Breaking the Shanidar Neanderthal Stereotype: Evidence Based Analysis

Archeology

History

Museum Studies

Fertile Crescent

Julie Weiss

For over a century, archeologists believed Neanderthals were brutish, unintelligent and emotionless. They theorized Neanderthals were not directly related to modern-day humans. Recent archeological studies have dispelled many of these myths through DNA and archeological analysis. Lesson activities have students analyze these stereotypes and recent scientific evidence to the contrary.

The following activities and text are abridged from “Shanidar Cave Yields New Signs of Neanderthal Emotions,” written by Graham Chandler.

WARM UP

Before reading the article or doing the activities, students will complete this warm up to hypothesize the theme and main ideas of the article.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 15 MINUTES ...

In this activity, students will build a compare-and-contrast chart examining the differences between the Neanderthal stereotype, the Shanidar Neanderthal and modern humans.

IF YOU ONLY HAVE 30 MINUTES ...

In this activity, students will examine how and why inherent bias influenced the characterization of Neanderthal culture by early 20th-century archeologists.

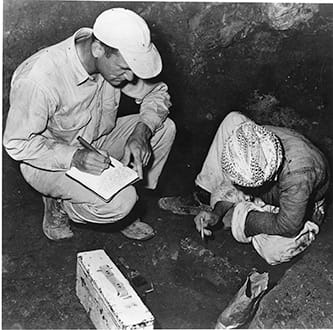

VISUAL ANALYSIS

In this activity, students will explore how to visually analyze images to formulate an impression, then test that impression by reading the captions for further information.

Directions: As you read, you will notice certain words are highlighted. See if you can figure out what these words mean based on the context. Then hover over the word to see if you’re right.

Shanidar Cave Yields New Signs of Neanderthal Emotions

Were Neanderthals the brutish cavemen that populate the movies? Or did they think and feel like we do?

That’s the question that archeologist Ralph Solecki first asked in the 1950s. Solecki and his team found the remains of 10 Neanderthal people at a site in Northern Iraq called Shanidar. What he found most interesting was flower pollen that seems to suggest that the 10 people were buried with flowers. Solecki wondered if the flowers were part of a grief ritual, like those people today practice. And if so, what else might Neanderthals have been capable of?

Another piece of evidence suggests they may have cared for the sick and disabled among them. Solecki and his team found the remains of a man who seems to have survived many serious injuries at a young age. The injuries likely limited his physical abilities, and yet he lived to be about 40, which was old for his time.

No one knows for sure if Solecki’s hypotheses are true. But they have fueled decades of analysis and debate by scholars. Archeologist Graeme Barker is one of those scholars.

In 2011 the Kurdistan Regional Government invited Barker to come to Shanidar and reexamine Solecki’s findings. It is the first such invitation issued since 1960. In 2016, Barker and his team opened their investigation. They planned to use scientific techniques, like DNA analysis, that didn’t exist when Solecki made his bold claims.

They found more than they expected.

They uncovered the body of a man they named Shanidar Z. All the evidence suggested that he had been carefully placed there. For example, the body was lying on its back. The head and shoulders were raised on a triangular stone. The head was turned slightly to its left and set to rest on the closed left hand as if in a dreamy sleep.

The team also found pollen. They aren’t yet sure if it came from flowers (as Solecki found). But Barker says, “the cumulative evidence is looking more and more like the undeniable evidence for a deliberate burial associated with ritual behavior.”

If that’s true, it suggests that the grave is an example of what archeologists call “mortuary behavior.” This takes place when people don’t just bury a body but perform rituals around it, like nearly all cultures do today.

As significant as they may turn out to be, Barker’s findings are far from isolated. Among the research that Solecki’s hypotheses helped launch, four findings stand out, and all have supporting evidence.

Neanderthals prepared some foods.

Robert Power, a researcher in Munich, analyzed residue on Neanderthals’ teeth. He found that they were mostly carnivorous (meat-eaters). But he also found evidence of plants like chamomile and yarrow. He believes these plants were used for flavoring and medication. He also found that Neanderthals ate olives, which actually required processing.

Neanderthals embraced technology.

And it was more than spears and stone axes, says Bruce Hardy, professor of anthropology at Kenyon College. Excavating a Neanderthal site in France, Hardy’s team found unusual fibers attached to stone tools. Very close examination revealed that the fibers were part of cord.

Making cord is complicated, Hardy explains. Layers of inner tree bark are woven into yarn. The yarn is then twisted in the opposite direction to prevent unravelling. This forms a cord. Cords are twisted together to form rope. Ropes are laced to form knots. “It takes a good bit of imagination and mathematical understanding.” It raises the possibility of bags, mats, nets, fabric, baskets, structures, snares and even watercraft.

“There’s no reason to think Neanderthals are cognitively any different than we are,” says Hardy.

Neanderthals made art.

In 2015, Paul Pettitt, professor of archeology at Durham University in the UK, analyzed samples of more than 1,000 red-and-black paintings and engravings on cave walls in Spain. Three images particularly interested him. One was a red linear motif. Another was a stencil of a hand. And the third was red-painted stalactites and stalagmites.

Pettitt and his team dated the art to more than 64,000 years ago. That predates the arrival of modern humans in Europe by at least 20,000 years. The inescapable implication is that the artists must have been Neanderthals.

