The Unlikely Sisterhood of Seattle and Tashkent

In 1973, the us port renowned for rain and the Soviet-run capital in semi-arid Central Asia could hardly have appeared more different, but what began then as the first us-Soviet sister city pairing has blossomed into 43 years of mutual enrichment and heartfelt friendship—at first despite the Cold War, and later boosted by Seattle’s economic growth and Uzbekistan’s independence.

The bright red sign for the Seattle Café is hard to miss on Bratislava Ko’chasi,

a busy, leafy boulevard that runs through the center of Tashkent, capital of the Central Asian country of Uzbekistan. Bold letters spell out the name in Uzbek, English and Russian, hinting that this popular restaurant serves more than just tasty Uzbek cuisine. It also offers a glimpse into a 43-year-old friendship between two cities whose differences are as great as the 10,100 kilometers and 13 time zones that separate them.

The shaded patio in front of the café overlooks the Seattle-Tashkent Peace Park, built in 1988 and now known as Babur Park. Although only about a city block in size, the park is a symbolic heart of the two cities’ relationship. Central Asian pines grow alongside apricot, mulberry and wild plum trees fed by water trickling through narrow irrigation canals lined with square ceramic tiles, each hand-decorated 27 years ago mostly by schoolchildren in Seattle. Ten thousand of them trace the canals, ring tree encasements and decorate the park’s fountain. Many of the tiles are now cracked and their colors are fading, but their heartfelt messages of peace, cooperation and friendship remain vibrant.

“It’s really important for our two countries to have a park like this,” comments café owner Javon Nazarov, who has safeguarded photos and the history of the park since its inception. “When the American volunteers came to help build the park, we realized that they believe the same thing we do—that peace is the most important thing in life.”

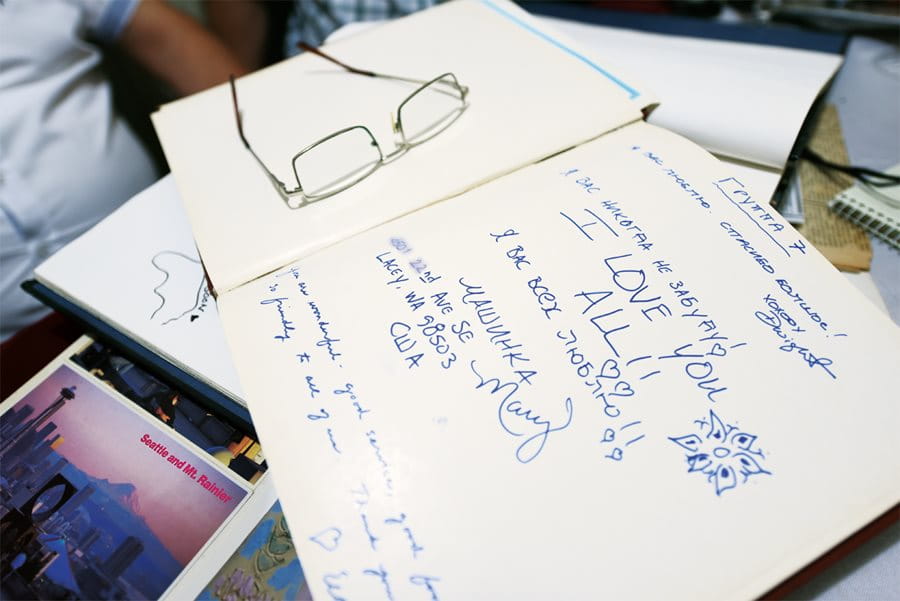

Situated across from the Seattle-Tashkent Peace Park, the café and its owner, Javon Nazarov, right, preserve both heart and history from more than 43 years of visitors, volunteers and delegations in scrapbooks, above.

How Seattle, Washington, established a sister city relationship with then-Soviet Tashkent during the Cold War is a story that begins in 1971, 17 years before the park was built. It is a story of serendipity, courage, extraordinary citizen diplomacy and a bit of political intrigue.

In August 1971, Alaska Airlines invited mayors from three of the larger Soviet cities—Tashkent, Irkutsk and Sochi—to visit its headquarters in Seattle as part of its quest to open new routes into the Soviet Union. “They asked me if I would come and join the mayors for dinner at the top of the Space Needle,” recalls Wes Uhlman, who was then mayor of Seattle. “I sat next to Mayor Husnitdin Asamov of Tashkent, who didn’t speak any English, but I spoke a little Russian, and we talked about continuing our relationship,” he says.

When President Richard Nixon announced in March 1972 that he would take his first official trip to Moscow in May, Uhlman sent Asamov a letter formally suggesting Seattle and Tashkent establish the first us-Soviet sister city relationship. Although Nixon’s visit represented a culmination of détente, the thaw in Cold War us-Soviet relations that had begun in 1969, “tensions were still very high between our two countries,” notes Uhlman.

