Tinariwen's Sahara Blues

Coming out of the struggles of post colonial desert Africa, Tuareg band Tinariwen adapted blues rock ‘n‘ roll guitars to North African traditions. The result has been nearly four decades of a sound that has inspired an entire genre of “desert blues,” in which themes of loss, home, hope and unity transcend language for audiences around the world.

With droning electric guitars and gravel-voiced lamentations, the collective of Malian Tuareg musicians named Tinariwen—pronounce it tee-NAH-ree-wen—has risen to become one of central Saharan Africa’s global voices and a pioneer of a new musical genre. Made up of some 20 guitarists, composers and various accompanists, the band traces its origins to a young Tuareg refugee and musician named Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, who in 1979 began singing and composing guitar-based songs in Algeria’s southernmost city, Tamanrasset.

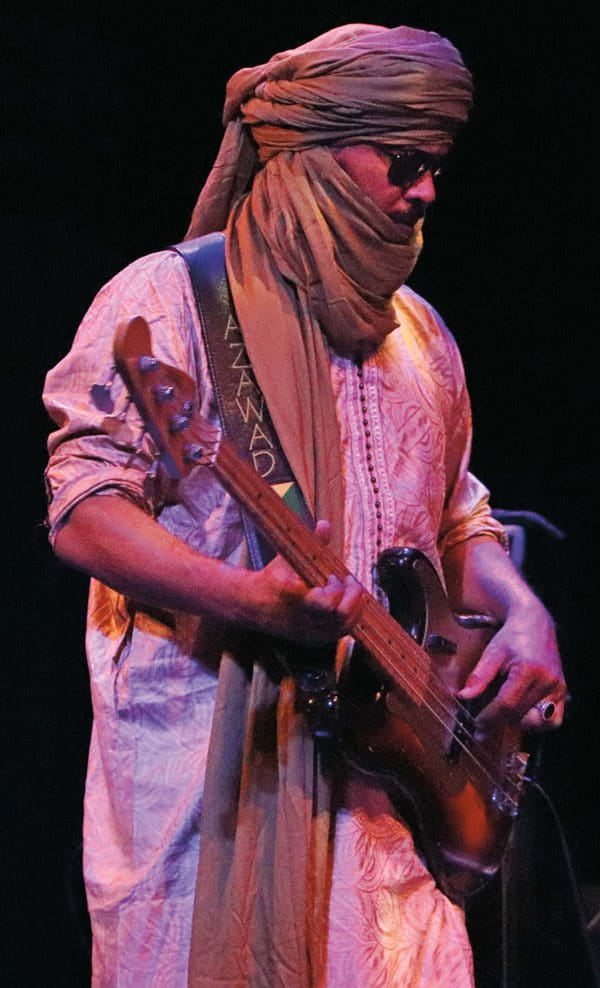

His socially aware lyrics expressed Tuareg identification with other indigenous inhabitants of North Africa, mainly Amazigh (Berber) peoples. Throughout the southern and western Sahara, centuries of Tuareg pastoralists and nomads have moved with herds and caravan traders, and the Tuareg became known to outsiders mainly by distinctively deep-blue, indigo-dyed headscarves. Since the postcolonial independence movements of the 1960s, Tuaregs have lived mostly among four countries—southern Algeria and Libya, as well as northern Mali and Niger—where decades of desertification and conflict have given another meaning to blue.

