Sami Katafi and The Legacy of 'Mi Amigo Angel'

By tackling often overlooked societal issues, Palestinian-born Sami Kafati’s body of work has shaped Honduran cinema even years after his passing.

“Sami Kafati has been my most important teacher,” says Honduran filmmaker Darwin Yaney Mendoza. “I still learn from him every day. We are in conversation in so many ways.”

Mendoza has never actually met Honduras’ first filmmaker, who died in 1996, years before Mendoza began making his own films. But the ghost of Kafati, who was born in Palestine, is present in Mendoza’s aspirations—and throughout the story of Honduran cinema.

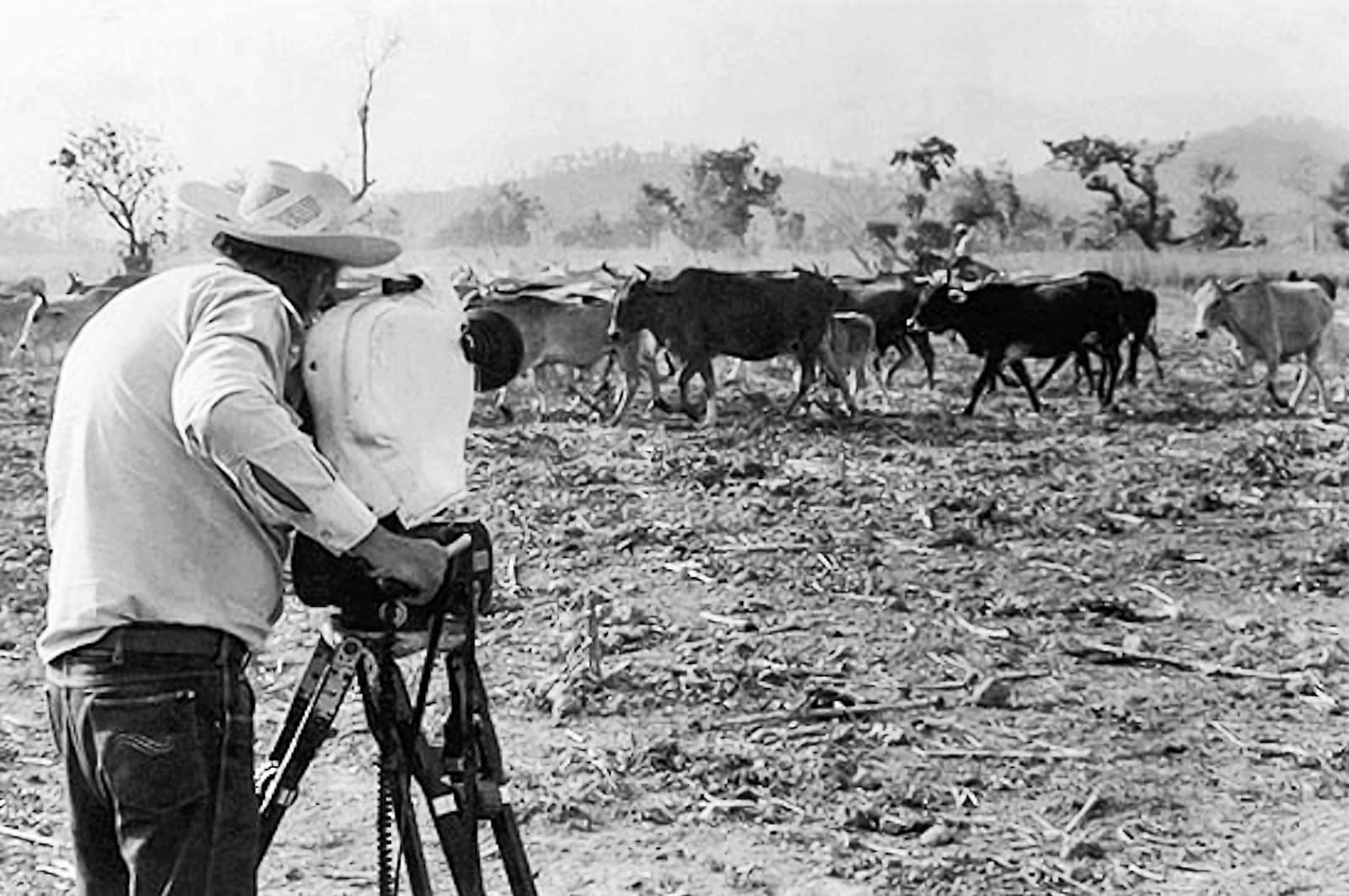

Kafati’s body of work includes many Honduran firsts. His masterpiece, No hay tierra sin dueño (There Is No Land Without an Owner), is considered Honduras’ first feature film. It is the only Honduran film to have had significant play outside Latin America, debuting at the Cannes Director’s Fortnight. But copies have deteriorated—which is why it also is the first film a new archive has chosen to restore. Saving it for future generations.

