Shanidar Cave Yields New Signs of Neanderthal Emotions

Traces of flowers in a Neanderthal grave found 45 years ago in northern Iraq led to a theory that even the earliest humans may have expressed emotions in ritual. In 2016 archeologists returned: Could new finds lend support to the theory, or not?

With the findings of flowers in association with [a gravesite of] Neanderthals, we are brought suddenly to the realization that the universality of mankind and the love of beauty go beyond the boundary of our own species.

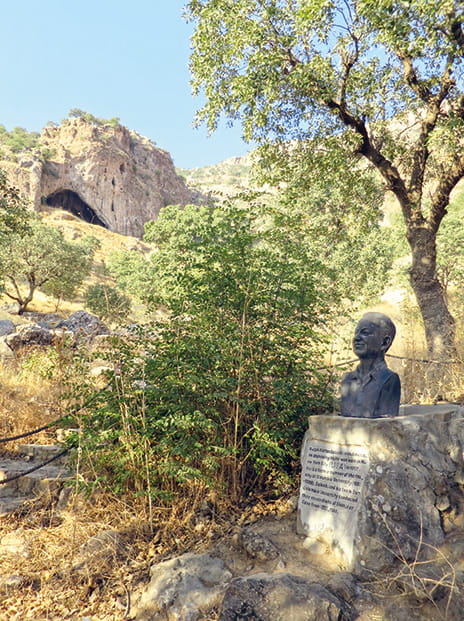

—Ralph Solecki, Shanidar: the First Flower People, 1971

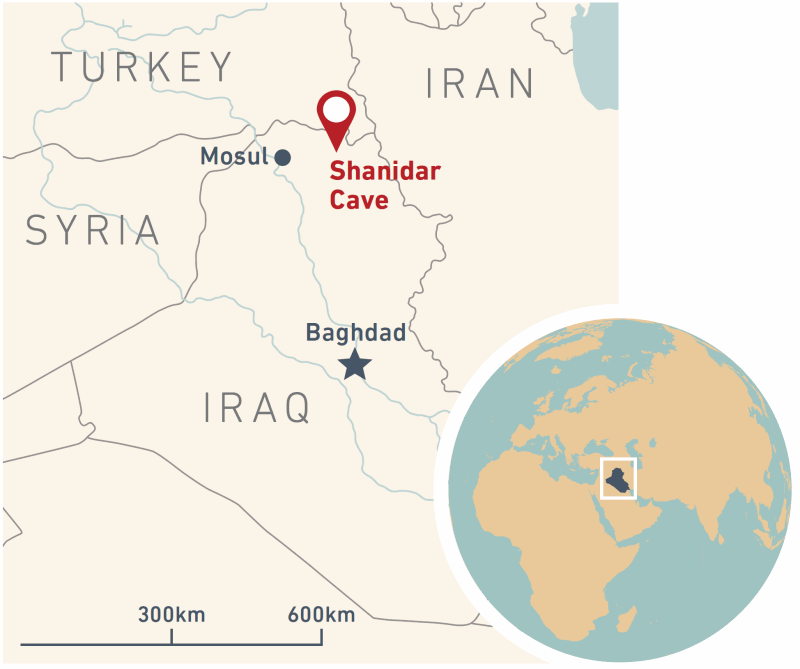

Forty-five years after archeologist Ralph Solecki wrote those words, “it was in late spring and abominably hot,” recalls archeologist Graeme Barker of the 2016 excavation season at Shanidar Cave, 100 kilometers northeast of Mosul in the foothills of the Baradost Mountains in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq. The surrounding foothills were dry and dusty because shepherds had grazed their flocks especially heavily that year. Barker, who was 69 at the time and is Emeritus Disney Professor of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge, explains that this reduced the grass and flower samples he and his team hoped might help settle one of the most intriguing questions about our closest evolutionary relatives: Did Neanderthals think and feel like we do?

