Hassan Hajjaj's Hot Remix

With brilliant colors, bold patterns and unbridled exuberance, photographer and designer Hassan Hajjaj has become one of the world’s most popular artists, remixing esthetics from Marrakesh to London, from heritage to hip-hop, with a playful, subversive swagger.

Noss-noss.

That’s how Hassan Hajjaj has been described. It’s an Arabic term that literally translates as “half-half.”

“My work is from Morocco and London,” he explains.

But like many shorthand terms, noss-noss, which he also chose in 2007 as the name for his first solo show—can be more complicated. Moroccan by birth, Hajjaj has lived in London since he was 12, and the city remains his principal home.

“I see myself as a human being first, and then as a Moroccan, a North African, and as a Londoner, not British,” he emphasizes, “a Londoner.”

But like many shorthand terms, noss-noss, which he also chose in 2007 as the name for his first solo show—can be more complicated. Moroccan by birth, Hajjaj has lived in London since he was 12, and the city remains his principal home.

“I see myself as a human being first, and then as a Moroccan, a North African, and as a Londoner, not British,” he emphasizes, “a Londoner.”

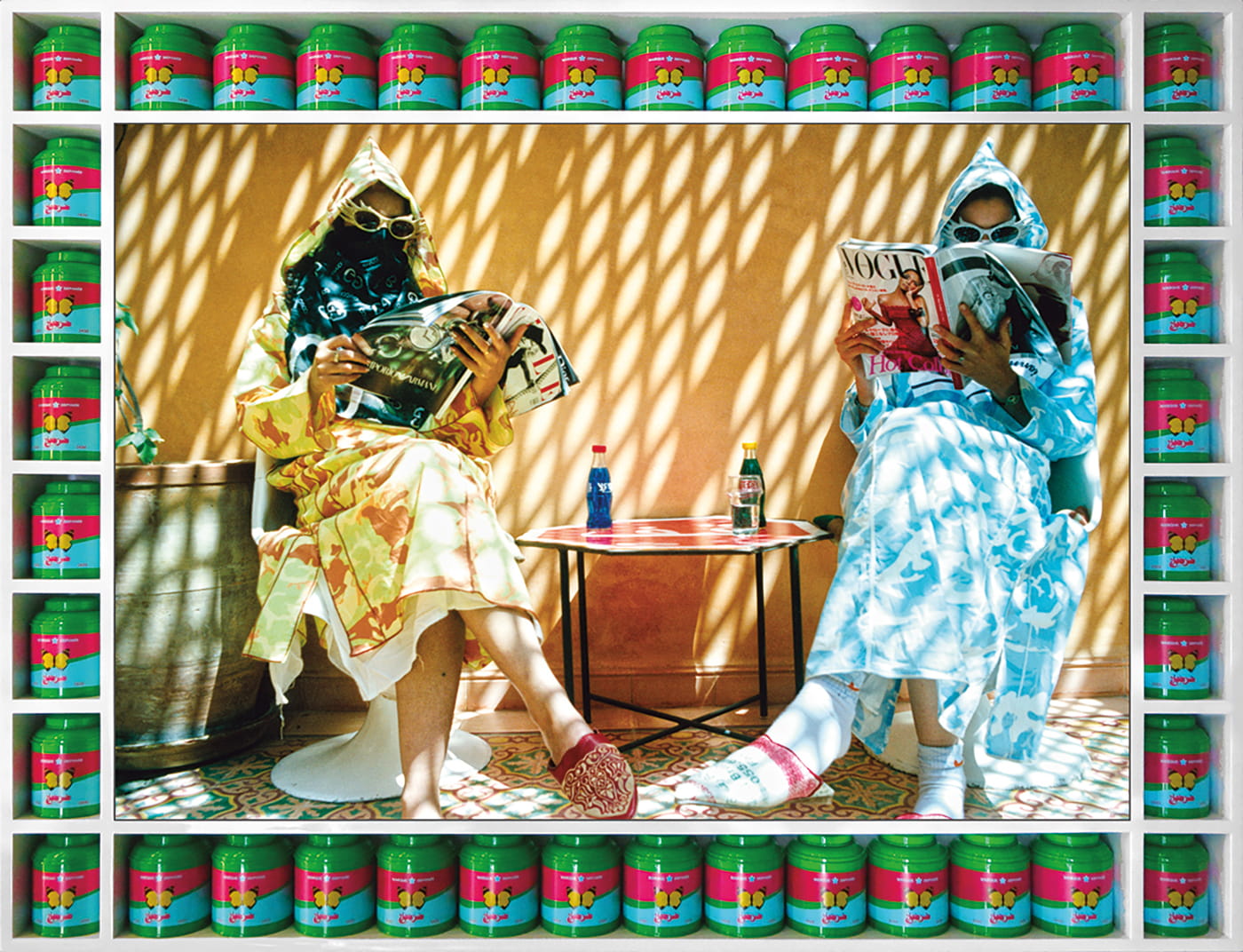

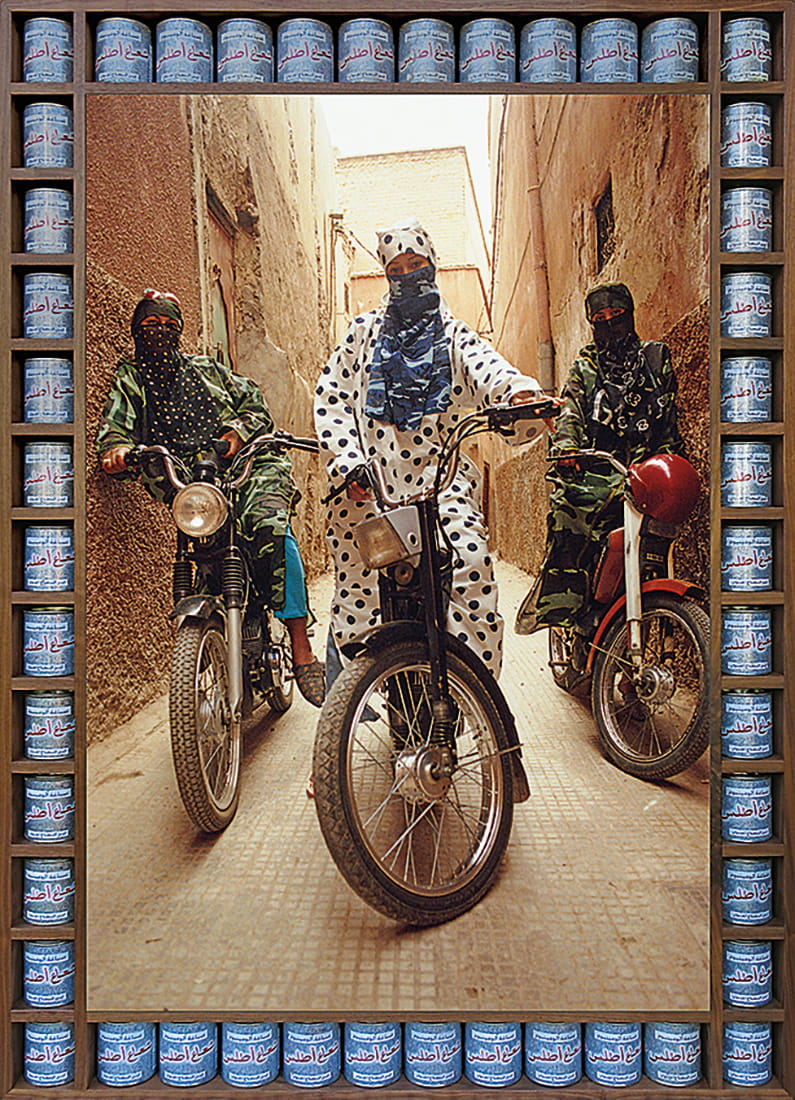

“Time Out,” Vogue, the Arab Issue series, 2007/1428, framed photography.

As an artist, he is before anything else a photographer, but one who also designs funky fashion and furniture that supports Moroccan artisans through boutiques in London and Marrakesh. He produces videos and the occasional sculpture installation, too. He encourages traditional Moroccan artisans to experiment with playful, contemporary, pop-influenced touches such as solid and patterned Day-Glo colors.