No hay tierra sin dueño centers around a ruthless rancher, Don Calixto, who kills or otherwise destroys anyone who questions his authority over the land. The film took 22 years to make, and eventually released posthumously. It tackles often unspoken issues, including agricultural practices (Honduras’ most important industry), class, race, religion and gender. “When it was released in the cinema here in 2003, it played for two weeks, and I kept coming back to watch it every day,” recalls Mendoza, who has seen the film some 75 times. “It was in black and white and set in the 1980s, but it was very relevant to the time, and it is still about us today. Every time, I still discover something new. I have understood since I first saw it that Sami was a grandmaster of cinema—and of Honduran society.”

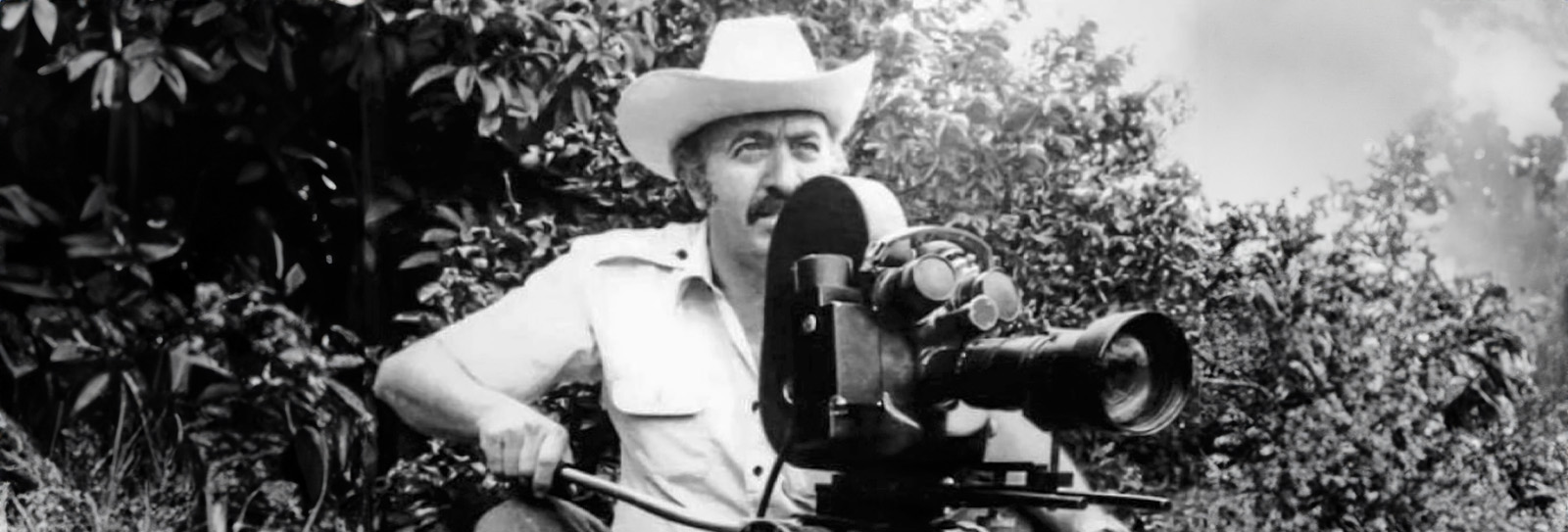

At Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras (UNAH), in the capital city of Tegucigalpa, Mendoza co-founded Honduras’ first film program. The campus is also home to the new Cinemateca Enrique Ponce Garay, the film archive that safeguards Kafati’s surviving work. A poster of Kafati behind the camera is the first thing one sees upon climbing the three flights to the cinemateca. That poster is also the cover of the first book the cinemateca has published, a collection of essays about Kafati in 2018. The cinemateca’s founder is Rene Pauck, a jovial French documentary filmmaker who was Kafati’s friend. He and cinemateca manager Luis Griffin are overseeing the restoration, which could take years. In the meantime, they excitedly share other work from Kafati, including rare documentary footage he shot in Managua, Nicaragua, after the 1972 earthquake that nearly wiped out the city. “Sami was drawn to those suffering,” says Pauck.

