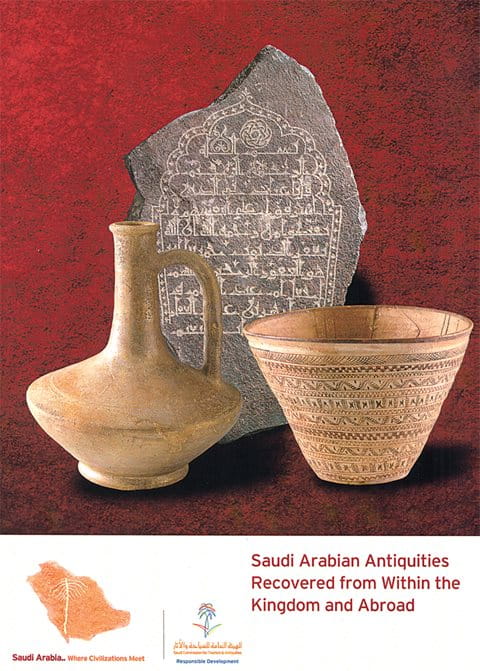

Returning Treasures to the Kingdom

Time was that a picnic in any of Saudi Arabia’s deserts might turn up an ancient pot or other artifact. Since 2012 more than 100 people have given back thousands of informally gathered artifacts in a uniquely successful, goodwill-based antiquities preservation campaign.

When Bob Ackerman set out with his family on a desert picnic one day in 1972 to Jubail near Saudi Arabia’s east coast, the farthest thing from his mind was archeology. A refinery engineer for the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco), Ackerman simply enjoyed the outdoors.

“For some reason I don’t understand and never will, some impulse caused me to bend over and scratch the sandy surface of this windblown area with my finger,” he says. He struck something hard. When he brushed away the sand, he found nine intact ceramic pots, each about a handspan wide at its mouth. He took three of them back to his home. After some research, he estimated they could be as much as 4,000 years old. When he returned to the us a few years later, he took the pots with him.

That was before Saudi Arabia had well-established museums and antiquities-preservation institutions, before regulations controlled the export of antiquities. For Ackerman and many others, including many Saudi citizens, such pots were just souvenirs of a not-too-extraordinary day’s outing.

Others, however, took their amateur collecting more seriously. This led to the popularity of the term “pot-picking” that, beginning in the 1950s, described a largely recreational activity that lasted through the late ’70s, when Saudi Arabia began its concerted effort to preserve its national archeological heritage at home.

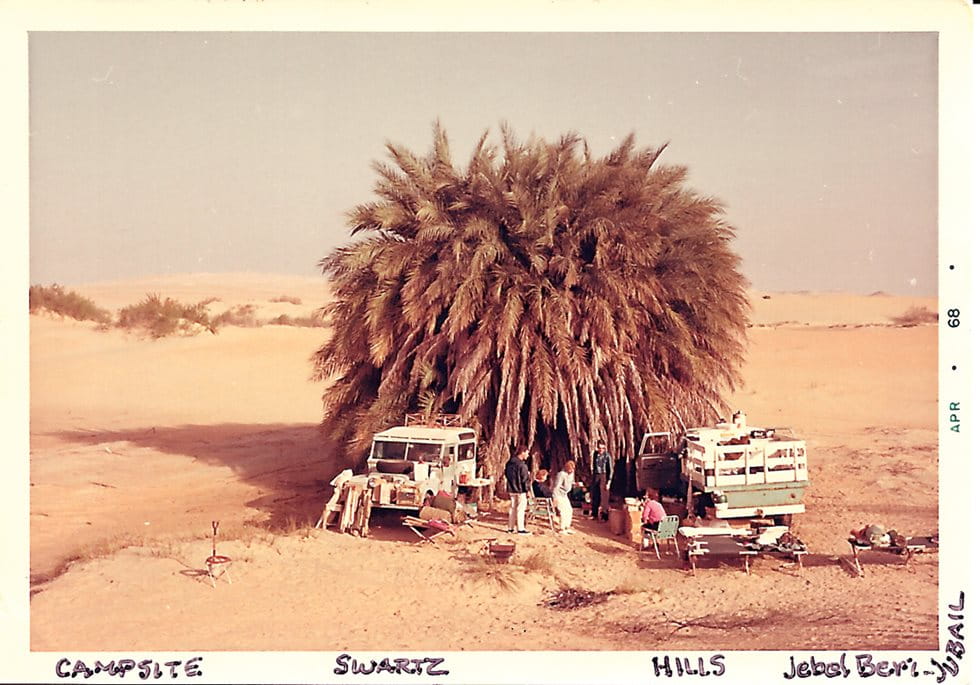

Beverly Swartz recalled this informal archeology as “an unequaled, heart-thumping thrill, no matter how many times we experienced it.” She and her husband, Carter, moved with their three children in 1958 to Dhahran, Aramco’s headquarters, where Carter helped guide management-training programs. On weekends and holidays, the family would join others to travel, explore, camp—and collect antiquities.

