Trace Moruga Hill Rice's Cultural Path to Trinidad

Moruga hill rice is a nutritious dry-land red rice grown in Trinidad whose history dates to Merikin settlers.

Rising every day before dawn, Trinidadian farmer Mark Forgenie prepares himself to go into the “hole”—the forested area in the town of Moruga where he grows a unique variety of rice from West Africa. Red upland rice, or “hill rice,” as it’s also known, arrived on the island two centuries ago with Forgenie’s ancestors, formerly enslaved people from the Carolinas in the American South. Trinidad is, today, one of the only sites of its cultivation.

“My grandmother had three or four small plots behind her house [for] growing hill rice that she milled herself,” said Forgenie, whose commissioned studies found it contains high amounts of fiber, protein, iron and even vitamin C, which is not normally found in rice. “Between that, 5 acres growing other food and hunting bushmeat, she raised up 14 children. I remember being told that the hill rice alone was the most nutritious thing you could eat.”

Forgenie a merchant navy captain, remembers eating his family-grown and -milled rice. Inspired by local lore that rice had curative properties, he began farming and selling it internationally under the name Moruga Hill Rice in 2016. It was only mass produced once before, during World War II, when the British government used it to feed its troops.

Beyond nutrition, hill rice boasts another, less quantifiable value: It stands as a powerful example of cultural heritage that connects those islanders who grow and eat it today to the customs, foods, language and religion—including Islam—of their forebears.

Mark Forgenie, a descendant of those men, has been growing the rice in the Moruga Hill region of Trinidad since he was a child. Today, he sells it internationally under the name Moruga Hill Rice. (Courtesy Mark Forge)

British naval records tell us that Forgenie's ancestors arrived in Trinidad during the high heat of August 1816, along with 700 British Colonial Marines. The climate, like the wetland-dotted landscape, would have felt similar to their former homes in the American South. Also familiar would have been the presence of African people, enslaved as they had once been.

