Egypt's Mamluk Architecture in Mosque Islamic Minbar Design

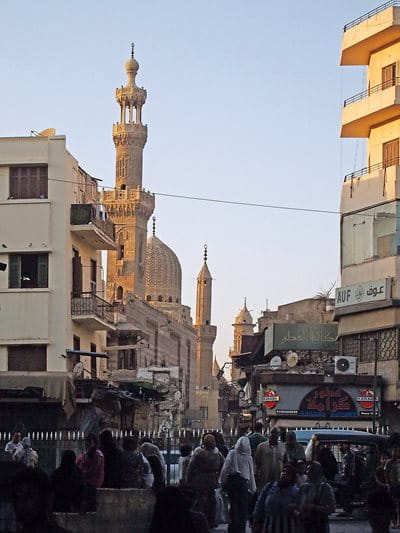

Walk into any mosque and at its front you are likely to see a stepped pulpit: the minbar. In Egypt, under the patronage of the Mamluk sultans of the 13th to 15th century, minbars became masterpieces of woodworking—most without nails or glue. Today nearly four dozen Mamluk minbars stand as a priceless but vulnerable heritage: A recent rash of thefts led to the Rescuing the Mamluk Minbars of Cairo Project, which offers protection, promotion and new opportunities for young artisans.

15 min

Written by Rebecca Anne Proctor Photographed by Richard Doughty

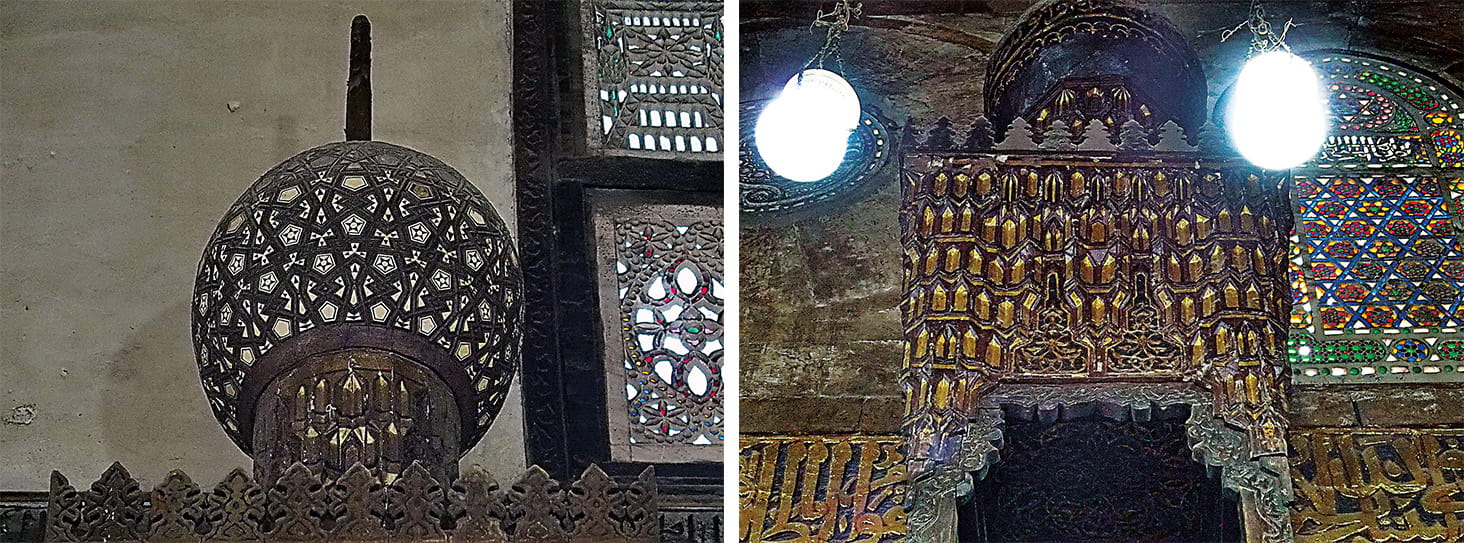

Inside the Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh Complex, the masterpiece minbar, completed in 1417 CE, was partially looted in 2006 and again in 2011, but the pieces were recovered, and the minbar has been restored.