His photography is an essentially urban art, rooted in popular culture that remixes visual elements of fast-evolving subcultures from Arab and sub-Saharan African to hip hop, consumerism and high fashion. Always exuberant, sometimes challenging—and frequently both—he freely blends heritage and pride with street style and swagger. Though he avoids the explicitly political, his images are tinged with gently subversive, often light-hearted social satire on issues such as gender expectations, cultural appropriation and the ambiguities that come with noss-noss identities. Hajjaj’s response to his own Moroccan noss, he says, is to celebrate in particular its inner-city aspect, “the glamor of its street fashion, the energy, the attitude and the inventiveness of its people, as well as the fantastic graphics of everyday objects and products.” This, he explains, dates back to 2000, when his work on a documentary called Pop Art in the Kasbah inspired a photographic series on street iconography of Marrakesh, Graffix from the Souk, which was shown in London that same year.

His unique blend of pop-art esthetics, in particular his embrace of iconic consumer brand labels and North African culture, has led more than one observer to dub him “the Moroccan Andy Warhol,” a label he refutes.

“People say that,” he says, “but it’s really a label the West has given me, because the West controls the art world. We have to fight extra hard as non-Western artists because of these labels.” Nevertheless, his spirit of mischievous reappropriation often wins out: Hajjaj designed a bar in Paris named Andy Wahloo. In Northern African Arabic dialect, wahloo translates “I have nothing,” and Hajjaj still uses Andy Wahloo as a tongue-in-cheek trademark for clothes and installations.