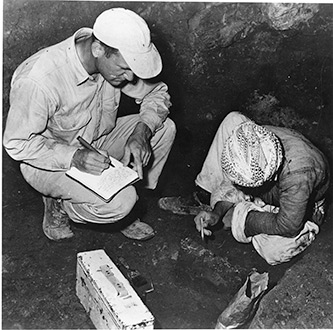

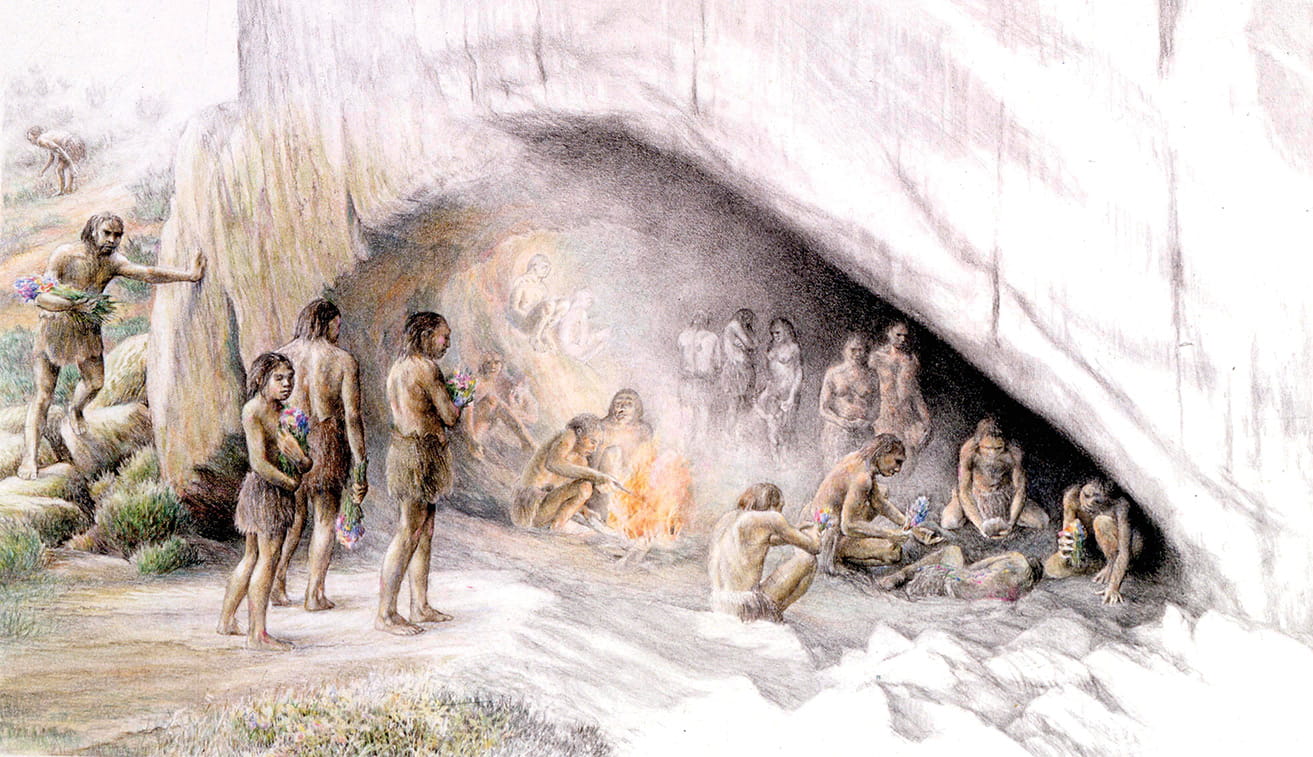

The question goes back to the late 1950s, when archeologist Ralph Solecki of Columbia University excavated at Shanidar the remains of 10 Neanderthal men, women and children who had lived an estimated 60,000 years ago. Particularly compelling were remains found with significant quantities of pollen from those brightly colored flowers that would prove scarce to Barker. Solecki’s team named the remains Shanidar 4. The pollen analysis showed traces of hyacinth, bachelor’s button and hollyhock, all hypothesized to have been woven into the branches of a pine-like shrub and placed with the body. The discovery led Solecki to introduce the theory that if Neanderthals could express lamentation of death, then perhaps they were capable of far more too. The act of grieving or paying respect to the dead, as well as the participation in some type of death memorial ritual, suggested to Solecki that Neanderthals possessed compassion.

This took the first swing in what has become a steady tearing down of the brutish “caveman” stereotype that had been dominant over the century since homo neaderthalensis was first classified scientifically in 1856. Evidence continues to support understanding that Neanderthal populations inhabited southern Europe and western and south-central Asia from roughly 400,000 to 40,000 years ago, and that they overlapped with early homo sapiens—us. The “bad press” for Neanderthals, as Barker calls it, persisted until Solecki’s excavation. If Neanderthals possessed compassion enough to arrange and place flowers in the grave, then did they also possess other complex abilities, such as learning, communication, awareness, ritual and even belief systems?

Solecki found further evidence for this in another male skeleton that they named Shanidar I. Forensics indicated Shanidar I not only lived a long life for his time—around 40 years—but also survived a traumatic head injury at some earlier age as well as perhaps other physical injuries as a child that likely incapacitated him to some degree. Solecki noted the healed wounds of Shanidar I suggested that Neanderthals may have cared for their sick or disabled.

