Epic Nation

The script could have been lifted from one of Central Asia’s traditional oral epics: A nomad woman spends her 97-year lifetime defending, ruling and ultimately uniting dozens of tribes, losing a husband and a son to enemies while laying the foundation for a nation. But it’s true: Kurmanjan was her name, and her country is Kyrgyzstan, where a new film tells her story to the world.

Does a legend make a film or does a film make a legend?

This was one of the questions I often asked myself as I followed the path of the film Kurmanjan Dakta: Queen of the Mountains and its historical heroine over one partly snowy, partly sweltering week in April across the Central Asian republic of Kyrgyzstan.

Born in 1811, Kurmanjan became datka (“righteous governor”) of several tribes in the Alai and Pamir mountain regions in 1865, a title she held until her death at age 97. She worked tirelessly to unite the region’s more than two dozen tribes amid regional and colonial threats that often set one against another.

One of the only photographs of Kurmanjan Datka was made by Finnish Colonel Carl Gustaf Mannerheim in 1906, when she was about 95.

At the heart of the film, which runs a bit over two hours, is a layered love story. On the one hand, Kurmanjan Datka fulfills the dream of intertribal unity promoted also by Alymbek, her second husband and predecessor as datka. On the other, it is a paean to Kyrgyzstan itself, a young nation formed in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The film’s panoramas hint at why Kyrgyz culture abounds with stories as epic as the land itself.

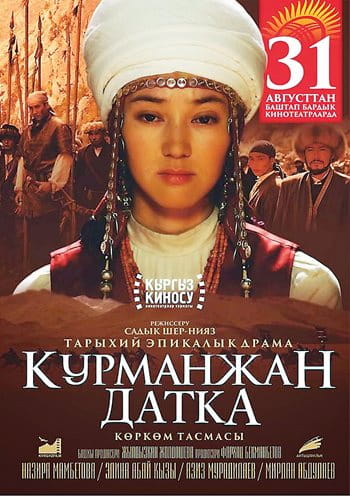

Released in 2014, Queen of the Mountains ran on three out of four Kyrgyz theater screens in its first month, and it kept running in many for up to six months, setting box-office records and becoming the highest-grossing Kyrgyz film to date. In 2014 Kyrgyzstan submitted the film for Oscar consideration. With a budget of about $1.5 million, it was also the most expensive film made to date in the country and the first to receive substantial government arts support.

Kurmanjan Datka: Queen of the Mountains, directed by Sadyk Sher-Niyaz, above, stars Elina Abai Kyzy, below, who portrays the early years of the historical 19th-century heroine remembered today as ulut enesi—mother of the nation.

In part due to a national reexamination of history following the Soviet era, Kurmanjan Datka’s historical story “became much more popular and relevant, but until recently it was not raised to the level of popularity that we had after the film,” says Elmira Kuchumkulova, professor of heritage and literature at the University of Central Asia in Bishkek, the capital. Like many, she went to see the film when it opened on Kyrgyzstan’s independence day, August 31. “Many people looked forward to it because they read about her in history textbooks, but they did not have a clear picture of her.”

The success has kept its director, Sadyk Sher-Niyaz, busy writing new scripts—in his spare time. A former minister of culture recently elected to parliament, Sher-Niyaz has an office in the White House, Kyrgyzstan’s seat of government in Bishkek. A career politician, he laughs and jokes fluidly the day we meet, whether it’s talking about politics or the film that consumed more than three years of his life. Working with co-writer Bakytbek Turdubaev, formerly of Al Jazeera, Sher-Niyaz notes that with all its vast scenes, the film required “around 10,000” people, “mostly as extras,” he says. “Doctors, teachers, a lot of theater people. It was a national collaboration.”

The idea for the film originated with another parliament member, and Sher-Niyaz was a natural to direct it: In 2007, aged 38, he had left his post as a deputy judge to study film in Moscow, a dream he had been unable to pursue as a struggling young father in the immediate post-Soviet era.

The film he made is reminiscent of classic American westerns, but replete with Central Asian culture and a female lead. Otherwise, the heroes (and especially the heroine) are selfless, the villains are conniving, the battles are drawn out for drama, and the horse chases switch into slow motion. Warring parties meet; landscapes dazzle and sweep. Like westerns, it’s a film that defines a history and builds a national narrative.

I ask Sher-Niyaz if American westerns inspired him. He professes the film he admires most is Mel Gibson’s Apocalypto, the gritty 2006 adventure set in coastal Mexico on the eve of Spanish colonialism. “He decided to shoot a historical film, which is very hard. You have to find out how they lived, how they ate, and so on. But Mel Gibson just decided how it was. And I respect that. I thought if Mel Gibson thought that, I also can decide how our people lived 200 years ago, no problem,” he explains.