His photography is an essentially urban art, rooted in popular culture that remixes visual elements of fast-evolving subcultures from Arab and sub-Saharan African to hip hop, consumerism and high fashion. Always exuberant, sometimes challenging—and frequently both—he freely blends heritage and pride with street style and swagger. Though he avoids the explicitly political, his images are tinged with gently subversive, often light-hearted social satire on issues such as gender expectations, cultural appropriation and the ambiguities that come with noss-noss identities. Hajjaj’s response to his own Moroccan noss, he says, is to celebrate in particular its inner-city aspect, “the glamor of its street fashion, the energy, the attitude and the inventiveness of its people, as well as the fantastic graphics of everyday objects and products.” This, he explains, dates back to 2000, when his work on a documentary called Pop Art in the Kasbah inspired a photographic series on street iconography of Marrakesh, Graffix from the Souk, which was shown in London that same year.

His unique blend of pop-art esthetics, in particular his embrace of iconic consumer brand labels and North African culture, has led more than one observer to dub him “the Moroccan Andy Warhol,” a label he refutes.

“People say that,” he says, “but it’s really a label the West has given me, because the West controls the art world. We have to fight extra hard as non-Western artists because of these labels.” Nevertheless, his spirit of mischievous reappropriation often wins out: Hajjaj designed a bar in Paris named Andy Wahloo. In Northern African Arabic dialect, wahloo translates “I have nothing,” and Hajjaj still uses Andy Wahloo as a tongue-in-cheek trademark for clothes and installations.