However, Solecki’s interpretation of the pollens was contested, due to what critics called insufficient safeguards against contamination as well as Solecki’s lack of comparison samples from surrounding deposits. As intriguing as it was, it could not be regarded as proof. Yet the implications were profound and tantalizing enough to trigger a decades-long avalanche of research in archeology and anthropology. Barker is but one of many spurred on by Solecki, aided now by sophisticated new techniques like DNA analysis.

In 2011 the Kurdistan Regional Government invited Barker to come to Shanidar and reexamine Solecki’s findings. It is the first such invitation issued since 1960.

“I could hardly believe it,” Barker says, remembering the excitement. (Barker later notes that Solecki, long retired, had been “enormously supportive.” Solecki passed away in 2019.)

Five years later, in 2016, Barker led a team of specialists to reopen Solecki’s 14-meter-deep trench and examine the soils using advanced techniques of micromorphology and more.

“What we were hoping was simply to expose the different locations where Solecki found the Neanderthals, date them and get information about climate and how they were living using methods not available to him,” Barker says. “So we’d end up with a good chronology of when they were there and how they were behaving.”

They found more than they expected.

“As we got down into the intact stratified deposits, we found some clearly articulated limb bones,” he says, explaining how they gingerly used trowels and brushes to expose the bones of the body they named Shanidar Z. It soon became clear this was, like Shanidar 4, likely an intentional Neanderthal burial. The body had been placed on its back with its head and shoulders raised on a triangular stone. The head was turned slightly to its left and set to rest on the closed left hand as if in a dreamy sleep.

“The hand and the stone look as if they were placed there,” says Barker. “It’s not one of the stones from the sort of rockfall that’s below and around and above.”

Barker also notes the micromorphology sections “clearly show that the body is in a location that has been partly changed by people. It is in some kind of scoop that is suggestive of an intentional burial.”

The micromorphology slides also showed evidence of pollen. How it came to be there and whether it is pollen of flowers or other vegetation is not yet conclusive, he says, but “the cumulative evidence is looking more and more like the undeniable evidence for a deliberate burial associated with ritual behavior.”

This is significant because it shifts our understanding of the grave closer to an example of what archeologists call “mortuary behavior.” This takes place when people do not merely bury a body but perform rituals around it—like nearly all modern cultures do today.

As significant as they may turn out to be, Barker’s findings are far from isolated. Among the research that Solecki’s hypotheses helped launch, four stand out, and all have added supporting evidence.

Neanderthals “clearly used plants such as chamomile, yarrow and others for flavor and for medication.”

—Robert Power

Neanderthals prepared some foods.

Robert Power, a research associate at Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich focuses on diet of hunter-gatherer and early farming societies. He analyzed the residue and calculus on the teeth of Neanderthals. In addition to being predominantly carnivorous, “they clearly used plants such as chamomile, yarrow and others for flavor and for medication,” he says. And it wasn’t always just “gathering” either: They enjoyed foods such as olives, he says, that required processing to be palatable.

Neanderthals embraced technology.

And it was more than spears and stone axes, says Bruce Hardy, professor of anthropology at Kenyon College, who studies Neanderthals and human ecology. Since 2006 he has been excavating Neanderthal occupation levels at the Abri du Maras site in a valley near the Ardeche River in France. The site is rich in stone tools, and some show, under a microscope, tiny fibers stuck to them. Though it was originally unclear at first what the fibers had been, one day Hardy noticed that attached to one of the items was something larger: distinct bundles of fibers in three-ply cord about 6 millimeters long. It dated to between 41,000 and 52,000 years ago.

Cheers broke out in the lab, Hardy recalls of the moment of discovery.

“When I found this piece with all those twists, we knew we were really on to something, because cordage is not as simple as it looks,” he says. “It takes a good bit of imagination and mathematical understanding.”

Bast, or layers of inner tree bark, likely from conifers, are fibers that are first S-twisted to form yarn, he explains. Then the yarns are Z-twisted in the opposite direction, which prevents unravelling, to form a strand or cord. Hardy explains that as the multiple cords are twisted to form a rope, and the ropes interlaced to form knots, the methods suggest broader technologies: bags, mats, nets, fabric, baskets, structures, snares and even watercraft.

“There’s no reason to think Neanderthals are cognitively any different than we are,” says Hardy. Because the Abri du Maras cord was a rare perishable material, “if we look more carefully—in particular, microscopically—in the sediments and on tools we are going to find they were doing more.”

