How South Africa Came to Popularize Luxury Mohair Fabric Globally

South Africa is the world’s largest producer of mohair, a fabric used in fine clothing. The textile tradition dates to the arrival of Angora goats from the Ottoman Empire in the 1800s.

Gizella Arendse sits with a quilting needle in hand threading mohair—a fiber produced from the hair of the Angora goat. She is one of 11 women artisans working for the family-run van Hasselt farm at the foot of the Swartberg Mountains in South Africa.

Mohair, as a fiber, is known for its sheen, durability and resilience. Once it’s woven into yarn, either by hand or high-end machine, it is in high demand, primarily from the luxury clothing market. But its durability and ability to hold color also makes it popular for things such as shawls and blankets.

Most of its making starts on goat farms like this one.

“We see the whole cycle from the studio,” says Arendse. “…The newborn kids who are so cute, the teenagers they become, the first time they get sheared, and then, here us ladies sit, working with the very fibers from those animals, making beautiful things…”

“There is nothing like it,” Gizella Arendse says of mohair.

For the artisans mohair is a passion. “I love mohair. There is nothing like it,” she continues as she wipes a bead of sweat from her brow. It’s hot and dry here in the Karoo, the region where most of the country’s Angora goats are farmed. In fact, the word karoo means “dry” in Khoi, the language of the Bushmen who first lived in these parts. Here, in this dryness, Angora goats flourish.

Today, South Africa is the world’s largest producer of mohair—making 54% of the world’s supply in 2023, according to Marco Coetzee of Mohair South Africa (MSA), the industry body that promotes, regulates and supports the sustainable production of mohair in South Africa.

