A Conversation With Art Collector Book Editors Peyton and Paul

In Arts of South Asia: Cultures of Collecting, coeditors Allysa B. Peyton and Katherine Ann Paul draw us into the personal, institutional and political dynamics surrounding objects that have journeyed from South Asia India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Bhutan to museums abroad and, in one case, undergone repatriation.

In Arts of South Asia: Cultures of Collecting, coeditors Allysa B. Peyton and Katherine Ann Paul draw us into the personal, institutional and political dynamics surrounding objects that have journeyed from South Asia India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Bhutan to museums abroad and, in one case, undergone repatriation. We learn how individuals and some of the many women donors of Newark Museum in New Jersey acquired works; how collectors and curators interpreted and exhibited them; and how, in a few instances, institutions returned them to their country of origin. We also meet a lively mix of collectors, from towering figures like Ananda Coomaraswamy and Chester Beatty to British civil servants and American missionaries. Whether works are carved doors, Mughal paintings, bidriware from South Central India or statuary from Hindu temples, their stories address universal questions of representation and ownership. And the timespan of these case studies from the early 1800s to the 2010s-highlights the changes in attitudes and values. Peyton and Paul, recently sat down with AramcoWorld to explain more about their book and why they chose to lean in on South Asia.

Tell me why you both chose to examine collectors of South Asian art?

Peyton: We refer to the imprint individual collectors have on our institutions.

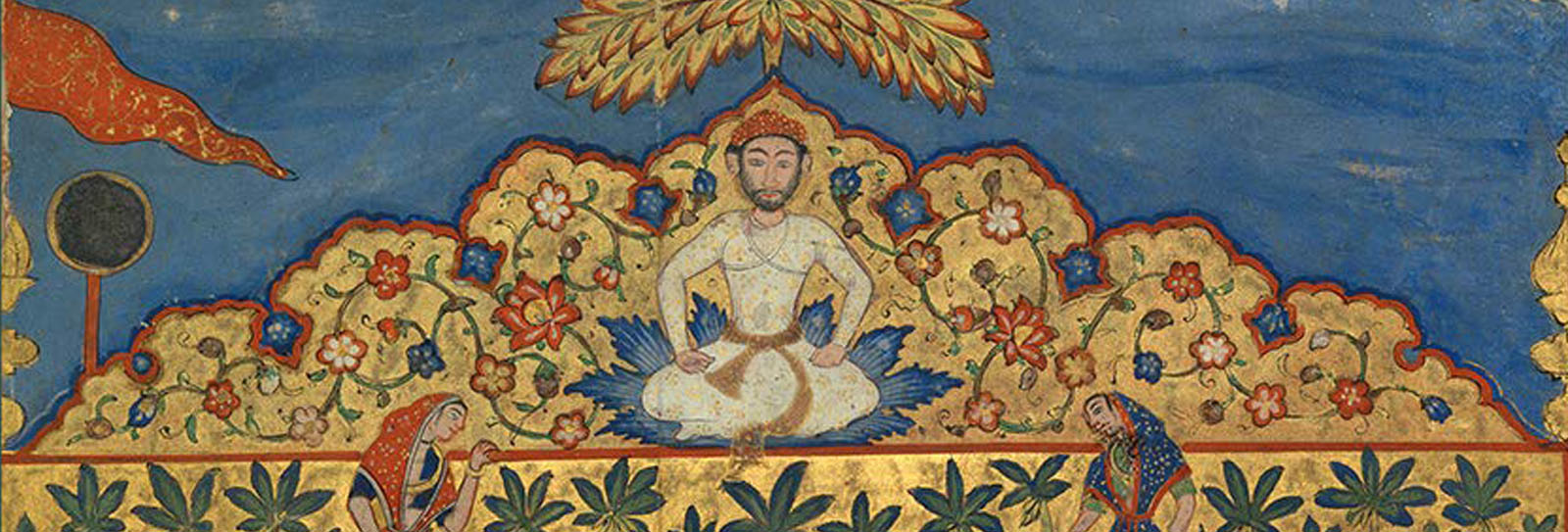

Paul: In Hyder Abbas's essay, for example, Chester Beatty is negotiating with British Museum and V&A curators, essentially divvying up certain "great works" and developing canon that prized Mughal painting over other kinds of painting from South Asia.

