The Arabian Lion

Grown, they look like dragonflies, but at the larval stage the ant-lions — squat, tough, and as fierce as the real thing — not only feed on ants, but dig pits in which to trap them.

This article appeared on pages 10-11 of the January/February 1982 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

The African lion, unfortunately, has been extinct in Arabia for the last 100 years, but there are still lions in Arabia. Admittedly they're tiny, but proportionately they are every bit as ferocious as the real thing—and a good deal smarter. They're called the ant-lions.

Known to scientists as Myrmeleontidae, in the order Neuroptera, the ant-lions are common throughout Arabia, but few people recognize them - and even fewer know of their unique life style.

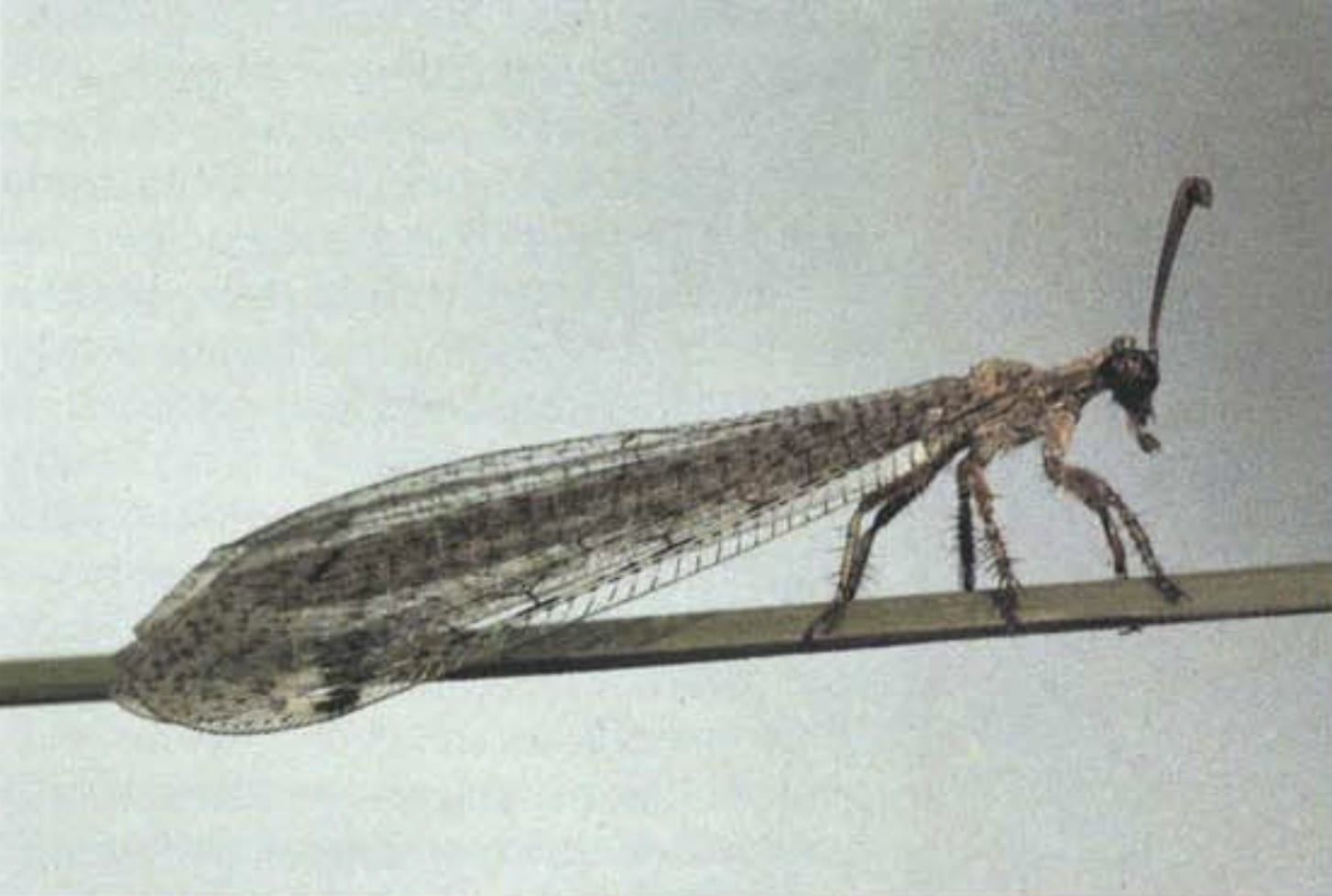

Adult ant-lions resemble dragonflies, with four narrow, transparent wings. The largest are as large as the biggest dragonfly, while the smallest are no more than a few centimeters across the wings. Unlike dragonflies, however, they settle with the wings folded neatly along the back, except when alarmed; then they raise all four wings together. Closer investigation will show that the head has two prominent, clubbed antennae just like a butterfly's.

Adult ant-lions are often attracted to light and are regular visitors to the walls of a well-lit veranda. Though their flight is rather weak and fluttering, it suffices to bring males and females together so that they can mate; indeed, at the adult stage, the ant-lion seems to have no other purpose in life.

Adult ant-lion

But why are they called ant-lions? Because, as larvae, the ant-lions are ferocious predators which feed almost exclusively on ants. Squat little creatures, with short legs, tough bodies and heads which carry impressive fangs, the ant-lion larvae live in soft sand where they trap ants in steep pits. With quick, powerful flicks of their heads and fangs, the ant-lion larvae throw sand, and even small stones, quite a long way, until the sides of the pit are so steep that ants stumble into them and slide to the bottom - where the ant-lions wait to seize them with powerful fangs.

Should the ant look as if it might to escape, the ant-lion has an extra trick up its sleeve. With the same sharp flicks of the head used for digging its trap, the ant-lion throws sand at the ant - forcing it to the bottom of the pit, where, once it is killed and sucked dry, it is unceremoniously thrown out of the pit just as quickly. How many ants an ant-lion eats as a larva is uncertain, but I am sure the number runs into the hundreds.

