From Sultan’s Kitchen to Delhi’s Streets: Ni‘matnāma Lives On

A sultan’s 500-year-old cookbook still ripples across South Asia, from kitchens to street stalls to celebratory tables, preserving centuries of technique and taste.

Behind mahogany-finished cabinets and white-tiled walls, in the quiet order of a kitchen in Delhi's Noida neighborhood, chef Sadaf Hussain is bringing back recipes once served at a sultan's table. His deft fingers move in a choreography of their own as he shapes triangular parcels of paper-thin filo pastry, as if arranging folds of silk.

In under an hour, nearly two dozen samosas—sambusak or sambusa, as the savory fried pastries are known in parts of the Middle East and North Africa, respectively—stuffed with minced goat meat are fried to a crisp finish and piled high on a plate.

Hussain crafts each samosa from scratch, shaping and filling them according to a 500-year-old recipe within the pages of an illustrated cookery book, the Ni'matnāma, or Book of Delights (1495-1505). It was commissioned by Sultan Ghiyath Shah (also known as Ghiyas-ud-Din Shah, Ghiyasuddin or Sultan Ghiyasuddin Khalji), the maverick ruler of the Sultanate of Malwa in what is present-day Madhya Pradesh, India.

The chef's golden pastries—with their delicate folds, warmly spiced meat filling and crisp, deep-fried shell—emerge as they would have centuries ago, their flavors unchanged, timeless.

"The essence of the dish has remained remarkably the same," he says, breaking a samosa in his hands to show its perfectly cooked filling.

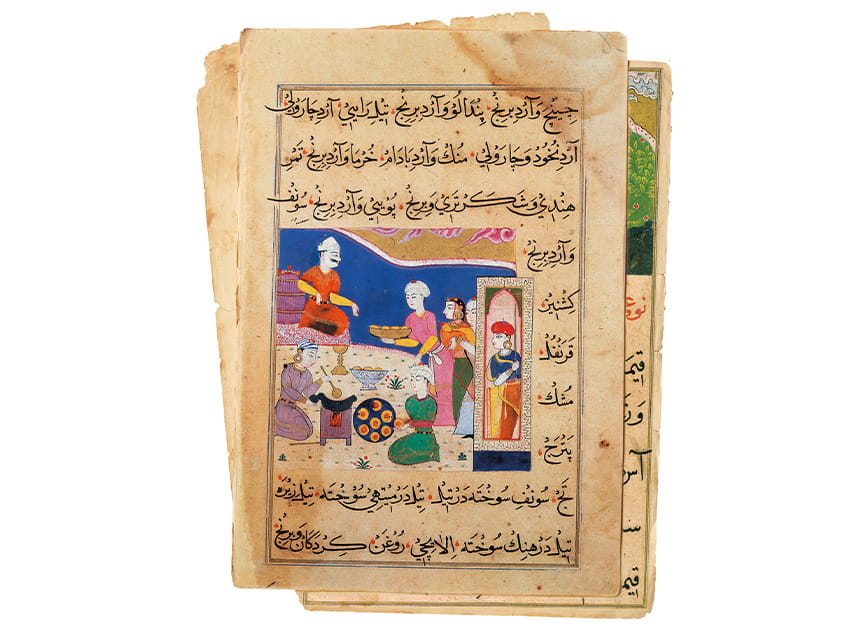

The Ni‘matnāma features the preparation and serving of samosas, sweets and other foods for Sultan Ghiyath Shah via both written recipes and opaque watercolors.

The British Library

The manuscript from which he works, a late-15th-century medieval book of recipes and illustrations, not only codified dishes still beloved today but also elevated cooking to a courtly art. Its influence continues to ripple across South Asia, from kitchens to street stalls to celebratory tables, preserving centuries of technique and taste.

The Ni'matnāma also contains early versions of other dishes still found on South Asian tables: semolina halva, the buttery dessert; khichdi, a textured mix of fenugreek-infused rice and lentils; and even qima, the lightly seasoned minced meat.

With the first batch of samosas already devoured—dipped into a rich imli chutney, a tangy date-tamarind sauce—only a few stray flakes of pastry lie on the counter. Hussain brushes them aside, a quiet reminder of the centuries-old recipe he has brought back to life.

Now carefully preparing another batch, Hussain demonstrates the original technique of filling the pastry with a generous spoonful of minced meat.