He remembers also the incredulity of Seattle City Council members when he approached them with the idea. “They asked me, where in the world is Uzbekistan, and why should we get involved?” Uhlman recalls explaining how important it was to tone down angry rhetoric between the superpowers, and says the council was persuaded that a sister city relationship might contribute toward that. It wasn’t a hard sell, recalls Uhlman. “Our city has always been progressive.” In October 1972, Tashkent’s new mayor, Vahid Kazimov, agreed to Uhlman’s suggestion. “It will be a great honor for us to establish permanent friendly and business contacts with the city of Seattle,” wrote Kazimov.

Uhlman soon discovered that city council skepticism was not the only official obstacle. “Our State Department discouraged these kinds of relationships because of all the tensions occurring on a macro level,” says Uhlman, whose request to form the sister city was quickly denied. He turned to a good friend, Washington Senator Warren Magnuson, who was serving as Chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee that oversaw the State Department’s budget. Magnuson was well known for his progressive politics, and according to Uhlman, the Senator called Secretary of State William Rogers into his office, and “within a week we received our letter of approval,” he recalls, laughing.

Creating the first us-Soviet sister city bond was courageous, asserts Seattleite Gary Furlong, currently the us Honorary Consul General of Uzbekistan to the Western United States and a former president of the Seattle-Tashkent Sister City Association (stsca). “I think it was inspiring, and for Seattle, it was really an opening to the world in a unique way. It was a positive and very high profile example,” he emphasizes.

With Cold War tensions high in the early 1970s, “it took a lot of courage then for someone in a city in the United States, even in a progressive city like Seattle, to form a partnership with a Soviet city,” says Dan Peterson, who served as president of the Seattle-Tashkent Sister City Association (stsca) from 2006 to 2016. The relationship was “a good way to bring two countries closer, the better to work for peace.”

Dan Peterson, president of the stsca since 2006, agrees. “It took a lot of courage then for someone in a city in the United States, even in a progressive city like Seattle, to form a partnership with a Soviet city,” says Peterson. “Some of us grew up during the Cold War era, and we were told this is not a good thing. And what did we discover? That they are people just like the rest of us.”

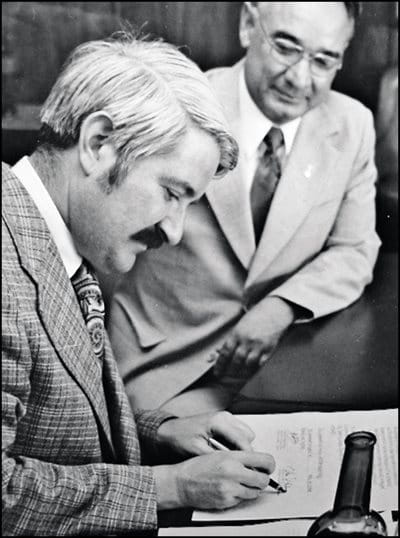

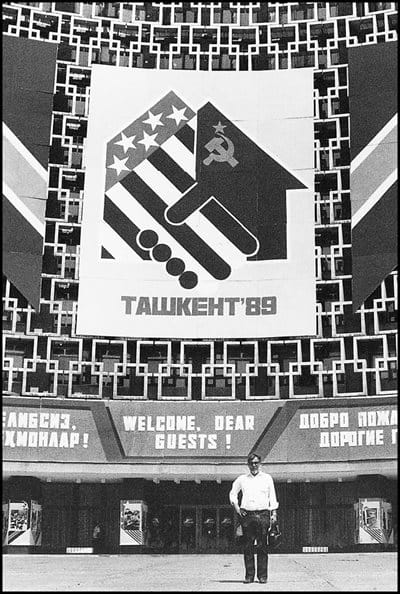

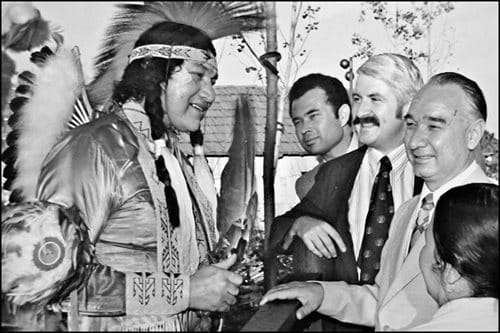

Above: At a ceremony in Seattle in 1973, Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman put his signature on a sister city memorandum after Tashkent Mayor Vahid Kazimov, who looks on. Below: In 1989, the Hotel Uzbekistan in Tashkent welcomed a Seattle delegation in three languages: Uzbek, English and Russian.

To Peterson, it was not surprising Seattle became the first us city to do this. “Seattle citizens pride themselves on being forward-looking, peace-loving and well educated about world issues,” he notes. One of the most troubling and motivating issues at the time, and later into the 1980s, was the threat of nuclear warfare between the superpowers, and to Seattleites, a partnership with Tashkent was a good way to bring two countries closer, the better to work for peace.