To date, some 46,000 items have been donated by more than 100 people. The artifacts will be housed at the National Museum in Riyadh as well as regional museums.

Swartz said that often their campsites were “littered with arrowheads and other Stone Age tools.” With her avid interest in archeology, she knew the significance of her family’s finds: The only problem was that there was no place to put them except in boxes and on shelves at home, organized by type and location.

Today, that’s no longer the case. Shortly after Saudi Arabia opened its National Museum in 2001 in Riyadh, it began formally to welcome antiquities home. In 2003 the country made preservation a goal of what is now the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage (sctnh), headed by Prince Sultan ibn Salman ibn Abdulaziz. Since then, the sctnh has focused much on the return of archeological artifacts from the private collections of Saudis and former expatriates to make them available for study and museum display.

It is an effort that relies almost entirely on goodwill. Ali I. Al-Ghabban, vice president of the sctnh, points out that almost every one of what now totals more than 46,000 objects—some 16,000 from Saudis and 30,000 from expatriates—has been handed over voluntarily. For Swartz and others, the process was satisfying. “When we started our desert excursions and artifact collecting, the kingdom was not yet focused on discovering and preserving archeological sites,” she said in an interview before her death in 2013. “We not only enjoyed our finds, but felt we were saving them for eventual recognition and identification. Their rightful home is back in Saudi Arabia.”

Left to right: This camel petroglyph was found in the 1970s on a rubble pile under a cliff in Wadi al-Faw that donor Pat Oertley describes as “mostly animals and stick figures.” Varieties of worked stone found over the course of several decades of off-road family camping trips, donated by Beverly Swartz. Glass bracelet fragments, some likely dating to Roman times, donated by Virginia Onnen.

In 1976 Saudi Arabia became signatory to the 1970 unesco Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, the first international legal framework for controlling traffic in cultural property. In the four decades since, repatriation of antiquities has become a global effort. Such repatriations “strengthen national sentiment [and] increase social cohesion,” says unesco spokesman Edouard Planche. “[They] also allow experts and tourists to study and to visit antiquities on the sites of origin,” while contributing to economic development through the tourism industry.

For example, the J. Paul Getty Museum in California has returned treasures to the Italian Ministry of Culture, while an exhibition in January at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo showed off about 200 antiquities from among some 500 that had been repatriated from the us, uk, Germany, Belgium and Australia.

“While the past belongs to all of us collectively, context is really key,” says Rachel Dewan, executive director of Saving Antiquities for All, a us-based nonprofit organization dedicated to thwarting smuggling and supporting antiquities repatriations. “The added meaning and significance of an object in its place of origin is powerful. Fortunately, many people around the world recognize this importance.”

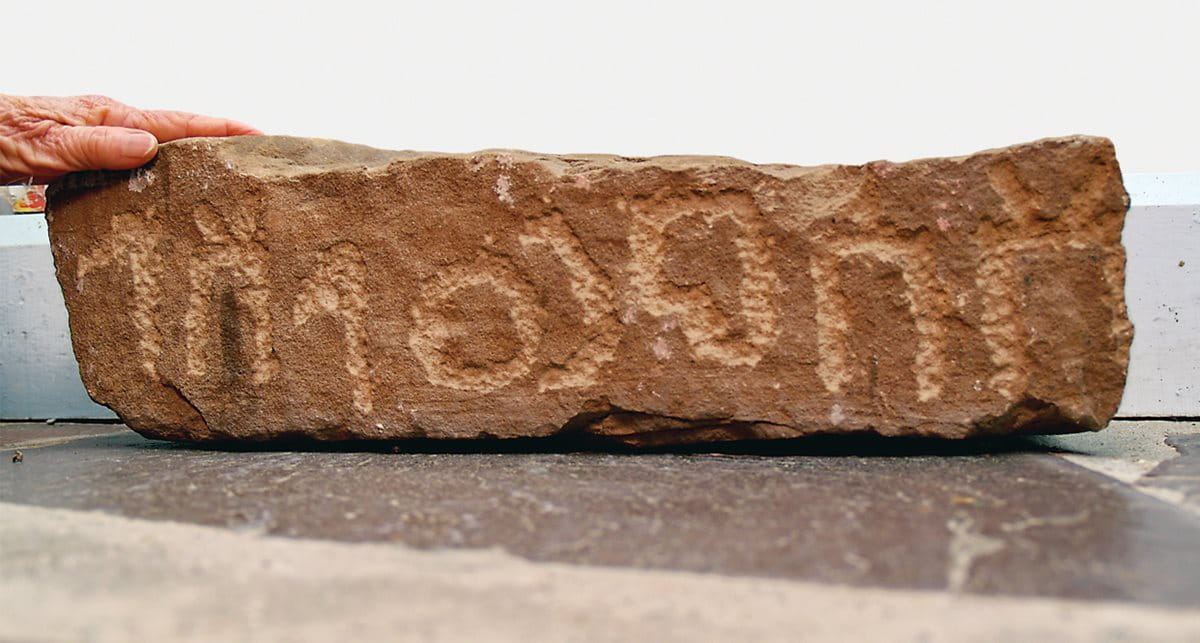

One of them was Elinor Nichols of Bailey’s Island, Massachusetts. Indeed, her wish to repatriate what she lightly calls “a rather heavy shipment of rocks”—140 kilograms in all, it turned out—helped set in motion the ongoing artifact-repatriation campaign aimed at former expatriates. Prominent in her collection were limestone and basalt grinding stones and a meter-long stone block inscribed with Taymanitic script dating to the sixth century bce. By 2012 what became the Antiquities Homecoming Project had harvested some 14,000 items from 14 us donors, and more came from an additional 25 donors later. The objects range from arrowheads to stone blades and axe-heads, and from glass bracelet pieces to petroglyphs, coins, clay pots, shards and figurines.

