In Search of Ibn Battuta’s Melon

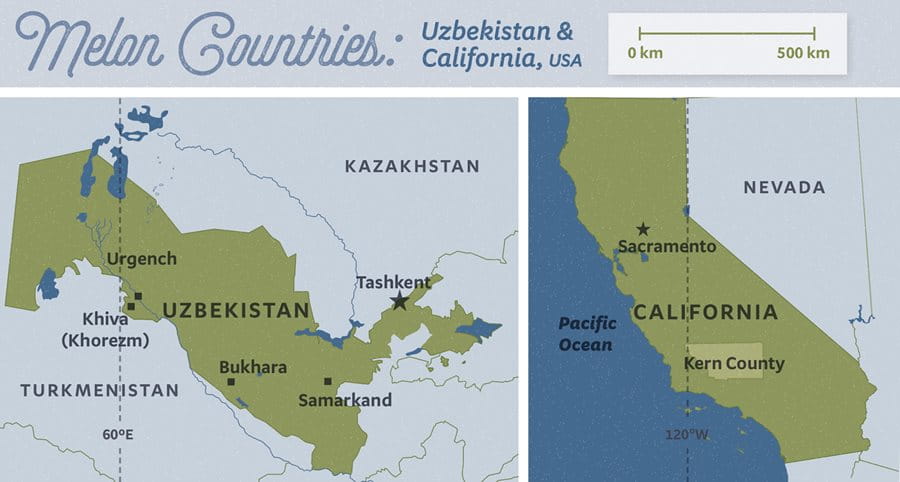

Peel of green, flesh of red and sweetness extreme, the 14th-century traveler’s five-star food review from Central Asia led, 681 years later, to a market-by-market journey, from a farmer’s field in California to melon stands along the road from Tashkent to Khorezm, Uzbekistan: Yes, Central Asian melons are that good.

On a bleak, dusty day in 1333, Ibn Battuta, the great traveler from Morocco, finally arrived at the Silk Road city of Urgench (which he called Khorezm) on the banks of the Amu Darya river. After the grueling 30-day march across the desert by camel-drawn wagons from Saraichiq, on the Ural River near the Caspian Sea, he wandered into a crowded market, and there he tasted the most delicious melon of all his travels.

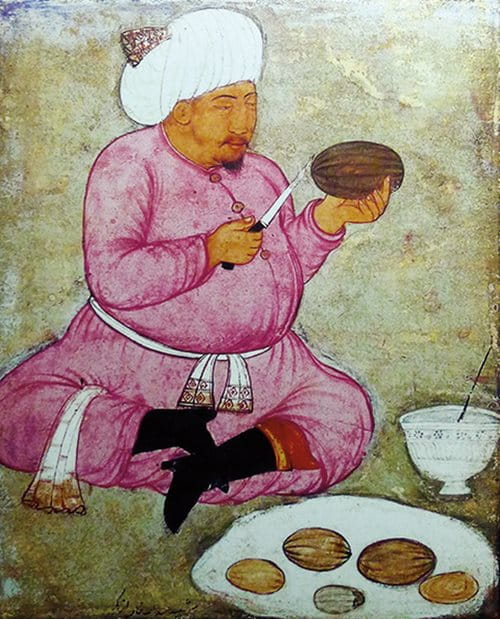

Painted in the late 16th century by an unknown artist, Abdullah Khan Uzbek ii, penultimate Shaybanid Khan of Bukhara, is shown slicing melons in his home.

Six hundred and eighty-one years later, I arrived in Urgench in early August after a bone-jarring, 12-hour drive by vintage, Russian-built Lada taxi from Bukhara across the forbidding wasteland of the Kyzyl-Kum (“Red Desert”). I had come in search of Ibn Batutta’s melon.

Cucumis melo, the sweet dessert melon that we know today, belongs to the family Cucurbitaceae—the gourd family, which also includes zucchini, pumpkins, squash and cucumbers. The sweet melons of Central Asia have a convoluted and complex history that continues to confound taxonomists and botanical experts. According to the book Melons of Uzbekistan, which was based on a scientific survey by the Uzbek Research Institute of Plants carried out in 2000, Cucumis melo is thought to have come from the sub-species agrestis Pang, a bitter, sour-tasting melon still found growing wild in Central Asia.