"I have adhered to most of the [original] ingredients. The recipe specifically asks for goat meat and four or five spices to enhance the natural flavor, not to overpower it. This, to me, is one of the most striking aspects; it isn't about masking the flavor with a heavy-handed approach to spices but letting the meat's essence shine through."

He notes one difference between the present and the past. Today samosas are often filled with aloo, or potato, a vegetable the Portuguese introduced to India in the 16th century—long after the Ni'matnāma was compiled. In Hussain's kitchen, however, the pastry still cradles the original minced meat, a direct link to the flavors of a sultan's table centuries ago.

"The Ni'matnāma is a bridge between medieval and contemporary cuisines," says Hussain, a consultant chef, Master Chef India finalist and most recently the author of Masalamandi, a book on Indian spices. "Its significance lies in providing an invaluable resource to the origins of these dishes and traditional cooking methods, some of which are still relevant."

“The Ni‘matnāma is a bridge between medieval and contemporary cuisines.”

Left: Chef Sadaf Hussain explains how to make khichdi, fenugreek-infused rice and lentils, an early version of which appears in the Ni’matnāma. In the foreground is a heap of red onions chopped and kept aside for the minced meat stuffing of samosas. Right: Plated recipes prepared from the cookbook.

The Ni'matnāma, a courtly cookbook

When Sultan Ghiyath Shah ascended the throne in 1469, he made a striking declaration: He would "open the door of peace and rest, and pleasure and enjoyment," according to contemporary chronicler Nizam al-Din Ahmed.

"During medieval times, rulers were considered ideal when they could balance strength with refinement," Rana Safvi, a historian of medieval and Mughal eras and author of several books on Delhi, says of Ghiyath Shah's unusual emphasis on cultural and culinary pursuits.

While his son Nasir assumed the day-to-day rule of the kingdom, Sultan Ghiyath Shah gathered chefs, musicians, poets, painters and bookmakers from across the world, many of whom were women. It was within this vibrant, unconventional court that the sultan turned his attention to food, commissioning a manuscript that would immortalize his tastes.

The sole surviving copy of the Ni'matnāma rests in the British Library in London. Written in bold Naksh—an elegant calligraphic style blending Persian and Urdu conventions—the manuscript features 50 jewel-toned miniature paintings, many showing Sultan Ghiyath Shah taking interest in food preparation.

"Visually rich manuscripts made culinary knowledge more portable to a largely nonliterate audience of courtiers and attendants," says Claire Chambers, professor of global literature at the University of York and co-editor of Forgotten Foods: Memories and Recipes from Muslim South Asia. "One could point to a dish or ingredient without having to read fine Persian script. Finally, these paintings preserve details of kitchen implements, dining rituals, even table layouts—visual data no pure recipe text could convey."

Left: Historian Rana Safvi says it was important for rulers in the sultan’s era to “balance strength with refinement.” Center: The use of spices, here on display at the Khari Baori wholesale spice market, remains largely the same as in the time before Mughal and Deccan courts. Right: A dry-fruit seller works amid Delhi’s bustling streets. Such fruits accompany milk cream in age-old specialties such as khoya samosa.

The Ni'matnāma goes beyond recipes, encompassing prescriptions and processes for making medicines, perfumes and aphrodisiacs, often with detailed directives for their use. The reader will detect a whimsy that reflects Ghiyath Shah's eccentric tastes, where food was not only nourishment but also play, spectacle and even jest.

Unlike modern cookbooks, the antique tome is not organized by recipe categories. A shorba (soup) could follow a sherbet, or a minced-meat dish could appear alongside a sweet. Perhaps this seemingly haphazard order reflects the whimsical nature of Ghiyath Shah's kitchen, a live record of dishes prepared according to the sultan's fancy—one day samosas, the next halva, the day after a gosht shorba (meat soup). Notably, the text gives hardly any specific measurements for the ingredients, suggesting it was intended for skilled hands familiar with the techniques.

"The real innovation of Ghiyath Shah and his son Nasir was, I think, institutional," adds Chambers. "They elevated cooking from an anonymous kitchen craft to a courtly art worth chronicling. By commissioning recipes and illustrations, they set a precedent that later Mughal and Deccan courts followed, creating a continuum of princely cookbooks."

Even without clear written instructions, the recipes endured. They slipped from parchment into kitchens, carried by memory more often than by manuscript.