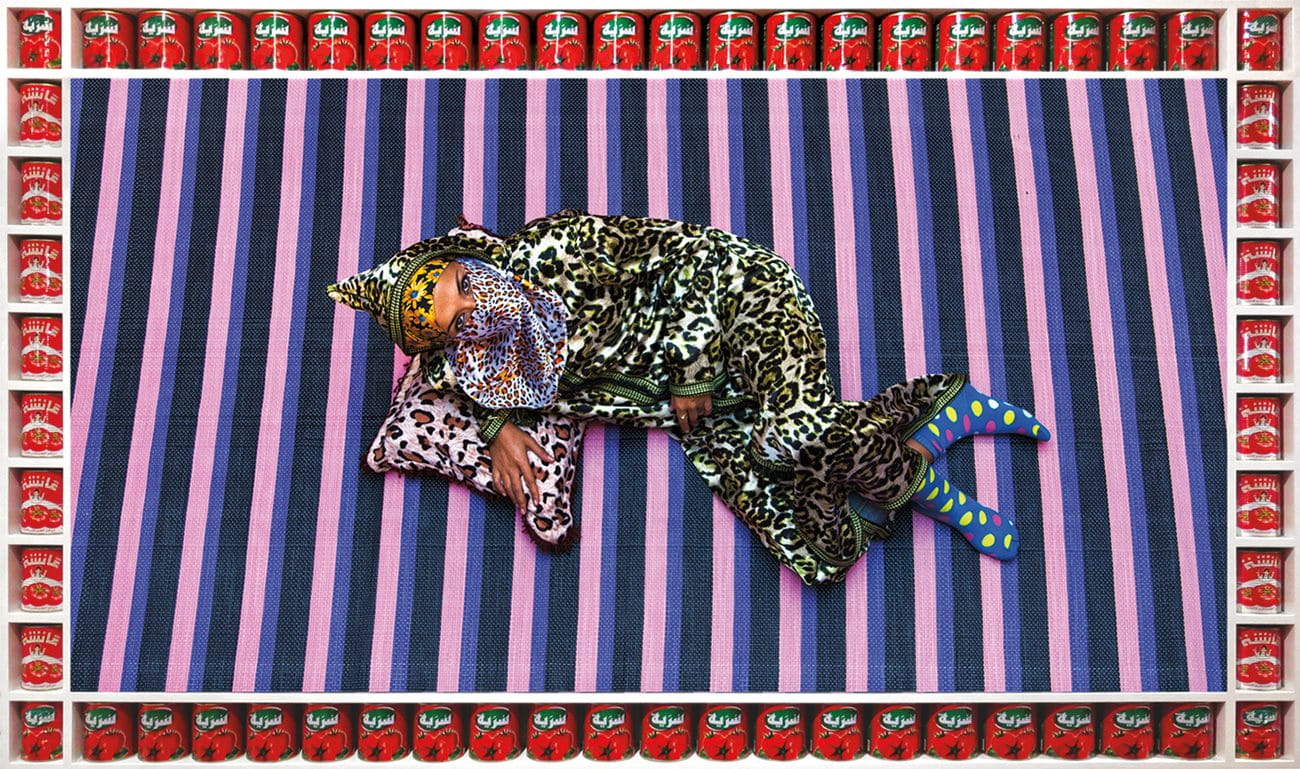

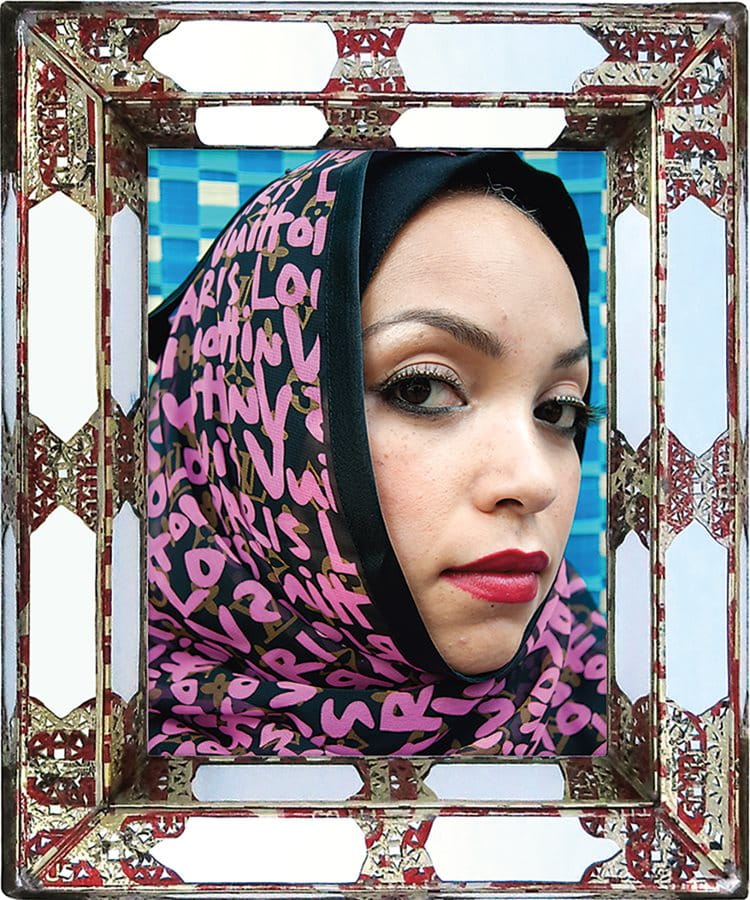

"Alia Ali,” untitled series, 2014/1435, framed photography.

Dress with zebra motif, amber beads and fez, Riad Yima, Marrakesh.

On display were Hajjaj’s most important photographic series, video works and sculptural installations, including Dakka Marrakshia; Handprints; Kesh Angels; Gnawa Riders; Hand-painted Portraits; Vogue, The Arab Issue; Legs; Graffix from the Souk, and My Rockstars.

Even the MEP’s normally sacrosanct bookshop became a Hajjaj boutique selling his furniture, homeware and clothes, many of them designs based on the Moroccan djellaba (robe) and babouches (slippers). In depicting them, Hajjaj debunks cultural clichés such as camels and veiled women. “Moroccan women are so strong,” he says. “The veil is still worn because of tradition; it’s their heritage. I’m not putting women behind veils to repress them. In fact there’s still flirtatiousness behind it in my photographs, and I’m trying to emphasise the mischievous aspect. It’s double-edged here now. Look how modern and defiant they are,” he adds. “They’re blending tradition with pop fashion.” Indeed, last year both in Paris and in Marrakesh he invited young, and especially female, photographers to exhibit in the same venues as his own shows.

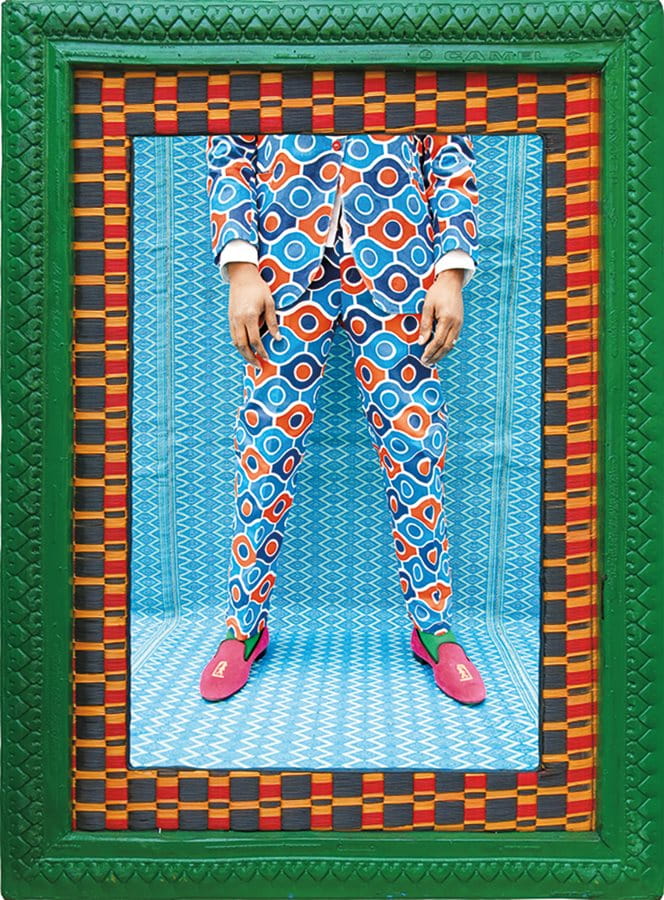

"Joe Legs,” Legs series, 2012/1433, framed photography.