Since ant-lions live—literally—"in the pits," it's easy to spot them—not least because they usually live in little colonies in soft sand or dust; thus they are usually found in places sheltered from rain or excessive wind. Chances are that somewhere around any house in Arabia there will be ant-lions.

ant-lion pit

Ant-lions are particularly common in the dry zones of the world, and in their own modest way they are very successful. So successful, in fact, that it would have been strange if nature had allowed them to keep their hunting technique to themselves. And, as it happens, a small, obscure group of flies has developed the same technique, although the general shape of the fly larvae is very different. Probably the fly is also found in Arabia, though as yet there are no firm records.

The ant-lion's specialized and highly efficient life style is, of course, the result of evolution. The ant-lion, in fact, is a finely tuned result of a long evolutionary process that probably started with the largest of the Arabian species digging themselves into sand for protection while eating prey—and receiving an unexpected bonus. While digesting their previous prey, they would sometimes find additional victims accidentally stumbling into their pit. Since the pits provided food as well as protection, the ant-lions gradually developed the digging to the point where they no longer had to go hunting at all.

+++++++

Torben B. Larsen writes regularly for Aramco World on the entomology of the Arabian Peninsula.

You may also be interested in...

Abu Ali al-Hassan ibn al-Haytham's Optical Insights

Science & Nature

Joining math, physics and real-world tests, Abu 'Ali al-Hasan ibn al-Haytham, who worked in 10th-century Iraq, pioneered not only optics but also empirical science itself.

Spotlight on Photography: Orangutan Mother and Baby in Borneo

Arts

Science & Nature

For more than eight hours, we navigated the Sekonyer River in a wooden boat, cruising through Tanjung Puting National Park in the Central Kalimantan region of Borneo, Indonesia.

Can Fig Trees Help Us Adapt to a Changing Climate?

Science & Nature

Tunisia, where figs are one of the signature crops, has been an integral part of a just-concluded Mediterranean research project, FIGGEN, to assess how the trees thrive while climate changes are causing other crops to fail. For nearly four years scientists have worked to identify specific genetic traits that enable figs’ resilience and which varieties cope best with heat and drought. When FIGGEN publishes the results, farmers concerned for their future livelihoods may choose to grow the most promising types. Additionally, the study aims to plant a seed for preserving the biodiversity of increasingly arid ecosystems.