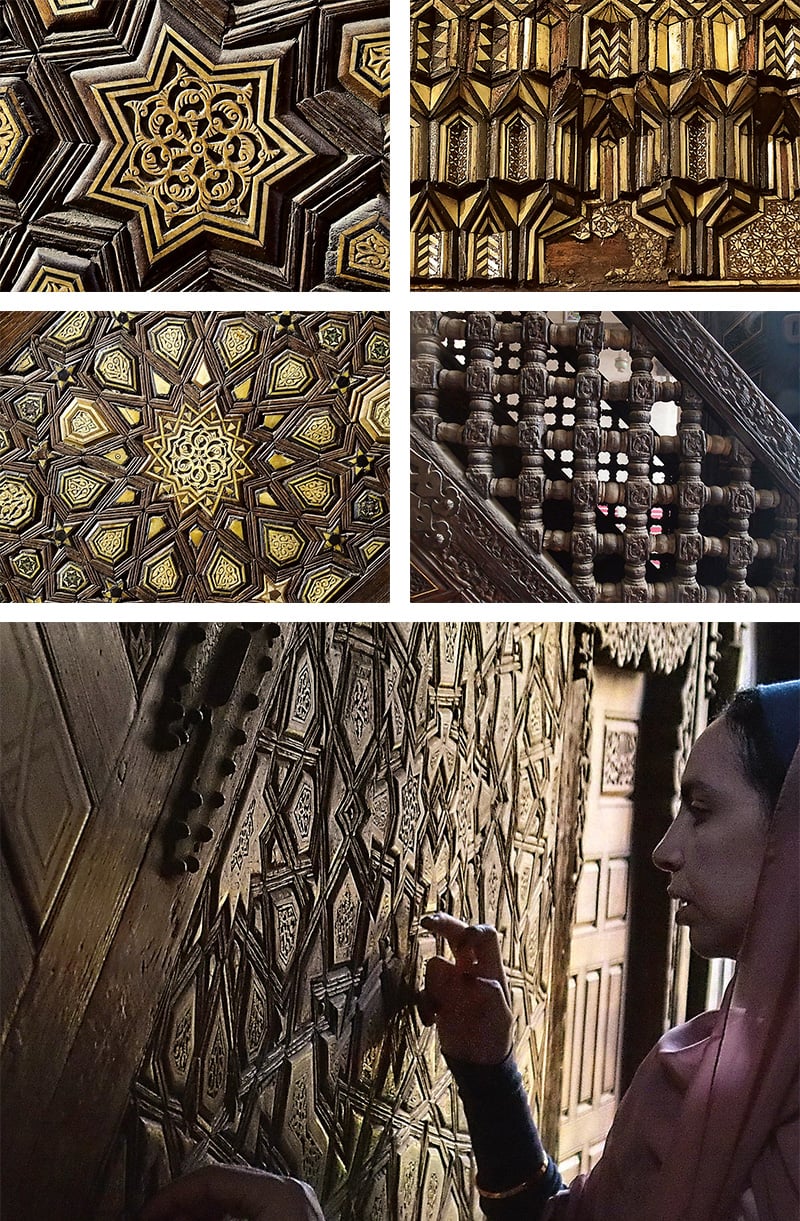

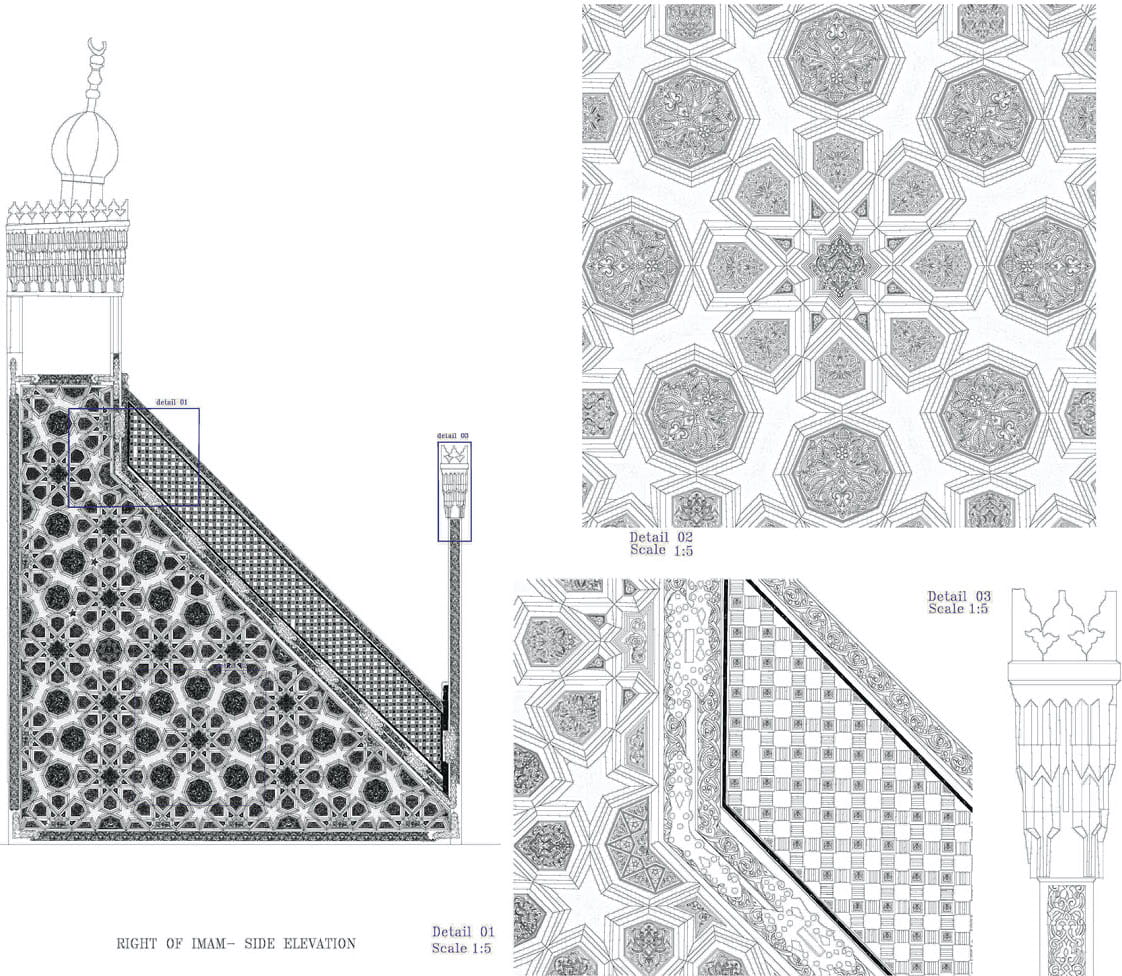

On the ground floor of his workshop in a former palace amid the narrow streets of Darb al-Ahmar, one of the oldest districts in Cairo, Hasan Abu Zayd squints as he shaves slivers from one end of a thumb-sized rectangle of wood. He continues until the joint fits snugly into the lattice of octagons, hexagons and stars that splays out across his table. Fitted among more than 1,000 other pieces, it becomes part of one of the two side panels he is reconstructing for the 15th-century minbar, or stepped pulpit, that was stripped by thieves more than a decade ago from inside the nearby Mosque of Ghanim al-Bahlawan.

Now age 70, Abu Zayd is a master woodworker descended from a woodcrafting family that goes back at least five generations. He is also one of the only remaining masters of gameya, the joinery technique that artisans used to create dazzlingly intricate wooden patterns on doors, windows, walls and, most spectacularly, on minbars during Egypt’s Mamluk period. This era lasted 267 years, from 1250 CE to 1517, and it has become known as a zenith of Egyptian Islamic arts and architecture. Sultan after sultan commissioned ever grander and more elaborate works in metal, stone, calligraphy, architecture and more. Among the resulting masterpieces, the wooden minbars are among the most elaborate of all.

In the art-collecting world, this has not gone unnoticed. Nearly every major collection of Islamic art has acquired, at one time or another, a piece of an Egyptian Mamluk minbar. Various parts of minbars can be found in London at the British Museum, and in 1867 what would become the Victoria and Albert Museum purchased a whole minbar commissioned in the late 15th century by Sultan Al-Ashraf Qaytbay, and it has been on display there ever since. Panels from the minbar of Sultan Lajin, created in 1296 for the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, are dispersed among 12 museums and three private collections.

“The skill used to carve the woodwork on these minbars is extraordinary,” says Venetia Porter, curator of Islamic and Contemporary Middle East Art at the British Museum. “These Mamluk minbars are monuments filled with history. Every time you walk into a mosque with one of the Mamluk minbars, you feel the weight of Mamluk history. Each one was commissioned by a sultan, or a patron, and they found the best people to do them. That’s why the craftsmanship on them is so extraordinary.”