This year, part of that same Paris exhibition traveled to Stockholm as Vogue, the Arab Issue, and if global health conditions permit, it is scheduled to show in New York in September. Clearly ironic, the name of this series appropriates and reinterprets the iconography of decades of fashion shoots by Western photographers using Western models wearing Western clothes in “exotic” locations—like the madina, or old city, of Marrakesh. In Hajjaj’s iconic image of the series, two Moroccan women sit coolly reading Vogue and Elle through cheap plastic, comically wing-tipped sunglasses, bottles of Coca-Cola set on the table between them.

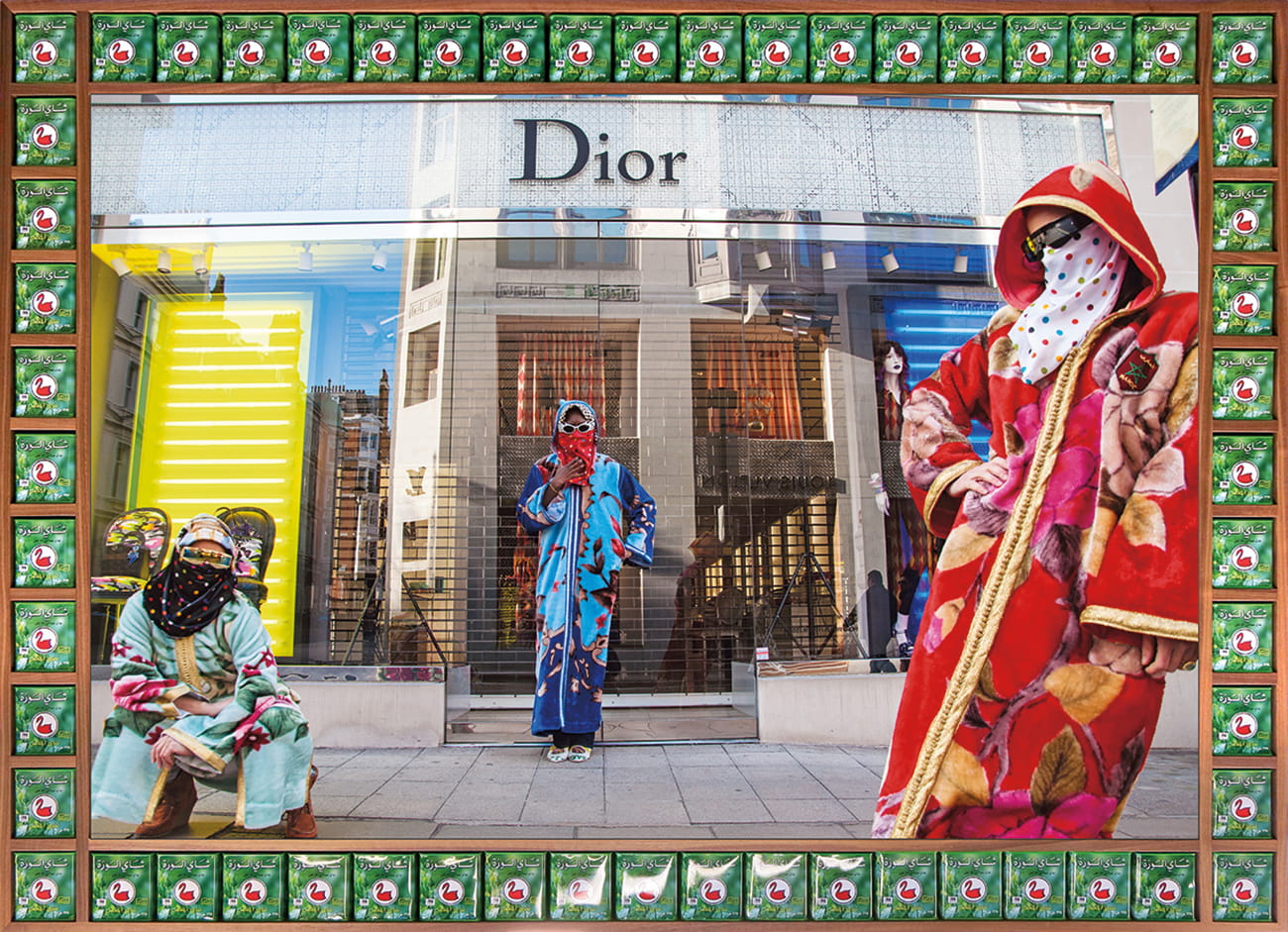

In this series as in his now-famous Kesh Angels, the models are dressed in kaftans and veils of counterfeit material printed with internationally recognized brand logos such as Chanel, Gucci and Louis Vuitton, plus traditional Moroccan slippers stamped with Nike or Adidas. The two series show how fusions of traditional and contemporary style can be hip and fashionable. The irony is extended by locating some of the images in front of actual Chanel and Dior shops in London’s elite Bond Street. “When my friends and I were growing up, of course we weren’t able to wear real brands,” he says. “These imitations of brand names were aspirations. They represented hope.”