If anything, this actually has been the film’s main problem. While in broad strokes Queen of the Mountains is accurate, in specifics it falls short now and then, according to historians. “Sadyk is a good, good man. But it is very important to us, part of us revising history, to be accurate,” says Tynchtykbek Chorotegin, the country’s leading national historian and a professor at the Kyrgyz National University.

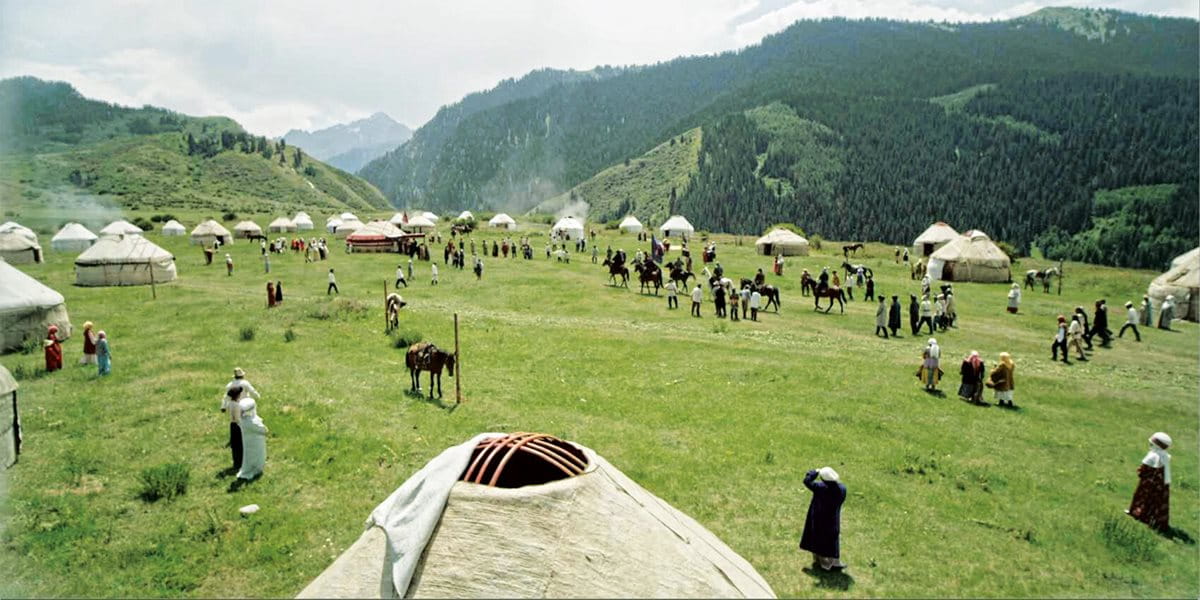

The film premiered internationally at the 2014 Montreal World Film Festival, where industry insiders and critics alike complimented its costumes and, as The Montreal Gazette noted, the “lush cinematography of the country’s mountainous landscape,” which appears here as a backdrop in a re-creation of a Kyrgyz tribal encampment.

He says that although he and others were invited to see the rough cut, it was too late for comments to take effect. Chorotegin notes that in some scenes, characters who were long dead in real history suddenly show up; in others, events that were not part of the culture take place. For example, a woman is saved from being stoned to death: This, he contends, is not a Kyrgyz tradition. “If a woman was unfaithful to her husband, their tribes would go to war, but the woman would not be stoned,” he says. “This is just silly.”

Just as silly, he points out, is Kurmanjan Datka writing a love letter in runic script. “The runic script was used by ethnic groups in some places until the 12th century,” he continues. “In the film, she was writing in [the] 1830s.”

But as this is all new history for Kyrgyzstan, few know the difference, and many who do regard the flaws as minor. The Kyrgyz are historically nomadic and have thus relied primarily on oral history for centuries and, among educated elites, Arabic script was still very much in use as recently as the late 1920s—well after Kyrgyzstan had been incorporated into the Soviet Union.

Proof of this becomes tangible in the village of Gulcha, 2,400 meters up the still-snowy Chyrchyk Pass from Kyrgyzstan’s second largest city, Osh. Gulcha was Kurmanjan Datka’s headquarters, the de facto capital of the Alai region she ruled. Sher-Niyaz says nearly everyone in Gulcha took part in the filming.