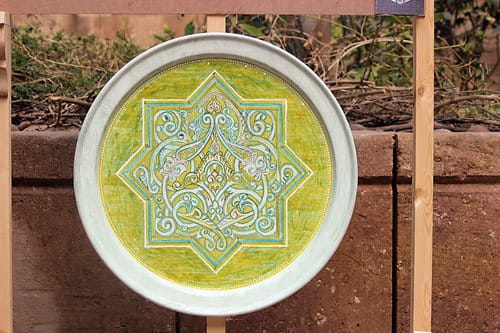

Made from both local and imported wood, the minbars range in height from five to eight meters. Every surface is ornamented with geometric and vegetal patterns set in finely carved and assembled panels featuring polygons, stars and interwoven strapwork, the dark wood often contrasting with delicate inlays using slivers of ivory, ebony, mother-of-pearl, camel bone and more, as well as calligraphy. While a few minbars of the era were made using polychrome marble for their patterns, the great majority are made of wood.

Watching Abu Zayd are Abdelrahman Aboulfadi, 29, and Alyaa Gamal, 27. They address him as “Usta Hasan” (Master Hasan) or, in less formal moments, “Am Hasan” (Uncle Hasan). Both are recent graduates from Cairo’s Jameel School of Traditional Arts, and they are now apprentices. It’s a relationship Abu Zayd finds familiar.

“I began watching my father and grandfather work on the gameya Arabic joinery technique as a child,” remarks Abu Zayd. “It can take a day or days just to make the drawings. Students must have patience and talent to persevere. You need to study for at least one year. Through this work we are continuing a tradition and preserving a legacy.”

“Minbars are like your crown jewel pieces of a mosque.”

—Omniya Abdel Barr

The minbar of the mosque of Ghanim al-Bahlawan is one of four that the Egyptian Heritage Rescue Foundation (EHRF) has helped to reconstruct as part of its Rescuing the Mamluk Minbars of Cairo Project, which launched in 2018 and concluded two years later. The minbar project was the brainchild of architect and Islamic art specialist Omniya Abdel Barr, Ph.D., who received support from EHRF, founded in 2013 to safeguard and promote Egyptian cultural heritage, to implement the project in partnership with Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. The project was funded by the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund in partnership with the Department of Culture Media and Sports. It documented 44 minbars, mostly in the Cairo area, 43 from the Mamluk period and one from the earlier Fatimid period. These are, Abdel Barr points out, living masterpieces that are still used for Friday sermons.

“Minbars are like your crown jewel pieces of a mosque, but they aren’t well documented,” says Abdel Barr. “You need to hire the best of the best to work on them because they are very intricate objects, very delicate, sophisticated and valuable.”

Eleven of the 44 minbars, she explains, received “first aid for emergency interventions” to repair damages due to centuries of wear and thefts of various pieces large and small. This work involved analyses of the contexts of damages, risk assessments of each minbar’s security against future thefts, and stabilization to preserve the affected minbars. Another 25 received “mitigation,” meaning action to prevent further damage such as removals of electrical wiring that could pose a risk of fire. Four minbars required full restorations. From documentation to restoration, most of the work was carried out by a team of 75 local volunteers. After the project ended in March 2020, Abdel Barr and her team worked for the next year under the title of the Mamluk Heritage Project, in which the team identified and documented other architectural elements in Cairo’s historic mosques that could be at risk of theft or damage.

Of the 44 minbars EHRF documented, 13 had been affected by theft, 25 required conservation, and four needed full restorations.

“Omniya is preserving this crucial historical moment in time for future generations, and that is fundamental to Arab world history,” says Porter.

Minbars are prominent elements of mosques worldwide, from simple ones to other masterworks, such as the 12th-century minbar of Salah al-Din, made in Aleppo, Syria, and moved to al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem following his conquest of the city in 1187 CE. In 1969 the minbar was destroyed by arson, and it took until 2007 to reconstruct it. Similarly, the 12th-century minbar of the Kutubiyah Mosque in Marrakesh, Morocco, has been estimated to comprise some 1.3 million wooden pieces. In Cairo, some of the most historically important minbars are those in the mosques of Sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay (1474 CE), al-Salih Tala’i (1160 CE) and Sultan al-Mu’ayyad Shaykh (1421 CE).

To assure better protection for several of the most valuable minbars, Abdel Barr says her team surrounded them with protective glass walls—like large museum exhibit cases—with locked doors that allowed the mosque’s imam (prayer leader) to continue to use them. “When we are not 100 percent sure if we can protect these precious elements, we add a layer of protection to the most vulnerable and beautiful minbars,” explains Abdel Barr.