At the same time Uhlman was drafting his March letter to Mayor Asamov, Ilse Cirtautas, Ph.D., a prominent Turkologist in the Department of Near East Languages and Civilization at the University of Washington in Seattle, was arriving in Tashkent for a previously arranged research trip. Renowned for her expertise in the Uzbek language and culture, Cirtautas came to work with colleagues at the Uzbek Academy of Science as well as at the Institute of Uzbek Language and Literature. (See sidebar, below)

Her colleagues in Tashkent, however, had something else in mind, too. They invited her to a meeting of the O’zbekistan Do’stlik Jamiyati (Uzbek Friendship Society) where “they asked me to help them establish a sister city—or ‘brother city’ relationship as it is called in Uzbek—between Tashkent and the place I come from,” recalls Cirtautas. “They didn’t even know where I came from at that point!”

She replied with concern about the distance between the two cities as well as the vast cultural differences. When none of that seemed to matter, it became clear that her colleagues might be looking to plant seeds for an independent future. “They clearly wanted to have a place in the West where they could send their educated people whom they trusted with a view toward independence. They weren’t happy under the colonial rule of the Russians,” asserts Cirtautas.

Neither Cirtautas nor her colleagues in Tashkent were aware that Mayors Uhlman and Kazimov were already discussing sister city relations. After learning in October that Tashkent had agreed, Cirtautas met with Uhlman to brief him about Uzbekistan. “I assured him that the native population is Uzbek, not Russian, and that they are wonderful, smiling people!” Perplexed by how quickly Moscow also approved the relationship, Cirtautas later discovered the simple answer when Kazimov told her the Soviets wanted commercial access to Seattle-based Boeing Company.

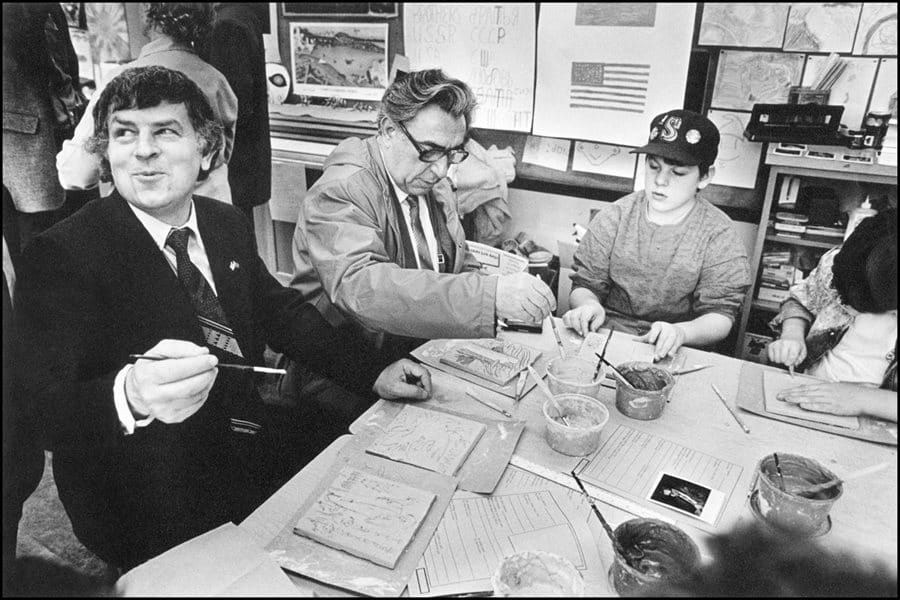

In April 1983, Mayor Kazimov and Tashkent officials hosted a delegation from Target Seattle, one of a number of people-to-people diplomacy efforts supported by the stsca.

On January 23, 1973, the Seattle City Council passed its resolution adopting Tashkent as a sister city. In June of that year, Seattle Deputy Mayor John Chambers and Hugh Smith, a prominent businessman active in the Seattle Chamber of Commerce and chairman of the new stsca, signed the formal joint communiqué with Mayor Kazimov in Tashkent. With the strokes of two pens, two cities were united whose histories, cultures, religions, geographies and even climates could not have been more different. What both cities did have in common was a faith in the value of people-to-people diplomacy and a mutual longing for peaceful coexistence.

During the early years of the relationship, it was all about getting to know each other. Uhlman took the first Seattle delegation to Tashkent in April 1974; in June Kazimov reciprocated with a delegation of government officials and academics, and they participated in the dedication of Tashkent Park near downtown Seattle. Later that year, Cirtautas established relations between Tashkent State University and the University of Washington, one of many academic connections she would facilitate over the years.

Uhlman recalls that during those first visits, Soviet Uzbekistan was a closed society. “There was very little personal exposure to the rest of the world in Tashkent at that time,” he comments, adding that he believes that the new relationship helped Uzbeks do exactly what they intended it to do: open up a reevaluation of their relationship to the world.

The spirit of friendship reached a peak in the summer of 1988, when more than 200 volunteers from Washington state and the Tashkent region joined to build the Seattle-Tashkent Peace Park, dedicated on September 12 that year. The centerpiece was a fountain and pool ringed by tiles, above and right, each one individually hand-painted in Seattle and carried to Tashkent. Many were made by students, such as those at the Orca-Day Elementary School, lower, who were joined in their effort by visiting Tashkent sculptor Yakov Shapiro and Tashkent city architect Leon Adamov.