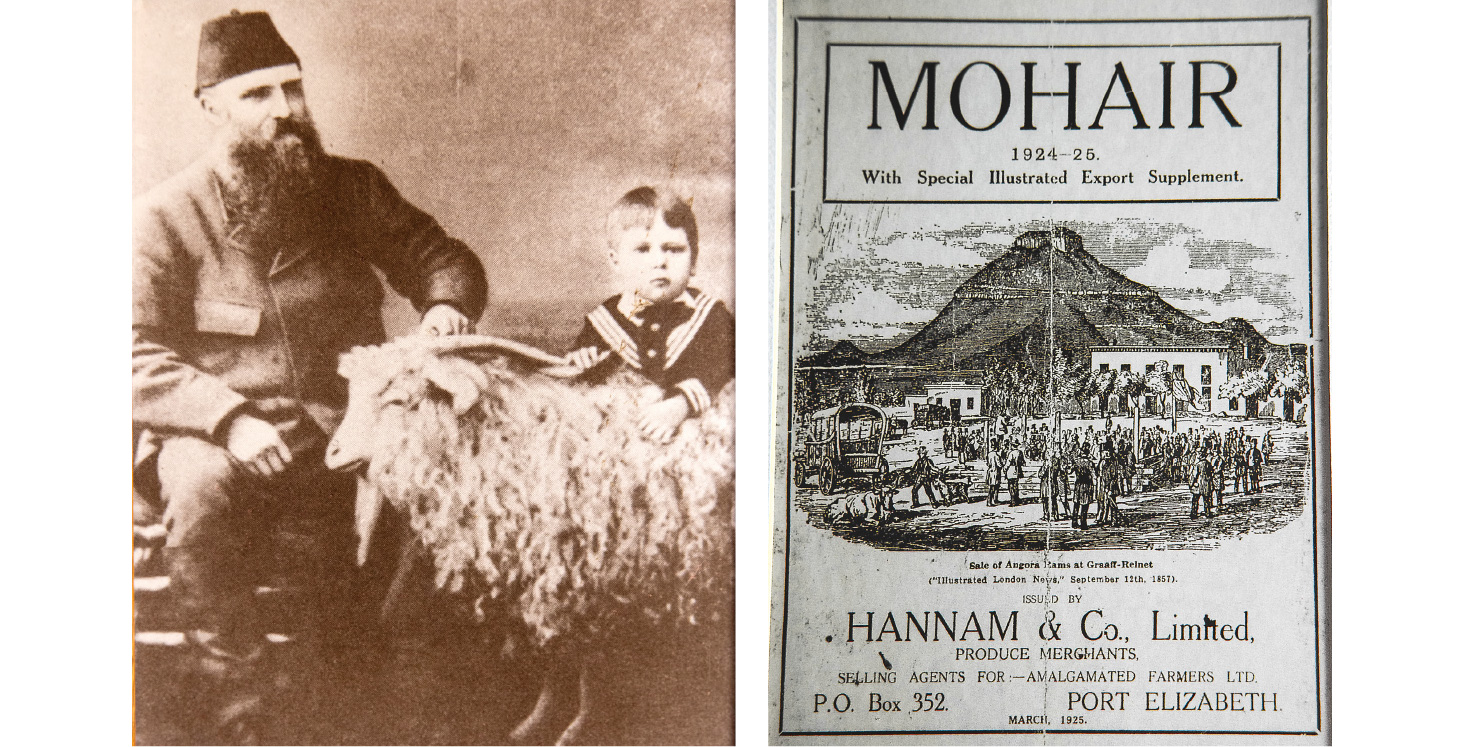

Yet mohair has not always been a major industry in South Africa. The first Angora goats arrived in the region, then a British colony, only in the 1830s. They were brought from the Ottoman Empire, specifically present-day Türkiye.

“The vibrant hues [mohair] produces are unparalleled in the textile world.”

Seda Ozbahar farms Angora goats in 2022 in Ankara, Türkiye, one of the world’s leading mohair producers. (Mehmet Ali Ozcan/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Mohair From Angora Goats of the Ottoman Empire

Goats in general have been around since time immemorial—they are referenced in holy books, and physical evidence shows they were present in Greek and Roman times. The exact origins of Angora goats, however, are somewhat shrouded in mystery.

Gürsel Dellal, director of Ankara University’s Ankara Goat and Mohair Application and Research Center, says the Angora goat is related to a breed that originated in the Himalayas and Tibet and likely came through migration of Turkic tribes from Central Asia to Anatolia in the 11th century CE.

In fact, he says, “it has been developed as a breed mainly in Ankara Province and its surroundings and takes its name from this city [formerly known as Angora].”

Left: John Brown and young Master Gatheral, son of the British consul to Türkiye, pose with an Angora ram in 1867. Right: The Mohair Experience Museum in Jansenville, South Africa, displays an old magazine cover related to the export of mohair.

By the first century CE, historical writings mention the distinctive long fiber of goats from Anatolia (Asia Minor). While this is not definitive proof of the breed’s origin, it suggests that selective breeding for long, luxurious locks began in this part of the world centuries ago.

In Türkiye the Angora goat was originally a house animal, kept by women to provide fiber for their own clothing. The goats, as we recognize them today, were first described in Western European writings, according to Dellal, as early as 1538.

The word “mohair,” he says, comes from the Arabic word mukhayyar. Originally meaning “distinguished” or “selected,” it came to refer to “goat’s hair fabric.”

Strict control of the industry allowed the Turks to dominate the mohair trade for centuries. While Angora goats became known outside the Ottoman Empire by the mid-16th century, it wasn’t until a hundred years later that raw mohair fiber reached Western Europe—partially because of a prohibition on its export, says Dellal.