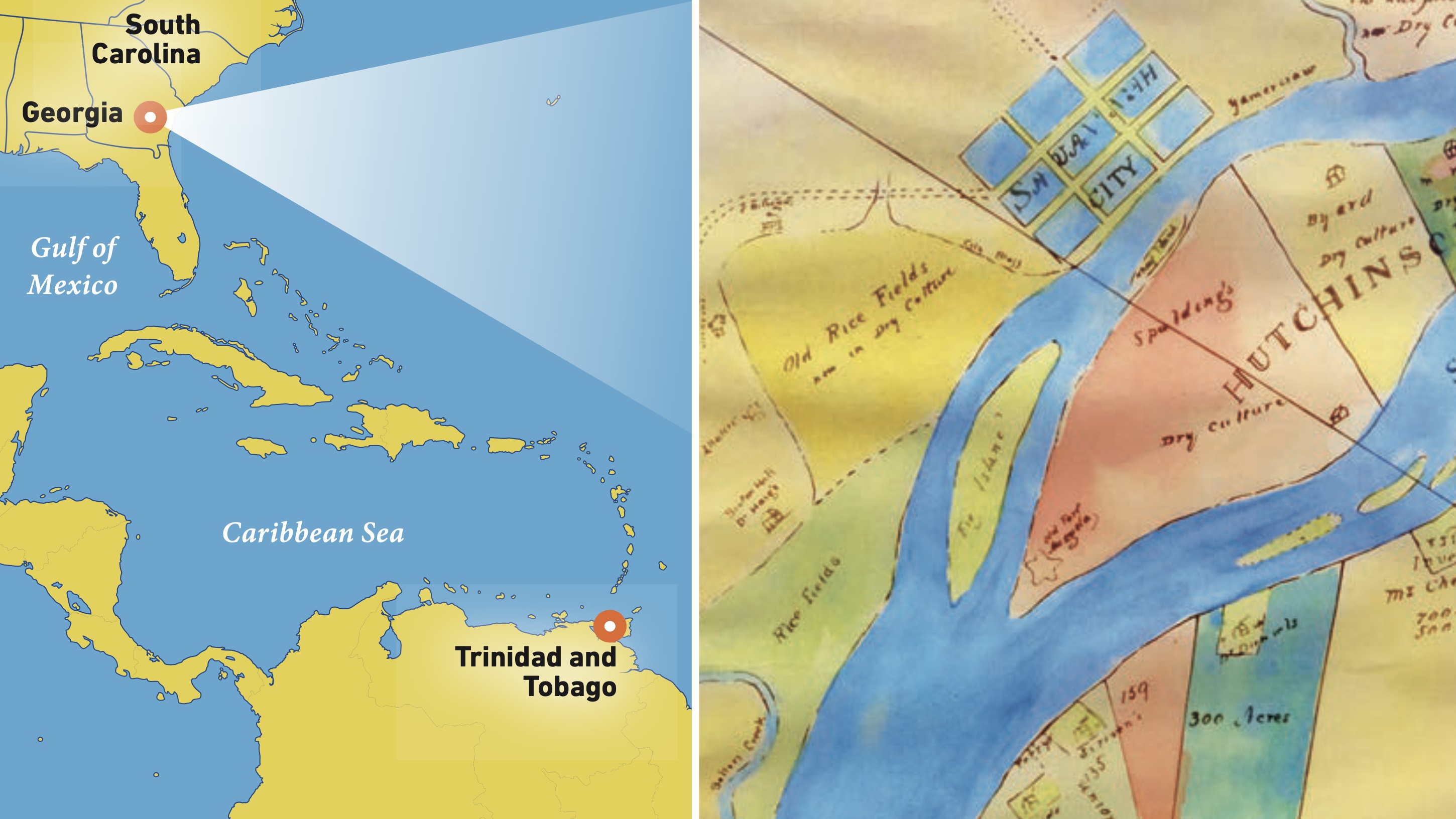

According to the US National Park Service, they hailed from the Chesapeake in the Mid-Atlantic region to the Carolinas and Georgia from a tight necklace of small barrier islands hugging the shoreline of America's rice country. Today the descendants of such enslaved Africans from this region continue to be called Gullah Geechee, a group whose dialects and culture have largely been preserved. Some weeks before they departed from the largest among them: Cumberland Island in Georgia, today a designated national seashore inhabited only by wild horses, alligators and deer.

The men fought with the British during the War of 1812 between Great Britain and the United States in return for freedom and crown land in Trinidad, then a British colony ultimately settling in Moruga in the south. They carried few belongings, among them tiny seeds of a unique red rice that grew on dry land.

In Trinidad, they were called Merikins—pidgin for "Americans." Like their forebears who were captured from West Africa's Rice Coast and enslaved in the American South almost a century and a half earlier, they were expert rice farmers. The rice they brought was "red bearded upland rice," or "hill rice," and it kept them alive, along with the help of the indigenous Warao people who showed them where to hunt and fish.

Hill rice connects those who grow and eat it today to the customs, foods, language and religion of their forebears.

Hill rice used to grow in the fields adjacent to the Cape Fear River, seen in the distance, in the Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson State Historic Site in Winnabow, North Carolina.

Upland Rice Growing Unchanged

Forgenie plants hill rice among trees on high ground. It is watered only by rainfall, as it still is in parts of West Africa today, according to Marguerite Agard, an Ashante princess and great-granddaughter of Ghana's King Prempeh I. She lived in Ghana until she was 8 before returning to the island with her Trinidadian mother. Known by her title Nana Abena, Agard recalls eating dryland rice in Ghana before experiencing it in Trinidad.

"It never occurred to me that it was special or different because it was both there and here," she said.

The manner of growing upland rice is dramatically different from that of the Carolina rice paddies in which Forgenie's ancestors labored, the vestiges of which still scar the low-country landscape. Satellite images available on Google Earth show the hard angles of irrigation ditches cut by enslaved people, according to historian Jim McKee, the site manager at North Carolina's Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson, a major 18th-century port and now a state historic site.

McKee said that the first Carolina rice was a West African white variety that grew as far north as Brunswick Town. He said these original varieties adapted to local soil and eventually became Carolina Gold, the prized variety that built vast fortunes for planters whose operations were particularly lethal.

"Working in rice fields was deadly business," said McKee. "There were alligators, malaria and yellow fever, but those dangers also kept White planters away. And that led to preservation of culture."

In an albumen silver print mounted to a stereographic card, photographer O. Pierre Havens shows upland rice being grown and harvested in the 1880s in Savannah, Georgia. (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

Rice and the Slave Trade

Like all stories of the Atlantic slave trade, the story of rice in the Americas is complex. A variety of West African rice (oryza glaberrima) was first planted in South Carolina in 1685 on dry land until flooding the fields produced greater yields. This was achieved through a system of floodgates and canals built with African know-how.