During the détente years of the ’70s, Furlong notes that “it was all about increasing understanding on our side, and for Tashkent, we were their main point of contact with the Western world…. Moscow opened the door to the West a tiny crack and the Uzbeks were brilliant at continuing to pry that crack open. The Uzbek side wanted to keep this going and worked very hard to make sure this continued,” he says, referring to Uzbek support for reciprocal delegations in the mid-1970s as well as their ability to maintain contact between the two cities even in the midst of recurrent political tensions.

The stsca faced challenges during those years, too. Local Baltic and Slavic communities objected that contact with Tashkent endorsed Russification and suppression of non-Russian populations. When mounting global tensions in the mid-to-late ’70s made cross-cultural exchanges difficult, Seattleites countered by increasing local educational programs about Central Asia. Following the 1978 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, they resisted pressure from the federal government to follow in the footsteps of other us sister cities to sever all ties with Soviet counterparts, citing the sister city founding principles laid down in 1956 by us President Dwight D. Eisenhower. (See sidebar, above, right.) Mayor Charles Royer supported them. “The mayor said, ‘We are not going to do that. We think this relationship matters,’” recalls Furlong, underlining the magnitude of this challenge. “We did not end that relationship. We’ve been there, we stuck with them, and they remember that.”

In 1985, Tashkent Mayor Shukurulla Mirsayidov tested Glasnost reforms of then-new Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev by sending Seattle the largest Soviet sister city delegation to ever visit the us.

In 1974, a joint delegation led by Ulhman and Kazimov, above, visited Spokane Expo ‘74, where contact with native North American peoples, traditions and history proved especially meaningful among Uzbek visitors. Although tiles made in 1988, left, showed Soviet and us flags, the flag of Uzbekistan, independent since 1991, appears, above right, with the us flag outside Seattle’s annual stsca-sponsored Navr’oz celebration, where, below, a traditional dancer performs.

“When Glasnost happened and Mayor Mirsayidov came to Seattle, we realized that this was the moment so many of us had been waiting decades for. It was time to dig in, full speed ahead,” exclaims Rosanne Royer, who co-chaired the stsca from 1978 to 1990. “We were the favorites then to connect with as far as sister cities go, and our exchanges started flying like crazy. Given the time differences between Seattle and Tashkent, we were up day and night, and people were calling us right and left,” recalls Royer, who was married to the mayor at that time. “It totally ate up all our time but delivered great rewards because we had fabulous people running every one of those exchanges.”

“What was fascinating about the Seattle-Tashkent Sister City Association is that the pre-independence years were amazing in terms of the breadth of exchanges,” comments Fred Lundahl, a current board member and retired diplomat whose last assignment was at the us embassy in Tashkent from 1997 to 2001.

“This was a time of incredibly fun and robust relationships because both cities wanted to showcase their best sides. It showed the Seattle community that there were people just like us in Uzbekistan.” Speaking with friends back in Tashkent who were involved in sister city programs during the early years, Lundahl notes that they expressed the same sentiment. “The human element,” he emphasizes, “has always been the key to this sister city relationship.”

Leading Uzbek literary figures like Muhammad Ali Akhmedov, chairman of the Writers’ Union of Uzbekistan, began visiting Seattle’s University of Washington in the late 1980s, awakening interest in the Uzbek language and cementing ties with faculty and students.

Mirsayidov’s 1985 visit and the hopeful tone of Glasnost unleashed conferences, cultural programs, exchanges and delegations, all in the years leading up to Uzbekistan’s independence in September 1991. It was a time of extraordinary “person-to-person citizen diplomacy” and cross-cultural education.

“There are literally thousands of people in Seattle who participated in these exchanges over the years in one way or another,” says Paul Natkin, a Seattle-based artist and certified Russian-language interpreter. Four decades later, Paul and many Seattle participants remember their experiences as if it were yesterday.

Natkin worked on several artist exchanges and exhibits. “Orchestrating these exchanges can be very hard,” he notes, “when you have systems and histories and structures that are so different. But learning to work with that is part of what makes the experience so important and valuable.” His involvement with the sister city, he adds, led to a lasting friendship with renowned Tashkent artist Marat Sadykov and his family.

Jay Sasnett, now a retired middle school geography teacher, participated in three middle and high school student and teacher trips to Tashkent from 1985 to 1988, and he oversaw additional sister city education exchanges with help from his wife, Susan, also a teacher. “It is one of the things I am most proud of,” emphasizes Sasnett. “These trips and the work we did to prepare for them transformed the lives of several hundred middle and high school youths and teachers in Seattle.”

Sasnett vividly recalls his excitement during the first trip, and he remembers how each of the four Tashkent schools they visited with 10 students, all in sixth to eighth grade, rolled out the welcome mat. “It was such an inspiring trip,” he notes. Growing interest attracted more students, teachers and schools to the subsequent stsca trips. “It was a time when the Cold War had reached its peak, and Seattle was a hotbed of citizen diplomacy,” notes Sasnett. “We wanted to let the Soviets know who we were.”