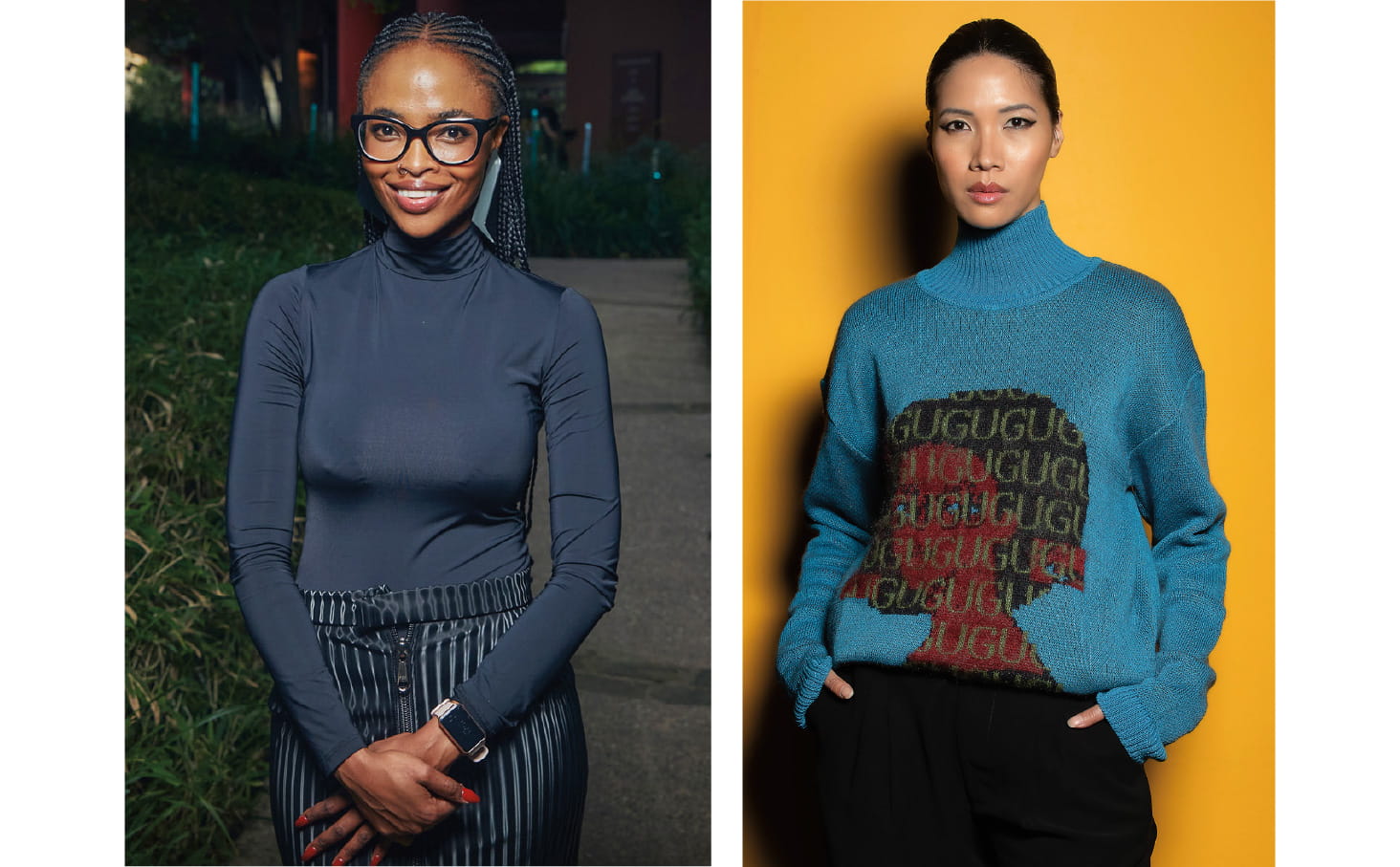

Left: With her GuguByGugu brand, fashion designer Gugu Peteni is elevating mohair onto the international stage. Right: A mohair sweater designed by Gugu celebrates her South African heritage and craftsmanship. (Courtesy of Gugu Peteni)

Domestic consumption and export of fabric woven from mohair fiber “made very important contributions to the Ottoman Empire economy for many years,” he says. In addition to the fabric, wigs, rugs, sweaters, hats, tablecloths, scarves and shawls were all fashioned from mohair, and all increased its recognition.

The prohibition on exports of the goats themselves was even more extreme. Dellal explains that in 1541 two Angora goats were sent to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V by Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. The next export didn’t come until the early 1800s.

In the late 1830s, the Ottomans gifted 12 infertile Angora rams and a single ewe to the South African officials. It’s here the story takes an interesting twist—the ewe was pregnant and gave birth to a ram kid during the journey, says MSA’s Coetzee.

The rest, as they say, is history. Over the following decades, more Angora goats were imported, and through selective breeding, farmers successfully established herds that thrived in the semi-arid Karoo region. By the mid-to-late 1800s, South Africa had surpassed the Ottomans in mohair production, becoming a dominant player in the global market. Fast-forward to 2024, and Mohair South Africa estimates that there are just shy of a million Angoras in the country.

Angora goats are raised on the van Hasselt family farm at the foot of the Swartberg mountains in South Africa. The farm owns one of the oldest mohair studs.

From Farm to High Fashion

South Africa’s thriving mohair industry—and the sheer scale of it—is palpable at the Stucken Group’s large processing warehouses and its Hinterveld Mill just outside Gqeberha, the country’s mohair hub. This family-owned, vertically integrated business has built its reputation over 150 years—first in Russia, then Germany and, since the 1950s, in South Africa.

A collection of colossal warehouses stores hundreds of bales of mohair bought at an auction. From here, the mohair is taken by forklift to several hefty machines, beginning an intricate process that turns the initially soiled fleece into finished fabric.

Hinterveld owner Daniel Stucken beams with pride as he explains each step, from shearing and washing to carding, dyeing and spinning. “It has a natural shine, like a diamond,” says Stucken—alluding to the fact that mohair is often referred to as the “diamond fiber”—“and diamonds are revered for their beauty and value.” He also believes that consumers are starting to understand the importance of slower, more sustainable fashion.

The culmination of the fiber’s transformation can be seen in Hinterveld’s showroom—a burst of color and texture. Mohair is known for taking dye exceptionally well, as Mandy Wait Erasmus, Hinterveld’s textile design coordinator, explains. “The vibrant hues it produces are unparalleled in the textile world. Designers, myself included, adore that facet of mohair,” she says.