Historical evidence indicates that Portuguese slave traders witnessed rice growing prolifically in West Africa and purchased the grain to feed their human cargo. In 1594 trader and writer André Alvares d'Almada wrote a description of rice fields along the Guinea Coast, noting that the rice was started in inundated fields, then moved to drier land. Inland or "up land" variants of wild rice (oryza barthi) grew in forested areas—just as Forgenie plants Moruga hill rice. In 1678 the Anglo Irish botanist Sir Hans Sloane observed rice growing in the provision plots of enslaved people in Jamaica.

According to the International African American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, people from Africa's Rice Coast of modern-day Senegal, Gambia, Sierra Leone and Guinea were forcibly transported to develop what would become the American Rice Coast from North Carolina to Florida in the 17th century.

Jim McKee, site manager at the Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson State Historic Site along North Carolina's southern coast, shows how a traditional rice trunk irrigated fields.

Due to the harsh environmental conditions that planters themselves avoided, enslaved rice farmers were left largely to themselves. This allowed for the preservation of several aspects of West African culture, including language, according to Gullah Geechee Muslims in America by Muhammad Fraser-Rahim. Their local dialect remains remarkably like English vernaculars in the Caribbean where people of African descent, including Trinidad's Merikans, far outnumbered European planters.

Rice was a calorically dense staple for enslaved people that they could grow in subsistence gardens. Although encouraged by enslavers to raise their own food to reduce upkeep costs, it's unlikely that valuable paddy land was given for this purpose. The West African dryland variety fit the bill.

But historian David Shields, distinguished professor emeritus at the University of South Carolina, said the red bearded upland rice variety—Moruga hill rice—can be traced to Thomas Jefferson, who sought West African dry land rice to replace "swamp rice," which, he wrote, "sows life and death with almost equal hand." In 1790, while serving as secretary of state in Philadelphia, Jefferson received a 30-gallon cask labeled "red rice" that he distributed to planter friends including James Madison and very likely George Washington.

A historical map of rice planting in Savannah, Georgia, shows former rice fields along the Savannah River.

Even with such a famous booster, red upland rice didn't catch on among the Carolina planters for commercial use. But it did thrive among enslaved people and planters alike, who grew it for their own kitchens. Jefferson wrote in 1808 that it had been "carried into the upper hilly parts of Georgia, it succeeded there perfectly, has spread over the country, and is now commonly cultivated: still however, for family use chiefly." In 1830 Anne Newport Royall, widely considered the first female American journalist, saw it growing in Alabama: "Upland rice grows here with success. It looks like oats, is sown in drills, and plowed and hoed like corn. It is of a reddish color when cooked. Every planter rears enough for his own use."

Shields said evidence of hill rice appears within six years of the Merikin arrival in Trinidad. He has no doubt that red bearded upland rice arrived with the Merikins along with other distinctly African-South Carolinian foods.

"In Trinidad, I saw benne variety [a type of sesame seed] and okra varieties that were identical to what is grown in the low country," said Shields, who is also the former chairperson of the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation. "There was a corn variety that looked close to a type of corn that is grown in the Southeast called Guinea Flint."

Left: Gullah Geechee chieftess Queen Quet Marquetta L. Goodwine traveled to Trinidad to view the rice fields planted by Merikins—whose ancestors were captured from West Africa's Rice Coast and brought to the American South before being freed and arriving in Trinidad. Right: Roosevelt Brownlee, a Gullah Geechee descendant and soul-food chef from Savannah, Georgia, is a local advocate of hill rice dishes.

Moruga Rice Today

In modern Gullah Geechee communities, connections to dryland rice may be all but gone, but the intertwined history of rice and slavery is clear. For Gullah chefs like Benjamin "BJ" Dennis, who studies the historical connections among Africa, the Caribbean and the rest of North America, red upland rice represents a connection among people who are now strangers but whose shared legacy is hard-wired into their DNA. For Dennis, hill rice offers a compelling way to recast a solemn history of enslavement into honoring ancestors instead.

"The Moruga hill rice is a clear through line in the preservation of West African cultural heritage," said Dennis, who sees connections in Trinidadian dishes like pelau and the Gullah perloo, a one-pot dish of rice and meat like West African jollof.