The last 1988 exchange involved 86 students and teachers from 10 different Seattle schools. On that trip, students lived with Uzbek families and went to school with their new friends for a week of complete immersion into a new and very different Muslim culture. The effects were overwhelming. “On the way home, the kids were crying, some of them even sobbing on the plane,” recalls Sasnett. “These kids’ lives were clearly changed, that’s how powerful an experience it was for them.” There were tears too from adults when it was time to leave Tashkent, adds Natkin, who participated in this trip.

“We had trouble processing why this was happening to us,” he recalls. “We thought about how far away we lived, and how we were all trying to connect with each other, and the possibility we would never see each other again. It was hard to fathom.”

“It was a heady time then in Seattle,” recalls Frith Maier. “There were so many different exchanges that happened through the sister city initiative.” Now a 53-year-old serial entrepreneur, Maier was a recent college graduate when she proposed a mountaineering exchange to the stsca in 1987. Fluent in Russian and passionate about climbing, Maier was delighted when her proposal was accepted. She assembled a group of Washington climbers, and in August 1987 they flew to Tashkent, met their counterparts and tackled mountains in a part of the Pamir range where no foreigners had ever climbed before.

“What made the Seattle-Tashkent mountaineering exchange extraordinary is that we were able to go out into the mountains, sit around a campfire and talk freely,” Maier explains. “We were dealing with physical challenges and climbing high ascents in mountains where you need to rely on each other. That brings communication to a level where you drop all preconceived notions and have meaningful discussions.”

Maier’s second and final exchange in 1988 brought Tashkent alpinists to Seattle, where their climbs took them through small towns in the Cascade Mountains east of Seattle. She recalls how moving it was when the Russian and Uzbek climbers experienced a Fourth of July picnic in the small town of Leavenworth. “They thought it was so much fun, and in these small towns there was less exposure to the perception of the Soviet Union as our enemy. In their eyes, the climbers were just real people. This is what excites me about citizen diplomacy,” Maier emphasizes. “It makes it easy to get beyond the labels and just connect with people on a human level.”

While the stsca was organizing exchanges, at the University of Washington, Cirtautas was cementing relationships among Uzbek academics, poets and writers in Tashkent and her university in Seattle. As the first appointed member of the stsca in 1973, Cirtautas was critical to bringing it the university’s backing. “Having institutional support really helps sustain an organization like ours, and the University of Washington as well as the Jackson School of International Studies have been strong supporters for a long time,” comments Peterson.

Above: Participants in the first teacher exchanges to Seattle between 2004 and 2006, Fatima Tashpulatova, Zukhra Miliyeva and Zukhra Salikhodjaeva came from Tashkent School 17, where a former administrator, below, right, holds a Seattle souvenir as a reminder of the relationships that grew among teachers in the sister cities. In addition to bringing home lesson plans from Seattle they still use, “we also shared our teaching methods,” explains Tashpulatova, “and we told them everything about our traditions, customs and habits.”

During the mid-to-late ’80s, Cirtautas facilitated student and faculty exchanges between the University of Washington and Tashkent State University (now the National University of Uzbekistan), and she organized symposia on Central Asian studies. In 1989, the creation of the Central Asian Languages and Culture Summer Programs gave her the opportunity to invite Uzbek poets and writers to Seattle.

The visits of poets Abdulla Oripov and Erkin Vohidov spurred student interest in the Uzbek language and culture, says Cirtautas. It also made students aware of the struggles within Soviet-occupied Uzbekistan on the eve of its independence. As members of the “Generation of the 1960s,” the poets appealed for the revival of their Uzbek language, history and culture through poems that focused on topics such as “My Country” and “My Language.”

Summer translation workshops also gave students the chance to work alongside Uzbekistan’s nationally revered writer Muhammad Ali Akhmedov from 1992 until 2005. “I was really surprised that students were interested in learning Uzbek,” comments Akhmedov, now chairman of the Writers’ Union of Uzbekistan. “During the Soviet times, even Russians who lived in Uzbekistan weren’t interested in learning Uzbek. They said they didn’t need it.” He recalls happily how interested the students were in his Uzbek culture. “I really liked the idea that I could do something for these students so they could learn about the richness of our language and our culture.”

Over the four decades, more than 100 projects and exchanges (see sidebar below) underscore how the sister city relationship stimulated both sides. Nothing, however, left as tangible a footprint in Tashkent as Babur Park. “The park is the most visible reminder of our city in the middle of Tashkent,” emphasizes Peterson. Royer agrees. “When it comes to something in terms of a tangible expression of Seattle really caring about our connection with Tashkent, there just isn’t anything that can even compare with the peace park. You decide to become a volunteer to build a park because you think it’s a great idea, and all of a sudden you realize you are learning about Central Asia, a part of the world you never knew about, and you are learning about the Uzbek people.”