It is unclear exactly when sweet melons were first developed in Khorezm, an area encompassing much of modern Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and northern Iran, as well as ancient Persia, which included part of northeastern Iraq. These two areas are likely the source of all sweet melons grown throughout the world today.

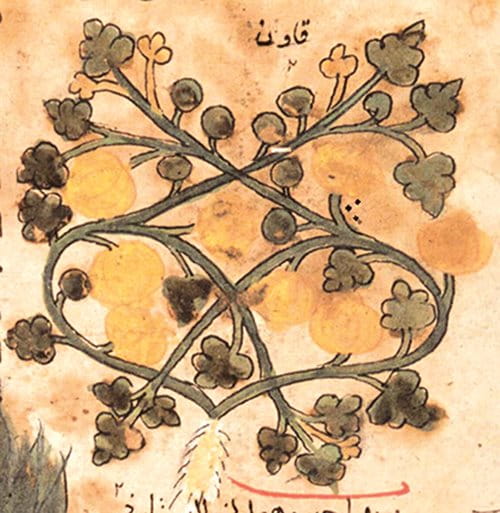

The earliest written mention of the sweet melons of Khorezm appears in Paradise of Wisdom, written in 850 ce by Ali ibn Sahl al-Tabari, who mentioned long, sweet melons in his chapter on vegetables. In the Arabic translation of Dioscorides’ first-century ce De Materia Medica (On Medical Matters) produced around 990 in Samarkand by Al-Husayn ibn Ibraim al-Natili, there is an illustration depicting the vines and ripe yellow fruit of Cucumis melo. The caption names it qawoun; in modern Uzbek, the word for sweet melon is qovun. Writing a bit earlier, in 955, Muhammad Abu al-Qasim ibn Hawqal, who traveled widely in Khorezm, described a long melon that was qabih al-mandar (ugly), but ghaya fi al-halawa (highest sweetness). He also mentioned that the melons were cut up, dried and “sent to numerous places in the world.”

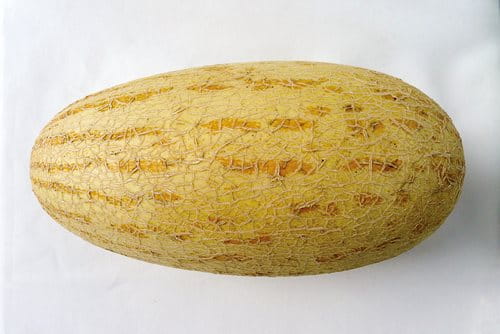

The varieties of Central Asian Cucumis melo that Mkrtchyan found adapted best to California’s soil and climate were Obinavat and Mirza, above left and right. At his melon stand at the Santa Monica Farmer’s Market, Mkrtchyan, below, helps restaurateur and celebrity chef Wolfgang Puck make a selection.

According to descriptions in the 11th century by Abu al-Khayr, sweet melon seeds, most likely of the casaba variety, made their way from Khorezm to al-Andalus around that time as a result of Islamic territorial expansion, trade and agricultural development. The seeds were conveyed along the maritime trade route linking the western Indian subcontinent to Egypt via the Red Sea and from there across the Mediterranean to Muslim Iberia—al-Andalus. Around the mid-15th century, Armenian merchants brought melon seeds overland to Italy. Sweet melons’ wild popularity there is evidenced by the fact that in 1471 Pope Paul ii died from eating too many of the sweet melons from the papal gardens of Cantalupo (from which we get the name “cantaloupe”).

In his 1895 book Travels in Central Asia, ethnologist and British spy Arminius Vambrey described the melon route from Khorezm east to China and northwest to St. Petersburg, in which melons were carried by caravans of 1,000 to 2,000 camels. Vambrey wrote:

....and fruits, the superior merit of which not Persia and Turkey alone, but even Europe itself, would find difficult to contest … but above all, to the incomparable and delicious melons, renowned as far as even in remote Pekin, so that the sovereign of the Celestial Empire never forgets, when presents flow to him from Chinese Tartary, to bring some Urkindji [Urgench] melons. Even in Russia they fetch a high price, for a load of winter melons exported thither brings in return a load of sugar.