The project faced formidable challenges. “We were working in very dark, dusty spaces—in not the best working conditions,” says Abdel Barr. “The team proceeded with love and passion. They felt that by removing the dust they were bringing an object back to its former glory.” After restoration and cleaning, they now glisten, radiant with their meticulous craftsmanship, much as they would have centuries ago.

Barr says she’s particularly fond of the minbar commissioned by Sultan Lajin in 1296 CE during his restorations of the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, which in Lajin’s time was already more than 400 years old. This is a minbar whose octagons, pentagons and connecting stars are each carved with intricate, interwoven vegetal designs in a decorative scheme that “shows the connection with previous minbars made by the Fatimids and the Ayyubids, especially the minbar of al-Aqsa,” explains Abdel Barr. “It shows the experience added in the craftsmanship and the development of the geometry.”

This is also the minbar from which panels are now housed in at least 12 international collections, including the V&A and the Louvre, the result of gradual stripping that took place in the late 19th century and even then raised conservation concerns.

“It took the Committee for the Conservation of the Monuments of Arab Art, which was established in 1881, 30 years to take the right decision to restore it a century ago, from 1913 to 1914,” she says. “This somehow gives me hope.”

While the minbar of Sultan Lajin illustrates how Cairo’s Mamluk minbars have been at risk of thefts for a long time—much like Egypt’s archeological sites—the problem spiked in the wake of the instability that followed the popular uprisings of 2011 in Cairo. Historic buildings, cultural institutions, archeological sites and museums all became targets of vandals and looters, many aiming to profit by sales. To Abdel Barr, it was as if sites of pride and identity were being wounded, disfigured.

As early as 2012, EHRF began documenting thefts in monuments and historic buildings in medieval Cairo, but often, lack of documentation made it difficult to prove whether a theft had taken place or if the minbar had been damaged over time due to mere neglect. This inspired EHRF’s work documenting the state of all the minbars in Egypt: a full set of architectural drawings and a photographic catalog for each one.

“Most of these attacks targeted minbars,” says Barr. Thirteen were affected by partial or total losses, she says. Attackers were lured not only by the meticulous woodwork but also by the wood’s relatively light weight and the small size of individual pieces that, if detached, could be slipped into a bag or even a pocket. This appears to have happened to the minbar at the Mosque of Al-Salih Tala’i, which lost panels on the lower corner of its right side. Though they have been replaced, the replicas lack the intricate ivory and bone decoration found elsewhere on the minbar. At the Mosque of Amir Qanibay Al-Rammah, built in 1503-1504 CE and overlooking the midan or plaza of Cairo’s Citadel, the minbar was stolen in its entirety.

Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities acknowledges the value of the minbars, but with the country’s tourism economy overwhelmingly pegged to Pharaonic-era sites and monuments, it does not allocate funds for this facet of Egypt’s vast heritage. In 2017, however, a Mamluk minbar was included in the displays at The National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, which opened that year. Its presence serves as a testament to the importance of the minbar craft, and of artisanal woodworking in general.

“Mamluk minbars represent a very important era of Islamic Egypt.... It is crucial that we preserve them for future generations.”

—Osama Talaat, Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities

“Mamluk minbars represent a very important era of Islamic Egypt,” says Osama Talaat, who heads the Islamic Antiquities Sector in the Supreme Council of Antiquities. “Minbars are one of the main components of mosques and ritual schools. During Friday prayers, the imam uses these minbars to speak to Muslims. Fortunately, we have over 200 mosques and ritual schools from the Mamluk era [in Egypt], and many of them still have the original minbars. It is crucial that we preserve them for future generations.”

This also means preventing the circulation and sale of illicitly obtained minbar pieces. “The looters of these minbars knew their value,” says Abdel Barr.

According to research by Maria Magdalena Gajewska, a doctoral student at Cambridge University’s Department of Middle Eastern Studies who is specializing in Islamic archeology and material culture, the prices of Mamluk minbar pieces have varied from under approximately $1,750 for a single panel to more than $1 million for a complete door.

She also found that over the two decades between 2000 and 2019, out of 53 lots of Mamluk wooden panels—comprising mostly minbar panels—auctioned at the leading houses of Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Bonhams, more than half had no disclosed provenance.