The park project originated with Ploughshares, a Seattle-based organization founded by former Peace Corps volunteers who were looking for ways to defuse Cold War tensions. Aware of Seattle’s ties to Tashkent, Ploughshares shifted the location for a peace park from Moscow to Tashkent after they received wholehearted support from then-Mayor Mirsayidov. “As we say in the Orient,” commented Mirsayidov to a local publication at that time, “people who plant trees together will never be enemies. But we want more than that. We want to be friends forever.”

The sister city was one of Uzbekistan’s early initiatives to reach out beyond its Soviet orbit, and Tashkent’s lively street life today is in part one of the fruits of its many such efforts, which included more than 100 exchanges in dozens of fields both between 1974 and independence in 1991 and today, where the emphasis is more on technical and administrative exchanges. “Moscow opened the door to the West a tiny crack, and the Uzbeks were brilliant at continuing to pry that crack open,” notes us diplomat Gary Furlong.

Fred Noland, co-founder of Ploughshares, took a leave of absence from his law firm to oversee the project. Architects and landscapers donated their expertise, Seattle sculptor Richard Beyer gifted a six-meter-tall sculpture to the park, and the “10,000 Tiles for Tashkent” project involved thousands of schoolchildren and adults, as well as Seattle’s mayor and Washington state’s governor, who all painted tiles that would be laid in the park. “These projects gained so much visibility in Seattle that we were getting volunteers all the time,” recalls Noland. “It was a rare and wonderful example of how one project can catch people’s imagination.”

In the summer of 1988, 175 volunteers from Seattle and 10 other states toiled in blistering heat side by side with several hundred Tashkent workers to build the park. Margaret Hopstein, a Russian born in Tashkent, was already a professor and head of the Department of Western Languages at the Literature Institute when the mayor’s office asked her to be a translator for the Americans. “My life was dedicated to that project in the summer of 1988. It was fascinating to me that a group of people from another continent would come to work in the heat and do manual labor for the sake of a potential friendship!”

Hopstein befriended one of the volunteers, Seattle software engineer Bruce Haley, and he remembers how rewarding it was to be in Tashkent not as a tourist but as someone who was working on a project intended to strengthen ties between two countries. “It allowed me to have a much deeper connection with the people there,” emphasizes Haley, who remained friends with Hopstein after she and her family immigrated to the us in 1990.

“The Seattleites’ energy inspired many Tashkenters,” asserts Hopstein. “As a human effort, it changed scores and scores of lives in Tashkent for the better, and I also think it changed lives in Seattle.” She recalls how local workers brought their children to meet and play games with the Americans and how teachers would stop by, excited to have their first words in English with a native speaker. “These simple acts were so human and attracted many Tashkenters who came to the park and opened their hearts,” says Hopstein. She emphasizes that the warmth of the American volunteers made such an impression that some of the peace park interpreters “later immigrated to Seattle and now have children who are American citizens.”

Since Silk Road times, Tashkent has thrived as a commercial hub for both industries and crafts, including textiles, here still woven by hand in the historic Yodgorlik factory in Margilan City, southeast of Tashkent. Below: Roots of the sisterhood lay also in air travel: In the ‘70s, Alaska Airlines sought regular routes into the Soviet Union, and the Soviets, notes Cirtautas, wanted commercial access to Seattle-based Boeing Company—a desire that came to fruition mainly after independence, when Uzbek Airways acquired an all-Boeing fleet. The first 767, delivered in 2004, Cirtautas recalls, arrived loaded with books and other donations.

Nazarov was managing the Seattle Café when the first park volunteers arrived. He had helped renovate the building, once a historic granary dating back to the mid-1800s, which was then given its name in 1985 by Mayor Mirsayidov. “The volunteers did their jobs and I fed them. We became friends.” Sitting at a table in the café’s patio overlooking the park one afternoon, he slowly leafs through albums full of pictures, newspaper clippings, postcards and handwritten notes he has collected since that summer, smiling when he comes across faces he still clearly remembers.

“This park has played a big role in my life,” explains Nazarov, who bought the café in 1994. “Over the past 27 years, I have met many people from the Seattle city administration and from the sister city association, but no one knows the true history of the park, so they ask me. I am the only one who knows the story from day one.” Nazarov turns to a page in the album and points to the words written by Rosanne Royer when the park was dedicated in September 1988: “If we have become a better city in the last 15 years, it is in part because we have learned a great deal from our friends in Tashkent.”

Now renamed Bobur Bo’gi (Babur Park), the Seattle-Tashkent Peace Park occupies about two blocks of land, providing a shady oasis for art students, above. “The park is the most visible reminder of our city in the middle of Tashkent,” says Peterson. Right: The tiled “Earth Mound” connects irrigation channels that water the park’s fruit trees, lower left, protected by square pools decorated with the handmade tiles from Seattle. Below, right: Ilhom Miliyev is a long-standing member of the Seattle association in Tashkent and a 2002 Hubert Humphrey Fellow. “My involvement has really changed my life and made it more meaningful,” he explains. “I am helping to strengthen relations between Tashkent and Seattle and improve friendships between American and Uzbek citizens.” He drops by the park regularly to check on its upkeep.