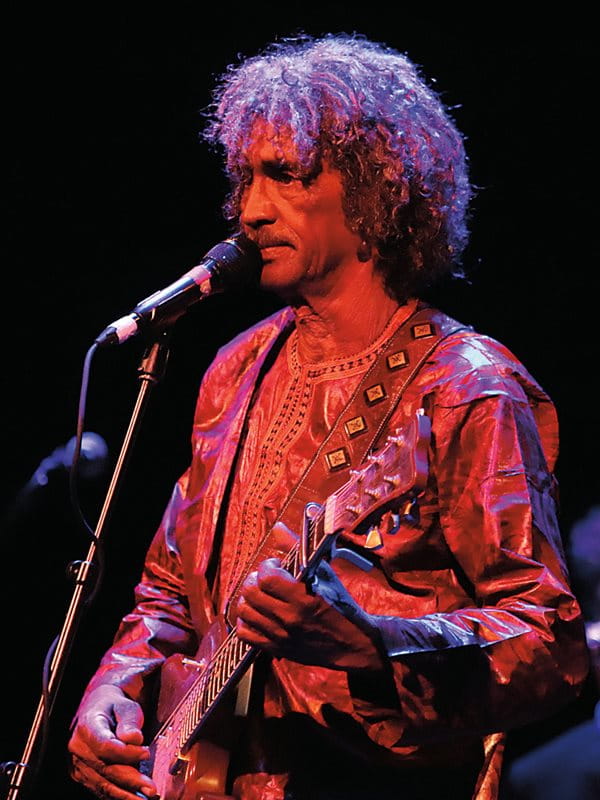

Guitarist, singer and composer Abdallah Ag Alhousseyni is Tinariwen’s principle spokesman. Born to a nomadic family, he arrived in Tamanrasset, long a crossroads for Tuareg clans, as a young man in 1982. The city then had a population of around 70,000, and Alhousseyni recalled, in a telephone interview in 2004, how already “Ibrahim [Ag Alhabib] was a celebrity,” and it was the place to find cassettes of Bob Marley, Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, John Lee Hooker, Dire Straits and others. These tapes had been finding their way into the desert for a long time, he said. When local musicians started playing guitars, they had influences from all these genres of music, and also Maghrib music from Morocco and Algeria, like Nass el Ghiwane and Jil Jilala, he said. “In the quarter where I stayed … there were a lot of young people nearby, my neighbors, who listened to the same songs.”

The name Tinariwen means “desert people” in the Tuareg language, Tamasheq. Officially, the band formed in 1985—not in Tamanrasset, but in a military camp in Libya, where its core members had joined the on-and-off conflict with the Malian government that had begun in the early 1960s. Alhousseyni had already been listening to Tinariwen cassettes when, at a rebel camp in Libya, he met Alhabib and the rest of the new band. They welcomed Alhousseyni as both a musician and a soldier.

The band recorded its early music in makeshift studios and even around campfires in the open desert. It produced cassettes locally and distributed them clandestinely. The songs resonated with Tuareg youth because they paired worldly, plugged-in musical sounds with acute social and political realities. Lyrics of longing, loss, separation and faith in the face of hopelessness—classic themes in blues as well as Tuareg poetry—resonated, too, and all the more so when entwined in Tinariwen’s bluesy tangles of guitar lines that also reflected North African rhythms and vocal styles.