“Hajjaj belongs to that generation having grown up within the paradoxes of post-colonial social and historical conflicts. But rather than seeking confrontation, he defuses the impact of those conflicts by extolling the hybridity and multiculturalism that make him who he is.”

—Rose Issa

—Rose Issa

So how did his journey from Larache, the small fishing town in northern Morocco where Hajjaj was born in 1961, blossom into global art recognition? In 1973, aged 12, he left Morocco, which was suffering harsh economic times, together with his family to join his father, who could neither read nor write, in London.

“I found London difficult, strange and sad,” says Hajjaj. “It was a really tough time.” Arriving speaking only Arabic and French, he dropped out of school at 15. “I spent some troublesome years trying to fit in and figure out what it meant to be a streetwise Moroccan in London during the ’70s.” Odd jobs followed just as London was becoming ever more of a vast cosmopolitan remix of the cultures of the former British Empire, including Caribbean, Asian as well as African, all striving to assert themselves in the socially constrained, class-bound society of that era.

“We’re people who’ve been moved around a lot, some centuries ago, or like me, recently,” he says. While some confronted this militantly, others like Hajjaj embraced a multicultural alternative lifestyle defining themselves in music, fashion, and cinematic and visual arts. It was an essentially metropolitan, affirmative culture that rejected victim identity, one that has deeply influenced uk society to this day.

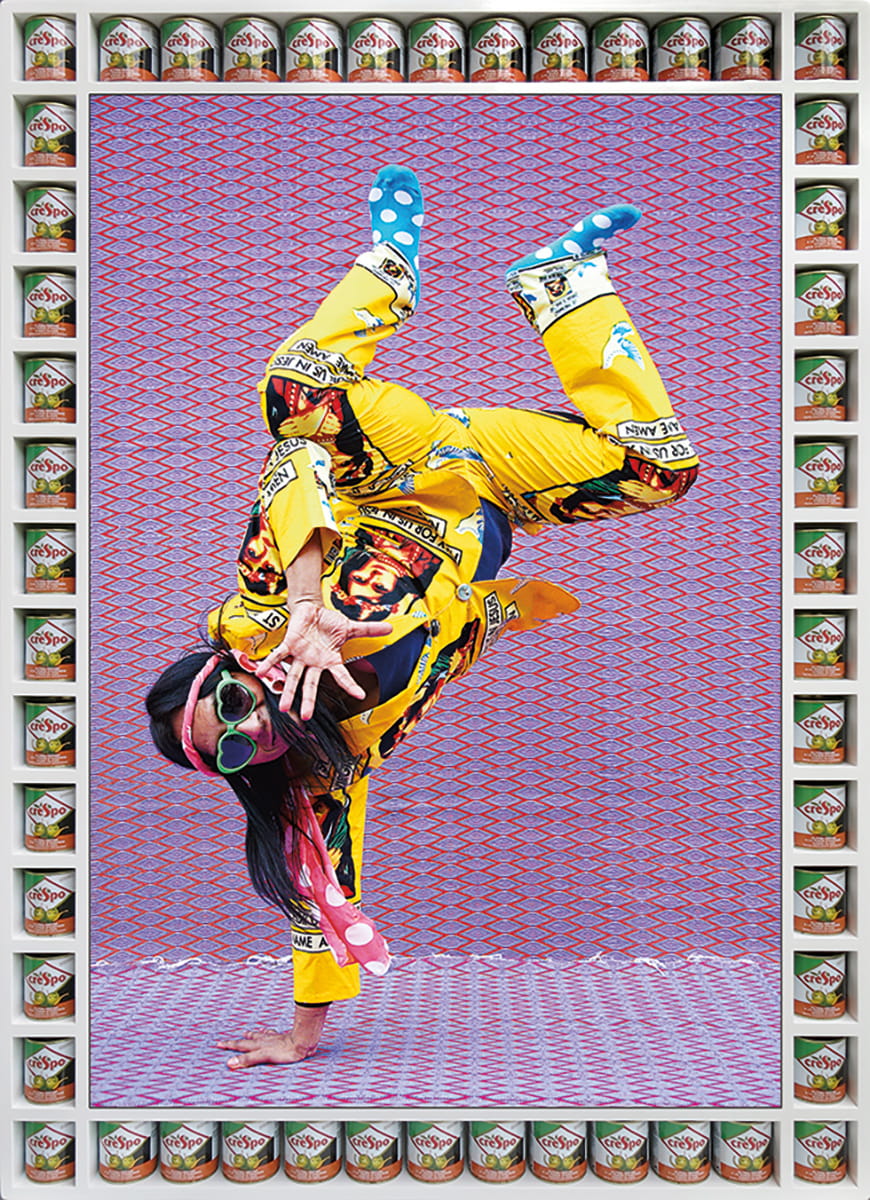

“Rilene,” My Rockstars series, 2013/1431, framed photography.