The subjects of the cinemateca’s next two books are Honduras’ other two film pioneers, Jorge Asfura and Fosi Bendek. The two share one more thing with Kafati: They, too, are of Palestinian descent. Arab Hondurans comprise less than 2 percent of the population, but most Hondurans know their family names because of their pioneering success in business.

“Asfura opened the first film lab in Honduras in the 1940s,” says Griffin. “The Asfura family was also hired by the government and private companies to make documentaries and commercials—or they filmed just because they liked to. So, they have provided a very important historical memory for Honduras.”

Bendek was one of Kafati’s closest friends. Beloved in local lore, Bendek often hosted screenings at his ice-cream shop, sometimes delighting attendees with his footage of the neighborhood, including people in the audience. He directed El reyecito (The Little King), shot by Kafati in 1979. As a soliloquy, the film addresses the wrongs and hardships of the world, including in Palestine.

Kafati’s work focused on Honduras—with subtle odes to his heritage and hope that the “turcos,” a derogatory name for Arabs, be seen as part of Honduran society. Midway through No hay tierra sin dueño, Don Calixto visits a general-store owner, the Arab stereotype, played by Bendek. In a comedic Arab accent, Bendek’s character shares news of his wayward adult children and then cradles the belly of his new Honduran wife, saying, “This is the future.” It is a touching scene, a rare light moment in the film.

“This was Sami’s way of showing his wish to merge his two identities, Palestinian and Honduran, as one,” says Katia Lara, a Honduran filmmaker whose first documentary, Corazon Abierto (Open Heart), made in 2005, was about the making of No hay tierra sin dueño. “My conscious interest in Honduran cinema began while I was studying film in Buenos Aires [Argentina]. The first name that came up was, of course, that of Sami. I felt proud but also sad I would not meet him. But he came back from death transformed into energy, impulse, spirit—whatever you want to call it—to see the film completed.”

Indeed, No hay tierra sin dueño was released in 2003, seven years after Kafati passed away. The saga of the making of the film, which he began writing in the mid-1980s, is as dramatic as the film itself. There are many milestones on the way to that story, starting with his first 10 years in Palestine.

Soon after Kafati was born in 1936, his father, Jacob, set out for Honduras to seek work “At the beginning of the 20th century, there were less than a million people in Honduras. The government welcomed immigrants, promising them good futures, because there was a labor demand,” says Jorge Amaya, professor of Iberia American history at UNAH and author of Palestinians and Arabs of Honduras. “Arabs were particularly welcome, as they had a reputation for being hard workers. Today we are 10 million people, about 175,000 of whom are of Palestinian descent.”

But before Jacob reached Honduras, World War II started, and he got stuck in Italy until immigration resumed. His wife, Maria, stayed in Palestine with her two toddler sons, the elder of whom was Sami. During that time, rheumatic fever damaged Sami’s heart. This would shape the course of his life.

“Today we are 10 million people, about 175,000 of whom are of Palestinian descent.”

— Jorge Amaya

Parts of the Kafati clan, like other Palestinian families, grew wealthy in Honduras. A branch of the Kafati family owns the upscale café chain Espresso Americano, with franchises across Honduras, Costa Rica and Guatemala, and, most famously: They own Café el Indio. “We all grew up drinking Café el Indio. This brand of coffee is consumed in every house in Honduras,” says Amaya.

But not all Kafatis had such financial cachet. “My father used to say my grandfather was irresponsible,” Samia Kafati, Sami’s daughter, says with a smile. “His favorite business was a musical-instrument store…And he used to lend money to anyone who asked. He didn’t care about saving.”

Jacob for a time also owned two cinemas. “My father and his brother would go from one cinema to the other on their bikes, delivering reels and watching films,” says Samia. “My grandfather later gave my father a camera, and that’s when he started filming. Before he passed away, when my father was a teenager, my grandfather gave him a projector.” Samia still has the projector, the rare piece of equipment the family did not have to sell for financial reasons when Kafati died. “My grandmother did not want her son to become a filmmaker because she did not see how he would make money.”

Eight of Kafati’s siblings were born in Honduras, many of them providing the music for his films, but all would heed their mother and study engineering and chemistry, among other things, while Kafati pursued his dream.

“He was like a bohemian when he was young…he used to smoke a lot,” says Samia. “His health deteriorated quickly. The relatives who owned Café el Indio helped my grandmother to take him to Philadelphia, where he a received a mitral valve transplant. It was a successful surgery, and he became very disciplined after that. Like an American.”

