Egypt Drops the Beat

It was a Cairo composer who produced the world’s first electronic remix, and now, 75 years later, his digital descendants are mixing fresh new beats for new generations. The best place to listen is along the shores of the Red Sea at the annual Sandbox Festival.

It was a Cairo composer who produced the world’s first electronic remix 75 years ago. Today, EDM fans and DJs from across the globe are gathering on the shores of the Red Sea at the annual Sandbox Festival.

In 1944 Halim El-Dabh lugged a suitcase-sized predecessor to the magnetic tape deck, called a wire recorder, to a folk ritual known as a zar.

Although he was studying agricultural engineering at Cairo University, El-Dabh was also a budding avant-garde composer who had grown up amid the Egyptian capital’s flourishing music and recording scene. After the zar, he took the recorder to a nearby radio station in Cairo. There he used echo chambers and voltage controls to manipulate the trance-like vocals, drums and tambourines that lay in the magnetized spool of metal wire. In this way, the world’s first electronic track was born, “Ta’abir al-Zaar” (“Expressions of the Zar,” which El-Dabh later called “The Elements of Zar”). Its haunting synthesized sounds can be found today excerpted on YouTube.

El-Dabh went on to sample everything from scrap metal clangs to qanun, or zither, twangs. Bending, shaping, overlaying in pursuit of what he called “inner sound,” he “looked at sound like a sculpture,” he said in a 2005 interview. A Fulbright scholarship in the early 1950s took him to the us, where he went on to six decades of aural experimentation that often combined ethnomusicology and new technology. Although he remains little known even in Egypt, El-Dabh is generally recognized as “the father of electronic music.”

In the late 1990s, a second Egyptian electro-music evolution arose. It, too, involved students who, like El-Dabh, used the technology of the day—in this case early computers—to sample everything from Bedouin singers to riqs (tambourines) and Western instruments. Many attended universities abroad where they explored the dance beats of house, techno and trance. Degrees were not all they brought home: There were vinyl records, Technics turntables and mixing boards. Electronic raves followed, often advertised on photocopied flyers with an entry password.

Producers Hussein Sherbini and Mahmoud Shiha, both 32 years old, remember the scene.

“As so few people had the necessary music tech, I played my first gig aged 16,” Sherbini recalls. “Laptops were scarce, and we carried my entire computer with a big box screen” into private parties. Because the latest vinyl was hard to come by in Cairo, Sherbini and Shiha figured out how to craft live music on the spot using early versions of the software FruityLoops, which “could synthesize any sound.” They recall that occasionally foreign djs and electronic artists would fly in and play venues barely suitable for a hands-in-the-air stomp. Paul Oakenfold played a private, Nile-side wedding; Seb Fontaine rocked the Sakkara Country Club. The creative influences on Egyptian ears were pretty much one-way from the West.

It was up to pioneers like Sherbini, Shiha and others to start moving them in other directions. Egyptian pop musicians, says Shiha, “have essentially been singing the same song since 1989. So we thought, ‘Let’s open a music studio and see what we can create.’” After a few years supporting themselves with advertising jingles produced in the house of a friend’s grandmother, they opened EPIC 101 Studios in 2011. The location is nothing fancy: It’s an apartment in Dokki, a neighborhood across the Nile from downtown.

Crucially, says Shiha, it had windows facing the street, which meant “we could put our sign in the window rather than on the street, so we pay less taxes,” he says with a laugh. Quotes for soundproofing were extortionate. “So we went on YouTube to learn soundproofing, wiring and glazing and did the lot ourselves.” Success has followed. By creating both sounds and electronic visuals, they won a commission for a Doritos commercial in 2014. Then, in 2015, they produced visuals for top Egyptian pop icon Amr Diab. A more recent job projected animated, psychedelic visuals onto the facade of Cairo’s British Embassy, while a digital avatar of Queen Elizabeth ii waved from a 3-D balcony, all set to throbbing beats.

Other Egyptians began to join the party. EPIC 101 Studios began supplementing production income with courses in dj-ing and composition, as well as visuals production. “Thirteen-year-olds to 50-year-olds, around 800 students in all,” says Sherbini, have shown up. “You need no electronic experience. You just have to want to do it.” Sherbini and Shiha each write and run several courses, while other courses are guest-taught by digital stars like Egyptian electro-chill master Slim Nasr. A new, larger studio is in the pipeline—as are opportunities for the studio’s graduates to perform live—and they are producing free tutorial apps in Arabic.