When Uzbekistan became independent in December 1991, Tashkent turned to its trusted friends in Seattle for advice. Exchange programs continued, but the emphasis shifted toward practical concerns: business development, social services, health care, public administration internships and teacher exchanges. The long-hoped-for connection with Boeing bore fruit, too, when in 2004 the first Boeing 767-33 was delivered to Uzbekistan Airways—filled with scholarly books for a new University of Washington Research Center as well as donations of clothing and toys for Tashkent orphanages.

Three Uzbek teachers from School 17, Fatima Tashpulatova, Zukhra Miliyeva and Zukhra Salikhodjaeva, participated in the first Tashkent teacher exchanges to Seattle between 2004 and 2006. They brought home lesson plans from their Seattle colleagues that they still use in their English-language classrooms today. “We also shared our teaching methods with the teachers and students in the Seattle schools we visited, and we told them everything about our traditions, customs and habits,” explains Tashpulatova. Her colleagues agree with her when she notes that “we brought the best back from America to Tashkent, and we think the same will happen with American teachers when they come here and visit our schools.”

Business delegations from Tashkent in 2008 and 2013 met with Seattle’s Trade Development Alliance, as well as with city officials responsible for issues ranging from water and waste management to recycling. Tashkent Deputy Mayor Ikrombek Berdibekov and Firuza Khodjaeva, deputy head of protocol at the Hokimiyat (city hall), led the 2013 delegation and recall the impressions of their stay in Seattle, from city landscaping to architectural styles to the development of emerging businesses. “We looked at everything, met with businesses and city officials, and brought back the best ideas that we thought could be implemented in Tashkent,” explains Berdibekov.

A couple chats in the park framed by the sculpture donated in 1988 by Seattle artist Richard Beyer.

“We can see that the activity between our sister cities is really developing during the years after independence,” says Khodjaeva, who has been the stcsa’s counterpart in Tashkent since 1998. “I would say that there is a difference in relations before and after independence,” she adds, noting that some of the earlier delegations and exchanges seemed more formal under the watchful eyes of the Soviets.

Khodjaeva emphasizes that sister city relations have become more important than ever today for both Tashkent as a city and for the Uzbek national government. “We have many sister cities now, but Seattle is one of the best among them because we communicate more with each other.” Grateful for the warm reception her delegation received in 2013, Khodjaeva admits that she feels like Seattle has become her second hometown.

Tashkent resident Ilhom Miliyev shares her affection for Seattle. After meeting Peterson and other members of the Seattle association in Tashkent, he became the sister city’s staunchest citizen advocate, and its only continuous local volunteer for the past 11 years. “I was also really impressed by so much of what I saw in the us,” says Miliyev, who spent one year in America as the recipient of a coveted Hubert Humphrey Fellowship in 2002. “As an Uzbek citizen, I wanted to bring back what I learned to Tashkent and promote friendship ties between our two countries, especially now that we are an independent nation.”

Miliyev describes the sister city association as a unique way for him to get involved in a civic activity. “My involvement has really changed my life and made it more meaningful,” he explains. “I am helping to strengthen relations between Tashkent and Seattle and improve friendships between American and Uzbek citizens.”

From old to young and comprising some 300 people, the Uzbek community that has grown in Seattle since the ‘70s is, in part, another result of the sister city exchanges. Each spring the stsca helps sponsor a community celebration of Navr’oz, a leading holiday in Uzbekistan. Dilbar Akhmedova, one of Seattle’s sister city migrants, says it is important not only for introducing Seattleites to her country, but also for helping Uzbeks who are growing up in the us to learn about their own unique culture of origin.

During the week, he often stops by Babur Park to check on its upkeep and to see if any tiles need repair. Miliyev recalls that the fate of the park was in peril after 1991 when the newly independent Uzbek government began to purge the city of all sites, parks and monuments that were reminders of the Soviet era. Plans to rebuild the park were thankfully scrapped, and Miliyev believes the importance of the Seattle-Tashkent relationship played a role in that decision.

Miliyev’s sense of loyalty and civic responsibility encapsulates much about the hospitality-intensive Uzbek culture that has so deeply motivated Seattle volunteers to maintain and strengthen the bridge between their cities over 43 years. Even through challenging political times, “people were eager to be involved because they had developed a love of the region,” says Joanne Young, a former Seattle-Tashkent Sister City Association president. “There is a lot of affection, a lot of heart, and there is something very compelling about Uzbekistan and the people who live there.”

“What sustains these partnerships is the individual commitment of the people,” comments us Ambassador to Uzbekistan Pamela Spratlen. “I’ve been impressed as I’ve gotten to know the people from Seattle who have given tremendous amounts of their personal time and energy, and the same is true when it comes to Tashkent. Some people are doing this out of their heart. I think that’s a testament to what people can do working together because they just want to do it. This sister city is extremely important to me personally,” adds the ambassador, who also has family ties to Seattle. “I very much intend to continue the current programs and try to build new ones.”