Researchers have identified more than 160 varieties of melons in Uzbekistan, but no one had given much thought to exactly which one Ibn Battuta had described.

Captain Frederick Burnaby, in his 1876 book A Ride to Khiva, made similar observations:

Melon traders would shovel up snow and ice during winter and store it in deep underground cellars. Then in summer the most succulent melons were packed with ice and placed in large lead containers. These were then heaved onto camels to journey across the deserts to the banqueting tables of the Tsar of Russia, the Emperor of Peking and the Mogul rulers of Northern India.

Burnaby had the good fortune of tasting an aged Khorezm melon in the middle of a Khiva winter. “Anyone accustomed to this fruit in Europe,” he wrote, “would scarcely recognize its relationship with the delicate and highly perfumed melons of Khiva.” He added that “throughout the winter, melons are preserved according to an old method where they are put into straw or net bags and then hung from the ceiling of a special warehouse called a kaunkhana [qovunxona, or melon house].”

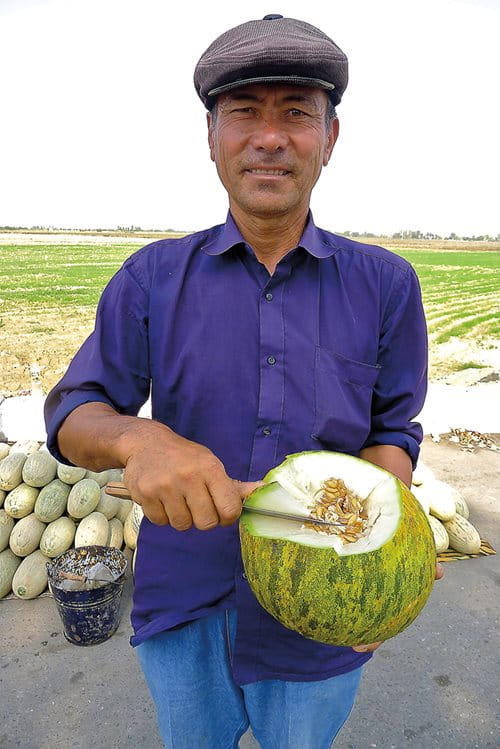

Along the road between Tashkent and Samarkand, melon salesman Mirza Baxodir offers passersby samples of one of his Obinavat melons at his stall at the Sirdaryo bazaar. “Anyone accustomed to this fruit in Europe,” wrote Capt. Frederick Burnaby in 1876, “would scarcely recognize its relationship with the delicate and highly perfumed melons of Khiva."

Today, Central Asia and in particular Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Iran and Turkmenistan (where Melon Day is a national holiday) are considered to grow the world’s best aromatic, sweet dessert melons. Of the older varieties, the Gurvak of Khorezm in Uzbekistan, the Gulobi of Turkmenistan, the Asqalan of northern Afghanistan and the Jharbezeh Mashadi from Iran are legendary among experts. The farmers of Uzbekistan, in the areas of Khorezm, Karakalpakstan, Bukhara, Samarkand, Tashkent, Surkhandarya, Kashkadarya, and Fergana Valley have been developing and improving sweet melons for thousands of years, and these types of melons are just now beginning to appear in specialty and ethnic grocery stores and farmer’s markets in California.

My journey to Khorezm started in Sacramento, California, when I paid a visit to Corti Brothers, a family-owned grocery store. There I found a towering pile of long, cream-colored melons called Mirza. They were priced at $2.50 a pound; other more conventional melons were selling for 25 to 60 cents a pound. I had never paid $22 for a melon, but I drove home with my purchase and, within two hours, had eaten the melon at a single sitting. The next morning I went back for more. The texture, taste, fragrance and melting sweetness of the luscious pale green flesh was like no melon I had ever eaten. It made me think of Ibn Battuta’s melon, and it made me wonder if it was still in cultivation.

Store owner Darrell Corti gave me the name of his Mirza melon supplier, and within a week I was in the high desert of Kern County, California, driving a rutted gravel road in search of Armenian immigrant and farmer Ruben Mkrtchyan, who had 1½ hectares of Uzbek melons under cultivation. After field trials of 28 different varieties in 2012, Mkrtchyan had settled on two: Obinavat and Mirza. Overripe or cosmetically flawed Mirza melons are sliced, sun dried and braided into a traditional Uzbek delicacy.