Others in the Gullah community also see the Merikins' connection to both Africa and their own people with red bearded upland rice threading seamlessly into the present. In 2016, chieftess of the Gullah Geechee nation Queen Quet Marquetta L. Goodwine traveled to Trinidad to view the Merikin rice fields and speak about the cultural ties between the two regions. She brought home to South Carolina a small sample of hill rice to grow in honor of her grandfather, who grew Carolina Gold on the land where she now lives.

"I never got to meet him," she said. "But I felt his spirit with me when my grains of rice came up. I was very proud of that moment."

American chef Chaz Brown of Philadelphia shares the story of hill rice through his Afro Caribbean cuisine, including in his preparation with beef oxtails.

The Moruga hill rice is a clear through line in the preservation of West African cultural heritage.

Gullah Chef Roosevelt Brownlee, who lives in Savannah, Georgia, first experienced red bearded upland rice at a symposium a few years ago. He's had success growing a sample of hill rice decoratively in planters. "I was surprised because I thought rice only grew in the water," said the chef, a Rastafarian who can mark his 80-plus-year life's stages with rice. As a little boy, Brownlee's job was to buy quarts of Carolina Gold rice from the Savannah market for his aunt, who cooked hot lunches for Black men who couldn't eat at segregated restaurants.

Chaz Brown, a chef with both Southern and Merikin roots, has made it a priority to re-evangelize Moruga hill rice in America at the highest culinary level "for the culture"—in other words, the preservation of African diasporic heritage.

"I'm obsessed with it—it's calling me," said Brown, who has cooked at prestigious restaurants and appeared on reality TV's "Top Chef" and "Around the World in 80 Plates."

Back in Trinidad, hill rice continues to gain popularity—even outside the Merikin community. But for those who are tied to those original Gullah Geechee men, the drive to grow and eat these precious grains goes deeper.

"It's a link to our roots," said Agard, referring to the connections in the African diaspora." "It's a signifier of our culture."

Hill Rice Recipes to Try

Adapted from Sweet Hands: Island Cooking from Trinidad & Tobago by Ramin Ganeshram

Moruga Hill Rice Pelau

Serves 6

- 1 cup dried pigeon peas, pinto beans, cow peas or black-eyed peas, or 1 (12-ounce) can of any

- 4 tablespoons coconut oil, divided

- 1 small onion, chopped

- 1 clove garlic, finely chopped

- 2 cups Moruga hill rice

- ¾ cup sugar (white or brown)

- 1 (3-pound) chicken, cut into 8 pieces, skin removed

- 2 teaspoons green seasoning (available in Caribbean markets)

- 2 teaspoons salt

- 1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

- 2 cups coconut milk

- 2 cups chicken stock

- 1 bay leaf

- ½ cup chopped parsley

- 1 sprig thyme

- 2 carrots, peeled and chopped

- 5 scallions, chopped (white and green parts)

- 2 cups (about 1 pound) cubed fresh calabaza or butternut squash

- 1 small whole Scotch bonnet chile

- ½ cup ketchup

- 1 tablespoon butter

Pelau is a traditional Trinidadian dish that is like one-pot rice dishes from the African diaspora, such as jollof rice or New Orleanian jambalaya. While other cultures that favor layered rice dishes were also present in Trinidad—the Spanish with their paella and North Indians with biriyani—pelau more closely resembles the dishes made in the low country rice-growing region of the American South, the heritage corridor of the Gullah Geechee people from whom the Merikins descend.

In texture and ingredients, pelau is amazingly like perloo, a well-known dish from the low country. It is also like the rice and bean dishes found throughout West Africa.

This version uses Moruga hill rice in a traditional Trinidadian pelau, which is historically made with long-grain white rice, like Carolina Gold, also from the low country. This version goes well with Leonis Olaoshun Roberts’ Benne Chutney.

Step 1. If using dried peas or beans, soak them overnight in 3 cups of water. Drain peas/beans. Bring 3 cups of fresh water to a boil in a saucepan and add the peas or beans. Simmer for 20 minutes, or until almost cooked. Drain and set aside. If using canned peas or beans, drain, rinse with cold water, drain again and set aside.

Step 2. Heat half of the coconut oil in a medium saucepan over medium-high heat. Add the onions and fry until translucent, about 4 to 5 minutes. Add the garlic and fry until light golden brown, about 1 minute more. Pour in the Moruga hill rice and toss well to coat. Cook for about 1 minute and remove from the heat. Set aside.

Step 3. Add the remaining coconut oil to a large Dutch oven or other heavy deep pot. Add the sugar and swirl; allow it to caramelize to a light brown, about 4 to 5 minutes.