“No one understood taking such a dark look at the plight of children in our country.”

— Roberto Bude

Kafati, then 23, started to make money producing commercials and documentaries for hire. He used his earnings to buy equipment that couldn’t be found in the country, most notably a Moviola, the world’s first movie-editing machine. In 1964, he completed Honduras’ first narrative film, Mi Amigo Ángel. The 32-minute black-and-white film follows a 10-year-old shoeshine boy, Ángel, as he searches for his alcoholic father and witnesses a violent attack on his mother. Shot in downtown Tegucigalpa, it opens with the first-ever aerial shot of the city. Ángel’s walk through the streets is also a walk through the city’s social and ethnic groups. Like all of Kafati’s films, it stars amateur actors, including his youngest brother playing Ángel’s Arab friend, and a man playing the owner of a fabric store, another stereotypical Arab business.

One afternoon last summer, Mendoza showed the film to his students as well as 15 middle school students, the age of Ángel. All were mesmerized to see their city critically observed. They marveled at what still looked the same—the busy town square, the cathedral, the bridge across the river. Also in the audience, in a Jimi Hendrix T-shirt and beaded necklaces, was Roberto Bude, a journalist and close friend of Kafati who had a small role in No hay tierra sin dueño.

“Sami asked a relative to screen Mi Amigo Ángel in one of his theaters. But no one understood taking such a dark look at the plight of children in our country,” Bude told the students.

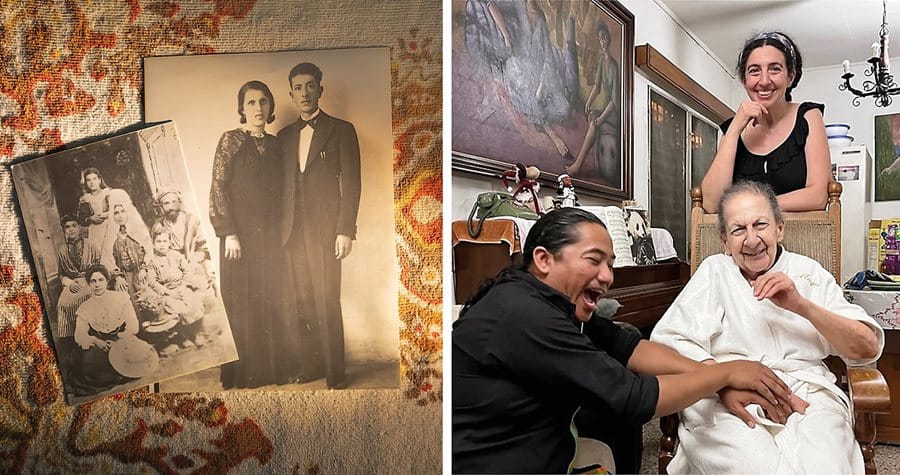

At this point, Kafati had met his future bride, Norma, whose Palestinian family owned a store. Mi Amigo Ángel was essentially Kafati’s portfolio piece to apply to Rome International Film School to formally study Italian Neorealism, the style his filmmaking already resembled. He worked at an auto-sales shop to pay for his travel—and a ring for Norma. “Her photo is the only thing he took to Rome,” says Samia.

Today, Norma and Samia still live in the house the couple moved into when they married, which Kafati mortgaged to make No hay tierra sin dueño. Kafati planted most of its small, lush garden. Missing now is his olive tree, the symbol of Palestine, not native to Honduras. “The olive tree died right after he did,” says Samia.

A kitchen refrigerator is where Kafati stored his films. The living room appears untouched from when it served as Don Calixto’s living room. The house feels like a photo museum, including a shot of Kafati filming a documentary with Pablo Neruda in Chile. Samia pointed out family memorabilia, sometimes laughing at what she came across, like a note in her mother’s handwriting: Dear teachers, I am begging you to excuse my daughter Samia Valezca Kafati for not attending class on Monday and Tuesday because her father is making a movie and she has to perform in some of the scenes.

In No hay tierra sin dueño, Samia, then 9, played a child whose suicidal father kills her after his life falls into ruins because of Don Calixto. “It was kind of traumatic,” she shrugs now. “I didn’t really know how death worked.”

Mendoza and Samia were able to coax Norma out of her room. She was drawn to knowing this writer works in film and speaks Arabic, the sound of which made her smile, though her knowledge of it is limited.

“Did my dad teach you how to use the Nagra [sound recorder]?” Samia asks.