From manuscript to street food

In Old Delhi's crowded lanes, where frying pans splutter and sweetshops spill their aromas into the street, the spirit of the Ni'matnāma lingers—even if most cooks and eaters have never heard its name. The markets serve as a living archive of samosas, puris (fried breads), halvas and the meat-and-rice dish known as biryani, each stall preserving a thread of culinary memory.

At Shyam Sweets in Chawri Bazaar, founded in 1910, fourth-generation confectioner Sanjay Agarwal continues his family's legacy, preparing the famed Nagori Halva—bite-sized, slightly sweet puris paired with semolina halva. "Our halva is always cooked in gentle heat," Agarwal says. "The temperature would not be more than what a couple of candles would emit."

A few lanes away, in Chitli Qabar, Zuhaib Hassan preserves his grandfather's recipes at Ameer Sweets.

Its samosas, both savory and sweet, are immensely popular. "Our minced-meat samosas are much loved, and during Ramadan it is one of our highest-selling items," Hassan says. "We also make our age-old speciality khoya samosa [stuffing of milk cream and dry fruits]. Every item we make today has been in our repertoire from my grandfather's era."

Left: Ever popular samosas and poori are quintessential breakfast items. Center: Markets serve as a living archive of Ni‘matnāma-inspired dishes including halvas, left, and bedmi puri. Right: Homemade halva from the Ni‘matnāma is cooked and served topped with nuts.

Khichdi and halva

Back in his Delhi kitchen, chef Hussain gathers handfuls of lentils and rice to prepare khichdi, a simple, comforting dish recorded in the manuscript.

"What we make at home has more rice and less lentils in proportion," Hussain notes, roasting the grains together before adding a few methi dana (fenugreek seeds) and a pinch of salt. "In the book the ratio is three parts lentil (moong dal) to one part rice."

Perceived as "food for the sick," khichdi is lightly spiced and easily digestible. Yet Hussain wonders whether "it really was considered sick food back then or if our perception of 'healthy meal' has shifted over time."

The result, he finds, is hearty enough for anyone. No surprise, he adds, that European travelers adopted the dish, transforming it into the Anglo Indian comfort food, kedgeree.

Now Hussain moves to a table in the corner to prepare ingredients for halva, a sweet beloved across South Asia with roots in the Arabic word halwa, which literally translates to "sweet." This version, he explains, is a multigrain halva, combining rice flour, roasted gram flour and whole wheat flour for a rich, layered texture.

"A surprising element [from the book] was the use of three sweetening agents in one dish: molasses, sugar and dates. I had never tasted halva made with molasses before, so this was a revelation," he says. "Apart from the absence of camphor and musk, which I replaced with meetha attar (a fragrant essence used in cooking), the structure, richness and flavor have been true to the spirit of the Ni'matnāma."

“Visually rich manuscripts made culinary knowledge more portable to a largely nonliterate audience.”

The traditions of the Ni‘matnāma live on in Old Delhi and across South Asia—even if most cooks and eaters have never heard its name.

For scholars too, the ancient book offers insights beyond flavor.

"Recipes are living documents," Chambers notes, reflecting on how the Ni'matnāma also captures trade routes, local and exotic ingredients and the networks of culture that shaped 15th-century Malwa.

With practiced hands, Hussain plates the final spoon of halva. "Techniques are timeless, but the soul of a dish lies in how it's prepared," he says. In his kitchen, the Ni'matnāma lives on, five centuries of culinary history still preserved and shared today.

More From AramcoWorld

After Courtly Feasts Came a Mango Empire

About the Author

Irfan Nabi

Irfan Nabi is an Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates-based photographer whose works have been featured in several books and global exhibitions, exploring themes of people, culture and food.

Nilosree Biswas

Based in Philadelphia and Mumbai, Nilosree Biswas is an author, filmmaker and columnist who writes about Asian history, art, culture, food and cinema. Her work regularly appears in national and international media.

You may also be interested in...

Recipe: Chickpeas for Breakfast: Try Punjabi Chole Masala Recipe

Food

Chole masala is a popular breakfast dish of chickpeas.

Artichokes to Ricotta: How Arab Rule Changed Sicilian Cuisine

Food

The cultivation methods, crops and dishes that Arabs introduced in Sicily not only survive but thrive today through foods that are integral and widely celebrated.

Biting Into the Past: Re-creating Gary Nabhan’s Albóndigas Meatball Recipe

Food

What do lamb, pomegranate and a Silk Road secret share? A meatball with a hidden past.