Initially, RAP's customers were friends and fellow creatives striking chords on the alternative scene who revelled in his fresh mix of logos and ethnic influences fairly vibrating in the clothes. It wasn’t long until RAP became the funky hangout.

Simultaneously Hajjaj began working with filmmakers, taught himself photography and started using those images to celebrate his noss-noss identity. The results created a world Krifa describes as “an unashamedly glamorous pop aesthetic, the visual equivalent of the samplings, mixing and blending essential to popular music since the birth of hip-hop.”

But as yet, his photographs had not been published. Rose Issa, an independent London curator and one of the city’s leading promoters of Arab arts and film, having known him as a friend for more than 15 years, one day received an unexpected phone call.“

He wanted to show me some of his photographs,” she recalls. And so, in predigital 2006, Hajjaj arrived at Issa’s gallery with a battered suitcase packed with contact sheets and prints he had kept secret for years, until he was ready for this body of work to be shown to the public. It was, Issa says, an astounding amount of work. “No full-time artist or young photographer that I knew had gathered as many images.”

Dakka Marrakashia (Marrakesh Beat) was the result of that meeting and his first solo exhibition in the UK, in 2008.

“Rose was the first person who understood my work,” says Hajjaj. “She was the one who opened doors for me, intellectually and businesswise to appropriate collectors, art galleries and auction houses.” She comments that Hajjaj “loves and has compassion for the underprivileged, ordinary people, incorporating their first-hand experience of street life into his work. These young Moroccans sometimes look menacing but have a smile in their eyes.” Indeed, one of the women who posed for his Kesh Angels series winks at the viewer above her veil. Another shows a bit of leg astride a motorbike. Issa continues: “They are free of tragedy, ideology and morality. But they are defending their world, their turf, their style and their right to have problems and aspirations. Like the artist, they have guts and attitude, expressing black power, Arab power, pride and joy in being streetwise.” However, many of them eke out a living painting designs on the arms, legs and backs of tourists using henna dye.

“Odd 1 Out,” Kesh Angels series, 2000/1421, framed photography. “I plan the shoot with the sitter, but then I always let loose and see what happens,” Hajjaj says.

These young women are Hajjaj’s friends, on whom he based another empathetic enterprise, Karima: A Day in the Life of a Henna Girl, a documentary film that premiered in 2015 in Los Angeles and a year later at the British Museum.

Earlier, in 2010, Issa mounted another solo photographic show of one of his most famous series, Kesh Angels, celebrating the biker culture of young women who ride the streets of Marrakesh on scooters and motorbikes. She describes the highlight of the exhibition as an installation of Hajjaj’s customized motorbike “covered in fashion logos and kitscheries” like the clothes, veils and slippers of the “angels” themselves, which he had designed.

Another signature aspect of Hajjaj’s work is the way he constructs frames to display his photographs. “I love Arabizing them in a cool way. Growing up in Morocco, recycling is something that comes naturally. Mothers make cans into mugs. My frames contain Arab products, such as tins of olives and sardines. This creates a potentially kitschy, humorous effect, and sometimes the frames create repeating patterns, like our mosaics. They also include what were to us desirable brands like Coca-Cola, the bottle tops referencing symbols of international consumerism.

“When I started to show my work, the frames were intended to bridge the two worlds, East and West, and make the photos come alive. Now they are much more global, so if I’m photographing a Nigerian, I try to find something Nigerian to put in the frames,” he said.

Just as he did first for his RAP shop, wherever he travels, and of course in Morocco, he scours markets for cheap materials, clothes and backgrounds for his shoots, which are always in streets, not in studios. “When people don’t have anything, they have to make something out of nothing. How can they still stand out, look grand?” And grand and glamorous they do look. “For people on our continent who don’t have money, looking great alleviates the pain of poverty. And this becomes street chic.”

“Dior,” Vogue, the Arab Issue series, 2012/1433, framed photography.

Full of brilliant colors and objects from custom-made crafts to recycled bottle crates and other

“found objects,” Riad Yima in Marrakesh serves as one of Hajjaj’s two retail boutiques as well as a cafe and gallery.

“found objects,” Riad Yima in Marrakesh serves as one of Hajjaj’s two retail boutiques as well as a cafe and gallery.