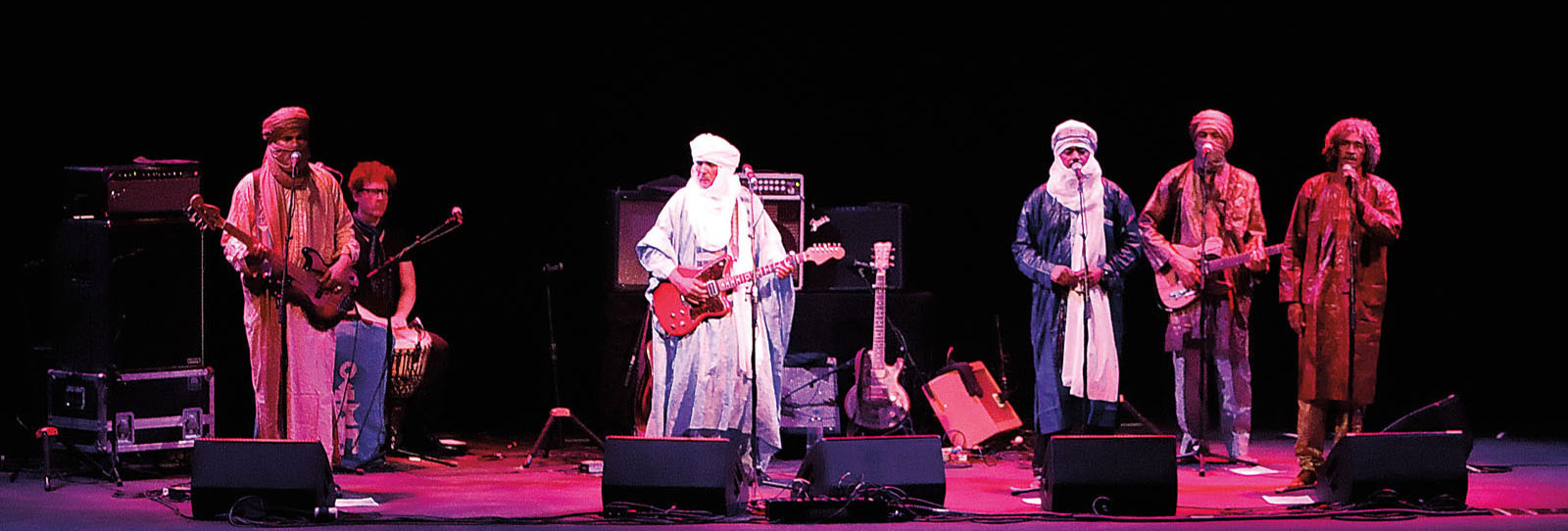

In September, Tinariwen performed to a packed crowd of folk- and world-music fans at the annual FreshGrass Festival in North Adams, Massachusetts, 10 shows into their latest global, 60-show tour. Framed by the green ridges of the Berkshires showing the first flashes of fall colors, the scene could not have been farther from the band’s desert homes. Afterward, Alhousseyni reflects on the band’s achievements. “From the beginning,” he says, “our idea was to create a new style. That was the objective of Tinariwen and of Tuareg rebellion, the same goal, the same feeling: to create something new for the people of the Sahara.”

From the beginning, the guitar-based sounds offered a popular alternative to the traditional music of Tuareg griots, hereditary musicians whose song repertoire focused on past glories to the accompaniment of a spike lute called a tahardent.

“The history of the Tuareg in the desert needed to be revived,” says Alhousseyni. “But you can’t revive it in the way it was sung in the past. You have to use an instrument that people did not know before. But you also have to let them find a logic that they know within the sound. This group had to be something modern, not traditional. Because with the traditional system, it’s difficult to wake people up.”

Little did these musicians imagine that their wakeup call would reach so far and wide. It was in the early 2000s that the term “desert blues” began to circulate, and it works in the sense that the melismatic singing and minor pentatonic scales of Tinariwen are elements shared by American blues with clear roots in Islamic West Africa. But there is particularity in the emotional heart of Tuareg blues: asuf, it is called, a sound that translates—imperfectly—as profound melancholy. “Exile, suffering, separation from relatives,” said Alhousseyni. “Our music was created in some of the same conditions as the blues.”