For many of them, it was a deeply personal experience. Of the more than 1,500 people in Kyrgyzstan who are considered to be descendants of the Alai queen, some 300 live in Gulcha. In 1991 Gulcha opened the Kurmanjan Datka Museum of History and Ethnography, a yurt-shaped building on the outskirts of the village that announces itself with a huge statue of Kurmanjan Datka.

Twenty-five students of tourism have just arrived from Bishkek, and they are being shown about by museum director Bazargul Koionbaeva, who, like the museum’s other five employees, is a descendant of the datka. As with politics and history, film works well with tourism, and the students are here to survey what their country has to offer. But it is hard to get here: Gulcha is a two-hour drive from Osh over precarious mountain passes and 12 hours from Bishkek. Before the film, the museum would have been little considered as a sightseeing destination.

Through gold teeth—a common feature of smiles here—Koionbaeva points out a letter penned by Kurmanjan Datka herself, in which her words in Kyrgyz use Arabic script. Koionbaeva refers to her as “our mother,” an endearing sentiment shared widely among Kyrgyz.

“We get about 15 to 30 visitors a day,” she says. “Since the film came out, we have gotten more visitors, even from other countries, especially representatives of ngos dealing with cultural heritage.”

Awaiting cues on location are co-stars Mirlan Abdylaev, center, who plays Kurmanjan’s younger brother, and Gulnur Asanova, right, who plays Asel, wife of Kurmanjan’s ill-fated son, Kamchybek. Asanova wears a traditional Kyrgyz headpiece called elechek, a rolled white cloth up to 30 meters long that could be used to wrap a woman’s body should she not survive a journey.

Most of the museum displays show traditional Kyrgyz clothes, weapons and utensils. But this is also one of the rare places you can see one of the only photographs ever taken of Kurmanjan Datka. Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, a Finnish member of the Russian army who later became Finland’s president, captured a handful of images at the end of her life.

A former history teacher, Koionbaeva also points out a rope: Donated by a family member, it is said to be the real instrument by which the Russians had hanged Kamchybek, Kurmanjan Datka’s son accused of killing the Russian soldiers who had disgraced his wife by cutting off her hair in search of a key to a box he refused to open. This set up the critical moment of Kurmanjan’s legacy: If she had stopped the execution, Kyrgyz widely believe the Russians would have utterly destroyed them; Kurmanjan’s sacrifice allowed her to negotiate autonomy that held the tribes together, and this is viewed today as the seed of nationhood.

Four actresses, each of a different age, play Kurmanjan: Last is Zhamal Seydakhmatova, above, whose acting career in Kyrgyz films spans seven decades.

Governor-General of Russian Turkestan Konstantin Kaufman’s expansion of Russian colonial power into the Alai Valley inspired resistance from Kyrgyz tribes under Kurmanjan; he is played by Victor Kostetskiy, a Russian actor with more than 100 credits to his name when he passed away months after the film’s release.

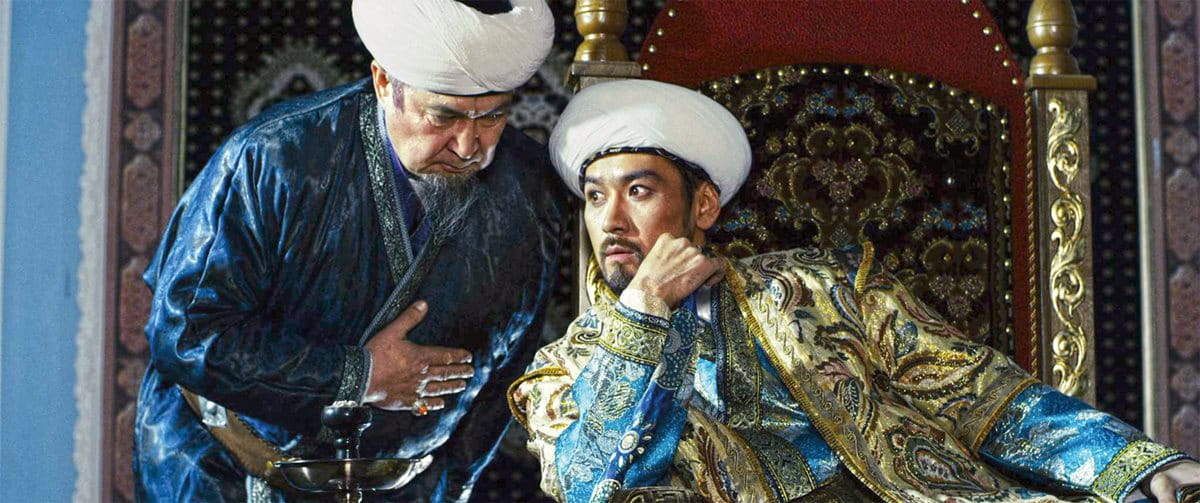

Threatened by the gathering power of Kyrgyz tribes to the east, Kudayar, the Khan of Kokand, played by veteran stage actor Jenish Smanov, ordered the assassination of Kurmanjan’s husband and predecessor, Alymbek Datka. Kurmanjan then determined to fulfill his vision of Kyrgyz unification.

