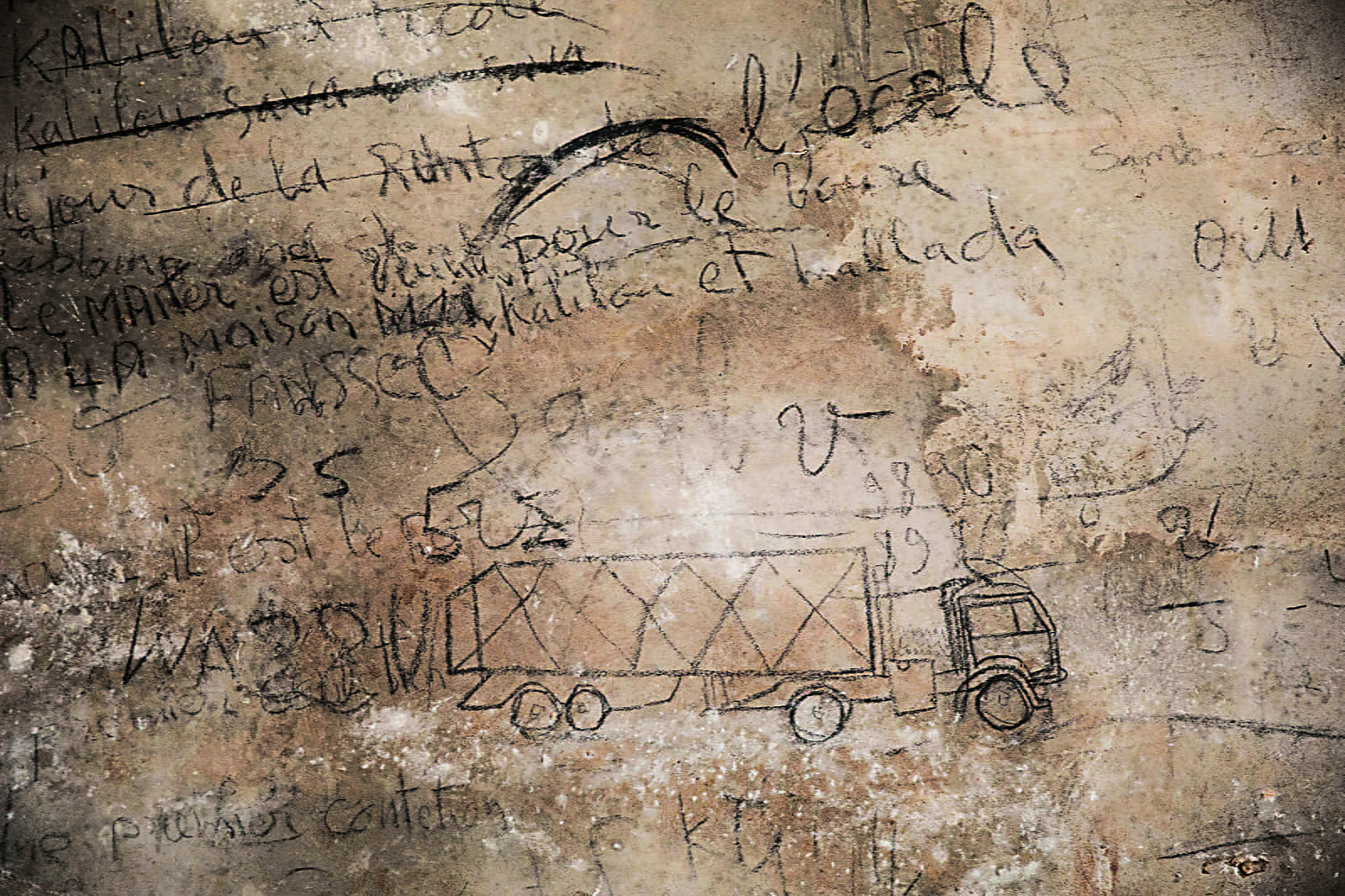

As a result, farming has been losing its appeal among young people in Gambia since the 1990s. Many farmers wonder if their children and grandchildren will follow them to the fields and carry on the tradition. The exodus of young Gambians from farms on the north side of the river to the more urbanized south side has disrupted life. The cities offer hustle and excitement on every corner. A medley of voices and noises attract many young people. More than this, the urban south offers job opportunities. Many people have a trade such as selling wheelbarrow parts or biscuits or bags of pre-peeled oranges. Others sell shelled coconuts, fishing rods, drinking water in small bags or hats to guard against the sun. Since the 1990s, the percentage of young people moving from rural to urban areas has increased from 17 to 28 percent.

Question: What are some of the challenges Gambia’s groundnut industry faces with climate, farming operations, and keeping young people involved?

Possible answers may include the following: Rainfall has decreased and temperatures have increased. Rainfall is erratic. There are other problems with lack of modern equipment, less arable land, and the high cost of farming. Farming has been losing its appeal among young people in Gambia.