Hajjaj has similar though smaller premises in Shoreditch, the newly go-to East End of London. Inside, seating is on upturned, red plastic crates, which once contained globalized consumer goods like Coca-Cola, often printed with Arabic calligraphy. They’ve been given new life as usable furniture, topped with cushions across which a velvet camel may nonchalantly step, or brightly printed flowers trail. Road and shop signs are reappropriated as tabletops. Product tins are repurposed as light fixtures. This remixed art and post-consumer recycling celebrates discarded items, essentially a new take on the culture of the poor, as opposed to an Orientalist viewpoint in which 19th-century Western artists depicted sumptuous, often imaginary traditional Arab interiors. “For me, being Moroccan, it’s taking ownership, control of that fantasy idea and giving that back to our own people,” says Hajjaj. Indeed, in 2012, Issa presented his solo exhibition, ReOrientations in Brussels.

Such is the global reach of Hajjaj’s creativity, it has placed him, as Krifa observes, “at the center of a genuine movement, driven forward by interdisciplinary and international artists, both known and lesser known, together forming his circle of friends.”

Some of these friends have become Hajjaj’s subjects in his ongoing series titled My Rockstars, photographed over a decade primarily in the streets of Marrakesh, London, Paris, Los Angeles, Dubai and more. Each portrait is characterized by warm, loyal empathy. There’s Kezia Jones, a Nigerian hardedge funk singer/songwriter and global luminary, and there’s also Che Lovelace, a little-known Trinidadian conceptual artist. “They’re a blend of people I believe in,” Hajjaj says. These include Gnawa musicians, whose presence in Morocco is due to their forced removal as slaves from sub-Saharan Africa, whom he has been photographing for some time, together with exponents of capoeira, a Brazilian form of self-defense Hajjaj has been practicing since 1990. Capoeira also comes from African roots, and it originated among those enslaved in Brazil.

“Gretchen,” My Designer Hijabs series, 2012/1433, framed photography.

Growing up, he says, he and his friends never went to museums or art galleries because they felt uncomfortable there. He says he wants his work to speak to people like that. “My work is about people, the same kind of people as me. I’ve always tried to present local events for British people in schools and other institutions,” such as Le Salon, a Moroccan installation with live art and fashion, as well as classes for music, dance and henna body painting. New series of work in progress include his photographs of women who pick potatoes in the north of Morocco, acrobats in Tangier and women refugees in Beirut.

“I want my photography to communicate with somebody like myself, who originally wouldn’t go to a gallery, as well as somebody who’s an intellectual,” he says. “I want it to appeal to everyone, whether they’re a cleaner or an art critic.”

You may also be interested in...

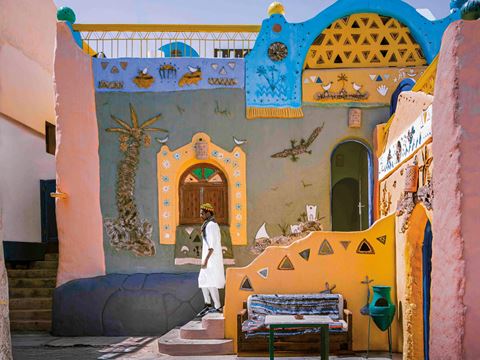

Saudi Photographer Captures Aswan's Nubian Heritage

Arts

As a Saudi photographer with a passion for cultural, human and heritage themes around the world, I strive to make my images windows to the past as well as reflections of the present. When I came across this guesthouse on a visit to Aswan, Egypt, I was taken back to 3000 BCE to ancient Nubia.

Ambon Island, East Indonesia by Hengki Koentjoro

Arts

This photo was taken off Ambon Island, East Indonesia in 2010. It is one of my favorites, illustrating the free-spirited nature of the children in the rural archipelago. While some children in the big cities may stay inside and play computer games, the children in Ambon with easy access to the water see the ocean surrounding their village as their playground.

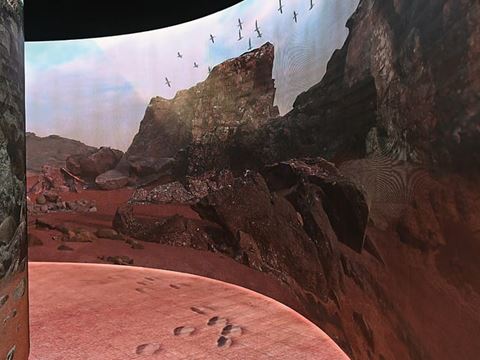

Ithra Explores Hijrah in Islam and Prophet Muhammad

History

Arts

Avoiding main roads due to threats to his life, in 622 CE the Prophet Muhammad and his followers escaped north from Makkah to Madinah by riding through the rugged western Arabian Peninsula along path whose precise contours have been traced only recently. Known as the Hijrah, or migration, their eight-day journey became the beginning of the Islamic calendar, and this spring, the exhibition "Hijrah: In the Footsteps of the Prophet," at Ithra in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, explored the journey itself and its memories-as-story to expand understandings of what the Hijrah has meant both for Muslims and the rest of a the world. "This is a story that addresses universal human themes," says co-curator Idries Trevathan.