Word of the scene spread outside Egypt, too. Aspiring djs and musicians from Britain and Germany found EPIC 101’s fees could be as little as one-tenth of the cost of comparable courses at home. The studio’s eight years of business has also paralleled the growth in social media, broadband internet, WiFi and streaming, as well as collaboration music platforms, all of which help them link with artists near and far. Now djs anywhere can find tracks by Shiha and others. New songs are streamed on music-sharing platforms like SoundCloud, Mixcloud and Beatport with no need for recording labels, distributors or industry media buzz. At the same time, the partnerships and influences among Egyptians and other djs were blossoming online, culminating in a plan to find a physical meeting place. The annual Sandbox Festival, a thumping celebration of house and electronic music, was born and is now held every spring in El Gouna, where the mountains of Egypt’s Eastern Desert meet the Red Sea.

As much as El-Dabh’s wire joined acoustic tradition with electronic avant-garde, the highway from Cairo south to El Gouna remixes medieval and modern. In downtown Cairo, hand-painted movie murals compete alongside flashing digital led billboards. Art Deco mansions bestride Mamluk mosques. Bicycle deliverymen take orders by WhatsApp for wicker trays of ‘aysh baladi flatbread that they balance on their heads amid multilane traffic. Young couples wear matching Liverpool FC shirts in homage to local football hero Mohamed Salah who, at age 26, is older than half of Egypt’s 100 million population. Leaving Cairo is a maelstrom of watermelon trucks, upscale Land Cruisers, vintage Beetles, police Jeeps, honking commuters and revving scooters.

Electronic musician Nomad Saleh, 39, is one of the 4,000 global revelers on the road to Sandbox. He opens up on the new 10-lane highway that skirts the site of Egypt’s proposed new capital, which will one day host much of the government alongside artificial lakes, solar farms and a massive theme park. Saleh, who ditched a chemical engineering degree to become an electronic composer and photographer, explains that with high-speed internet and the 2011 revolution, “Egypt is changing fast.” The revolution had a side effect on the music scene when nighttime curfews obliged clubs to stay open until daybreak.

“In electronic music, we have pioneers like djs Aly & Fila, who play all over the world,” he says, referring to the trance duo with two million Facebook followers and more than 200,000 views of their dreamy 2015 set at the Giza pyramids. As he talks, his phone pulses and bleeps from a peer-to-peer app sharing real-time alerts of checkpoints and speed cameras.

“Electronic music has even touched a different social class with mahraganat,” continues Saleh. The word literally translates as “festivals,” although it has evolved to mean an electronic hybrid of traditional shaabi (popular) music from Cairo’s working-class suburbs, often performed with spectacular gymnastic dancing as revelers wave the kinds of flares normally used for roadside emergencies. It took hold in a big way during the 2011 revolution with lyrics often laced with antiestablishment invective, not unlike American hip-hop. Also like hip-hop, mahraganat was at first starved of official airplay, so it spread via mp3 files swapped among basic Nokia cellphones and played in taxis and tuk-tuks. Low-tech YouTube tracks that didn’t use video at all still attracted tens of millions of views. Would Saleh attend a mahraganat gig? “Probably not,” admits the musician. “Our scene is very tribal.” But since the revolution, tv ads have used mahraganat to sell washing machines and car insurance. Even dj and superstar performer Diplo jetted over in 2017 from Los Angeles to meet rough-hewn singers in Salam City—an ungentrified district that the Egyptian Tourism Authority prefers to ignore.

Saleh’s own interests tally with this emerging electronic role reversal: Western musicians are flying to Egypt in search of everything from inspiration to innovative riffs to lay over beats. After turning right near Suez, Saleh Bluetooths a chilled oriental collaboration with the French group, Pandhora. “These guys wanted an immersive experience, so I took them to Siwa,” he says, describing the oasis of palms and canals deep in Egypt’s Western Desert. There, Saleh matched their MacBook Pros and Akai Force synthesizers with traditional instruments. “It was basically a one-week jam lit by lanterns and shooting stars,” Saleh recalls. The forthcoming album is simply titled Siwa. They tweaked the production online by sharing the audio files. When they decided they needed a backup singer, Saleh commissioned a Cairene songstress. Did Pandhora meet her? “There was no need.” Did Saleh meet her? “Only on WhatsApp.”