Mkrtchyan told me of his difficulties obtaining rare seeds from older varieties that are now starting to disappear. For example, he said, the seeds of one variety, the Jarbezeh Mashadi, which has been in continuous cultivation for 700 years, were smuggled from Iraq to France and then into the United States in the heel of a shoe (not his). Another variety, Battikh Samarra (melon of Samarra, a city in northern Iraq), goes back to the Abbasid Dynasty of the 11th century. (In Arabic, battikh can refer to either watermelons, Citrullus lanatus, or sweet melons, Cucumis melo.) When I heard the age of these two varieties, my idea to go in search of Ibn Batutta’s melon no longer seemed so far-fetched.

A month later, while visiting Mkrtchyan’s melon stall at the Santa Monica Farmer’s Market in Los Angeles, I fell into conversation with one of his first and most loyal customers: celebrity chef, restaurateur and philanthropist Wolfgang Puck, who was there to buy melons for his family. Puck was ecstatic about Uzbek melons, and he referred to Mkrtchyan as “The King of Melons.” Two weeks later I was on my way to Uzbekistan.

In Tashkent, I met Muhabbat Turdieva and Abdumalik Rustamov, co-authors of The Melons of Uzbekistan. Of the 160 varieties they described, there appeared to be several that matched Ibn Battuta’s description, but when I asked which exactly it might be, there was a long silence followed by a robust and lengthy professional debate over the numerous possibilities. Clearly no one had given much thought as to just which variety Ibn Battuta had described, or whether it was still under cultivation. There were almost too many to choose from.

Central Asian melons, they explained, are roughly divided into the following groups: Early ripening Khandalaks; early-summer, soft-pulp Bukharica and Gurvak; summer solid-pulp Amiri; summer and autumn-winter Cassabas and autumn-winter Zard. Many of the 160 varieties also had different common names according to regional dialects. One variety named after a certain breeder in one area might be known elsewhere by the distinctive color pattern on its rind, or even by an “expression of feelings.”

At lunch that day, Turdieva, whose title is forest genetic resources scientist, described her work assessing the distribution, diversity and conservation of local tree species, fruit crops and melons in Central Asia. Sustainable use of local varieties and conservation of their wild relatives are some of her special interests. During the melon expedition in 2000, she was involved with the survey of melon-growing areas, the study of farmers’ plots, the listing of melons grown and the description and collection of melon seeds from old varieties. In addition to cataloging melon varieties, her work aimed at “enhancement of the use of melon genetic resources.”

Uzbekistan’s melons enjoy their well-earned reputation for their unusual flavor and sweetness. Of the countries in the region, Uzbekistan has the largest amount of land devoted to melons. The total cultivated area comes to nearly 40,000 hectares of land, which yields approximately 450,000 - 500,000 tons of melons every year. Domestic consumption is high, and the largest export market is Russia. Turdieva expressed her concern about the loss of old melon varieties not only due to agribusiness pressures but also because generations of farmers and amateurs were no longer saving seeds the way they used to. To help protect the diversity of these historic and precious melon varieties, scientists now carry out regular seed-collecting expeditions and seed exchange programs to save these melon varieties for future generations of growers, breeders and researchers. To protect the old varieties, Uzbekistan now has one of the largest melon germplasm collections in the world with 1,330 accessions.

With only 12 days and an entire country to search, I had little time to waste. I contacted my friend Zafar Jahongirov, and that afternoon we began the melon hunt at Tashkent’s sprawling market, Chorsu bazaar. We sampled Mkrtchyan’s varieties— Obinavat and Mirza—and I found them as delicious as their California counterparts. We wandered into the cavernous dried fruit section, where I saw braided, dried melon and dried melon strips rolled up by hand, stuffed with large, seedless black raisins called Qorakishmish. The melon strips looked like caramelized dried apples, but that is where the similarity ended. Imagine the flavor of an entire, ripe melon, at the peak of perfection, concentrated into a single, chewy, toffee-like, melon-scented bite.