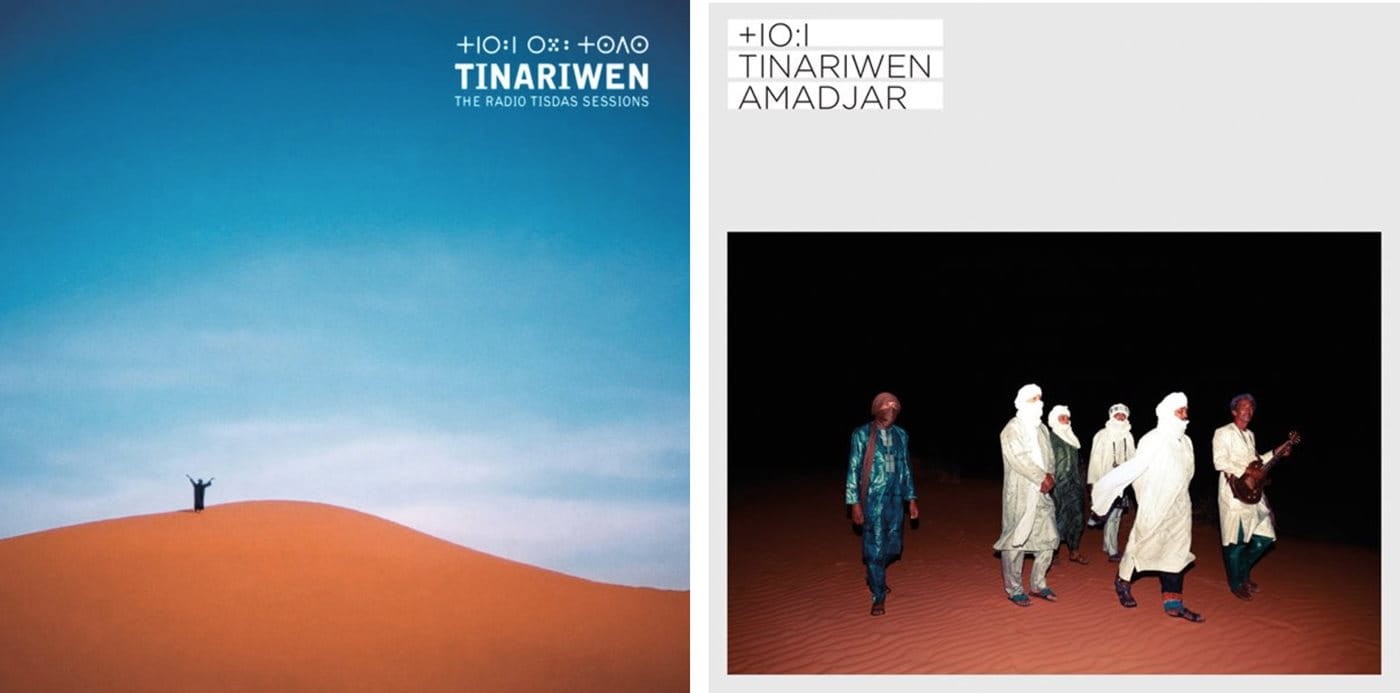

After a peace negotiated in the north of Mali became official in 1995, Tinariwen’s music began to circulate more widely. One of the people whose ears it reached was British guitarist and producer Justin Adams. In 2000 he met up with Tinariwen in Kidal, in eastern Mali, where together they recorded an album they called The Radio Tisdas Sessions, after the radio station they used as a studio.

“Their music had been banned [in Mali] during the war,” recalled Adams in a 2004 interview. “I think you could spend three months in prison for possession of a cassette. It seemed like everybody in the whole of Kidal knew Tinariwen’s songs. When they did a concert in town, it didn’t really matter who was doing backing vocals. Anybody could just get up from the audience and get on the mic and join in the choruses.”

Released in 2001, the album proved catnip for the fast-growing world-music industry. Tinariwen’s rough authenticity, beguilingly relaxed guitar lines and loping rhythms were perfect complements to the more highly produced African sounds emerging from studios in Paris, London and elsewhere. Tinariwen was in demand before it ever mounted a tour.

Today, seven albums later and with a 2011 Grammy Award, buoyed by sustained global fame, Tinariwen seems unchanged in its essentials. The 2019 tour, in support of its new album, Amadjar, featured just six musicians, including both early members Alhabib, Alhousseyni and Hassan Ag Touhami together with three younger players. All of them, along with the 14 or so other non-touring band members, still live in various parts of Mali and Algeria. They come together in various groupings two or three times a year to tour, but the foundational blends of hypnotically coiling, guitar-driven grooves and mournful, asuf-inspired melodies that address toils and aspirations of the Tuareg peoples—always sung in Tamasheq—remain constants.