As the sun sets behind the Red Sea highway, ridges and sand go ochre. Twinkling offshore oil rigs become stars on a calico stage under a moonlit, still-blue sky, like the world has just turned upside down. The road ends in El Gouna, where Egypt’s leading electronic musician is also flipping music production on its head.

Cairo-born dj Safi is the godfather of contemporary Egyptian electronica. More importantly, the 39-year-old is pushing international collaborations to new levels. With a goatee beard and a Zen-like persona, he presides over the Düf recording studio like a space-age monk. The studio fully opened earlier this year, but Safi had already made his first commercial venture at 10 years old mixing tracks on cassettes he sold to friends “for three days of lunch money.” Yet like so many musicians in Egypt, his career was interrupted by seven years of medical school. “There’s a subconscious social element in my generation that has trapped so many creative Egyptian minds in engineering degrees or similar. Although attitudes are changing,” he says, “if you got good grades in high school and told your parents you wanted to become, say, a photographer, you might get slapped.”

His chance to deep dive traditional Arabian sounds came in 2007. Safi pioneered a radio show at Nile FM called Nile Bazaar, which fused Western beats with Eastern melodies, as well as HomeGrown, a show that allowed local musicians to have their tracks played in high rotation. “It’s common in Egypt to copy and promote yourself as, say, a Pearl Jam cover band. With respect, you won’t become the next Pearl Jam, but if you add a bit of tabla and ‘ud, that could take your sound all over the world.”

Safi is also grafting East onto West in another way. “I say to visiting artists, why not work on music during the winter rain when you can make tunes here at Düf with your family, like a musical staycation?” Most European and American artists visit to find sounds they can’t find at home—not only in terms of traditional Egyptian instruments. “When these foreign artists fly in,” says Safi, “I might inspire the group by sailing out to sample some Red Sea dolphins, then we’ll go and make a track. Then musicians’ eyes really light up!” He recounts that when New York-based dj duo Bedouin came to El Gouna, he laid on a surprise. “I asked them, ‘Has Bedouin ever been in a studio with real Bedouins?’” They had not. “So I brought in a whole group of cats from Upper Egypt who have installed pickups on their rubabas,” he says, referring to the traditional, stringed instrument.

Money remains a push and pull for musicians in Egypt and throughout the Middle East. For some, like veteran Jordanian dj Kitchen Crowd, it’s less expensive to live and rent studio time in El Gouna than it is to stay at home in Amman. On the flip side, the Egypt Musicians Syndicate charges fabulous fees for foreign musicians to perform in Egypt, be they Syrian,

German, Tunisian or American, thereby holding back a potential United Nations of musical performance. There are difficulties going the other way, too. “Next month I got booked in Tunis,” explains Safi. “But when I looked at the paperwork for an Egyptian to apply for a Tunisian visa, it was just too much.” He says he hopes technology will break down some of these barriers, too, as it has already done for others.

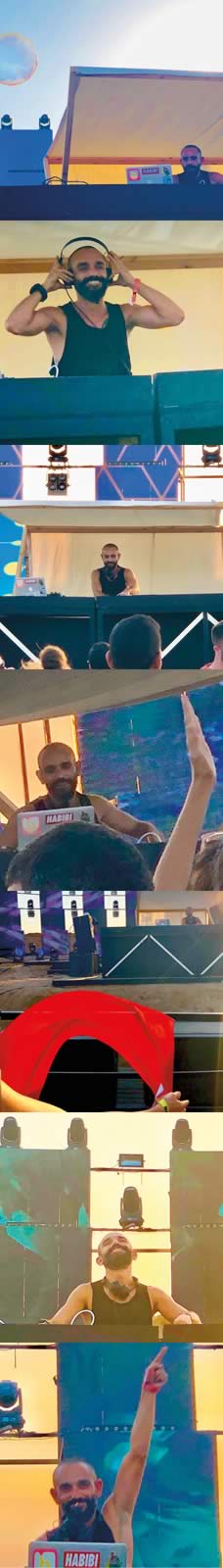

The following day, few barriers are holding back the Sandbox festival. Uber tuk-tuks ferry a Day-Glo army of fans to a few hundred meters of beachfront at the edge of town. Kites pulling kitesurfers float offshore like Technicolor butterflies, and the arena is half Mad Max with sand bulldozed into high berms that wrap the festival’s two soundstages. A hypnotic bass line tremors the sand underfoot. A 21st-century arcadia awaits behind the festival gate, though compared to other world megafestivals, it is boutique: a motel-sized cool-off pool, a pair of wooden swing sets, a scattering of seesaws and giant capital letters spelling “SANDBOX” are all live selfie bait. Swimmers in the Red Sea’s shallows limber up before a sunset shimmy. The beat is about to drop.