It is these colors—and the fact that mohair is sustainably sourced—that South African designers are now embracing, taking the fabric from local farms to international catwalks, art biennales and high-end boutiques.

The Hinterveld Mill has operated since the 1950s, transforming raw fleece into dyed and spun fabric using sustainable practices.

One such designer who exemplifies this journey is Frances van Hasselt, who focuses on elevating mohair to a more prominent status as one of the world’s most ancient, exclusive fibers.

Having grown up on a family farm in the Karoo that owns one of the oldest mohair studs, she has always had a deep affinity for the fiber. “‘Farm to fabric’ is very much woven into my being,” she says. “For me our fabrics start with rainfall, the land, the health of animals, the care of a herdsman, the process of spinnluxury

ing yarn and finally weaving and finishing, the last few steps in a long line of codependent elements and actors that came before.”

She and her team—of which Arendse is one—weave stories into rugs, tapestries and capsule apparel collections, allowing the natural environment to inform every aspect of their design and manufacture. “We live in such a beautiful place. It’s so easy to be inspired by what we see around us here,” says Arendse.

South Africa has some of the best mohair in the world, produced under some of the most sustainable practices and in phenomenal processing houses. “Even though we don’t have a formal textile sector,” says van Hasselt, “we have thousands of highly skilled traditional textile artisans. When you combine the strengths and skills unique to South Africa’s textile ecosystem with excellent design and quality, we can produce products that can hold their own on any world stage.”

“The future of mohair in South Africa is a bright one.”

Left: Katriena Kammies, left, and Frances van Hasselt work on a loom to complete a tapestry installation titled “Threads.” With contributions from Kate Otten Architects, The Herd and van Hasselt’s studio, the piece was featured in the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale in Italy. Right Van Hasselt touts South Africa’s highly skilled traditional artisans.

Sustainability in high fashion

Another young South African woman who is hoisting mohair onto the international stage is Gugu Peteni. She is the creative force behind the brand GuguByGugu. Although the business just started in 2019, she already has fashion houses and fashionistas in a frenzy.

Inspired by and born in the ’90s, Peteni is bringing a fresh, bold look to luxury streetwear by adding an Afri-modern element to it. Knitwear, a cornerstone of her collections, reflects both her training and her South African identity. Her innovative mohair creations incorporate the fiber into contemporary fashion pieces that celebrate both heritage and craftsmanship.

Like that of van Hasselt, Peteni’s commitment extends to the sustainability of the fiber, its sourcing and production. Her studio strives to keep everything local.

A childhood of cutting up her mother’s tablecloths and curtains to make clothes for her dolls led Peteni to study fashion, ultimately landing an internship with MSA. “I love working with mohair; once you touch and feel it, you don’t really want to work with synthetics anymore.” Mohair became part of her brand’s DNA. “It’s more than a fiber,” she says. “It’s a legacy.”

Before 2020 Peteni was already making noise in the South African fashion world—presenting at the prestigious Design Indaba art gallery and participating as the youngest candidate in the “Project Runway South Africa” franchise. In 2020 her commitment to sustainability pushed her to create consciously made fashion pieces, which led her to represent South Africa at Lagos Fashion Week. The annual trade show in Nigeria is Africa’s largest fashion event, according to the government of South Africa.

Van Hasselt’s SOFA (Supporting Old Factories in Africa) collection consists of blankets, scarves and coats made from high-quality, end-of-the-run mohair yarn stock produced in legacy factories across the country.

From there the accolades continued flowing in. In 2024 her spring-summer collection titled “Echoes of Self”—which delves into the complexities of identity—showed at Paris Fashion Week and won the Best Young Designer Award.

She began a mentorship with fashion house Balenciaga. “This was a defining moment for me,” she recalls. “There’s a deep sense of pride in knowing that these pieces, made from locally sourced mohair and inspired by African heritage, are being appreciated by a global audience.” Her journey continued to New York Fashion week.

With collections that tell stories through textures and patterns, her work resonates deeply with those who value both innovation and tradition.

While South Africa now leads global mohair production, Türkiye remains one of the leading producers of the fiber in the world.

According to Dellal, the Angora goat remains of great importance to the textile industry in the country, as well as to folkloric culture, gastronomy and employment. The production of the fiber significantly increased over the past decade. He says his work at the research center aims to address and improve production of mohair because of more recent interest in organic textile products and therefore natural animal fibers.

Back in South Africa, van Hasselt says she feels inspired to be creating alongside peers who share her passion for craftmanship and local materials, and making them relevant, especially at a time when the world’s gaze is on South Africa and the rest of the continent. “The future of mohair in South Africa is a bright one,” she says.

Whether in Türkiye or South Africa, one thing remains undisputed: Mohair is truly the diamond fiber.