Today she is remembered most of all for her assent in 1895 when Russian forces hanged her youngest son, Kamchybek, played by 25-year-old Adilet Usubaliyev. The heartbreaking sacrifice prevented what likely would have become the Russian annihilation of the Kyrgyz.

“I like working here,” Koionbaeva says. “Her spirit is still somewhere here helping people.”

Leaving Gulcha back to Osh, driver Dinara, translator Alina and I stop in a seemingly nameless village in the municipality of Mady. Dinara is pretty sure that somewhere in this area is a village named Kurmanjan Datka. There are no signs; streets are empty. We walk past a Soviet statue into the mostly deserted municipality building. We find Jumagul Esenova, Mady’s deputy head of social affairs, hunched over paperwork, as surprised to see us as we are to see her. She explains that we are in the right place: The village isn’t officially called Kurmanjan Datka, but that’s what the locals have started calling it since it let go of its Soviet name, Frunze Collective Farm.

Esenova’s husband is descended from Kurmanjan Datka, and she makes sure her own children know their lineage. She adds that every May Kurmanjan Datka’s descendants gather to celebrate her life with prayers, readings from the Qur’an and the breaking of seven loaves of bread, a local tradition.

“Kurmanjan Datka’s spirit has always helped the village,” she says. “The collective farm was run mostly by women, and it was always highly praised by the Soviets and won three big awards. Now the women are very active in local government.”

Esenova herself transitioned from being one of the leaders of the collective farm to local government. When asked about the film, she observes that “the one thing we didn’t like is that she was shown more as a warrior than as a woman. Our forefathers told us that she was very feminine, famous for her care and tenderness, for her cheerful personality. In the film, she didn’t talk much and behaved more like a man.”

One among the datka’s 1,500 descendants, Bazargul Koionbaeva directs the Kurmanjan Datka Museum of History and Ethnography in Gulcha, where images of Kurmanjan appear on the walls and cases display artifacts associated with her legacy. “Since the film came out, we have gotten more visitors, even from other countries,” she says.

According to international trade reviews of the film written when it debuted with subtitles at the Montreal World Film Festival in August 2014 and later in other venues abroad, it may not be so much whether the datka is too masculine or feminine, but rather that she is a bit flat. This isn’t a character-driven movie. The director is keener to talk about his intent to show as many elements of Kyrgyz culture as possible.

In this he has been successful. The cinematographer, Murat Aliyev, trained in Moscow and has been shooting films since 1966. “It was important to show the beauty of the country,” he says, chatting back in Bishkek at Sher-Niyaz’s production office, Aitysh Film. (The name refers to the art of improvised oral poetry.)

This also included filming a tiger, borrowed from the Moscow Zoo, amid nature, so it could appear each time Kurmanjan Datka has to summon strength.

“The tiger symbolizes freedom and courage. It’s good to show this woman as a tiger,” says Chorotegin. “In Kyrgyz culture, they might dream of tigers or lions. The Kyrgyz people—some of the tribes—think they are descendants of tigers. We are a nation of 40 tribes, and each tribe belongs to an animal, like one is the deer, the wolf, the bear.”

Kyrgyzstan is about the size of England, Wales and Scotland combined, but with a population of only 5.8 million, the whole country can feel like a small town. That’s how, on another day, we’re not surprised when we stop at a restaurant for lunch and the rambunctious group of young men and women at the next table includes an assistant cameraman on the film. Conversation follows.

“This film shows that our ancestors were strong,” says one of the women. “It shows our true values, like faith, dignity, honesty. Not the things young people are interested in nowadays unfortunately.”

But when asked to name their favorite Kyrgyz films, they tick off others: The White Ship, Red Apple and other films made in the 1970s and 1980s, an era of cinema now called “The Kyrgyz Miracle.”

Unlike the other Central Asian republics, the Soviets invested considerably in Kyrgyzstan’s film industry. It was the Soviets who in 1936 built Aitysh Film, and now Sher-Niyaz also rents it out to other filmmakers.