Marco Polo, in the late 13th century, had also sampled these: “They are preserved as follows: a melon is sliced, just as we do with pumpkin, then these slices are rolled and dried in the sun, and finally they are sent for sale to other countries, where they are in great demand for they are as sweet as honey.”

Jahongirov explained that autumn and winter melons of the Zard variety are still hung up to slowly ripen in qovunxona, the traditional drying sheds (“melon house”) mentioned by Burnaby. Harvested as early as September, properly stored winter melons can last from two to eight months. The melons become sweeter and juicier with the passage of time as the starches gradually convert to sugars until they attain a complex musky, perfumed melon flavor. After exploring the markets of Tashkent, we hit the road, stopping at every roadside stall, market place and melon shop along the way to Urgench, 1,119 kilometers down the road.

One was nicknamed The Dog’s Head; another, Flower-Water; yet another, The Queen Mother.

“Tatip ko’ring! Tatip ko’ring!” (“Taste it! Taste it!”) cried out the vendors at every stop, generously cutting samples from their best and offering them to us on the tip of a knife. We tried Kampir Qovun, known as “Old Lady melon” because it is wrinkled on the outside but sweet on the inside. We caught the very end of the season for Gurvak, which seems to be most people’s favorite. We sampled Andarxon, a fall and early winter melon; the Bishagi, which means “formless” because the melon comes in an assortment of shapes, and another favorite, Oq Novvot (White Sugar). There was a wrinkled, canary-yellow melon called Tirshek that is eaten fresh or hung up to age over the winter months. Many of the melons were not even among the 160 listed in Melons of Uzbekistan. One was nicknamed The Dog’s Head; another, Flower-Water; and yet another, The Queen Mother.

I asked many of the melon growers and their customers if they had heard of Dioscorides’ first-century ce advice to place a hollowed-out melon rind on the head of a child to bring down a fever or as a treatment for heat stroke. No one had heard of this, but all laughed and agreed a melon-rind helmet would be an excellent idea for anyone in the heat of an Uzbek summer.

After nearly two weeks on the road sampling dozens of melons each day, I finally arrived in Khorezm province at the well-known roadside Beruni melon market, near the banks of the Amu Darya river—very close to where Ibn Battuta tasted the best melon of his life. At the market, I met a kind, elderly, white-haired melon vendor by the name of Gulistan (Land of Flowers) and her two grandsons. Like most melon growers I encountered, she knew the story of Ibn Battuta’s melon, and she soon set her mind to deciding which variety it might be. As she mulled this over, I realized that in the previous two weeks I had not seen a single melon with a green rind and red flesh. I was beginning to wonder if Ibn Battuta had described a watermelon, Citrullus lanatus.

At Chorsu bazaar, Tashkent, dried and rolled melon, called qovun qoqi in Uzbek, is stuffed with black raisins (Qorakishmish) and walnuts.

A Tirshek melon in Khorezm province is tied and ready to be aged over the winter in a traditional qovunxona, or melon-drying shed.

Gulistan dismissed my skepticism. She told me that it sounded like Ibn Battuta was describing a late-summer melon such as an orange-fleshed Gurvak, or the light reddish-fleshed Ichi-qizil (“red-core”), or possibly a long-ripening winter melon of the Zard variety. Unconvinced, I continued my search.

That evening, I sent a hasty email to my friend Tim Mackintosh-Smith, the Oxford-educated Arabist, writer and lecturer who lives in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. Mackintosh-Smith is the author of an award-winning book and BBC trilogy in which he followed in the footsteps of Ibn Battuta, and he is arguably one of the foremost scholars on all aspects of Ibn Battuta. I mentioned the passage in the Gibb translation of Ibn Battuta’s rihla, or account of his journeys, that described the Khorezmian melon with the green rind and the crisp red flesh.

The earliest known depiction of Cucumis melo, or sweet melon, is in an Arabic translation, produced around 990 in Samarkand by Al-Husayn ibn Ibraim al-Natili, of Dioscorides’ first-century De Materia Medica (On Medical Matters). The word at the top transliterates as qawoun: The modern Uzbek word for sweet melon is quvon.