While it is illegal to remove antiquities from Egypt, prosecution is difficult. This led to another role for EHRF’s documentation: proving where a piece came from and when it was in situ or in its place of origin.

“The database allows us to document not just minbars but other objects, too, and it is shared with Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities,” explains Abdel Barr. “This is a very important resource that allows us to identify any object whenever it appears on the art market and to know its provenance or where it is coming from.”

“Omniya’s work is crucial in raising awareness of the issue, as well as the public’s appreciation of Mamluk art and in particular of minbar panels,” says Gajewska. “This is important especially in a country like Egypt, where the focus on ancient antiquities has meant that there is not much public outcry about the looting of medieval pieces, or indeed much awareness of their existence outside of specialized circles.”

The best way the market can assist in raising awareness of the importance of the minbars and their upkeep, stresses Gajewska, is by performing due diligence, erring on the side of caution when provenance is uncertain and consulting experts such as Abdel Barr and her team.

“EHRF is raising consciousness about the importance of the minbars, their heritage and the way they have been brought onto the market,” adds Porter.

Islamic art specialists agree that the goal is not to lessen the demand for Mamluk antiquities—in fact, Abdel Barr and EHRF, by reviving and documenting Egypt’s minbars, may be helping raise their market value and prestige—but to ensure that antiquities are acquired legally.

As Aboulfadi and Gamal watch Abu Zayd’s every move, they are using their skills not only to help restore Mamluk architecture, but also to create contemporary design objects with traditional techniques and motifs. In 2020 Abdel Barr and her colleagues set up a collaboration with more than a dozen young Egyptian artisans called The Design Hub. From tea boxes to tiles, clothing, dishware, furniture and more, their creations reverberate with the same beauty and energy found on Mamluk heritage items.

“I love sculpture and geometry, and I found my true passion working with wood, especially joinery technique, as I found it is like problem-solving using logic and adding details to any piece through carving and inlay,” explains Gamal.

For her graduation project last year, Gamal created a prototype for a joinery panel, and she documented the steps to its creation, including trials and errors, as a kind of living guidebook for future students. Now she tutors students in joinery at the Jameel center while also apprenticing with Abu Zayd.

“I love analyzing all of his samples, drawing them again and making some of them,” muses Gamal, who this year traveled to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, to teach a wood workshop there at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts.

For Abdel Barr, there remain more minbars she would like to see restored, such as the minbar of Sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay in his 1474 CE funerary complex in Cairo’s northern cemetery. But it is on hold until Abdel Barr secures further funding and arranges the artisans.

“We have realized the lack of expertise in the field of woodwork and are trying to think of how we can create a new generation of makers who can assist us with the conservation,” says Abdel Barr. “There are other minbars that are awaiting help.”

About the Author

Rebecca Anne Proctor

Rebecca Anne Proctor is an independent journalist, editor and broadcaster based between Dubai and Rome. She is a former editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar Art and Harper’s Bazaar Interiors.

Richard Doughty

Richard Doughty is editor of AramcoWorld. He holds a master’s degree in photojournalism from the University of Missouri.

You may also be interested in...

The Bridge of Meanings

History

Arts

There is no truer symbol of Mostar, Bosnia-Herzegovina, than its Old Bridge. The magnificent icon of Balkan Islamic architecture was destroyed during the 1992–’95 war—but not for long. Like the multicultural workforce that produced the original hundreds of years earlier, a broad team of architects, engineers and others came together immediately to plan its reconstruction. This summer marked the 20th anniversary of the bridge’s reopening.

AramcoWorld Explores Connections Through Architecture

Arts

Since its beginnings 75 years ago, AramcoWorld’s editors have viewed architecture as an essential lens on history and a crucible for cultural connections. Early stories, in particular, added human context to a discipline that often focused on the form of buildings with little regard for the people who used them. In Part 4 of our series marking our 75th anniversary in 2024, we look at the ways these stories encapsulate architecture in the evolution of world history.

Brickwork in the Land of Palms

Arts

Along the northern edge of the Sahara, in the part of Tunisia called Bled el-Djerid—Land of the Palms—the regular pruning of vast date-palm orchards literally fuels a centuries-old brickmaking industry, and local bricklayers have taken the kiln-fired masonry to heights of artistry. Throughout the city of Tozeur and the nearby town of Nefta, bricks set in patterns decorate facades, windows, doors and arches with motifs from desert life, textiles and other traditions. The results not only dance with the changing angles of the sun, but also create just enough shade to help cool the buildings behind them.