Neanderthals made art.

Paul Pettitt, professor of archeology at Durham University in the UK, specializes in paleolithic art. In 2015 he took a team to three cave sites in Spain to analyze samples of more than 1,000 red-and-black paintings and engravings on the walls. He noted the differences in craft techniques and tools, including hand stencils and handprints, geometric shapes as well as figurative representations of horses, deer, birds and more. He took particular note of three images: a red linear motif in La Pasiega in northern Spain, a stencil of a hand in Maltravieso in west-central Spain, and red-painted stalactites and stalagmites in the Cave of Ardales in southern Spain.

Pettitt and his team dated the art to more than 64,000 years, which predates the arrival of modern humans in Europe by at least 20,000 years. The inescapable implication is that the artists must have been Neanderthals.

Others, however, have challenged Pettitt’s use of standard Uranium-Thorium (U-Th) dating and maintained the necessity of using other methods too. But Pettitt stands by his results. “We actually sample in the paint itself, and when we have exposed the pigment underneath, we stop.”

“It’s not surprising they would create the first hand stencils or the rectangle of overlapping finger dots,” Pettitt says. “They wanted to leave a mark of their body on the external landscape.”

The idea that Neanderthals likely were able to sketch on walls further contributes to understanding their cognitive abilities.

“The overwhelming majority of cave art remains undated,” Pettitt says.

Neanderthals could be attractive.

One of the perennial questions about Neanderthal behavior is whether they interbred with modern humans, seeing as the two species shared large swaths of territory, including the region around Shanidar, for more than 10,000 years. It is also the one major question science has largely settled.

“What the earliest claims were for interbreeding is a lot of people had thought it possible, if not probable,” says Greger Larson, director of palaeogenomics and bioarcheology research at Oxford University’s School of Archaeology.

Larson notes when the first Neanderthal genome was published in 1997, it showed non-African populations with Neanderthal DNA mixed together.

“Then as more Neanderthal DNA was reported, it showed that admixture was pretty common,” he says, noting in people today the amount varies from less than one percent to more than two percent depending on heritage.

“Neanderthals and humans are so closely related they are as similar as wolves and coyotes ... and we know that those species can readily hybridize.”

—Greger Larson

“Neanderthals and humans are so closely related they are as similar as wolves and coyotes,” he says. “And we know that those species can readily hybridize.”

From his work in France, Hardy has also theorized on interbreeding.

“To think of something as closely related to us as Neanderthals are, to think that they don’t have symbolic thought when ultimately we are seeing through DNA evidence that they are interbreeding with modern humans’ ancestors—it doesn’t make any sense,” Hardy says. “Why are we going to interbreed with something incapable of symbolic thought?”

Hardy reckons the shared DNA and evidence of interbreeding suggest something further.

“At some level we’re not really talking about an extinction,” he says. “We’re talking about an assimilation, where part of the Neanderthal genome is brought into the modern human.”

Or as Larson puts it, if Neanderthals were alive today, they could blend in aboard a bus in any city, particularly in Europe or West Asia.

The discoveries at Shanidar Cave and elsewhere add that not only would the Neanderthals blend in, but any one of them might give up a seat for a less able passenger. Or hold the door.

Barker hopes Shanidar Cave will continue to reveal more answers. Every scrape of the trowel, every swish of the brush, every microscopic soil analysis promises clues to come.

You may also be interested in...

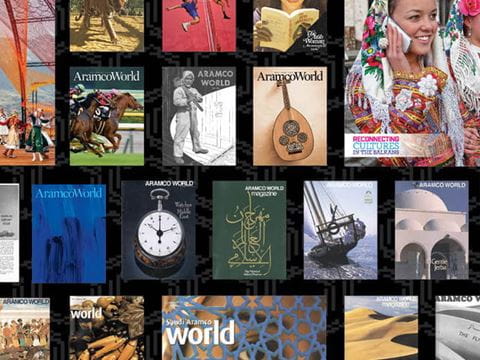

AramcoWorld: 75 Years of Cultural Connections

Arts

History

Since its origins in 1949 as a company newsletter for Aramco, AramcoWorld has evolved to focus on global cultural bridge-building across the Arab and Muslim world and beyond.

AramcoWorld Explores Universal Food and Cross-Cultural Identity

Food

History

Voices That Shape Cross-Cultural Understanding

History

In its 75-year history, AramcoWorld has enlightened readers with stories about people throughout history and the modern world who have made an impact. Part 5 of our anniversary series examines the magazine’s positive portrayals of explorers, teachers, scientists and others to fulfill a mission of cultural bridge-building.