Mackintosh-Smith wrote back: “IB’s Arabic word is ahmar which can indeed be plain ‘red’. But Arabic colours are notoriously slippery. Sometimes they have a ‘green’ donkey for sale in the donkey market behind my house, but I think it is a shade of what we would call grey. Poets often describe the skin of especially beautiful women as ‘green’. I am pretty sure that ahmar for IB would have covered anything from watery pastel pink to deep purple; and green could mean anything from the palest shade of lime green to the densest pine forest at midnight. And the precise time of year is also problematic because Ibn Battuta was notoriously vague about dates. He describes a frozen lake to the south of Urgench, so this would suggest he was describing a fall/winter melon.”

Taking all of this into consideration, I expanded my search to include all melons that might or might not have a vaguely greenish rind with a flesh possibly, but probably not, tinged with a light reddish orange—or something similar. We were running out of time, and I had to make my best guess.

At 3:30 a.m., two days before I left Uzbekistan, Zafar and I drove into a meandering and nameless open-air roadside melon market. The vendors were all asleep. We approached a stall with a large selection of the Ichi-qizil melons that Gulistan had mentioned. It wasn’t a winter melon, but in all other aspects it matched Ibn Battuta’s description in terms of taste, texture, color and region of origin.

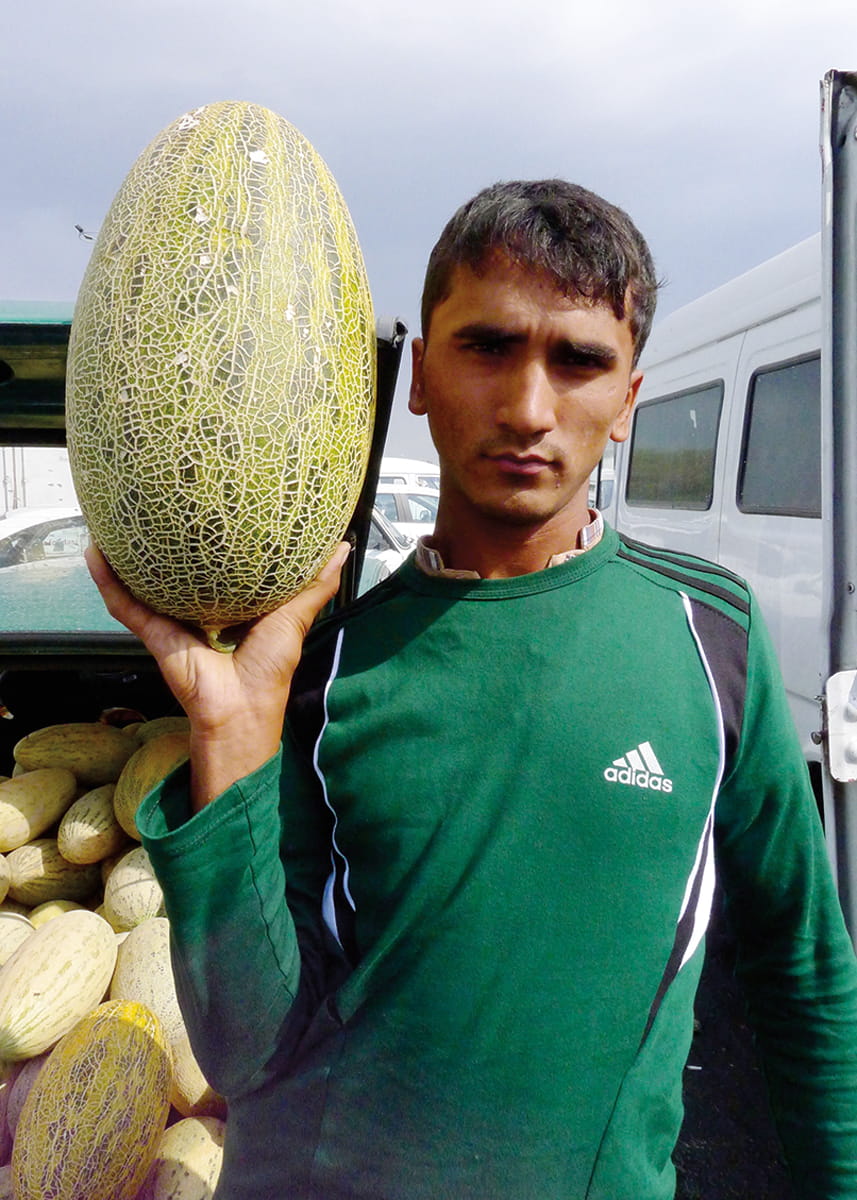

Holding an Ichi-qizil ("red-core") melon: Of all, it came closest to Ibn Battuta's description in taste, texture, color and region of origin.

