Sisters Behind HUR Jewelry Aim To Honor Pakistani Traditions

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.

What began with a handmade pair of earrings exchanged between sisters in 2017 has evolved into a jewelry brand with pieces worn in more than 50 countries.

Three sisters from Pakistan—Hira, Hajra and Hina Hafeez-ur-Rehman—are behind HUR (recently renamed from Pierre Gemme by HUR), which blends history, craftsmanship and storytelling into wearable art.

From left, sisters Hira, Hina and Hajra Hafeez-ur-Rehman operate the global jewelry brand HUR. Top HUR artisans employ traditional South Asian techniques requiring "extraordinary precision," according to Hira.

Photographs courtesy of HUR

Residing in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Hira brings global perspective, partnerships and strategy; Hajra leads much of the brand's campaigns and narrative storytelling from Rome; and Hina guides design and oversees production from Lahore, Pakistan.

They maintain daily contact through calls and collaborate through online platforms.

Together they weave legacies of Mughal, Persian, Byzantine and South Asian artistry into contemporary jewelry that honors women's voices across history. At the heart of their work is a deep collaboration with artisans in Pakistan, a commitment to heritage and a drive to use jewelry pieces as conversation starters.

They have inherited their flair from their father, Hafeez-Ur-Rehman, a poet. His work was often difficult to read, sometimes morbid, but always threaded with hope. He signed his poems "Hur," a version of his initials, and carrying that forward is deeply meaningful for the sisters.

In this interview with AramcoWorld, Hira reflects on their beginnings, inspirations and the future of jewelry that connects past and present.

Left Signature Collection gold earrings carry influences of various cultures and eras. Right Mughal-era portraiture of women inspires some HUR pieces.

Hina made a pair of earrings that she sent to Hajra. How did that small gesture evolve into a global brand?

When we created that first piece, inspired by the Achaemenid dynasty from 550 BCE, we didn't realize how profound it was. It reminded us how jewelry has always carried stories and legacies. What inspired us most was the role of women in this history. We wanted to highlight that they were not silent figures; they were thinkers, leaders, creators. Through our designs, we try to bring their voices back to life. Our jewelry is less about ornamentation and more about conversation-between past and present, heritage and modernity, and the women who came before us and those who wear our pieces today.

How do you merge different histories into your designs?

Design is about finding the invisible threads that connect worlds. These eras may seem far apart, but they share a language of geometry, detail and symbolism. We love taking a Persian motif, a Mughal stone setting or a Byzantine pattern and letting them speak to each other. It feels less like borrowing and more like continuing a conversation across centuries. But inspiration doesn't only come from history. Our Apex collection was inspired by Pakistan's northern landscapes. Nature is an endless teacher. So are other art forms including painting, sculpture, even music. In the end, jewelry becomes a way of holding history, nature and imagination close to you.

Craftsmanship and heritage are central to your brand. How do you work with artisans to bring your designs to life?

It feels like a responsibility: to honor artisans in Pakistan whose skills are inherited through generations, to preserve traditions while reimagining them. We've been working with one artisan and his team in Lahore's Shah Alami market since the beginning. As we've grown, more young craftsmen have joined. Jewelry making here is male dominated; we tried hard to bring women into the process, but it has been challenging.

Many of our techniques are traditional South Asian ones-kundan, polki, meenakari and jali work. These require extraordinary precision, especially polki, where uncut stones are set into pure gold foil without prongs. We also draw on techniques we've learned while traveling. Our upcoming collection will incorporate methods from Egyptian artisans.

HUR jewelry is often described as a conversation starter. What do you mean by that?

Whenever we wear one of our pieces, people ask, "Who is this woman?" or, "What does this motif mean?" That's when a story begins. One example is a piece depicting a delicately rendered half-length portrait of a lady by 17th-century Mughal artist Kalyan Das, and suddenly we're talking about these enigmatic historical figures. There are not many named portraits of women from that era.

How do you decide which stories or figures to bring into your collections?

One of our favorite pieces is "Pursuit of Pleasure," inspired by that first Mughal painting of a woman [alone, rather than as part of a scene]. Until then most portraits were of men and their animals. For us it was momentous-a woman finally claiming space in art. That's the kind of story we feel compelled to tell. Another favorite is "Gulestan." It brings us back to childhood evenings when our father would introduce us to poetry, especially by [13th-century CE] Persian poet Saadi Shirazi. His "Gulestan" reminded us that humanity is interconnected beyond race, class or borders. Designing this piece felt like carving poetry into metal-something eternal, something that holds unity even in diversity. It reminds us that our design philosophy is a way of keeping humanity bound together.

How does your father's legacy continue to shape your journey?

When we sit down to write the stories, our inspiration often comes from reading our father's work. He set the bar so high-in the way he crafted his words, moved between layers of emotion and expressed both grief and joy. We recognize the patterns in how he built stories, how he said so much in such subtle ways. In that sense we do feel we are honoring him, though we also know we still have a long way to go before we can truly say we've done justice to his legacy.

We haven't yet published his poetry, but I hope one day his words can be worn, just as his spirit lives on in our storytelling. For now, every piece we create feels like an echo of his voice. And the brand's name was recently changed to just HUR.

How do you stay rooted in Pakistan while resonating globally, and what does it mean to see women worldwide wearing your work?

No matter where our inspirations come from, our jewelry is made in Pakistan, by artisans in Pakistan, led by three sisters from Pakistan. That can never change. We've realized that as individuals we have power. We aren't famous or influential, but stories shift the needle. That has always been our intention: to bring forward feminist stories, especially from the subcontinent.

Many women tell us our pieces make them feel seen, even the "smartest person in the room." That's powerful yet humbling. It shows that jewelry is more than an ornament-it's a vessel for connection, expression, even confidence.

You may also be interested in...

The Meaning of Henna and Its Rise in the West

Arts

The smell of eucalyptus and lavender oil mingles with the earthy aroma of henna paste lingering in the room. Jaya Robbins’s hands, already stained with henna on the tips, carefully pour a freshly made paste into a plastic pastry bag atop a large cup covered with a single pantyhose sock.

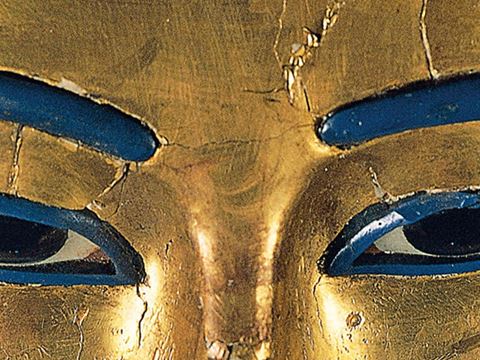

How Azza Fahmy's Jewelry Blends Egyptian History and Art

Arts

Azza Fahmy has become a legend in the world of artisanal jewelry from the Middle East. Her designs, now some of the most sought after in the Arab world and internationally, have long championed the history and culture of Egypt and the greater region with contemporary style, forms and vision—often with references to Pharaonic symbolism, Mamluk architecture, Egyptian modernism and vernacular cultures.

Pretty and Protective: Egyptian Kohl Eyeliner

History

Arts

Science & Nature

The black eyeliner known widely today as kohl was used much by both men and women in Egypt from around 2000 BCE—and not just for beauty or to invoke the the god Horus. It turns out kohl was also good for the health of the eyes, and the cosmetic’s manufacture relied on the world’s first known example of “wet chemistry”—the use of water to induce chemical reactions.