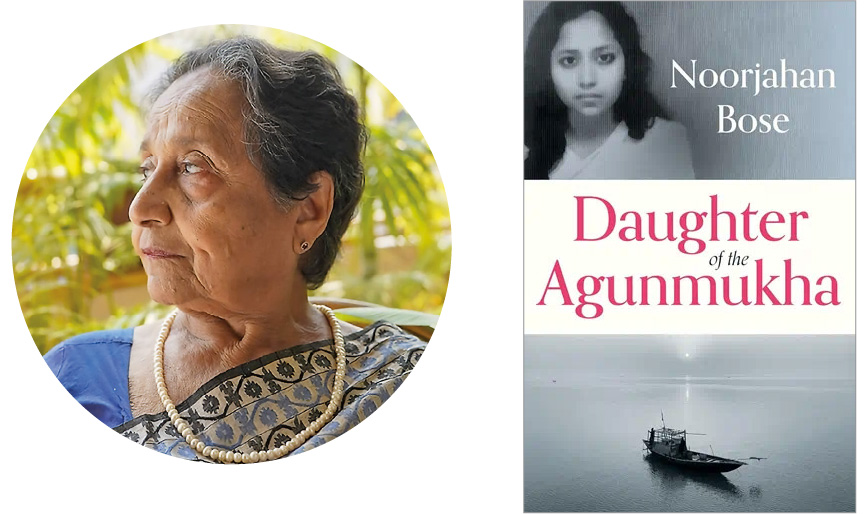

Noorjahan Bose was born in 1938 into a family of renowned cooks in Khatakhali, an island village on the southern coast of Bangladesh, yet her mother kept her out of the kitchen, insisting her eldest daughter pursue education instead. She earned degrees in literature and sociology—then taught herself to cook—building up a lifetime of intuition she’d later pour into her memoir, Daughter of Agunmukha.

When her daughter Monica Jahan Bose, who’d helped edit her mother’s memoir—sent me a recipe for shemai, the traditional vermicelli-based Bengali dessert, I thought of how, in the book, it carried the weight of nostalgia and wonderment but also defiance: the act of claiming one’s own story.

Shemai—like the machine-cut noodles made by that exiled thief’s wife in Bose’s memoir who returned to spin gossamer threads of dough and dreamlike tales from the Indian Ocean Andaman Islands, just east of the Bay of Bengal—seems simple on the surface: vermicelli toasted golden, simmered in spiced milk, studded with fruits and nuts. Yet it never presents as just food. It reflects a woman who once hunched under shame but now stands straight, her hands steady as an entire village leans in, disarmed by the alchemy of sugar and survival. Standing at my stove, I feel the weight of tradition, until I remember Bose’s unflinching words.

COURTESY OF NOORJAHAN BOSE

A Recipe of Choices

The origins of shemai trace to Bengal’s nawabs, or provincial governors, in the 16th to 18th century, but Bose’s version presents itself as a manifesto of adaptability. I toast the vermicelli. Can I swap in low-fat milk? Cardamom or cinnamon? Pistachios or almonds? All are fine, she says.

The flexibility unsettles me. In Pakistan and India, where the dessert seviyan, meaning “vermicelli” in Urdu, is served milky, its respective variants, qawami seviyan or meethi seviyan, or “sweet vermicelli,” is made dry. Meanwhile in Afghanistan, sheer khurma, Persian for “milk date,” dazzles with dates and nuts. How could something so cherished—a Mughal-era delicacy, an Eid-morning tradition with variations across South Asia—have no fixed formula?

“Make it your own,” Bose assures me. “If you want it very sweet, add some sugar, and if you prefer cinnamon to cardamom, go ahead and throw a cinnamon stick into the milk. The main thing is to make it what you want it to be.”

Ingredients

Shemai

Serves 1

- 200 grams package of shemai (thin vermicelli pasta)

- 2 liters whole milk or 2% milk

- 1 cup sugar

- 1 cardamom pod

- 1/3 cup raisins

- Handful of sliced pistachios or almonds (optional)

- 1/4 cup butter, ghee or olive oil (optional)

Making the Dessert

Step One: Prep

I begin by crushing the 200 grams of shemai noodles inside their plastic bag, pressing down until the brittle strands fracture into rough 1-inch pieces—just as Bose recommends—to avoid messy chopping.

Step Two: Toasting

The irregular fragments spill into my largest pan (she prefers a steel pot; I don’t own a suitable one). At medium heat, the noodles refuse to color, and my stirring grows anxious until I recall Bose’s pragmatism. After I increase the heat, the noodles begin to turn from yellow to a rich caramel color in less than a minute.

Step Three: Flavor

I pour in the 2 liters of cold milk—whole milk would make it creamier, but I choose low fat for lightness. The liquid erupts in furious bubbles as it hits the scorching pan.

Once the boiling subsides, I stir in a cup of sugar and spoonful of cardamom pods. Bose recommends using as much or as little cardamom as you like, noting that cinnamon also works. I nearly add both but hesitate, sticking to tradition this time.

Five minutes of simmering leaves the vermicelli tender but still firm—how I prefer it.

Step Four: Finishing Touches

I fold in a 1/3 cup of golden raisins (though regular would do) and a handful of pistachios I’ve chopped roughly. Remembering Bose’s caution that one is certain to mistake a green cardamom pod for a green nut, I fish out the spent spice before ladling some shemai into a bowl.

Against convention, I skip the fridge and eat it warm, garnished with extra nuts. The first bite is exactly what Bose promised: exactly right for me. After all, I’ve made it my own.

You may also be interested in...

Recipe: Chickpeas for Breakfast: Try Punjabi Chole Masala Recipe

Food

Chole masala is a popular breakfast dish of chickpeas.

Spicy Roasted Cauliflower Side Dish

Food

Ma’aleh is usually deep-fried cauliflower, served in a sandwich with raw vegetables and tarator.

Bengali Snack: Potato Chops Recipe

Food

The Bengalis are famous for their “chops,” or potato croquets eaten as snacks with tea.