Zafar woke the woman who ran the stall. She climbed from her wooden bed piled high with blankets and surrounded by a sea of hundreds of melons. Other nearby vendors were sleeping with their own melons. She turned on a single overhead bare light bulb. Zafar explained our long journey in search of Ibn Battuta’s melon.

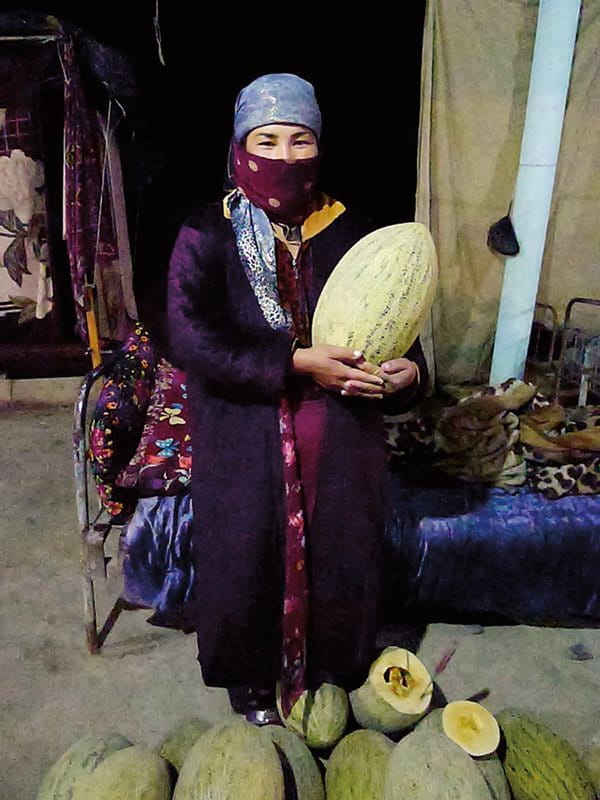

“Ibn Battuta’s melon, at this time of the night?” she laughed. Half asleep and wrapped in multiple layers of robes, she picked up an Ichi-qizil melon, cut samples for us and posed for a photo. She was flattered that of all the melons we had seen in Uzbekistan, we had selected hers.

In the closing hours of my quest, I realized that over the 681 years since Ibn Battuta’s visit to Khorezm, Uzbek farmers had been hard at work perfecting the art of melon breeding and growing. By saving old local melon seeds, creating and improving new varieties and passing down specialized horticultural practices according to regional water quality, soil types and climatic conditions, they had no doubt improved the disease resistance, shelf life, yield, texture, degree of sweetness and complexity of flavors of melons throughout the different growing areas. And then there was the issue of random variations due to natural hybridization in the melon fields to consider. With all of these factors in mind, it would not be surprising—even likely—that Ibn Battuta’s melon had evolved into something quite different, disappeared entirely, or simply fallen out of favor because other, more recent varieties were better.

Standing in the cold night air, one thing was clear: Ichi-qizil was as close as we were going to get. I paid for the melon, and the woman thanked us. She turned off the light and climbed back into her bed. We closed the car doors and drove into the night.

You may also be interested in...

From Sultan’s Kitchen to Delhi’s Streets: Ni‘matnāma Lives On

Food

A sultan’s 500-year-old cookbook still ripples across South Asia, from kitchens to street stalls to celebratory tables, preserving centuries of technique and taste.

AramcoWorld Explores Universal Food and Cross-Cultural Identity

Food

History

Muhalbiyat Al-Sagoo: A Fresh Spin on Sago and Lychee Pudding

Food

Obtained from the trunks of various palms, sago is used across Asia as a thickener for soups and stews and to make pudding. You can substitute other soft, sweet fruit like plums or pineapple, but the sweet juice of the lychee blends very well with milk. This is an exotic take on the traditional sago pudding popular in Gulf cuisine, made with sago, sugar and spices.