The National Food Security Processing & Marketing Corporation (NFSPMC) plant in Banjul is one of the country’s largest. The nozzle vacuums the whole groundnuts from cargo barges and drops them onto a conveyer belt. Most will be destined for export.

Many young people also travel to other countries to find employment and a future. “There were a lot of young people risking their lives to get to Europe by crossing the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean Sea,” Touray says. But he sees incentives in the groundnut industry that can retain young, talented, and enterprising individuals.

At YEP “we took a market-led approach to the economic root causes of irregular migration,” and, he continues, Agribusiness drives Gambian employment and groundnuts are a key subsector. The people at YEP saw the greatest potential for jobs and income for young people in groundnuts.

Since 2017, YEP has concentrated on vocational training. It creates export opportunities for small businesses and job opportunities for young adults. “We have trained more than 5,000 young people and purchased over 100 groundnut machines,” he says, including roasters and peanut-paste presses. The government has also introduced new groundnut varieties, like brocous. It can be harvested in just 100 days and offers is resistant against drought.

Touray sees youngsters eager to introduce contemporary technology into groundnut farming and processing. YEP had funded training on the installation and repair of photovoltaic solar panels. They can power irrigation systems to increase water retention during irregular rains. They also have trained young people on micro gardening to produce extra food an income. This will serve as a buffer against the increasingly high risks associated with small farming.

The Brikama Market is about an hour south of Gambia’s capitol of Banjul. Innovation has permeated the market. Here hundreds of stalls sell all varieties of processed groundnuts. Technology takes the form of new roasting machines that can roast a 60-kilogram bag of peanuts in half an hour. This is a value-added improvement over the wood-burning roasters fueled by tree stumps that could roast about 10 kilograms, or about 22 pounds.

Question: Describe some of the innovations the organizations like Youth Empowerment Project and Gambia’s government are doing to safeguard Gambia’s agricultural future.

Possible answers may include the following: YEP has concentrated on vocational training. Introducing new groundnut varieties that can be harvested in just 100 days and are drought resistant. New technologies like solar panels to power irrigation systems and micro-gardening and new roasting machines.

Nothing is wasted in the groundnut value chain, and the husks are used as fertilizer.

Not far north of the Brikama Market is the annual Trade Fair Gambia International. Some 500 exhibitors showcase goods ranging from textiles to handicrafts. A DJ plays music and dozens of kiosks offer a wide range of food. One company that sells there is Favourite Foods, founded by 19-year-old Kumba Jobe. She displays slickly packaged Gambian snacks like groundnut-coco, a savory mix of spiced ground nuts with nutmeg, coconut and ginger. Each package lists the nutritional benefits of antioxidants, potassium, and calcium. Other products from Favorurite Foods include churagerrtah, a ready-made mix of pounded peanuts and rice along with cooking instructions to turn the mix into a delicious porridge, perfect for the young 21st-century urban processional.

Also marketing her products at the fair is 20-year-old Adama Ceesay. She started her own business Adama’s Processing Center. She makes groundnut oils and peanut butters. The packaging contains aspirational adjectives like “pure” and “unrefined.” Overseas customers are looking for one thing—quality, asserts Ceesay. Because she sources her products from local farmers, she knows the level of quality. This means she can undercut her competition by purchasing the raw materials for a lower price. “I sell my [largest] product at 1,750 Dalasi [about $32] compared to the imported oil, which costs about 2,100 Dalasi.” Ceesay has set her eyes on markets beyond Gambia, selling on Facebook. Business is so good that she needs to hire some staff to help her.

Question: Review the stories of the two entrepreneurs at the Trade Fair Gambia International. Identify marketing strategies they use.

Possible answers may include the following: Kumba Jobe’s strategies of displaying slickly packaged snacks, listing nutritional information, having a variety of products and including cooking instructions. Adama Ceesay’s strategies include aspirational packaging, using high-quality ingredients sources from local farmers, and expanding her market beyond Gambia.

Back on the banks of the Gambia River, Tasmir Saho’s day of making rounds of groundnut processors in Barra is nearly done. Heading back to Banjul on the ferry, he again scrolls through his smartphone—this time for the WeChat app, a free messaging app. Saho is ready to ship another container of groundnuts to China. Shipping costs, however, have nearly doubled since the COVID-19 pandemic. A container from West Africa to China that cost $2,500 two years ago has spiked to $4,000, resulting in tough negotiations over WeChat. But none of this seems to much trouble Saho’s ambitions. As the ferry ride comes to an end, Saho positions himself to be one of the first off. He’ll be back again tomorrow.

Other lessons

The Past Is Told by the Victors: Exploring the Other Side of History

Art

History

Fertile Crescent

Explore how history’s narrative is dictated by the victors and its affect on our understanding of it.

Tracing the History and Geography of Portuguese Tile Making

Geography

Architecture

Europe

Analyze how culture and technology have changed the ways tiles have been made in Portugal for over 500 years.

Taarab Music: Exploring the History and Cultural Impact in Zanzibar

Art

History

East Africa

Explore taarab’s cultural roots, sound and instruments—then compare its emotional and social impact to music in your own life.