“We’re a complete studio, except that we cannot do Dolby Sound,” he says. “World figures in cinema like the late Michelangelo Antonioni once walked here. And of course, Aitmatov. It’s a sacred place for me.”

Located in Kurmanjan’s home area of Gulcha, near Osh, the second-largest city in Kyrgyzstan, the Kurmanjan Datka Museum of History and Ethnography is shaped like a traditional nomadic yurt.

He refers to Chingiz Aitmatov (1928-2008). This is also a country where the most famous person in its modern, post-Kurmanjan Datka history is a novelist. Aitmatov is commemorated in images everywhere, and he comes up in conversations routinely.

“Aitmatov is the reason the Soviets invested in film here,” says Kiyas Moldokasymov, the country’s oldest film historian. The author’s works were international successes, and they garnered attention on a global scale through film adaptations that won prizes around the world. “That’s why it was called The Kyrgyz Miracle,” Moldokasymov explains. “The Soviets gave a lot of money, and so many Kyrgyz trained in Moscow.”

Today that legacy of talent is also much employed in the country’s more prosperous neighbor and frequent rival Kazakhstan. Aliyev estimates half of Kazakhstan’s films are shot by Kyrgyz cameramen.

Moldokasymov reckons that about 10 to 15 local films a year are released annually, all with privately funded budgets “around $30,000.” Most are aimed at young people because, the film critic reasons, “people want to see themselves. So these are comedies, love stories and rural life stories in which youngsters can laugh at themselves.”

“If the government could fund one film every two years, that would be good,” Moldokasymov says. “We don’t have much money.”

Kurmanjan Datka’s $1.5 million budget was about a tenth of the cost of Kazakhstan’s most famous national film, the 2005 Nomad. “No one makes money on quality films here,” says Sher-Niyaz. “The actors were given $20 a day…. We can live on $200 a month here, so you could live on this salary if there was always work.

In Kyrgyzstan, theaters such as the Ala-Too in Bishkek, the capital, serve not only for leisure entertainment but also as a modern continuation of a culture long defined by epic oral narratives.

“An epic film on our budget,” he marvels. “That is something.”

Kyrgyz use the word “epic” frequently, and not in the casual sense that young people do in English these days. Because the epic poem is the leading national historical art form—the most famous is the epic of Manas, more than 1,000 years old and comprised of more than half a million lines—the culture of poetic song opens Kurmanjan Datka and recurs often, and even the datka herself was also an agyn, or master poet-singer.

“Using epic songs and poems was an integral part of nation-building after the Soviet collapse,” says heritage and literature professor Kuchumkulova.

Kurmanjan Datka’s own epic of 97 years ends in an 11th-century cemetery in Osh. In 2010 her husband’s memorial was moved alongside hers. I learn this from Mahmud aka (elder brother Mahmud), who is among the second generation in his family to guard the cemetery. Although it is primarily an Uzbek graveyard, Mahmud aka, who is Uzbek, says Kurmanjan Datka asked to be buried near the biggest mosque in the area, which was here at the time. More than 20 ethnic groups live in the Osh district, situated in Central Asia’s Fergana Valley, where Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan meet. There have always been tensions and clashes between the Kyrgyz and Uzbeks, but Mahmud aka likes the film too, insisting that because the modern borders are not exact, Kurmanjan Datka’s story belongs, to everyone, including Kyrgyzstan’s neighbors.

At one of our last stops, we are in the town of Cholpan Ata. We find several schoolgirls gathered outside a dilapidated cinema. They’ve been sent by their teacher to watch last year’s Zar Zaman (Desperate Times), about the Youth Revolution of April 2010, when people took to the streets of Bishkek to protest government corruption. They’ve seen Kurmanjan Datka—of course—and now they’re looking forward to studying her. The seats in the theater are falling apart, and the screen dates to the 1960s, but for their generation, this is where legends and history make and remake each other.

You may also be interested in...

Spotlight on Photography: Drinking in Türkiye’s Coffee Culture

Arts

‘Home’: Arab American National Museum Celebrates 20th Anniversary

Arts

Arab American National Museum Director Diana Abouali says the facility—which is marking its 20th anniversary in 2025—in Dearborn, Michigan, has aimed to create a home for Arab Americans by preserving and presenting the history, culture and contributions of Arab immigrants as well as their native-born children and grandchildren.

Art Biennial Reviving the Ancient City of Bukhara, Uzbekistan

History

Culture

Uzbekistan’s inaugural biennial reactivates an ancient stop on the Silk Road through artworks jointly created by international and Uzbek artists.