The word amadjar means “stranger,” and for Alhousseyni, it is an idea that takes him back to his childhood. “Nomadic people,” he says, “must welcome strangers a lot. So they keep aside a cache of food that they don’t eat for the time when a stranger comes. We children were always happy when we saw a stranger come and stay overnight in our encampment because we knew there would be extra food that night.”

The album began after Taragalte Festival 2018, an annual gathering of world musicians in the Moroccan desert. From there, the Tinariwen musicians moved south to Mauritania, where they met up with famed griot vocalist Noura Mint Seymali and her guitarist husband Jeich Ould Chigaly. Over 15 days they recorded basic tracks in the desert, later overdubbing contributions from Western artists, including mandolin from Micah Nelson (Willie’s son) and violin from Warren Ellis of The Bad Seeds.

This, Alhousseyni explains, is part of their global outreach, but guests must find themselves within the band’s sound, not the other way around. “We don’t tell them anything. I’ve never told a musician, ‘Do this, do that,’” says Alhousseyni. “We created the style of music, so it’s natural that we defend it. Even if we bring other elements into it, we keep the structure, the basis, the same.”

In lyrics, too, Tinariwen remains committed to common Tuareg aspirations. The new album features Alhabib merging his guttural baritone moans with soaring, nimble vocals from Seymali, together longing for unity and freedom and “return to our homeland.” Alhousseyni points out that Amadjar is really a collection of songs that date from as far back as 25 years ago, “but it’s as if they were written in advance. The problems that they spoke about are the same problems that still exist in the north of Mali. It is really not necessary to create new songs.”

Andy Morgan, a writer and onetime Tinariwen manager, once observed that many of Tinariwen’s songs begin with “imidiwan,” a greeting that means “my friends.”

“They are talking to their circle, to people like them,” he says. The implications follow: “‘My friends, wake up, be aware. We’re erring in the desert. We’re thirsty. What is our future? Where are we going?’” Among the most persistent themes in Tinariwen’s songs is the call for unity, not only between Arabs and Berbers, but especially among Tuareg clans and factions.

“The Tamasheq [-speaking peoples] are too small to be divided,” laments Alhousseyni, adding that those who understand this are, like the Tuareg themselves, a minority. “When you want to do something good,” he adds, “you are always in a minority. But you have to know that one person who has the will to do something good is equal to 20 who want to do something bad.”

About the Author

Banning Eyre

Banning Eyre is senior producer for Public Radio International’s Peabody Award-winning Afropop Worldwide (afropop.org) and author of a number of books on African music and history.

Charlotte Doughty

Charlotte Doughty is a student majoring in journalism and Latin American studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

You may also be interested in...

Moroccan Musician's Mission: Revive Overlooked Folk Traditions

Arts

For more than 10 years, Moroccan native and New York resident Hatim Belyamani has focused his non-profit Remix⟷Culture on offering digital sample and remix tools that give exposure and preserve access for traditional acoustic music around the world.

Albania Folk Music Performers Seek to Preserve Tradition

Arts

For centuries iso-polyphony, a style of folk singing, has chronicled Albanian life. The songs are part of a rich tradition, vital to weddings, funerals, harvests, festivals and other social events. Indeed, a Ministry of Culture official dubs it “the autobiography of a nation,” a means for the preservation and transmission of different stories. Recently, crowds gathered for the National Folklore Festival in the “stone city” of Gjirokastër, demonstrating that interest in iso-polyphony remains high. The challenge is getting younger generations to engage. But some are taking up the call.

Lute and Lyres' Legacy: Echoes in The Oud Instrument and Beyond

Arts

History

For more than 4,000 years. people have adopted, adapted and adjusted the lute, resulting in its countless variations. Along the way. some innovations have proved both consequential and simple.