The opening sets of late afternoon are smooth and sirenic. Then the sun blisters gold, crashes behind the distant ridge, and the tempos pick up, unleashed, rumbling, whipcracking into hyperwarps. Arms fly up, brows glisten, and communal euphoria sweeps the transnational, multigenerational crowd. Behind the decks is 32-year-old Cairo-based dj Zeina, who studied music production both in Canada and at EPIC 101. The latter’s Sherbini and Shiha are nearby, running their studio’s pop-up stage backed with floor-to-ceiling light panels. Theirs is a stage where anyone can come play with the drum machines, keys and midi boards, the better to entice a new generation of artists. Nomad Saleh shares the party from a bespoke Instagram photography tent.

Safi is there too, confessing to the nerves he says always come before performing. His set, splicing Egyptian and European house sounds into unique musical dna, is on in two days. “I asked to play as the sun was setting,” he says. “I like the challenge of a set that bridges the day and the night.”

After her set, Zeina is all smiles. Like every Egyptian electronic musician, she is by necessity a trailblazer, running an all-female dj night in Cairo plus a production operation. “The constant narrative that outsiders want to paint is one of how it’s a struggle for female djs,” explains Zeina. “That can get repetitive. Instead it would be insightful to discuss our creative process as artists, as our scene is growing fast.” (Students in EPIC 101’s courses in live visuals production are predominantly female.) “The club circuit can get exhausting,” she continues. “So sometimes the ability to be confined to a studio space, where I’m answerable to me, myself and I, is the perfect antidote.” But Sandbox won’t be Zeina’s only summer gig. She’s playing near Alexandria a party jointly organized by Lebanese outfit Überhaus and London-based Boiler Room, which puts on dance music events as far as Berlin, Lagos, Ibiza and Ramallah, Palestine.

“Their Ramallah party [in 2018] was actually Boiler Room’s best performing event,” explains Zeina. “It’s because people are so curious to see what the Palestine scene looks like.” In addition to a lineup of other top Palestinian djs and musicians, it was topped by techno queen Sama’, who trained in Cairo as an audio engineer before becoming Palestine’s first female dj and electronic producer.

“This is about taking Egyptian dance culture to the rest of the world,” says journalist Russell Beard, who last year flew from his home in Scotland to emcee the festival’s official video. “This is in the process of emerging, connecting up to a global scene.”

With the mixing of music comes the mixing of people, networks and ideas. Chats over smoothies and sushi deep into the festival nights might cover samples, mixes, venues and introductions to new artists. Beanbag conferences on the beach may hatch recordings in El Gouna, London or online. Festivalgoers sharing #sandboxfestival tens of thousands of times showcase over and over the still largely underground talent—all notes in a beat that’s been building ever since Halim El-Dabh walked out into Cairo carrying his wire recorder 75 years ago.

About the Author

Rebecca Marshall

Rebecca Marshall is a British editorial photographer based in the south of France. A core member of German photo agency Laif and Global Assignment by Getty Images, she is commissioned regularly by the New York Times, Sunday Times Magazine, Stern and Der Spiegel

Tristan Rutherford

Tristan Rutherford is a 7-time award-winning journalist. His writing appears in The Sunday Times and the Atlantic.

You may also be interested in...

Zakir Hussain Played Tabla in Indian Classical Music and Beyond

Arts

While mastery of Indian musical traditions is one clear accomplishment, the late Zakir Hussain’s bold pursuit of his art across genres likely best defines his legacy.

Orion Through a 3D-Printed Telescope

Arts

With his homemade telescope, Astrophotographer Zubuyer Kaolin brings the Orion Nebula close to home.

How South Africa Came to Popularize Luxury Mohair Fabric Globally

Arts

South Africa is the world’s largest producer of mohair, a fabric used in fine clothing. The textile tradition dates to the arrival of Angora goats from the Ottoman Empire in the 1800s.