In response to Nichols’s donation, Prince Sultan wrote to her personally. “As you know, preserving and exhibiting ancient treasures of the kingdom has become a major cultural effort” with several goals, he explained. “First, to increase tourism to these unique sightseeing attractions, and second, to enhance the education of Saudi Arabians about their heritage and history. Our efforts to discover and preserve the treasures of our history has hit a responsive note among Saudis, who are eager to learn more of their past.”

A personal album photo shows the Swartz and Hills families, camped in the available shade near Jabal Berri (“Mt. Berri”) in the Jubail region in the northeast of Saudi Arabia. “When we started our desert excursions and artifact collecting, the kingdom was not yet focused on discovering and preserving archeological sites,” said Swartz. “We felt we were saving them for eventual recognition.”

Indeed, Saudis have responded positively. In 2012, Al-Ghabban accepted return of a heritage piece dating to the early period of Islam from Daifallah Al-Ghofaili, a private museum owner from al-Rass, northwest of the kingdom’s capital. “I was prompted to hand over the antique in recognition of the top priority and concern given by [sctnh] authorities to preserve these treasures,” Al-Ghofaili told the newspaper Al-Eqtisadiah. “This move would contribute substantially to highlighting the kingdom’s heritage and its sublime position in the human civilization,” he added.

Among Elinor Nichols’s donations was this pair of limestone grinding stones. The indentation near her finger held a wooden handle used to turn the top stone against the lower one. “We enjoyed looking at them around our home,” says Nichols. “As time passed, I realized they should all be returned.”

Similarly, the newspaper reported that Abdul Aziz bin Khaled Al-Sudairy donated 15 artifacts, including an inscribed marble-and-bronze piece from al-Ukhdud in the kingdom’s southwest that dates from between 600 and 300 bce. “No one except me, my children and those visiting us ever saw them,” he said, adding that he hoped his donation would enable more people to view them in museums.

In February 2012 Prince Sultan invited expatriate donors—many in their 70s and 80s, and most with Aramco connections—together with family members to join 80 Saudi donors in a ceremony of recognition held at the National Museum.

Addressing the expatriate donors, Prince Sultan said, “I’m very happy to see people and their children bringing back important treasures. We are experiencing the golden age of antiquities and heritage in Saudi Arabia.” The country is, he added, undertaking a national project to establish new, regionally focused museums. “You are not just giving back artifacts,” he said. “You are being part of a major heritage initiative.”

Found in 1969 by Roger and Elinor Nichols near Tayma, a caravan oasis town in northwest Saudi Arabia, this stone with a Taymanitic inscription was likely carved around the sixth century bce.

Princess Adela bint Abdullah, a daughter of late King Abdullah ibn Abdulaziz and head of the National Museum’s consultation committee, met with the expatriate women and complimented them. Many of the returned objects “were acquired by people who appreciated, valued and preserved them,” she said. Voluntarily repatriating precious artifacts “shows a great appreciation for the history of our nation. I believe the gesture was a great one as after keeping them for a long time some would feel that those pieces were part of their lives.”

This struck a chord with donor Pat Oertley, who had donated a camel petroglyph that she had found on a pile of rubble under a cliff that was inscribed with “mostly animals and a few stick figures” at Wadi al-Faw in southwestern Saudi Arabia. “I’m very pleased to return the camel, but I will miss him,” she said.

Of the three pots Ackerman found while picnicking, he said simply, “They belong in Saudi Arabia. I’m pleased to have the opportunity to return them.”

You may also be interested in...

Nakshi Kantha Embroidery: Tales of Heritage and Revival

Arts

History

A traditional form of quilting in Bangladesh in which women embroider family history, love and memory into the fabric is blanketing markets locally and beyond.

AramcoWorld: Celebrating 75 Years of Global Historical Insight

History

Cover stories that bridge the past and present offer insights into humanity’s common ground. From archeology to historical objects, people, places and more we share connections to one another.

How a Portuguese Town Rediscovered Its Islamic Roots

History

Arts

Thanks to children who kicked up little pieces of red ceramics while playing on a hilltop in 1977, the town of Mértola, Portugal, has taken its place alongside much of the rest of the country as it rediscovers its Islamic past. Years of excavations have turned Mértola, which lies near the border with Spain, into a destination for both tourists and researchers, and officials have applied to make Mértola a UNESCO World Heritage Site.