Step 4. In a large bowl, mix the chicken, green seasoning, salt and black pepper and stir well to coat. Add the chicken to the caramelized sugar and mix well. Cook for about 2 to 3 minutes then lower the heat to medium and add the onion and garlic. Cook for 1 to 2 minutes, stirring constantly.

Step 5. Stir in the coconut milk, chicken stock, bay leaf, parsley, thyme, carrots and scallions. Add the rice. Cover and simmer over medium-low heat for 25 minutes.

Step 6. Add the prepared peas or beans, squash, Scotch bonnet chile, ketchup and butter. Cover and cook for 40 minutes more or until the rice is tender and the liquid is mostly absorbed.

Step 7. Remove the lid and fluff the rice. The rice should be very moist but not sticky. Remove bay leaf, thyme sprig and Scotch bonnet. Serve with Benne Seed Chutney as a condiment.

Leonis Olaoshun Roberts’ Benne Chutney

- 2 cups benne seeds

- 2 tablespoons canola or grapeseed oil

- 1 loosely packed cup shado beni (culantro) leaves, chopped roughly

- 6 garlic cloves

- 4 to 5 bird peppers, stems removed

- 2 teaspoons salt

Leonis Olaoshun Roberts benne-seed chutney is a common accompaniment to the hill rice grown by her ancestors and modern family members. Roberts is a Merikin descendant who lives on the land granted to her five-times great-grandfather George Elliott. Elliott had been enslaved in the American South, possibly a member of the Gullah Geechee Nation. Elliott gained his freedom and a land grant in Trinidad, in return for fighting with the British during the War of 1812 in the Third British Colonial Marine company.

This chutney was made with local benne seeds, a variety still found in West Africa as well as in the low country in the American South. The area, which spans the coastal region from North Carolina to Georgia, is home to the Gullah Geechee people, who are descendants of enslaved Africans forcibly brought to America for their specialized knowledge of growing rice.

Benne-seed chutney is eaten throughout Trinidad, where it is often attributed to East Indian indentured laborers; however, South Asian chutneys use sesame seeds that are similar to but not the same as benne. A benne chutney very similar to that made by Merikin descendants is still eaten in Western Africa. Benne seeds are widely used there in everything from drinks, foods, candy and for ceremonial purposes because it is believed to ward off evil.

Benne came to the Americas as part of the so-called “Columbian Exchange” of foods and captive people moved between the Eastern and Western hemispheres. This recipe calls for 4 to 5 bird peppers, a tiny chili that packs a wallop and is native to the Americas.

Step 1. Pour the benne seeds in a large skillet over medium-low heat and toast, mixing often until they become caramel-brown, about 8 to 10 minutes.

Step 2. Place the oil, shado beni, garlic cloves, bird peppers and salt in a large mortar.

Step 3. Add the hot benne seeds to the mortar and pound into a paste, pausing to stir the ingredients together once or twice. Alternatively, you can grind the ingredients in a food processor and pulse into a paste. If you choose to use a food processor, allow the toasted benne seeds to cool to just warm before processing.

Step 4. Use as a condiment served over food, especially hill rice. Chutney can be kept in the refrigerator for up to 3 weeks. The finished chutney may also be rolled into small balls, if desired, before refrigerating.

About the Author

Jean Paul Vellotti

Jean Paul Vellotti is a photographer whose work illustrated Sweet Hands and has appeared also in The New York Times, National Geographic Traveler, Caribbean Travel & Life, Islands and more.

Ramin Ganeshram

Ramin Ganeshram is an award-winning journalist and culinary historian focused on colonial and early-19th-century history of the United States and the Caribbean. She is also a professionally trained chef who has authored cookbooks including Sweet Hands: Island Cooking From Trinidad & Tobago and Saffron: A Global History and is working on various forthcoming books.

You may also be interested in...

Bengali Snack: Potato Chops Recipe

Food

The Bengalis are famous for their “chops,” or potato croquets eaten as snacks with tea.

Lebanese Dish: Cracked Wheat and Tomato Kibbeh Recipe

Food

Simply cooked line-caught fish with this beautiful tomato kibbeh. I don't know how you could top it.

A View of Our Global Food Chain Through George Steinmetz's Lens

Food

In his latest book, Feed the Planet, photographer George Steinmetz visits nearly every corner of the world to record diverse yet linked aspects of the global food chain—including aquaculture.