In addition to the embassy’s support, Peterson credits the Seattle City Council, the Tashkent mayor’s office, Cirtautas and the University of Washington, and of course the countless volunteers for helping the stsca to remain active. As a result, “our work has led to footprints in Seattle,” notes Peterson. “We have a Tashkent Park, which is now being renovated and upgraded. Uzbekistan Airways is an all-Boeing fleet, and when their planes are produced in Seattle, they are a visible reminder for the workers about a far-off land. Lastly, sister city events such as Navr’oz [spring festival] and our annual picnic promote the Uzbek culture in Seattle”—as does Seattle’s growing Uzbek community itself.

Since the ‘70s, Seattle has kept Tashkent Park on a hill above downtown, where a few dozen of the “10,000 Tiles for Tashkent” were also used. This year it is being renovated—a reminder that the 43-year-old sisterhood is alive and well.

Many Tashkenters like Hopstein, Fazliddin Shamsiev and Dilbar Akhmedova came to Seattle as a result of the sister city relationship. At approximately 300 people, it may not be the largest Uzbek community in the us, according to Peterson, but it is tight-knit and active. Akhmedova says it is important not only for introducing Seattleites to her country, but also for helping Uzbeks who are growing up in the us to learn about their unique culture of origin. “We want to help the young Uzbeks feel successful and integrate into our society,” says Peterson. “They are the future for maintaining the sister city relationship.”

Today, neither city looks much like it did in 1973. Seattle boomed on computers while Tashkent thrived on independence; metropolitan populations now run 3.6 and 2.6 million, respectively. Tashkent Deputy Mayor Berdibekov points proudly to his country’s now-diversified industrial and agrarian infrastructure, to its independence and also to the success of his city’s 43-year friendship with Seattle. “Even in Soviet times in 1973, it was a great event to establish this relationship, and it has been wonderful for our city,” notes the deputy mayor. He adds that future plans with Seattle include sending a delegation of women entrepreneurs from Tashkent to Seattle, internships for Uzbek English teachers and organizing a trade exhibit of Uzbek products.

Uzbekistan’s multi-ethnic culture is reflected in the faces on every street corner in Tashkent, a reminder of the many cultures that passed through the city when it was an important stop along the Silk Road. More than 100 ethnic groups co-exist in Uzbekistan, including Tajiks, Kazaks, Karakalpaks, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, Tatars, Turkmens, Ukranians and Koreans, to name only a few, making Uzbekistan almost as much of a melting pot as America.

Sharing 43 years of memories on a walk in Seattle’s Tashkent Park, former mayor Uhlman and professor Cirtautas look forward to the stsca’s future. “We can learn so much,” says Cirtautas, from Uzbekistan’s “remarkable culture.”

The worn but still-gracious facades of 19th-century and Russian-influenced buildings are overshadowed by modern new construction such as the Amir Timur Museum and the Palace of Forums, Tashkent’s International Congress Hall. Bustling neighborhood bazaars with more than 3,000 vendors offer beautifully displayed rows of exotic spices, Tashkent’s famous melons, fruits and vegetables, meats, nuts and seeds as well as carefully arranged stack after stack of the famous Uzbek bread, non.

Independent after centuries of domination, Tashkent has reclaimed and celebrates its history, language and Muslim heritage. “The government paid a great deal of attention to restoring our heritage after the collapse of the Soviet Union,” comments Miliyev, whose own ethnic background is both Uzbek and Tajik. “We have restored most of the historic buildings and recovered the names of Uzbek poets and scientists. I am really proud to be an Uzbek.”

In the evenings, Tashkent’s sidewalk restaurants overflow and families stroll throughout the city. Children play beside the big fountain or dance with street performers in the open square across from the elegant Lotte City Hotel. Along Bratislava Ko’chasi, patrons wander into the Seattle Café and stop for tea. If they are lucky, owner Nazarov will pull out his albums and take them back in time to 1988, when the long distance between Tashkent and Seattle was bridged through friendship.

seattle-tashkent.org

About the Author

Piney Kesting

Piney Kesting is a Boston-based freelance writer and consultant who specializes in the Middle East.

Steve Shelton

Seattle-based multimedia journalist Steve Shelton has covered stories in the US, Middle East, Balkans, Central America and Sudan for a wide variety of news publications as well as nonprofits and commercial clients.

You may also be interested in...

Stratford to Jordan: Shakespeare’s Echoes of the Arab World

Arts

History

Shakespeare’s works are woven into the cultural fabric of the Arab world, but so, too, were his plays shaped in part by Islamic storytelling traditions and political realities of his day.

Family Secret: The Mystery of North Macedonia’s Ohrid Pearls

Arts

Artisans are preserving the elusive technique behind these pearls—handmade from a fish, not an oyster—in a town of Slavic, Byzantine and Ottomon influences.

Nasreen ki Haveli: Pakistani Textile Museum Fulfills a Dream

Arts

Collector Nasreen Askari and her husband, Hasan, have turned their home into Pakistan’s first textile museum.