Peyton: There's Hugh Nevill in Shushma Jansary's essay: He's a botanist, an insect-lover, and he's collecting everything! So, the Nevill Collection at the British Museum has things formerly termed folk art. They were marginalized but now, for the first time, they've been properly photographed and published.

Paul: There's a feedback loop that once you create an authoritative volume, its images become the masterworks. That's why we were so careful to include images that were not just ones people were used to seeing. We wanted to add to. not underscore, existing masterpiece narratives.

Was Mughal painting popular with early collectors? Why is that significant?

Paul: With palm-leaf manuscripts, you had to wrap your head around their being long and not bound-but illustrated Shahnamahs or Hamzanamas were akin to medieval manuscripts. Even seeing Arabic on the page was familiar from the Nasrids in Spain.

Peyton: Mughal painting had imperial patronage, too. You have studios bringing in regional artists who learn from each other. I think that, too, helped set the taste standard for several centuries.

Paul: The fact that Mughal paintings occur in a number of the book's essays demonstrates how they're woven into a greater tapestry of South Asian arts-it is useful to recognize this in these times of polarization globally.

How is recent scholarship shaping exhibition strategies?

Paul: Music and dance are inextricable from, say, a carving in the South Asian context, and in the diaspora the gathering is valued so much more than having beautiful items in a gallery, inactivated. So, Gauri Krishnan's essay talks about bringing in intangible cultural environments. That's the direction in which things have to continue to go.

What does that mean for Islamic art?

Peyton: Bringing in poetry, music, dance, video, maybe smells—

Paul: —the alliteration and cadence of Farsi poetry or excerpts from the Qur'an to provide an aural addition. I've now seen where they will have the call to prayer from five different locales, so you can hear regional differentiations.

Peyton: We need more of these connections between academia and museum practice. And it works out really well because it's a lot more fun and interactive, and it can bring in a range of visitors.

You may also be interested in...

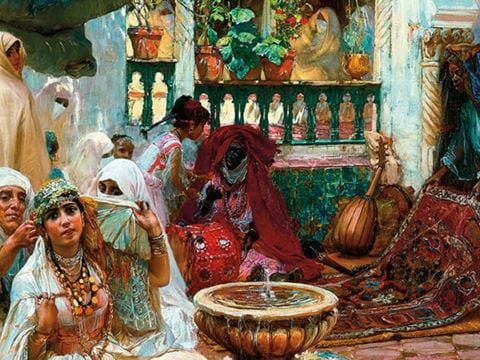

How Mohamed Shafik Gabr Redefines Orientalism

Arts

In 1884, a 23-year-old painter named Étienne Dinet took a break from Paris to travel to Algeria, where he became a prominent Orientalist artist—a European depicting scenes of cultures not his own. In the 1990s, art collector Shafik Gabr noticed that Dinet stood out among a number of Orientalists whom Gabr says approached their work as an “art of face-to-face engagement between East and West.” Gabr credits Dinet and other “respectful observers” with the inspiration to inaugurate East-West: The Art of Dialogue, an annual intercultural encounter program for emerging leaders.

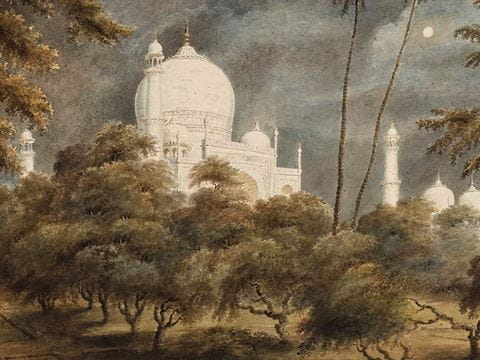

How Historical Paintings of Taj Mahal Changed Perceptions of India

Arts

History

The depiction of the Taj Mahal in the works of Indian and British artists in the 1800s helped bolster enthusiasm for the country & rsquo;s rich culture, architecture and society. One such painting, & ldquo; The Taj Mahal by moonlight,& rdquo; stirred a bidding frenzy at a recent auction, and some experts argue that such paintings have helped change perceptions of India in the West.

How Maliha Abidi Paints Stories of Pakistani Women's Strength

Arts

After growing up in Karachi, Pakistan, and moving to California as a teenager, artist and author Maliha Abidi found it difficult to find stories of women who looked like her or with whom she felt she could identify.