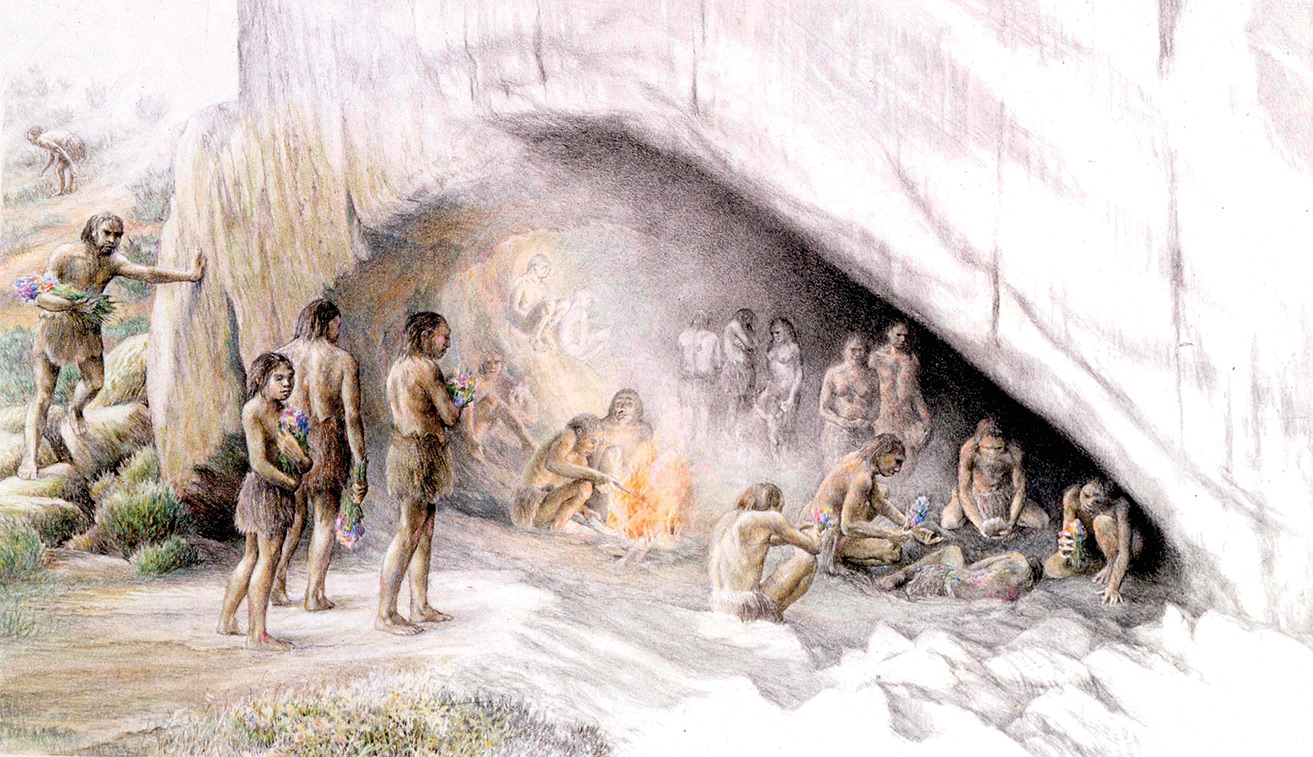

An artist’s impression of a Neanderthal burial at Shanidar Cave draws on the finds of Solecki and Barker to show a community gathering and laying flowers around the body of the deceased.

But not all scholars agree with Pettit’s analysis. They challenge his use of standard Uranium-Thorium (U-Th) dating and say it’s necessary to use other methods too. But Pettitt stands by his results. “We actually sample in the paint itself, and when we have exposed the pigment underneath, we stop.”

The idea that Neanderthals likely were able to sketch on walls further contributes to understanding their cognitive abilities.

“The overwhelming majority of cave art remains undated,” Pettitt says.

Neanderthals could be attractive.

Did Neanderthals interbreed with humans? After all, the two species shared large swaths of territory for 10,000 years.

The answer is largely settled: yes.

Greger Larson, of Oxford University, notes that many studies show that Neanderthal DNA and human DNA have mixed. In people today, the amount of Neanderthal DNA varies--from less than one percent to more than two percent depending on heritage.

“Neanderthals and humans are so closely related they are as similar as wolves and coyotes,” he says. And wolves and coyotes readily intermix.

From his work in France, Hardy has also theorized on interbreeding.

“To think of something as closely related to us as Neanderthals are, to think that they don’t have symbolic thought when ultimately we are seeing through DNA evidence that they are interbreeding with modern humans’ ancestors—it doesn’t make any sense,” Hardy says. “Why are we going to interbreed with something incapable of symbolic thought?”

Hardy reckons the shared DNA and evidence of interbreeding suggest something further.

“At some level, we’re not really talking about Neanderthals going extinct, he says. “We’re talking about assimilation, where part of the Neanderthal genome is brought into the modern human.”

Or as Larson puts it, if Neanderthals were alive today, they could blend in on a bus in any city, particularly in Europe or West Asia.

The discoveries at Shanidar Cave and elsewhere add that not only would the Neanderthals blend in, but any one of them might give up a seat for a less able passenger. Or hold the door.

Barker hopes Shanidar Cave will continue to reveal more answers. Every scrape of the trowel, every swish of the brush, every microscopic soil analysis promises clues to come.

Other lessons

Visualizing From Where Food Comes: Teaching Environmental and Social Impacts of Global Farming

Environmental Studies

Geography

Examine global food production through George Steinmetz’s aerial imagery and evaluate how farming affects people, ecosystems and sustainability.

When Postcards Bring the Past Alive, Curiosity Follows

For the Teacher's Desk

Placed in students' hands, century-old postcards unlock investigative thinking and spark the kind of inquiry every teacher hopes to cultivate.

The Legacy of Borchalo Rug-Weaving in Georgia: Explore Cultural Change Through Critical Reading and Design

Art

History

Anthropology

The Caucasus

Analyze efforts to preserve a centuries-old weaving tradition, and connect the Borchalo story to questions of identity, memory and heritage.