“Oh, the Nagra, of course,” Norma nods.

“I was telling them that you used to cook for everyone on set and at production meetings,” Samia says.

Norma turns to her guests. “Oh, I miss those days. I loved cinema a lot. When Sami passed away, I wanted to keep doing that, but there was no one to support me. I’m envious of you because you’re still making films.”

“But Mom, you have never been back to a cinema. We no longer watch movies as much as we did before,” Samia says.

Norma sighs. “There is no good filmmaking now.”

Norma has refused to accept the acknowledgement many people think she deserves, “Honduras’ first female filmmaker.”

“We hear about Sami, but we don’t hear about Norma,” says Laura Bermúdez, a documentary filmmaker who in 2018 co-founded the Honduran Women’s Film Cooperative. “When I learned Norma did the sound on his films and was essentially producing, I wanted to recognize her. Everyone told me, ‘Don’t bother. She won’t allow it.’”

“We revere Sami, but it’s also important to be critical.”

— Laura Bermúdez

In all his films, Kafati taught everyone everything—acting, camera operations, lighting, set design. With No hay tierra sin dueño, everyone volunteered their time over three years of periodic filming.

“Sami even did my makeup,” recalls Marisela Bustillo, who played a woman trying to hide she has been beaten. Bustillo was a student while Kafati was preparing to shoot and met with him several times for career advice. He offered her the position of executive producer, a job she learned along the way. The acting happened because they couldn’t find any other woman willing to play such a role. “He was a perfectionist, very demanding. But he was patient. For my scene, he waited until I would naturally cry rather than have fake crying,” she says at UNAH, where she now heads the communications department. “I named my second son Ángel in honor of Sami.”

“We revere Sami, but it’s also important to be critical,” Bermudéz says. “For example, while the violence against women here is very real, it does not have to be shown so graphically.”

Kafati’s heart began to tire during shooting. He died two years after completing filming, leaving behind only a rough cut. As Lara chronicles in her documentary, his loved ones thought that was the end of No hay tierra sin dueño. Samia, who, like her brother, Ramses, is a full-time engineer—despite a passion for animation and music—says her father did not want his children to become filmmakers because it was too difficult. But two years later, coming out of their grief, Ramses, Samia and Norma decided they would finish it. They reached out to Carmen Brito, a Chilean editor and friend of Kafati. She agreed to take his film reels, but Norma and Ramses did not hear from her for two years. That is because Brito could not find the original footage in the cans.

“One night, Carmen yelled out to Sami. She said, ‘If you don’t want us to finish your work, then I leave it as is.’ The next day a miracle occurred.”

— Katia Lara

“One night, Carmen yelled out to Sami,” says Lara. “She said, ‘If you don’t want us to finish your work, then I leave it as is.’ The next day a miracle occurred.” Brito opened one of the cans called “unexposed film,” and there was the original footage. No one knows why Kafati put the footage in a can with that label, but Ramses went on to oversee the editing, rejecting any change that did not match his father’s rough cut. The rest is legend.

It’s hard to imagine how Honduran film would be defined today without Kafati. Norma has given Mendoza Kafati’s book collection, in which he wrote extensive notes. “These books are my opportunity to keep talking with Sami,” says Mendoza. “I write little notes from his notes...One day we will make a film that exceeds his work, but that hasn’t happened yet.”

About the Author

Alia Yunis

Alia Yunis, a writer and filmmaker based in Abu Dhabi, recently completed the documentary The Golden Harvest.

Meridith Kohut

Meridith Kohut is a photojournalist based in Houston, Texas, who has documented humanitarian and cultural issues in Latin America since 2007. She earned a Courage in Journalism award for her decade of work covering the region and was a finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in Feature Photography.

You may also be interested in...

New Screens in Arab Cinema

Arts

Since the 1970s, independent filmmakers have been a rare breed throughout the Arabic-speaking world. But as a rising number of film festivals and streaming platforms open, opportunities for both artistic expression and viewing experiences are growing faster than ever.

Making Lawrence of Arabia

History

Arts

In 1919 American journalist and filmmaker Lowell Thomas glamorized British Army officer Thomas Edward Lawrence first in war propaganda and then in commercial cinema. His show traveled the world and gave birth to one of the most popular modern legends of Western involvement in the Middle East.

How 'The Journey' Anime Film Brought Saudi Stories To Life

Arts

The Japanese style of animation known as anime is underpinned with narratives of community, loyalty and collective purpose. Its ubiquity feeds a growing appetite for the art form, becoming popular in the Middle East.